Targets

Target Overview

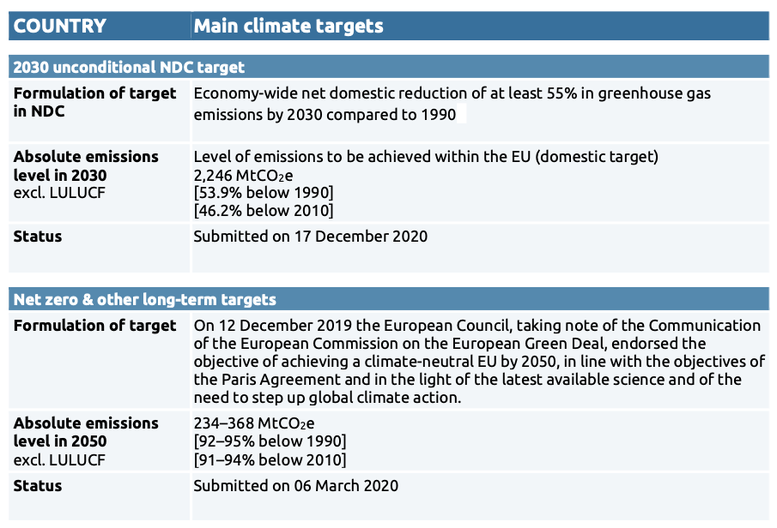

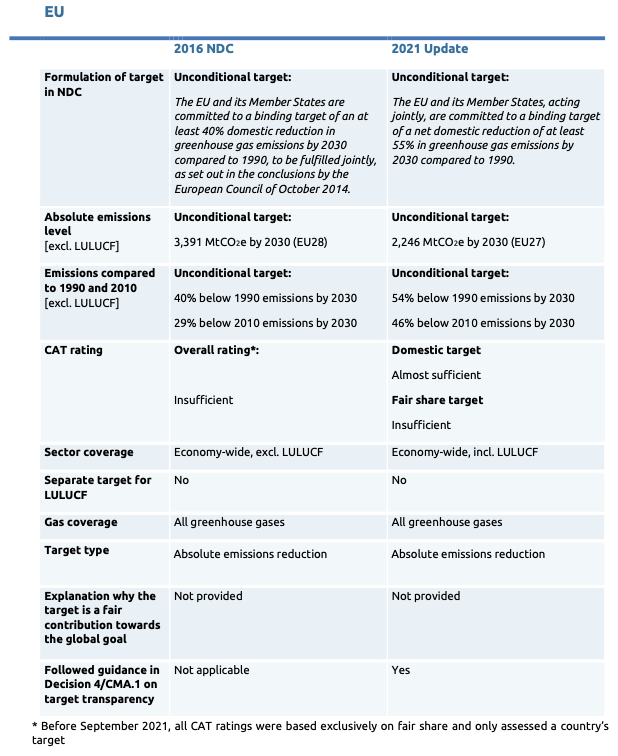

In December 2020, the EU submitted an updated version of its NDC to the UNFCCC (Germany and the European Commission, 2020b). The updated NDC provides a strengthened 2030 emissions reduction target of “at least 55%” compared to the previous NDC’s target of “at least 40%”. However, the new target includes emissions from the LULUCF sector, which was not the case for the previous NDC, making it more difficult to directly compare them. Due to the United Kingdom having left the EU on 31 January 2020, the updated NDC applies only to the current 27 Member States. The NDC clarifies that emissions from outgoing flights that start in the EU are included in the goal, however this information “is subject to revision in light of the enhanced target”.

The “Fit for 55” package presented by the Commission in July 2021 provides more detail concerning measures for international aviation and maritime. According to the Commission’s modelling reflecting the “Fit for 55” package, the EU’s emissions would amount to 2.2 GtCO2e in 2030, excluding LULUCF and international aviation and maritime transport (European Commission, 2021e). This is almost 54% below emissions in 1990. The renewable energy and energy efficiency targets proposed by the Commission in its REPowerEU Plan would result in emissions between 2,040 and 2,090 MtCO2e, or between 57% and 58% below emissions in 1990.

CAT rating of targets

NDC description

In December 2020, the EU submitted an updated version of its NDC to the UNFCCC (Germany and the European Commission, 2020b). The updated NDC provides a strengthened 2030 emissions reduction target of “at least 55%” compared to the previous NDC’s target of “at least 40%”. However, the new target includes emissions from the LULUCF sector, which was not the case for the previous NDC, making it more difficult to directly compare them. Due to the United Kingdom having left the EU on 31 January 2020, the updated NDC applies only to the current 27 Member States. The NDC clarifies that emissions from outgoing flights that start in the EU are included in the goal, however this information “is subject to revision in light of the enhanced target”.

The European Climate Law adopted in June 2021 clarified some aspects around the new NDC target (European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, 2021). The law provides an upper limit of 225 MtCO2e for the LULUCF emissions sink that can be used to meet the NDC.

The “Fit for 55” package presented by the Commission in July 2021 provides more detail concerning measures for international aviation and maritime: intra-EU aviation will continue to be included in the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS), but will be deprived of free emissions allowances. Extra-EU aviation will be covered by the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA), although this scheme has serious failings. All emissions from intra-EU maritime transport and half of the emissions from extra-EU maritime transport will be included in the EU ETS (European Commission, 2021g).

According to the Commission’s modelling reflecting the “Fit for 55” package, the EU’s emissions would amount to 2.2 GtCO2e in 2030, excluding LULUCF and international aviation and maritime transport1 (European Commission, 2021e). This is almost 54% below emissions in 1990. The renewable energy and energy efficiency targets proposed by the Commission in its REPowerEU Plan would result in emissions between 2,040 and 2,090 MtCO2e, or between 57% and 58% below emissions in 1990.

In addition, the Commission’s proposal for accounting emissions from LULUCF obliges Member States to increase the emissions sink to a least 310 MtCO2e—even though only 225 MtCO2e can be accounted towards this goal (European Commission, 2021k). If adopted, this would create an additional sink of 85 MtCO2e, which is not considered in this assessment. This would amount to emissions reduction by between 60 and 62% below 1990 levels by 2030.

The CAT rates NDC targets against what a country should be doing within its own borders as well as what a fair contribution to achieving the Paris Agreement’s long-term temperature goal would be. For what we call the ‘fair share target’, we consider both a country’s domestic emission reductions and any emissions it supports abroad through the use of market mechanisms or other ways of support, as relevant.

The EU does not intend to use market mechanisms and will achieve its NDC target through to domestic action alone. We rate its NDC target against both domestic and fairness metrics.

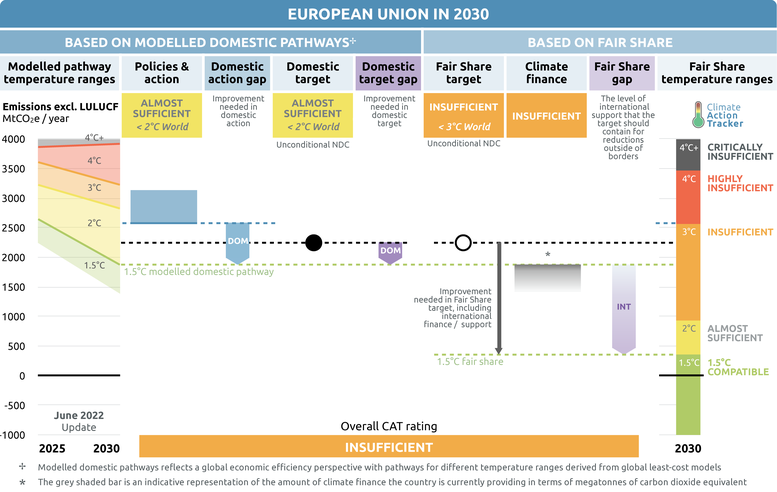

The CAT rates the EU’s NDC target (“domestic target”) as “Almost sufficient” when compared to modelled domestic pathways and “Insufficient” when compared to its fair share emissions allocation (“fair share target”).

1 | The numbers provided in the scenario use Global Warming Potential from IPCC AR5. For the sake of comparability with other countries assessed by the Climate Action Tracker the number 2.262 MtCO2e is translated to AR4 resulting in 2.246 MtCO2e.

The EU’s new domestic target of reducing emissions by “at least 55%” (including LULUCF) is a step in the right direction, especially as the EU has also proposed measures to achieve this goal. Due to the limit on the amount of emissions in the LULUCF sector that can be accounted for in the target, it translates to emissions reduction by “at least 52.9%” (excluding LULUCF).

The target also explicitly includes international aviation. Excluding it for the sake of comparability with other countries assessed by the Climate Action Tracker increases the target to 53.9%. In addition, while the NDC only mentioned domestic navigation, the recent proposal of the European Commission would also cover emissions from intra-EU maritime transports and half of the extra-EU maritime transport in the new Emissions Trading Scheme.

The new target is rated as “Almost sufficient”. The “Almost sufficient” rating indicates that the EU target in 2030 is not yet consistent with the 1.5°C temperature limit but could be, with moderate improvements. If all countries were to follow the EU’s approach, warming could be held below—but not well below—2°C.

When measured against a fair-share emissions allocation, we rate the EU’s emissions reduction target as “Insufficient”. The “Insufficient” rating indicates that the EU’s fair share target in 2030 needs substantial improvement to be consistent with the 1.5°C temperature limit. Some of these improvements should be made to the domestic emissions target itself, others could come in the form of additional support for emissions reductions achieved in developing countries in the form of finance. If all countries were to follow the EU’s approach, warming would reach up to 3°C.

The EU’s international climate finance is rated “Insufficient” (see below) and is not enough to improve the EU’s fair share rating.

The EU’s international public climate finance contributions are higher than those of most other countries but are still rated “Insufficient.” The EU has committed to increasing its climate finance, but contributions to date have been low compared to its fair share. To improve its rating, the EU needs to ramp up the level of its international climate finance contributions post-2020 and accelerate the phase-out of fossil fuel finance abroad.

In 2019, the EU and its Member States provided EUR 23.2 bn to developing countries (Germany and the European Commission, 2020a). Even though the overall level of climate finance reported by the EU is higher than most countries, contributions fall short of its fair share contribution to the USD 100 bn goal. This is partially due to the EU’s strict fair share requirements. Also, the CAT does not consider all country-reported contributions as climate finance. We provide a range for each country that covers different interpretations of climate finance to account for concessionality and finance instrument type, for example (see methods). The amount the CAT compares to the USD 100 bn benchmark is often lower than the one reported by countries.

The contribution marks a 6.9% increase compared to 2018 and includes EUR 2.5 bn from the EU budget and the European Development Fund as well as EUR 3.18 bn from the European Investment Bank. Relative to their gross national income, Luxembourg, Germany and France lead the list of highest shares in contributions (Dejgaard & Appelt, 2018). Due to the high fair share requirements, reported contributions fall short of the EU’s fair share contribution to the USD 100 bn goal, despite past increases.

To incorporate finance flows into the plans to achieve long-term climate goals, in June 2020 the EU adopted the Taxonomy Regulation establishing framework for sustainable investment (The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, 2020). On the basis of this Taxonomy Regulation, a year later the Commission adopted a Delegated Regulation that listed detailed criteria for assessing a certain activity as either contributing substantially to climate change mitigation, or causing no significant harm to any of the EU’s environmental goals (European Commission, 2021a). The Delegated Regulation also defines which activities can be defined as causing significant environmental harm. The EU’s Taxonomy Regulation is mostly designed to determine internal financial flows, but it could also be applied to assessing the sustainability of EU’s investment abroad.

In February 2022, European Commission published a complementary climate delegated act to its Taxonomy Regulation (European Commission, 2022a). The act stated that energy generation from fossil gas and nuclear should be classified as transition activities: activities that cannot yet be replaced by low carbon alternatives but do contribute to emissions reduction. For this purpose, electricity generation from these sources need to fulfil several criteria. For fossil gas power plants, the life-cycle emissions should be below 100gCO2e/kWh.

Fossil gas power plants permitted before 2030 can emit up to 270gCO2e/kWh but only if renewables are not available at sufficient scale. Finally, fossil gas power plants which don’t emit more than 550 kgCO2e per kilowatt of installed capacity classify as transition activity, but only if they replace a facility using solid or liquid fuel, and switch fully to renewable or low carbon gases by 2035. Despite the criteria, allowing for any investments in fossil gas infrastructure to be referred to as compatible with the EU’s climate ambition is surprising, especially at the time when the negative consequences of EU’s dependency on fossil fuel imports not only for the climate but also for its economy and security is becoming so obvious.

In 2019, the European Investment Bank adopted its climate strategy to phase out fossil finance by 2021 (EIB, 2019). EU foreign ministers also called for the ending of export guarantees for fossil fuel projects overseas to promote a global fossil fuel phase-out (Simon & Taylor, 2021). Yet some Member States still support fossil fuel internationally, such as Germany in providing public guarantees for gas turbines (Euler Hermes Aktiengesellschaft, 2020) and the Czech Republic by means of state-own export credit agency EGAP (Norlen, 2017). In July 2021, the European Council agreed that EU public funding will be used for two new pipelines exclusively for the transport of natural gas, including the EastMed pipeline that would transport fossil gas from offshore Israel to Cyprus, Greece (Council of the European Union, 2021b).

The EU remains committed through 2025 to the USD 100 bn collective goal of climate finance for developing countries, but the USD 100 bn goal itself is insufficient for the post-2020 period. The European Commission also proposed to increase its total external contributions by 70% to at least EUR 4.2 bn per year (2021–2027) (Eckstein, Argueta, Ryfisch, & Hübschen, 2021). However, this increase alone is insufficient to improve the EU’s CAT finance rating, which requires a halt in fossil fuel finance overseas as well as additional finance mobilisation.

Further information on how the CAT rates countries (against modelled pathways and fair share) can be found here.

NDC Updates

On 11 December 2020, the heads of EU Member States agreed on a stronger 2030 domestic emissions target of “at least 55%” net reduction below 1990 levels. This goal was submitted to the UNFCCC on 18 December as part of the EU’s NDC. This target is an improvement of the EU’s previous target of “at least 40%”. Changes in the treatment of the land sector slightly weaken this target compared to its predecessor, resulting in an emissions reduction of 52.8% below 1990 levels excluding LULUCF. However, the inclusion of aviation and maritime emissions, strengthen it to 54% below 1990 levels.

While this stronger 2030 target is a step in the right direction, it is still not enough to make the EU compatible with the 1.5˚C goal. Domestic emissions reductions of at least 62% are needed to make the EU’s effort compatible with 1.5˚C. Stating “at least” indicates that the EU can go beyond the 55% benchmark by adopting more ambitious policy measures.

The measures proposed in the framework of the July 2021 “Fit for 55%” package, especially increasing the share of renewable energy to 40% in final energy consumption and decreasing final energy consumption to 787 Mtoe in 2030, would result in a 55% emissions reduction below 1990 levels. The goals of increasing the share of renewable to 45% and reducing final energy consumption to 750 Mtoe in 2030 proposed by the Commission in its REPowerEU Plan, would result in emissions reduction by around 58%.

Analysis of earlier NDC developments:

Net zero and other long-term target(s)

In April 2021, the European Union came to an agreement on its Climate Law, which sets into law the objective of collectively achieving “climate neutrality by 2050.” The objective of achieving climate neutrality by 2050, as agreed in the European Council’s conclusions from December 2019, has been included in the EU’s LTS.

The EU’s climate neutrality - or, essentially, net zero - goal performs moderately in terms of its architecture, transparency and scope, with a regular review and assessment process, a provision for the EU to set an intermediate target in 2040 following the Paris Agreement’s Global Stocktake, an exclusion of reductions or removals achieved outside of its territory, and clear analysis underpinning the target. At present, a clear separation of the contributions from emissions reductions versus removals is missing, although this is an element that is required of the forthcoming 2040 target.

There is room for improvement in the goal’s scope, as the Climate Law currently does not clearly state that international aviation and maritime transport emissions are included, and an explanation of why net zero by 2050 constitutes a fair contribution is lacking.

For the full analysis click here.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter