ANALYSIS: Reliance on sinks and support of fossil fuels undermines Australia's climate action

Summary

Authors: Thomas Houlie, Maria José de Villafranca, Bill Hare

We've just completed our analysis of Australia's climate action and, unfortunately, it seems the Australian government has failed to deliver on its promise to “take the country forward on climate action” as it had promised.

Australia's massive reliance on sinks in the land sector obscures its ongoing support for fossil fuels. Our rating remains "Insufficient."

The government projects a 37% emissions reduction by 2030, taking into account the emissions from all sectors, but also including the land sector. This falls significantly short of its 43% (by 2030) target and even more short of the 61% or greater reduction by 2030 it would need to achieve to be 1.5˚C aligned (when complemented with additional financial transfers).

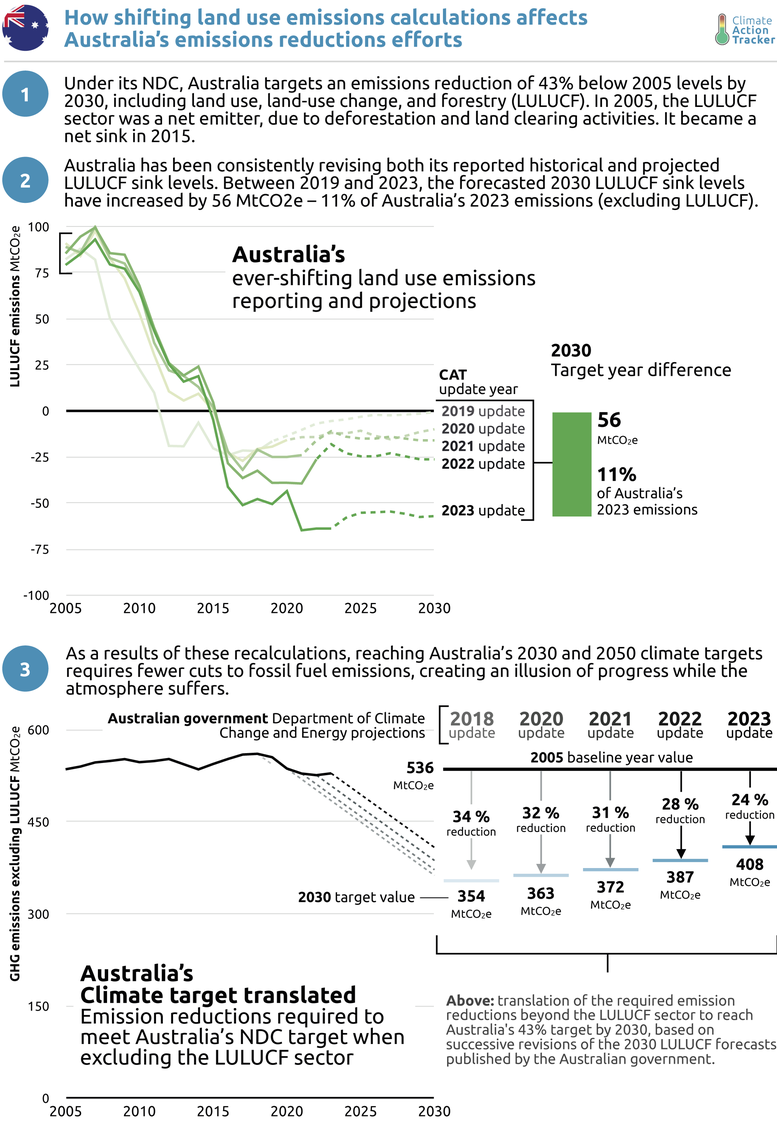

While a 37% reduction by 2030 seems like a significant improvement on the 32% reduction in the government’s 2022 projections, unfortunately this is mainly due to the increased projected sink – carbon sequestration - in the land sector.

Australia's land sector sink projection for 2030 increased from -33 MtCO2e in 2022 to -57 MtCO2e in 2023. If the government had used the 2022 land sector sink projection, the current projected reductions by 2030 would only be 33% instead of 37%.

The impact of Australia's land sector accounting on its climate targets

Far from achieving a 43% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions based on the current land sector projections for 2030, Australia would only achieve a 24% percent reduction in fossil fuel and other greenhouse gas emissions - excluding land use change and forestry – if it were to reach its 2030 target. This is one reason why the CAT excludes the land use sector in assessing a country's climate action, because it can hide a multitude of issues, as is the case with Australia.

The larger the land sector sink, the smaller the emissions reductions needed in other sectors to achieve the climate target. Land sector accounting is critical because it effectively enables more fossil fuel emissions go on. The CAT prefers to focus on actual emission reductions, which we believe governments must prioritise.

Australia's emission reductions in fossil fuel and related GHG emissions are expected to be only 17% below 2005 levels by 2030 without counting the land sector's sinks, a far cry from the apparent 37%. As we show in this update, this is a consistent and persistent pattern for Australia.

These two graphics below show how Australia has managed to hide its lack of effort, and create an illusion of progress:

Current policies still lacking

Australia's main emissions reduction focus has been on emissions from large industrial facilities under the Safeguard Mechanism reform passed last year.

The Safeguard Mechanism (SGM) covers large industrial facilities, which accounted for 30% of Australia’s 2022 emissions. The government introduced reforms to it in March 2023 to decrease net emissions from this sector by a projected 32% below 2022 levels by 2030, or an estimated 9% below 2005 levels.

Unfortunately, real emissions from the SGM are uncertain since the facilities it covers are allowed to use offsets, rather than reduce emissions at source.

SGM facilities can purchase Australian carbon credit units (ACCUs), which are substantially generated from land sector activities, such as human-induced regeneration. These offsets are unlikely to be real, additional or permanent. The SGM has essentially become a licence for fossil fuel facilities to continue emitting or even expand. The SGM reform assumes significant new fossil fuel projects to come online, including new carbon-intensive gas fields and coal mines.

Meanwhile gas exports projected to rise and rise

Australia seems hell-bent on keeping its place as one of the world's largest exporters of fossil fuels. At the end of 2023, Australia still had 100 coal, gas and oil projects in the pipeline. Few have been cancelled.

Key fossil gas developments like Woodside Energy's Scarborough gas field and the North West Shelf plant extension in Western Australia, or the Santos Barossa offshore gas field and Beetaloo fracking project in the Northern Territory, will perpetuate fossil fuel extraction, production and exports for decades. The government continues to subsidise major new gas developments such Tamboran Energy's massive new LNG processing plant at Middle Arm in Darwin.

Unless changed, the offsetting system under the government's new Safeguard Mechanism will permit this to happen. In short, no one should be surprised if real emissions from its facilities do not decrease significantly from present levels by 2030.

The Australian government's focus appears not to be on emission reductions at source, but rather on facilitating activities that produce emissions using offsets and/or the promise of carbon capture and storage (CCS) in the future.

As a consequence, the fossil fuel industry continues to be empowered by the government’s support for false solutions like offsets and CCS, which do not only appear to be fundamentally flawed, but also fail to address the massive exported emissions from these projects.

Renewables the one bright spot

The one bright spot in Australia's climate policy landscape is the rollout of renewables in the power sector. Power generation emissions are projected to decrease by close to half from 2023 - 2030, in part due to the Rewiring the Nation initiative, federal incentives, & state-level policies and targets.

In November, the government responded to the slowdown in investment in renewables with a very important Capacity Investment Scheme overhaul that should help put Australia back on track to reach its renewable energy target for 2030.

Without the Capacity Investment Scheme overhaul, it seemed increasingly likely that Australia would miss its stated 82% renewable penetration target by 2030. While this is a major step forward, the 82% target still falls short of the 95-96% renewables that would be 1.5˚C compatible.

Measures for other sectors are still lacking. While transport is the fastest growing source of emissions, the government has yet to propose efficiency standards for motor vehicles. It stands alone in the OECD in this context.

There has been little to no material development on how Australia will achieve its net zero by 2050 target beyond the flawed reports of the previous government. Australia is still far off achieving its #netzero by 2050 target, with the current strategy only planning to cut emissions by 60% thanks to unclear “technology breakthroughs”.

The government is known to be preparing a new net zero strategy. However, it is unclear when this will be released.

Read the CAT Australia update

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter