Policies & action

Germany’s current policies are “Almost sufficient” when compared to modelled domestic pathways. With implemented policies, Germany’s 2030 target is at risk and the government will not achieve its long-term targets.

The “Almost sufficient” rating indicates that Germany’s climate policies and action in 2030 are not yet consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C but could be, with moderate improvements. If all countries were to follow Germany’s approach, warming could be held at—but not well below—2°C.

Further information on how the CAT rates countries (against modelled pathways and fair share) can be found here.

Policy overview

The newly-elected German government’s climate agenda, as outlined in its coalition agreement, will likely undermine existing emissions reductions efforts rather than reinforce them. The previous government, which had been in power since 2021, significantly accelerated climate policy implementation. Nevertheless, the previous government’s policies and actions were still insufficient to reach the country's climate targets, as enshrined in law in the Climate Change Act. Given that the new government is weakening existing policies across all sectors, Germany’s climate targets will likely be even further out of reach.

The new government is explicitly compromising existing emissions reductions efforts in the energy, transport, and buildings sectors. The new government plans to double the previous government’s new gas-fired power capacity from 10 GW to 20 GW by 2030 and remove the requirement to build new plants to be hydrogen-ready. In doing so, the government seriously risks locking in additional emissions from the sector and jeopardises Germany’s 2045 climate neutrality target.

The coalition contract outlines measures to support the short-term interests of German auto manufacturers, instead of proposing policies that would reinforce the industry’s long-term competitiveness, while reducing its emissions. As markets across the world shift towards EVs, the new government’s transport policy package threatens to put German automakers at a competitive disadvantage.

In the buildings sector, the new government plans to undo the previous government’s flagship “Building Energy Act”, which included a de facto ban of new oil and gas boilers from 2026 to 2028.

Further challenging emissions reductions efforts is that German forests are no longer an emissions sink but are now a net source. The forest sink capacity was a key component of the government’s plan for reaching climate neutrality by 2045.

The new government’s restructuring of federal ministries is also likely to complicate federal climate action. The government has split the responsibility for climate and energy policy across different ministries, even though these policy areas overlap significantly. Domestic and international climate policy now strictly falls under the environment ministry, while the economics ministry remains responsible for energy.

The new government agreed to mobilise EUR 500bn in special funds ("Sondervermögen") for infrastructure and climate over the next 12 years. EUR 100 bn is designated for investments in reducing greenhouse gases. It remains unclear towards which sectors and which emissions reductions efforts the funds will be channelled. However, the real opportunity lies with the remaining EUR 400bn, which the government could use to further support the transition to climate neutrality or at least not hinder the transition. This however would require significant political will and clear spending rules.

We conclude from our review of the Federal Environment Ministry’s (UBA) emissions inventory (UBA, 2025b) and its emissions projections from March 2025 (UBA, 2025c), that the 2030 target is even more difficult to achieve in comparison to our assessment in 2024. Nevertheless, the UBA claims that the cumulative emissions target from 2021 to 2030 will be achieved, but only because of temporarily lower emissions levels during the COVID-19 pandemic. Germany's emissions level in 2030 is projected to be above the 2030 target.

The UBA's projections rely on optimistic assumptions. The government assumes significant increases in the share of renewable energy generation, electric vehicles (EV) sales, and CO2 certificate prices. At the same time, the UBA forecasts that output from emissions-intensive industry remains low.

However, growth in wind energy and EV sales has slowed in recent years, while CO2 prices remain substantially lower than projected. Combined with the new government’s weakening of existing climate policies and actions, it will be increasingly challenging for Germany to achieve its emissions reductions target for 2030.

It is of major concern that the new government proposes to use international carbon credits through the Paris Agreement's Article 6 to meet its national emissions reductions target. Relying on international carbon credits from outside of the EU would be against current German and EU law and a major step backwards, weakening action and ambition (see CAT’s recent output on Article 6).

The previous government weakened the Climate Change Act in 2024. It did so by replacing the compliance mechanism for binding sectoral emissions reductions targets with the ability for sectors to compensate for each other, as long as the overall target is met. Amending the compliance mechanism conceals the fact that the transport and buildings sectors will exceed their 2030 targets. It will be almost impossible for the transport sector to catch up after 2030 unless drastic and disruptive measures are taken. Significant compensation from the other sectors will also not possible after 2030, as it will become increasingly difficult for sectors to reduce any additional tonnes of CO2.

Power

According to the targets anchored in the Climate Change Act, the energy sector (electricity and heat supply) will have to limit its GHG emissions to 108 MtCO2e by 2030, a reduction of 62% below 1990 levels.

In 2024, total emissions from the energy supply sector stood at 185 MtCO2e, a decrease of 18 MtCO2e compared to the previous year (UBA, 2025c). While this marks a continued decline, the reduction is less than in the previous year.

Still, the energy sector is responsible for around 77% of the total emissions reduction in 2024, underlining the dominant role in Germany’s mitigation process. As in the previous year, renewable energy once again covered more than half of gross electricity consumption in 2024 (Expertenrat für Klimafragen, 2025).

Despite these positive developments, the sluggish expansion of wind energy and the extensive new investments in fossil gas infrastructure pose a risk to Germany's ability to achieve its longer-term targets for 2030 and 2045. The new government’s strategy to install up to 20 GW of new fossil gas-fired power capacity by 2030—twice the amount planned under the previous coalition—marks a significant escalation and risks further locking in fossil infrastructure. Notably, these new plants are not required to be hydrogen-ready, raising concerns about long-term compatibility with Germany’s climate neutrality goal.

Germany’s coal phase-out remains a critical component of its energy transition, but current plans continue to fall short of global climate benchmarks. The previous government had signalled a potential coal exit by 2030, particularly through the 2022 agreement between RWE and the state of North Rhine-Westphalia. However, it ultimately stepped back from this ambition at the national level and instead expressed hope that coal would become economically unviable after 2030 due to rising carbon prices under the EU ETS. The new coalition government follows this retreat and no longer even refers to the 2030 phase-out as an ideal scenario. Instead, it reaffirms the legally binding exit date of 2038. A slow and gradual coal phase-out by 2038 puts pressure on global emissions budgets, which require a coal phase-out by 2030 (Climate Action Tracker, 2023).

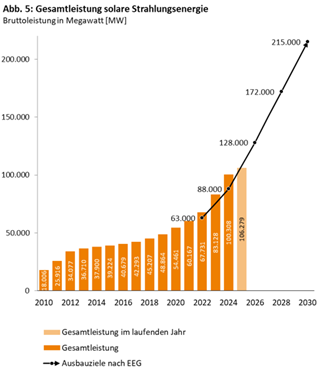

With currently adopted policies, Germany could exceed its 2030 power sector target by 15 MtCO2e according to the 2025 UBA report. However, the UBA projections assume renewable capacity will grow according to the government’s early 2022 plans. The UBA expects 78% of the 80% renewable share to be reached by 2030 (UBA, 2025c). While solar is largely on track, onshore wind has again fallen behind in 2024.

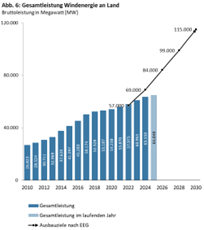

The Expert Council on Climate Issues (ERK) highlights key uncertainties in these projections. It considers the assumed expansion path for onshore wind (104 GW by 2030) as ambitious, exceeding other scenarios (e.g. EWI, IEA) by several gigawatts. Offshore wind projections (27 GW) are seen as plausible, while solar PV (215 GW) may be a little underestimated. Overall, the expansion paths may be slightly overstated, which could lead to an underestimation of emissions (Expertenrat für Klimafragen, 2025). assumes that the renewable electric capacity increases as in the government's original plans from early 2022. For solar energy, this has been the case. For wind energy, implementation has once again fallen behind in 2023.

The price for CO2 emission allowances in the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) fell steadily from a level of around EUR 100/tCO2 in February 2023 to a low of EUR 52/tCO2 in early 2024. Throughout 2024, prices remained at relatively low levels, before rising again in early 2025 to currently range between EUR 60 and EUR 83/tCO2 (Ember, 2025). With the reform of the EU ETS, it was expected that these prices would increase further. Higher prices make coal very unattractive compared to renewables.

Renewables

Accelerating renewable energy expansion is a priority of the German government and has been approached through a comprehensive set of reforms, increased capacity targets and legislative measures aimed at removing deployment barriers. Germany revised the Renewable Energy Sources Act (EEG) and the Offshore Wind Energy Act (WindSeeG) in 2023, establishing that renewable energy installations are in the overriding public interest, allowing them to be prioritised over competing concerns. The reforms also strengthens support for rooftop solar PV, participatory energy models for citizens, storage, and the shift of biogas toward flexible electricity generation (BMWK, 2023f, 2023d).

Electricity generation from renewables stands at 60% January to June 2025 (Fraunhofer ISE, 2025b).

(BMWK, 2022) With the EEG 2023, the German government has set a binding target of 80% renewable energy of gross electricity consumption by 2030, replacing earlier, less ambitious planning (65% by 2030) (BMWK, 2023g). This increased ambition is accompanied by expectations of a significant increase in overall electricity demand, as electrification progresses across the transport, buildings and industry sectors. This goal is not yet fully aligned with the Paris Agreement but is getting close: studies suggest the share of renewable electricity in total generation needs to reach 86-89% by 2030 to be compatible with a 1.5°C pathway (Climate Action Tracker, 2023).

The government is aiming for a cumulative installed renewable electricity capacity of 360 GW by 2030, including 215 GW solar PV 115 GW onshore wind and 30 GW offshore wind (Federal Ministry of Economics and Climate Protection, 2022), more than twice the 169 GW installed as of early 2025 (Fraunhofer ISE, 2025a). In support of this, the EEG 2023 raised annual expansion targets and tender volumes, while the Photovoltaics Strategy 2023 outlines further enabling measures to speed up deployment (BMWK, 2023e).

Solar capacity additions are ramping up at record levels, with the addition of 15 GW in 2024 alone, reflecting the impact of supportive government policies. Notably, this surge has allowed Germany to build a temporary buffer by overachieving its annual targets in recent years.

However, the pace appears to be slowing in 2025: if the trend of the first six months continues, Germany is expected to add only around 10 GW of new solar capacity in 2025 (Fraunhofer ISE, 2024). While this still draws on the buffer created earlier, it falls well short of the government’s goal to expand solar capacity by 22 GW annually by 2028 (Wirth, 2023).(IEA, 2024) Sustaining progress toward this target will require a renewed acceleration in renewables deployment in the coming years to avoid depleting the current lead.

The government’s target for onshore wind under the EEG 2023 was to reach 69 GW of installed capacity by 2024, but missed this target by around 5 GW. Onshore wind capacity expansion also remains below its all-time high of 5.5 GW, achieved in 2017. In 2024, only 3.3 GW of new capacity were added (Deutsche WindGuard GmbH, 2025), just over half of the 6 GW that had been planned for the year (BMWK, 2022). The shortfall is due to earlier low auction volumes and ongoing delays in grid connections, component deliveries, and transport infrastructure.

Because expansion between 2022 and 2024 fell short of expectations, to meet the government's targets, the annual pace now needs to increase to 8.5 GW through 2030. This would require building out onshore wind nearly 2.5 times faster than in 2024. To reach the upcoming short-term target of 84 GW by 2026, annual additions of around 10 GW would be necessary in both 2025 and 2026. However, based on the pace observed in the first half of 2025, only about 3 GW appear achievable this year (Fraunhofer ISE, 2025a).

On a more positive note, 2024 saw a record level of permitting activity. Authorities approved around 2,400 new turbines with a total capacity of over 14 GW, an 85 percent increase compared to the previous year (Deutsche WindGuard GmbH, 2025). This surge suggests that recent acceleration measures, including the EU Emergency Regulation and the legal recognition of wind power as being of overriding public interest, are beginning to show results. If this momentum in permitting can be matched by faster project implementation, it could pave the way for a more robust expansion of onshore wind in the years ahead.

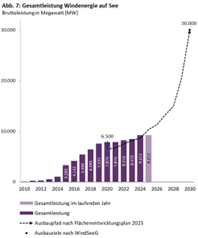

Germany's offshore wind capacity currently stands at just 9 GW (Fraunhofer ISE, 2025a), well behind the 30 GW target set for 2030. The Area Development Plans published in 2023 and 2025 are important steps toward closing this gap, as they define clear timelines and designated areas for offshore wind expansion (BSH, 2023, 2025). While the political framework is moving in the right direction and planning processes are accelerating, scaling up deployment to the required level remains a significant challenge.

Germany’s National Hydrogen Strategy (German Government, 2020b), originally adopted under the 2017–2021 government, committed EUR 11 billion to support hydrogen-related projects (BMWK, 2023a). The subsequent government (2021–2025) updated the strategy in June 2023, doubling the electrolyser capacity target from 5 GW to 10 GW by 2030 (BMWK, 2023c), and emphasised the role of hydrogen in industrial decarbonisation, as reflected in the 2021 coalition agreement.

The first auction of “Carbon Contracts for Difference” (CCfDs), through which the additional costs of companies compared to conventional production are compensated, was launched in March 2024 (BMWK, 2024). The strategy also supports projects to import green hydrogen from countries such as Australia, Morocco, Brazil, and South Africa, and includes plans to develop an auction model for green hydrogen deployment. However, importing green hydrogen over long distances raises questions about the sustainability of related transport emissions. Additionally, the strategy foresees the temporary use of hydrogen from fossil gas, which is not "green" hydrogen.

The new coalition government formed in 2025 reaffirmed its commitment to a rapid scale-up of the hydrogen economy, aiming for a long-term transition to climate-neutral hydrogen from domestic and imported renewable sources. The coalition agreement emphasises pragmatic regulation, expanded infrastructure for imports, and the development of a nationwide hydrogen core network.

Coal

The share of coal in Germany's electricity system has been almost halved over the last ten years, but still stands at 24% for January to June 2025, of which more than two-thirds are from lignite, the most emissions-intense form of coal (Fraunhofer ISE, 2025b). Roughly one quarter of CO2 emissions from coal-fired electricity generation in Europe are from Germany (IEA, 2025a).

In July 2020, the former government adopted a coal exit law stipulating the last coal-fired power plant will be closed by 2038. The compromise was found only by compensating the affected regions (with EUR 40bn) and the affected companies operating the coal-fired power plants (with an additional EUR 4.35bn) (Agora Energiewende, 2019; Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie, 2019).

In November 2020, the European Commission approved its proposed competitive coal phase-out tender mechanism under the coal exit law (European Commission, 2021). In the first auction rounds between September 2020 and March 2022, the Federal Network Agency awarded bids for a combined capacity of around 9.7 GW (Bundesnetzagentur, 2022).

The operators received up to EUR 165,000 for each MW of installed capacity to be phased out by the end of 2022 at the latest and, in 2021, a total of 5.8 GW coal capacity was retired (Bundesnetzagentur, 2021, 2022; Global Energy Monitor et al., 2022).

A total of 16 lignite and hard coal-fired power plants in Germany were shut down by June 2025. This included seven lignite-fired power plant units with a capacity of around 3.1 GW, which the German government had originally planned to shut down earlier. Due to energy-saving measures for natural gas during the energy crisis, the shutdown date for two of these units was postponed and the remaining five units were taken out of security standby (MDR, 2024; Zeit, 2024).

According to the new 2025 coalition agreement, the government continues to pursue a coal phase-out by 2038. The coalition agreement now ties the timeline for decommissioning coal plants — or placing them in reserve — to the pace of building new controllable gas-fired power plants, effectively making climate ambition conditional on fossil fuel infrastructure expansion.

The new government has entirely dropped the previously stated ambition of phasing out coal “ideally” by 2030. A legally required federal evaluation of whether a 2030 phase-out would be feasible has still not been carried out. While the energy company RWE and the state of North Rhine-Westphalia maintain their bilateral agreement to phase out coal by 2030, the eastern German states have reaffirmed their opposition to ending coal mining and coal-fired power generation in their regions by 2038.

The attempt by the previous government to bring forward the coal phase-out may have paradoxically led to increased greenhouse gas emissions: in early 2022, RWE and the state government of North Rhine-Westphalia agreed to advance the coal phase-out from 2038 to 2030. However, as part of that deal, the shutdown of several units originally scheduled to close in 2022 was postponed until 2024, in order to reduce gas consumption during the energy crisis.

For RWE, this is probably a good deal because it will lead to more operating hours before 2030 than originally planned. After 2030 it would likely not have been viable to operate the coal-fired power plants anyway, because of the high carbon price expected from the revised EU ETS.

While this deal saved several villages from destruction, it didn't save the iconic village of Lützerath as it was argued the lignite underneath the village was needed for energy security in Germany (RWE Power AG, 2023). This was contested by scientific groups (Oei et al., 2023), heavily criticised by civil society, and led to major protests.

Fossil gas and oil

Fossil gas remains a significant part of Germany’s energy mix, providing around 13% of electricity generation in 2024, mainly serving industry and heating needs (Bundesnetzagentur, 2025a). While renewables have increased their share substantially, gas-fired power plants continue to play a crucial role in balancing the grid, especially during periods of low renewable output.

The previous government adopted a transitional approach by approving four new gas-fired power plants to operate initially on fossil gas, with planned conversion to hydrogen between 2035 and 2040. In response to the geopolitical risks following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Germany diversified its fossil gas imports by entering long-term LNG partnerships with countries such as Qatar, the US, and Senegal (Tagesschau, 2022). While this strategy enhances short-term energy security, it carriers significant long-term risks. These include the lock-in of Germany’s energy system into continued fossil fuel dependence. At the same time, such partnerships may delay the energy transition in partner countries. This raises serious concerns about international climate justice, as wealthier nations secure energy security at the cost of sustainable development paths elsewhere. Moreover, reliance on LNG extends geopolitical vulnerabilities by creating new dependencies in a volatile global energy landscape.

The new coalition agreement recognises the necessity of moving away from fossil gas towards a climate-neutral energy system. Yet it also plans to subsidise substantial new fossil gas capacity through a unilateral tendering of 20 GW gas-fired power plants (Tagesschau, 2025).

This approach raises concerns about creating long-term fossil gas lock-in, especially given the option to use carbon capture and storage (CCS), which could lead to prolonged reliance on imported fossil gas (Agora Energiewende, 2025b).

While some fossil gas plants will be repurposed as reserve capacity to reduce electricity price spikes during rare peak demand hours, their overall impact on average electricity prices is expected to be limited. Subsidising fossil gas capacity risks weakening market incentives for demand flexibility and storage investments, essential to integrating renewables efficiently.

To mitigate these risks, it is critical that any fossil gas support is strictly conditioned on clear, enforceable commitments for conversion to hydrogen, alongside parallel expansion of hydrogen infrastructure. Without such safeguards, there is a danger that fossil gas will remain a costly and climate-damaging crutch rather than a true bridge to a sustainable energy future.

Nuclear

In April 2023, Germany disconnected its last nuclear power plant from the grid, marking the official end of domestic nuclear energy production. Originally planned for 31 December 2022, the shutdown was postponed to 15 April 2023 due to the gas crisis. This decisive step enhances investment certainty for renewable energy and lays the foundation for a truly sustainable electricity system. As of 2024, the remaining share of nuclear power in Germany's electricity consumption comes exclusively from imports, accounting for roughly one quarter of imported electricity (Agora Energiewende, 2025a).

Industry

The industry sector in Germany made up approximately one-fifth of Germany’s total emissions in 2024, emitting 153 MtCO2e (UBA, 2025c). Emissions from the sector increased minimally by 0.1 MtCO2e in 2024 compared to 2023.

Chemical, steel, cement, paper and glass production account for 80% of Germany’s industrial emissions (Kędzierski, 2024). Annual reductions and fluctuations, including the increase in emissions in 2024, have been largely driven by economic factors rather than by targeted policies. To reduce emissions more quickly and more consistently, the sector needs to decrease fossil energy use and electrify processes (Expertenrat für Klimafragen, 2023). The sector remains highly dependent on fossil fuels which, in 2022, accounted for nearly 60% of the sector’s energy consumption (IEA, 2025b). The sector is particularly reliant on fossil gas. The sector’s reliance on fossil fuels makes it vulnerable to supply shortages and price shocks. Since 2022, high fossil fuel prices, especially for fossil gas, have caused many industries to decrease production. As a result of the reduced industrial activity, emissions in 2024 have decreased by approximately 16.5% since 2021. In 2024, emissions were 17 MtCO2e lower than the sector’s annual emissions reductions target.

In its latest emissions projections report, the Federal Environment Agency (UBA) adjusted its emissions projections for the sector to better reflect Germany’s stubbornly high energy prices and decreased industrial output. In its 2025 report, the UBA assumes that output of energy-intensive industry will not fully recover by 2030. Therefore, the agency projects the sector will emit at a level below its annual emission targets until 2030. The 2025 report estimates the sector’s emissions will total 116 MtCO2e in 2030.

The new government’s policy package for the industry sector, as outlined in its coalition agreement, focuses on making German industries more globally competitive, but also extends and expands many of previous government’s policies and actions to decarbonise industry.

Key policies from the previous government included exempting industry from the renewable energy levy, reducing the electricity tax rate, reserving free allocations in the EU ETS, and introducing “Carbon Contracts for Difference” (CCfDs). The new government explicitly states its intent to enable the use of carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology to mitigate emissions from industrial processes, in particular for steel production. Details are yet to be defined.

The EU Emissions Trading System (ETS), which covers emissions from large-scale industrial installations and production facilities, is the main driver for emission reductions in Germany’s industry sector. The revised 2030 target for reducing emissions by 62% compared to 2005 under the EU ETS provides a strong signal for industry to decarbonise more rapidly (IEA, 2025b). The EU ETS reached record CO2 prices in 2023, breaching EUR 100t/CO2, averaging at nearly EUR 85t/CO2 (Twidale et al., 2023). However, prices declined substantially in 2024. The average price in 2024 fell to approximately EUR 65/tCO2 (UBA, 2025b); a price level significantly lower than projected by the UBA.

As a result, the UBA downgraded its carbon price projections until 2030: in 2030, the allowance price is now forecast to only reach EUR 95t/CO2 in 2030. For reference, the UBA’s previous projections report indicated the allowance price would be greater than EUR 120t/CO2 in 2030. The previous government introduced CCfDs to incentivise investments in low-carbon technologies in particularly energy-intensive industries. CCfDs guarantee a certain fixed price for low-carbon industrial products and processes that are not yet price competitive. If the market carbon price (e.g., EU ETS) falls below this fixed price, the government pays the difference—reducing financial risk and incentivising decarbonization. CCfDs mitigate the risk that industries do not invest in low-carbon solutions, even if such investments already pay off in the long term.

The government awarded the first group of companies with CCfDs in October 2024. In total, EUR 2.8bn was awarded to 15 companies (Amelang and Wehrmann, 2024). These companies intend to reduce emissions by 60% over the next three years and by 90% in 15 years, relative to when employing conventional technologies. The government projects the first round of CCfDs will reduce emissions by cumulative 17 MtCO2e between 2024 and 2030.

A second bidding round for CCfDs, worth EUR 19bn, was planned for the end of 2024 (BMWK, 2023b). However, the second round did not materialise as planned because of the change of government (Dietz-Polte and Ruepp, 2025).

The new government’s coalition agreement indicates that it will continue funding programmes to decarbonise industry, including CCfDs (Amelang et al., 2025). However, it has not specified the amount and period of funding. The duration for which the federal budget can sustain such a high-cost intervention also remains uncertain. The lower than projected EU ETS prices further complicate the potential for CCfDs to function as intended (Kędzierski, 2024).

Electrification is another key factor for decarbonising Germany’s industry sector. Relatively high electricity prices pose a major challenge to industrial electrification. To alleviate the financial burden of the high electricity prices, the previous government reduced the electricity tax for the industry sector at the end of 2023, lowering it from 1.537ct/kWh to the EU’s minimum rate of 0.05ct/kWh (Bundesregierung, 2023). The new government plans to retain the reduced tax rate (Bundesregierung, 2025). However, the coalition agreement does not specify for how long the government plans to extend the reduction.

Transport

In 2024, Germany’s transport sector emitted 143 MtCO2e and accounted for approximately 20% of the country’s total emissions. Overall, emissions from transport decreased by 1.4% in 2024 compared to 2023. Emissions from several sub-sectors within the transport sector—notably aviation—are increasing.

Emission reductions are not occurring fast enough to achieve the government’s targets. According to the government, transport sector emissions need to be reduced to 79 MtCO2e in 2030. Transport emissions in 2030 are expected to overshoot the target by 36 MtCO2e (UBA, 2025c).

Additional, ambitious action is required to reach the 2030 emissions reductions target. However, the new coalition government’s proposed policies for the transport sector are inconsistent and will likely slow sectoral emissions reductions.

New government’s transport policy portfolio

The new government’s coalition agreement sends especially mixed signals for the decarbonisation of road transport, which accounts for the majority of the sector’s emissions. In the coalition agreement, the new government explicitly rejects the idea of electric vehicle (EV) sales targets and, instead, advocates for a technologically neutral approach to reducing emissions from road transport.

In doing so, the new government has retracted the previous government’s target to register 15 million EVs by 2030, which Germany is not on track to achieve. The coalition agreement emphasises the government’s commitment to Germany’s auto industry and asserts the government will oppose penalties incurred by German automakers that fail to meet the EU’s fleet-wide CO2 emissions targets; a move that would be in direct violation of the EU’s regulation.

The new government also intends to increase the commuter tax credit, reduce the company car tax, lower the cost of driving licences, and introduce purchase incentives for internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles that use plug-in-hybrid systems and EVs that use ICE range extenders: actions that will likely prolong the production of ICE cars, increase the number of ICE-powered vehicles on German roads, and, as a result, increase emissions from transport.

At the same time, the new government plans to introduce purchase incentives for EVs, a positive development after the previous government suddenly and prematurely eliminated all purchase incentives for light and heavy-duty EVs at the end of 2023 because of federal budget cuts.

Alongside purchase incentives, the coalition agreement proposes tax benefits for private and commercial EV owners, as well as a programme to support the uptake of EVs by low and middle-income households. The government also plans to accelerate the development of EV recharging and hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicle (FCEV) refuelling infrastructure; FCEVs are expected to be crucial for transitioning heavy-duty, commercial trucking.

The coalition agreement features measures to increase the modal shares of rail and aviation, which, if implemented, would have opposite impacts on the sector’s emissions. It plans to shift more transport to rail and reduce emissions from rail. Specifically, the government proposes to increase investment in rail infrastructure, accelerate electrification, incentivise freight rail transport, and continue funding the “Deutschlandticket,” the nationwide public transit ticket, which was set to expire at the end of 2025.

Simultaneously, the new government’s proposals for the aviation sector will likely continue to increase emissions in the name of bolstering the competitiveness of European airlines. The government plans to reduce the aviation tax and eliminate the previous government’s minimum quota for sustainable aviation fuels.

Road transport

Road transport is responsible for the largest share of transport volume and emissions in Germany. In 2023, 80% of all passengers and 55% of all freights was transported on roads. Road transport generates over 95% of the sector’s total emissions (IEA, 2025b). Therefore, reducing emissions from road transport—in particular through electrification—is key to reducing overall emissions from the sector.

However, current policies and actions to electrify road transport appear insufficient. Both the existing vehicle fleet and new vehicle registrations remain dominated by ICE vehicles. At the end of 2024, 1.6 million passenger BEVs were registered in Germany, accounting for less than 3.5% of the country’s total passenger car stock (EAFO, 2025).

Demand for EVs decreased in 2024 from 2023. Registrations of new BEVs decreased by 27% in 2024 compared to 2023 (KBA, 2025); significantly diverging from the government’s projections for new BEV registrations for 2024 (UBA, 2024a). This slowdown is likely linked to the previous government’s abrupt elimination of the federal EV purchase subsidy scheme at the end of 2023. The former purchase incentive totalled EUR 6,750 (EUR 4,500 from the government and EUR 2,250 from manufacturers) for new BEVs retailing at EUR 45,000 or less (ADAC, 2023a).

The new government’s proposed purchase incentives may future bolster demand for EVs. The exact structure and scope of the planned purchase incentives is unclear. It is important to note that, even without the implementation of new policy, data for the first half of 2025 suggests a rebounding of EV registrations in comparison to 2024.

Charging infrastructure for EVs is expanding. As of May 2025, nearly 170,000 public charging points were operational (Bundesnetzagentur, 2025b); an increase of almost a factor of five since 2020 (BMDV, 2024). The previous government planned to operationalise one million public EV charging points by 2030 (BMDV, 2022). It is unclear whether the new government intends to retain this target.

The EU strengthened the CO2 emissions performance standards for light and heavy-duty vehicles in 2023 and 2024, respectively. New passenger cars and vans reduce emissions by 15% in 2025, 55% in 2030, and 100% in 2035; effectively phasing out the production of new ICE vehicles by 2035 (Velten et al., 2024). New heavy-duty vehicles need to reduce emissions by 65% in 2035 and 90% by 2040.

The government delayed the adoption of the new CO2-standards for cars and vans by negotiating an exception for “CO2 neutral” e-fuels. The use of e-fuels is problematic for several reasons: there are no cars that run exclusively on e-fuels, e-fuels will remain significantly more expensive in comparison to directly using electricity from batteries, and e-fuels are not zero emissions. Vehicles fuelled by e-fuels, as defined by EU’s Renewable Energy Directive methodology, are expected to use six times more electricity than EVs and emit 61 gCO2e/km in 2035 (Transport & Environment, 2023). The use of e-fuels enables the continued production of diesel and petrol cars and, in doing so, hinders the transition towards fully electrified vehicles.

Rail transport

Rail transport, which is significantly less emissions-intensive than road transport, accounted for only 10% of total passenger transport volume and 20% of total freight transport volume in 2023 (Bundesnetzagentur, 2024).

The previous government and Deutsche Bahn, the national rail company, committed to jointly invest EUR 86bn into the country’s rail network by 2030. Half of the investment will be covered by income generated from increased highway toll fees for heavy-duty trucks. The new government’s coalition agreement states that the government will increase investment in the German rail network but does not specify the level or source of investment.

Germany’s nationwide public transit ticket, the “Deutschlandticket,” is the government’s flagship measure for enabling a modal shift away from passenger cars to rail and other forms of public transit. The Deutschlandticket grants access to all modes of local and regional public transit. The government introduced the ticket in May 2023 for EUR 49 per month. In January 2025, the ticket price increased to EUR 58 per month. By April 2025, over 14 million Deutschlandtickets had been issued (Koch et al., 2025).

Estimates for the ticket’s short-term impact on emissions range from reductions of 4.2 MtCO2e per year to 22.6 MtCO2e per year by 2030 (Expertenrat für Klimafragen, 2024). The long-term impact may be more significant, given the single ticket system makes using public transport more accessible. Funding for the ticket was set to expire at the end of 2025. However, the new government intends to continue funding the ticket indefinitely without increasing the monthly ticket cost until 2029.

The previous government set ambitious targets for public transport volumes. Specifically, the government planned to double the volume of rail passenger transport by 2030 compared to 2020 levels. The new government’s coalition agreement does not explicitly reference this target.

Carbon price on transport fuels

Germany’s national emissions trading scheme for fuels (Brennstoffemissionshandelsgesetz – BEHG) sets a carbon price that remains far too low to meet the government's emissions reductions target without other supportive measures. The fixed carbon price was increased from EUR 30/tCO2e to EUR 45/tCO2e in 2024 (UBA, 2025b). This price level results in a relatively small markup on fuel prices, limiting the scheme’s impact on greenhouse gas emissions from the transport sector. From 2026, new allowances will be auctioned in a price range of EUR 55tCO2e to EUR 65/tCO2e (German Government, 2020a). In 2027, the national scheme will be merged into the revised EU ETS for transport and buildings.

Based on the current policies, the UBA estimates an allowance price of at least EUR 350/tCO2e, would be necessary to reduce emissions to the sectoral target (Harthan and Repenning, 2022). The UBA, in its latest projections report, (Federal Environment Agency, 2024) assumes an increase to above EUR 100/tCO2e after 2030 and reaching a maximum of nearly EUR 240/tCO2e in 2050 (UBA, 2025c).

All proceeds from the German ETS will either be reinvested in climate protection measures or returned to citizens. The German ETS generated record revenue in 2024, totalling approximately EUR 13bn (UBA, 2025b). The increase in revenue is linked to the 2024 increase in the carbon price. The revenue was channelled into the government’s Climate and Transformation Fund (KTF), which functions as the principal economy-wide source of climate finance (UBA, 2023a). Although the government has agreed to return ETS revenues to consumers, this payback will likely only begin in 2028, if at all. The current government has not yet decided to implement such a measure.

Buildings

The buildings sector in Germany made up about 15% of Germany's total emissions in 2024, emitting 101 MtCO2e (UBA, 2025c). While emissions fell by 2.3% compared to the previous year, the decline was smaller than in past years. Further, this reduction is largely attributable to warm weather, which reduced fossil fuel consumption in space heating, and not structural improvements (Expertenrat für Klimafragen, 2025).

Emissions from this sector have declined since 1990, but only incrementally so in the last 10 years. The sector remains off track for its 2030 target. By 2030, the Climate Change Act foresees a limit of 67 MtCO2e for buildings, which current projections suggest will be exceeded by 10 MtCO2e. Cumulatively, the sector is expected to miss its 2021–2030 emissions budget by around 110 MtCO2e (UBA, 2025c).

The previous government coalition proposed a 65% renewable energy requirement for new heating systems from 2024 (Federal Ministry of Economics and Climate Protection (BMWK), 2023). After strong political opposition, even from within the coalition, the responsible ministry revised its draft law, delaying implementation in some regions until 2028 and allowing more exceptions, including for wood-based heating. The so-called “Heating Act”, passed in September 2023, promotes heat pumps and district heating, but only applies when heating systems are newly installed or replaced. Existing systems can continue operating, and broken gas or oil systems may be repaired. In case of irreparable failure, transitional rules and exemptions apply.

Municipalities must submit these plans by mid-2026 (for those over 100,000 inhabitants) or mid-2028 (for smaller ones). Financial support of up to 70% was introduced to support the switch (Bundesamt für Wirtschaft und Ausfuhrkontrolle, 2024). Nationwide, roughly one-third of municipalities have started, while only around 13% have completed their heat plans (Collins, 2025).

In parallel, the Heat Planning and Decarbonisation of Heating Networks Act, effective from 2024, obliges federal states to develop plans for GHG-neutral heating by 2045, with interim targets of 50% climate-neutral heat by 2030 and 80% by 2040.(BMWSB, 2023)The heated debate surrounding the "Heating Act” also affected the market and led to uncertainty among consumers: After record-level heat pump sales in 2023, sales plummeted in 2024. Just under 200,000 heat pumps were sold – while the former government’s target were 500,000 per year from 2024. In 2025, heat pump sales are picking up again, but the outlook remains uncertain (Agora Energiewende, 2025a).

In 2025, the newly-elected government included major revisions to the heating law in its coalition agreement. While the agreement refers to repealing the “Heating Act,” the coalition emphasised that the transition away from fossil heating remains on track but will rely less on rigid mandates. While the coalition claims to remain committed to decarbonising heating, this decision has sparked sharp criticism from climate experts and environmental groups. Critics argue that scrapping the law risks undermining hard-won progress, increasing uncertainty for consumers and the industry, and slowing down the urgent transition away from fossil fuels. Revised legislation is expected by late 2025, with new provisions likely taking effect from 2026.

The energy efficiency of the German buildings stock is poor, and energy consumption for space heating stagnates on a high level. This is partly due to rising per-capita living space, and partly due to low renovation activities. The annual renovation rate fell to 0.7% in 2024 – a new low. Existing policies, such as subsidies for energy efficiency measures of 35%, are a start, and should be sustained, but unable to significantly improve the energy efficiency of the German buildings stock without further (regulatory) measures. Almost 45% of living space falls into the three worst energy performance classes (F, G or H) with a consumption of over 160 kWh/m2 (Agora Energiewende, 2025a).

The former government put the improvement of existing buildings in the centre of its policies, e.g. by allocating more funding to renovation activities rather than new-builds. The new government pursues a different approach, introducing incentives to build more new houses, which are resource- and land-intensive and associated with high embedded emissions.

Germany’s national emissions trading scheme (BEHG) covers all non-ETS sectors, including the buildings sector. Companies selling fossil fuels have to purchase certificates for the carbon content of those fuels, and pass on the additional financial burden to the end consumers through an increased price.

The scheme started in 2021 with an initial price of EUR 25 per tonne of CO2. It was meant to increase annually, but in 2022 the government postponed the increase because of the high energy prices driven by the invasion of Russia in Ukraine. As of 2024, it is raised to EUR 45 per tonne of CO2. In 2025, the price increased further to €55 per tonne, marking the last year of fixed pricing before the system transitions to a market-based auction in 2026.

As carbon prices rise, operating fossil-based heating systems will become increasingly expensive. While some informed building owners may anticipate this and invest in cleaner options, many are likely to stick with familiar systems that have lower upfront costs. With the new government’s decision to repeal the Heating Act and replace it with a less prescriptive framework, this regulatory uncertainty could compound risks for consumers. Without clear mandates or bans on fossil heating, rising carbon costs may disproportionately impact low-income homeowners and tenants.

Agriculture

The agricultural sector in Germany emitted 62 MtCO2e in 2024, nearly 10% of Germany’s total emissions (UBA, 2025c). Over the last two decades, emissions in the sector slightly declined. Methane released through livestock’s enteric fermentation emits approximately half of the sector’s emissions. Nitrous oxide from agricultural soils is another key emissions source.

In 2024, emissions from the agricultural sector remained below the sectoral limit set by the Climate Change Act. For 2030, the Climate Change Act foresees a sectoral limit of nearly 59 tCO2e/yr, which the UBA forecasts will be met with implemented policies and actions (UBA, 2025c). However, to reach climate neutrality by 2045, emissions in this sector need to be reduced rapidly and significantly.

Meat consumption increased by nearly 1% in 2024 relative to 2023 (BMEL, 2025), which was also reflected in increased meat production (BMEL, 2024b). The level of meat consumption is significantly greater than the world average (Climate Action Tracker, 2018). While demand for meat products increased, demand for plant-based products continued to grow in Germany, which is the largest market for plant-based foods in Europe: plant-based product sales volume increased by 7% in 2024 compared to 2023 (GFI Europe, 2025).

Forestry

In 2024, the government’s Federal Forestry Inventory found that German forests are no longer a net-CO2 sink but instead a net-CO2 source (BMEL, 2024a). As a result, Germany’s entire LULUCF sector is now emissions source (Expertenrat für Klimafragen, 2025). This development seriously threatens Germany’s target to reach climate neutrality by 2045, as enshrined in the Climate Change Act. The Climate Change Act expects the LULUCF sector to remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere by 40 MtCO2e in 2045. The government’s Council of Experts on Climate Change (ERK) is unable to conclusively determine whether the LULUCF sector will be able to develop in a net-CO2 sink.

Waste

The waste sector emitted 5.4 Mt MtCO2e in 2024 (UBA, 2025c). The sector’s emissions have decreased by over 85% since 1990.(UBA, 2023b) This significant reduction has been mainly achieved by ending the disposal of untreated residential waste and the increased use of energy and materials from waste (Umweltbundesamt, 2017). Since 2005, landfilling of biodegradable waste has been prohibited in Germany. From 2024, CO2 emissions from waste incineration are part of the emissions trading scheme for fuels (BEHG).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter