EU Missing in Action?

What the EU must do to retain its climate leadership

by Michael Petroni, Mia Moisio & Sarah Heck

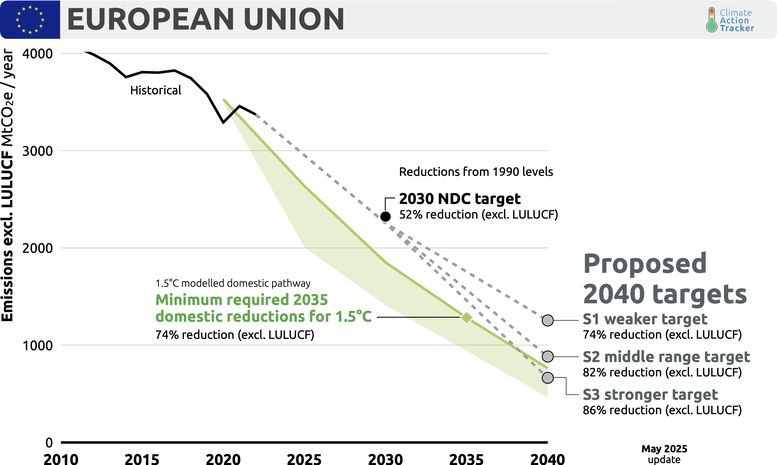

The EU is at risk of weakening its climate leadership, and its pathway to limit warming to 1.5˚C is in question, as its 2035 NDC is still missing and political divisions threaten to adopt a 2040 commitment that is less ambitious than the “at least 90%” emissions reductions below 1990 levels" proposed by its own scientific advisory board.

The more the 2040 target is watered down—through lower ambition, delays, or the use of international offsets—the further the EU will drift from the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C goal. At a time when global leadership is urgently needed, the EU cannot afford to be missing in action.

To retain its climate leadership the EU must:

- Reaffirm its commitment to a 2040 target reducing its domestic emissions of at least 90–95% (incl. LULUCF), in line with the recommendations of the European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change (ESABCC). Less ambitious targets essentially undermine its net zero target by 2050.

- Reject the use of international offsets to weaken this target and meet that target through real, domestic emission reductions.

- Set a strong 2035 target, with an at least 78–80% reduction with LULUCF (or 74% excl. LULUCF), which ramps up ambition with steep reductions between 2030 and 2035.

- Protect and if possible increase climate finance in the next EU budget and deliver on international partnerships to support a global transition to net zero emissions.

In 2024, the European Commission planned to adopt a 2040 climate target of at least a 90% reduction in emissions below 1990 levels, but this ambition is now unravelling. The Commission dropped the release of its 2040 target from its workplan in March 2025. No submission of a 2035 target is in sight, no updated timeline has been communicated, and now Member States – including Italy, Poland and Hungary – are pushing to opt for weaker 2040 target options.

Current developments suggest that there is not enough vocal support at the European Council level for the 90% target without compromises, and political will is dwindling. EU President Poland is pushing to delay a decision until after its presidential elections in May.

A divided EU — and what the numbers say

The EU’s climate ambition is now up for negotiation, and the bloc is increasingly divided. Some countries want to dilute targets, while others are still pushing for action based on the advice of the scientific advisory board.

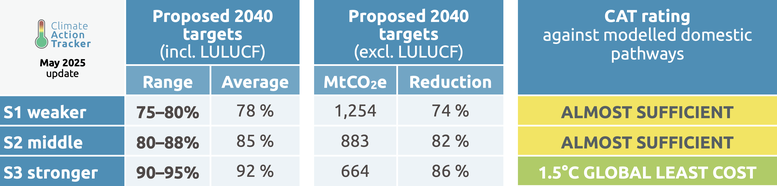

Three options for a 2040 target from the EU’s impact assessment are on the table: S1 is the weakest scenario which assumes a reduction of up to 80% (incl. LULUCF) compared to 1990 and is consistent with the minimum required under the European Climate Law. S2 is slightly more ambitious than S1 and anticipates a reduction of 85–90% (incl. LULUCF) compared to 1990. S3 sees a reduction of 90–95% (incl. LULUCF) compared to 1990 and is the only scenario consistent with the ESABCC’s recommendation.

The Climate Action Tracker (CAT) has analysed what the different 2040 options on the table could mean for a 2035 target.

To derive 2035 targets, we assume the EU would take a linear approach – drawing a straight line from 2030 to the different 2040 reduction targets. None of these derived 2035 targets are 1.5˚C aligned. We would strongly advise against the EU taking such an approach because a lack of strong, near-term action puts the Paris Agreement's 1.5˚C limit in jeopardy and increases the associated risks.

If the EU is to have any chance of reaching climate neutrality by 2050, it must adopt an ambitious domestic 2035 target—74% or more (excluding LULUCF)—alongside a 2040 target of at least 90%, ideally 95% (incl. LULUCF), and achieve these reductions within its own borders. Otherwise it will not be possible to reach its own net zero target by 2050.

A 90% target is the scientific minimum

We agree with the EU’s own advisory body, the European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change (ESABCC), which has clearly stated that reducing emissions by less than 90% (incl. LULUCF) by 2040 is not in line with limiting warming to 1.5˚C.

Anything less than a 90% cut would completely rule out an EU 1.5°C-compatible trajectory. Worse, a proposed “compromise” would slow emission reductions between 2030 and 2035, relying on steeper cuts later, pushing the EU even further off track, putting the EU’s 2050 net zero target at risk and damaging its climate credibility. To be 1.5oC compatible, the EU needs to ramp up ambition with steep reductions between 2030 and 2035.

Undermining progress with international “offsets”

One of the most concerning developments is a push—led by the new government of Germany—to allow international carbon credits under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement to effectively reduce the ambition of the EU’s 2040 target.

For Article 6 to contribute to more ambitious global emissions reductions as intended under the Paris Agreement, it needs to be used to go beyond what is feasible to meet a 1.5°C trajectory within the EU’s borders. If at all, it would need to be used to go beyond a 90–95% reduction.

The EU rightly abandoned the use of international credits in 2021 after it flooded the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS) with cheap, low-quality credits, crashing prices, weakening incentives to reduce emissions and reducing the auctioning revenues. The EU’s 2030 target and its 2050 net zero target are defined to be met without offsets. The reintroduction of offsets would severely weaken the EU’s domestic ambition by opening the door to accounting loopholes and putting the achievement of the EU’s net zero target at risk.

Despite claims that new Article 6 credits should be “high quality,” the existing safeguards are insufficient to ensure this. It would be a risky step backwards that undermines the principle that climate targets should drive real, domestic emission reductions.

Climate leadership at risk

The EU has long-portrayed itself as a climate leader—especially in the absence of consistent U.S. leadership. But without credible near-term targets or strong commitments on climate finance, that leadership is in jeopardy.

The recent weakening or delay of several European Green Deal elements is casting doubt over the EU’s commitment to finance the net zero transition domestically and internationally. This includes the proposed flexibility in meeting the 2025 vehicle emissions standard and limiting the scope of its new emission reporting requirements in the private sector, exempting 80% of companies that were once covered.

With a growing climate finance gap and Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs) in need of renewed support, the EU must show that it’s still serious about international solidarity. If the EU doesn’t lead on climate finance, who will?

Europe took a strong stand in creating the Paris Agreement—and for a time, it led the world in turning that promise into policy. But that leadership is now in question. There is still time to act, but that time is running out fast.

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter