Decarbonise Buildings - regulate, incentivise, facilitate

CAT Blog

The global carbon budget to keep warming below 1.5°C is rapidly diminishing. Despite this fact, and the need for all sectors to decarbonise, buildings sector emissions have remained stubbornly consistent -- they make up roughly a fifth of total global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. In our latest report, we examine why this is and what action governments need to take to initiate transformative change.

A Paris Agreement-aligned building sector would mean that all new buildings are zero carbon and retrofitting rates of existing buildings reach 2.5-3.5% per year. Both the energy and emissions intensity of all buildings are reduced rapidly in the coming decades, with emissions intensity reaching zero around 2050.

Heating buildings currently relies heavily on the direct use of fossil fuels. Reliance on gas for heating is majorly impacting household budgets through rapidly rising gas prices, especially in Europe and Asia. Major improvements to energy efficiency in buildings, electrification of heating technologies, and the installation of on-site renewables are the long-term solutions for protecting households from such price fluctuations.

Elsewhere in the world, maintaining cool temperatures is much more important, and demand is increasing due to both a warming climate and the ability of more people to afford access to cooling. Increased access to cooling is a positive trend, but at the moment it is commonly achieved by installations of low-efficiency, single unit air conditioners that consume high amounts of electricity, rely on potent synthetic greenhouse gases as cooling agents, and exacerbate the urban heat island effect.

The technologies to decarbonise buildings are well understood and widely available. Improvements to the building envelope, including insulation, shading, and ventilation, have clear long-term energy and cost savings.

- Heat pumps are highly efficient and now able to work in some of the coldest climates.

- The latest district heating and cooling technology works at lower temperatures and is compatible with renewable energy supply.

- Natural refrigerants provide an affordable, and less climate impactful alternative to fluorinated refrigerants.

- The cost of rooftop solar installations and home batteries have dramatically decreased, making heat pump technologies more financially attractive and further improving their sustainability.

The challenge is in the actual implementation of all the existing technologies.

The buildings sector is diverse and complex. Buildings come in all shapes and sizes, are used as residences or for commercial operations, may be built new or need to be retrofitted, and requirements for achieving zero carbon vary across climate zones. Adding to that, each construction or reconstruction involves a multitude of actors, including owners, property developers, banks, tenants, contractors, and architects.

The buildings sector has shown it will not ‘tip’ with just a few initiatives. As a complex challenge, reducing emissions in the buildings sector requires a comprehensive and multi-faceted strategy.

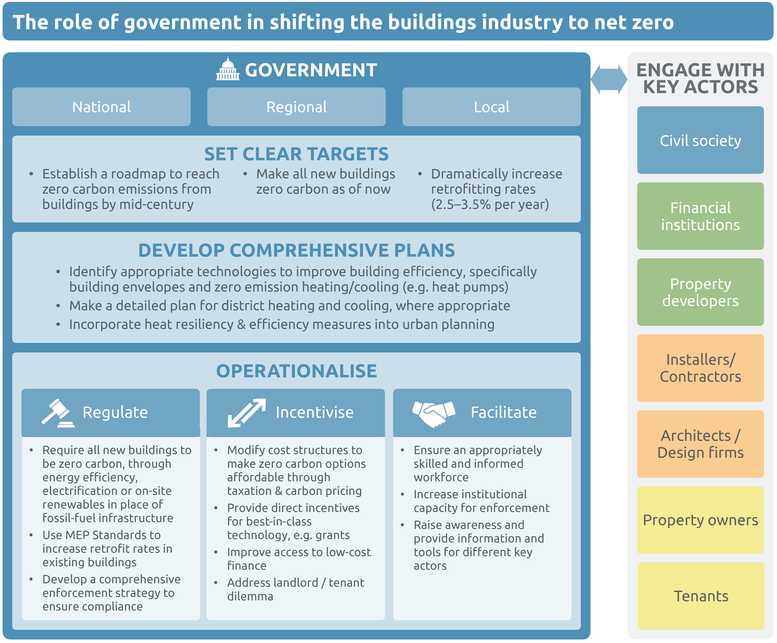

Governments are in a unique position to effect change, as they can influence many actors and set the overall direction of the economy towards decarbonisation. Three major steps are required from national, regional, and local governments:

- Set out a clear vision and underlying climate targets for the buildings sector.

- Develop a detailed strategy for decarbonisation at the national, regional, or local level.

- Operationalise the plan with a broad set of policies that regulate, facilitate, and incentivise the transition.

There is not yet an example of a country that has successfully decarbonised its buildings sector, but there are good examples of cities, regions and countries that have adopted a more comprehensive approach and are starting out in a good direction, or that have made good progress. Here are just three examples and you can find many others in our report.

- Grenada identified emissions from air-conditioning as a major contributor to national total emissions. The government has developed a National Cooling Action Plan that incorporates stringent energy efficiency building codes, appliance efficiency standards for cooling appliances, and a shift to natural refrigerants in place of HFCs. The new regulations are supported by plans for improved communication, capacity building, sustainable public procurement, and developing access to finance.

- Ithaca, New York, has approved an Energy Efficiency Retrofitting and Thermal Load Electrification Program with the goal of decarbonising all 6,000 buildings in the city by 2030. A particularly interesting component is how the program addresses the key challenge of financial risk in taking on loans to perform retrofits.

The city plans to use a New York State government-backed loan loss reserve to guarantee private loans and secure sufficient funding for the program. At the same time, the city is seeking to provide further support in terms of awareness, engagement and capacity to ensure success of the program.

- Sweden has managed to reduce its emissions from the building sector by around 2/3 since 1990 through a series of reinforcing policies. It slowly ramped up a carbon price, supported local heat pumps manufacturing, and the electricity grid has a low carbon intensity. In addition, the government took action to incentivise landlords to retrofit rental properties. Together, these policies have led to massive uptake of heat pumps and district heating to keep buildings warm.

Sweden and others have shown what can be done. Other governments can learn from their example and need to utilise a broad portfolio of policies to effect more change over a shorter timeframe.

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter