A government roadmap for addressing the climate and post COVID-19 economic crises

Attachments

Summary

The COVID-19 pandemic presents the world with an unprecedented policy challenge: not only will it have a severe impact on the global economy likely to exceed that of both the 2008-09 Global Financial Crisis and the Great Depression, it will take place against the backdrop of the ongoing climate crisis.

In acknowledging the magnitude of this unprecedented challenge, the priority for governments must first be the immediate emergency response focussing on saving lives, supporting health infrastructure, food availability, and the many other urgent social and economic support measures such as short-term job allowances, direct cash handouts to citizens, or targeted liquidity support to SMEs. But solving the COVID-19 crisis cannot come at the expense of solving the longer-term issue facing humanity: the climate crisis.

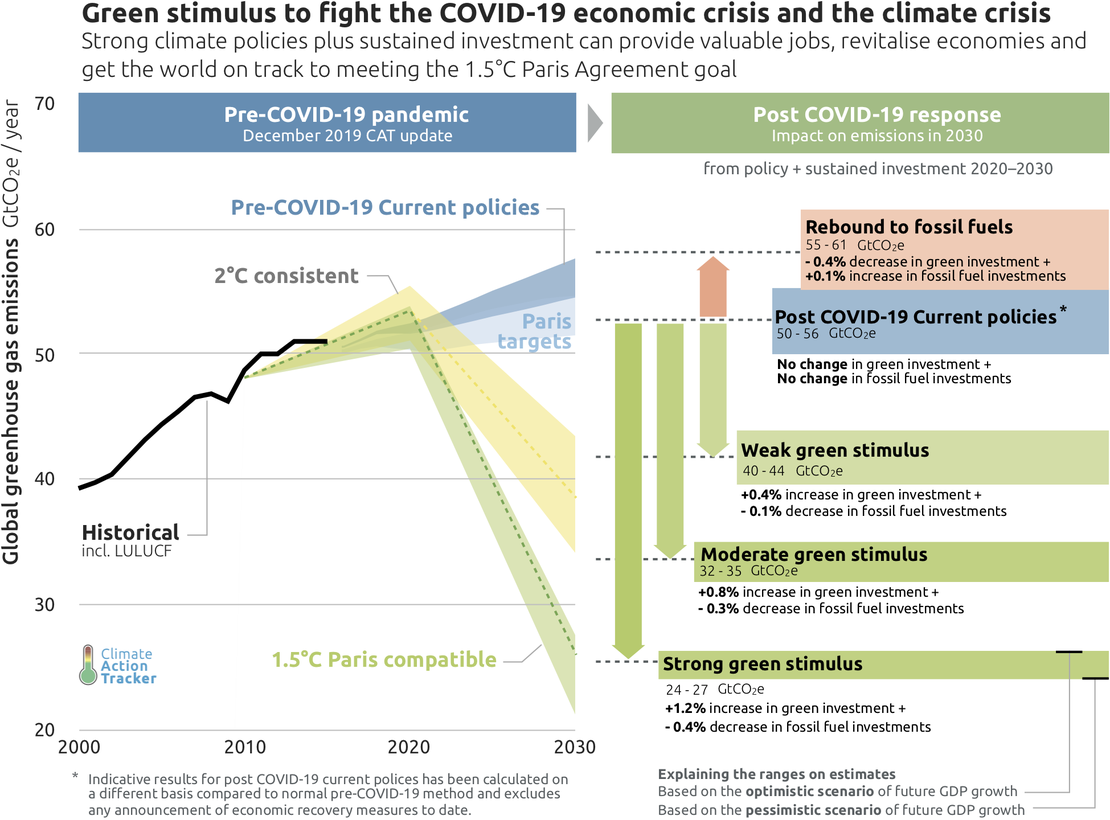

The question of how the economic recovery is designed remains crucial in shaping the long-term pathways for emissions and determining whether the Paris Agreement’s 1.5˚C temperature limit can be achieved. Our analysis points to strong economic and climate change advantages if governments were to adopt green stimulus packages in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conversely, if governments don’t roll out low carbon development strategies and policies - or roll back existing climate policies - in response to the coming economic crisis, emissions could rebound and even overshoot previously projected levels by 2030, despite lower economic growth in the period to 2030. This report shows that the future is for governments to choose. COVID-19 recovery presents both opportunities and threats to enhancing our resilience to climate change.

COVID-19 pandemic impact on emissions and GDP

The economic damage caused by the COVID-19 pandemic will undoubtedly cause global CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and industry to fall in 2020 in the range of 4 to 11% and possibly again in 2021 by 1% above to 9% below 2019 levels.

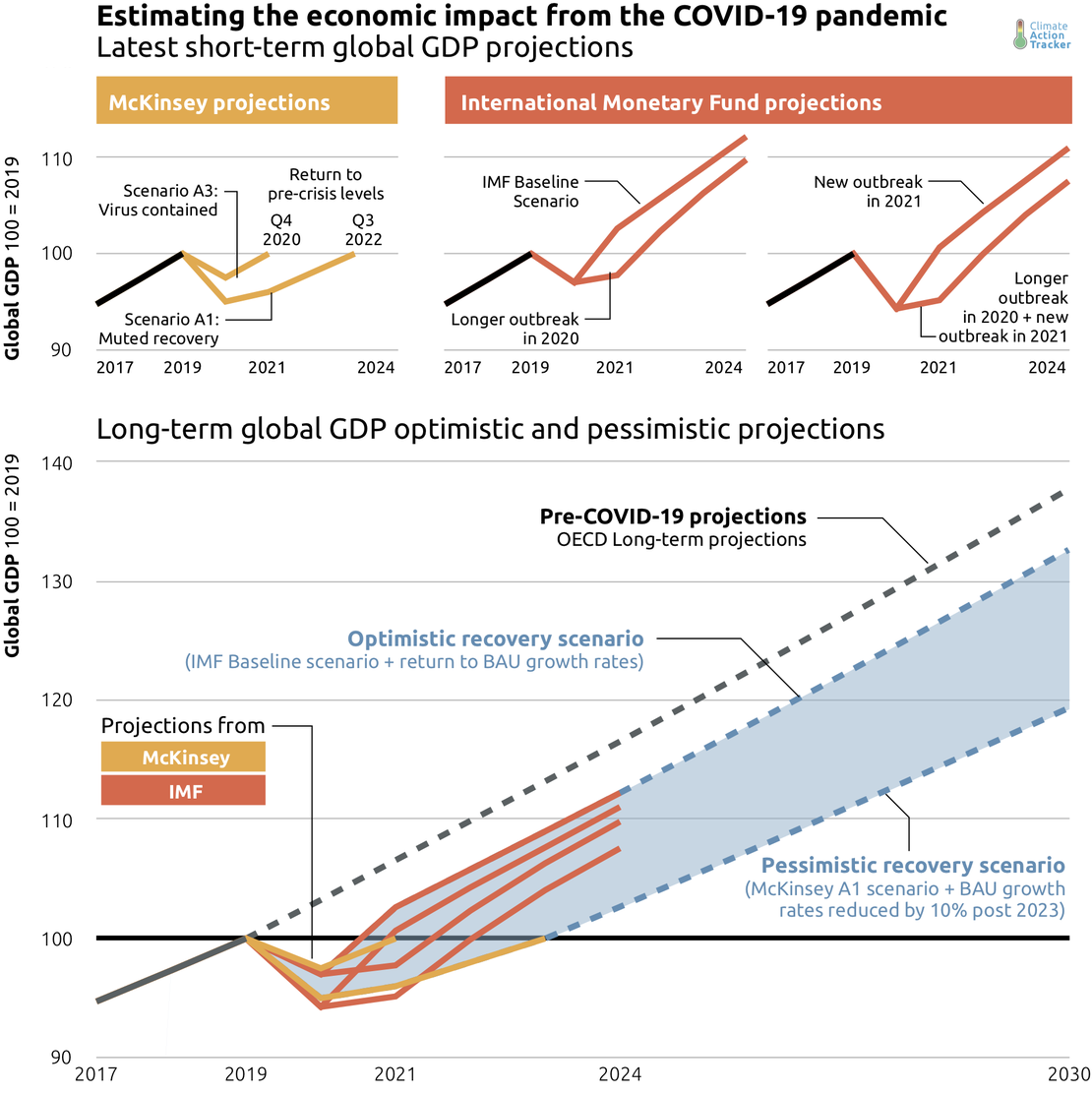

For the analysis, the CAT modelled two economic pathways: an “optimistic recovery” where economic growth rates eventually return to those projected before COVID-19, and a “pessimistic recovery” where growth rates take much longer to recover and don’t return to those levels.

It then combined these with five COVID-19 response scenarios: fossil fuel rebound, post-COVID-19 current policies, weak green stimulus, moderate green stimulus and strong green stimulus.

From our COVID-19 recovery scenarios, we find that strategies that invest in green energy infrastructure - including energy efficiency and low and zero carbon energy supply technologies - have by far the strongest effect on reducing emissions, irrespective of an optimistic or pessimistic economic recovery by 2030.

A green stimulus framework for policymakers

As governments grapple with the critical task of dealing with the very real impacts of COVID-19 on the health and welfare of their populations, they are now also developing their economic stimulus packages to assist in economic recovery.

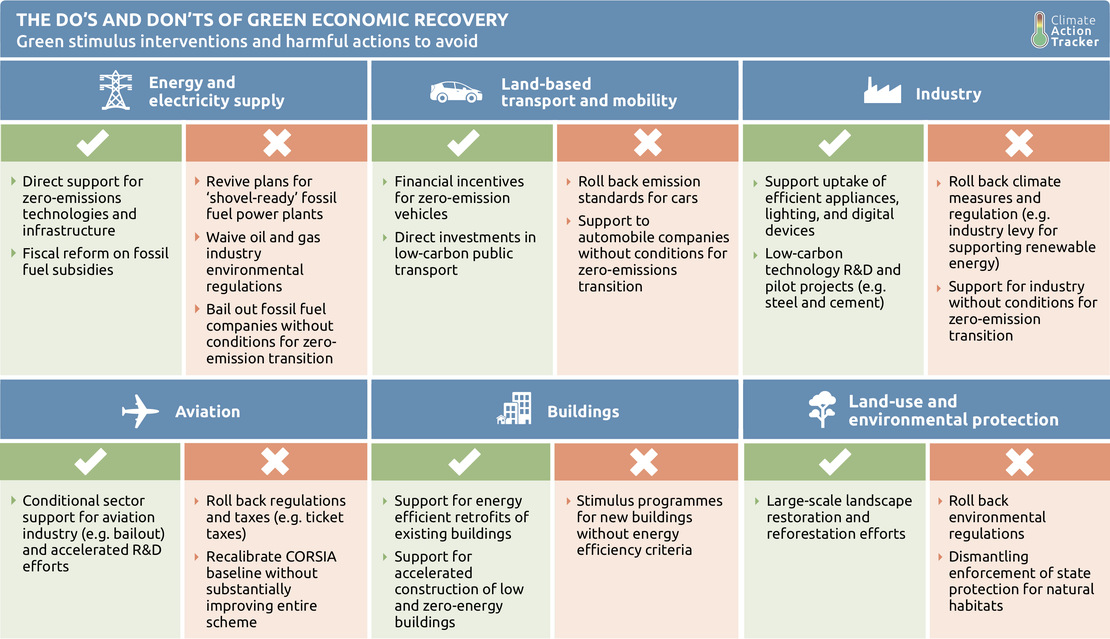

We have outlined a green stimulus framework that contains key criteria for policymakers to consider for any green stimulus interventions in order to successfully address short-term needs with long term benefits.

Preliminary proposals of green stimulus interventions under discussion

There are few initial proposals of “positive” green stimulus packages being drawn up by governments now, and some of those below are from the 2008-09 GFC economic recovery.

- The Austrian government announced on 17 April 2020 that any state aid to support Austrian Airlines should be tied to specific climate conditions, with options including a pledge to reduce short-haul flights, increased cooperation with rail companies, heavier use of eco-friendly fuels and bigger tax contributions.

- Many European policymakers have called for using the EU Green New Deal as an economic recovery package blueprint for EU Member States. An example of this would be to accelerate the implementation of the strategy’s ‘renovation wave’ to increase energy efficiency of existing buildings.

- The African Union and the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) agreed to work closely to advance renewable energy across the continent to bolster Africa’s response to COVID-19.

- GFC: Germany substantially expanded its programme to promote energy efficient retrofits through fiscal measures and concessional loans between 2008-2010 as part of its economic recovery package.

- GFC: The American Recovery Act of 2009 promoted the improvement of residential energy efficiency of over 800,000 homes between 2009-2012 with federal support, green stimulus interventions that triggered energy savings and created over 200,000 jobs.

Do no harm: actions to avoid

Meanwhile, fossil fuel-based industries are intensively lobbying for their future, pressuring governments to adopt policies and interventions that favour them but not the climate, and they are finding such favour in some quarters. We have listed these as “do no harm” examples of what governments should reject as they move forward.

- The US Senate is discussing a USD 2 trillion rescue package for automakers and a massive bailout to its oil and gas industry. In the US, the Environmental Protection Agency has moved to cancel the Obama-era fuel efficiency standards for new cars and dropped a raft of anti-pollution regulations to favour industry.

- In Australia Federal and State governments are pushing for the expansion of coal mines and LNG export facilities, without any acknowledgement that the world needs to move away from coal and gas.

- China approved in March 2020 five new coal-fired power plants with a total capacity of around 8 GW, more than the total for 2019.

- The South Korean government is planning a USD 825 million bailout of Doosan Heavy Industries & Construction Co. without any condition to promote renewables.

Even in the longer term, reduced economic growth arising from economic damage caused by the COVID-19 will not fundamentally change emissions in the direction needed to meet the Paris Agreement goals. Unless Governments take affirmative and positive action to ensure that the stimulus and response measures they put in place focus on low and zero-carbon development, there is a risk of a winding back of policies, resulting in emissions being even higher in 2030 than would otherwise have been the case.

Read more

To read the full analysis, including more details on the economic and emissions impact from the pandemic and sector specific recommendations in energy, transport, industry, aviation, buildings and land-use, click on the button below.

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter