Climate Governance in Colombia

Attachments

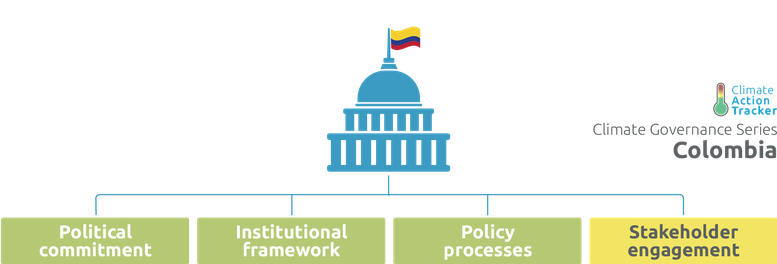

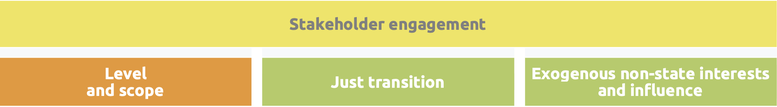

The CAT Climate Governance series seeks to produce a practical framework for assessing a government’s readiness - both from an institutional and governance point of view - to ratchet up climate policy and implement adequate transformational policies on the ground, to enable the required economy-wide transformation towards a zero emissions society.

Our methodology

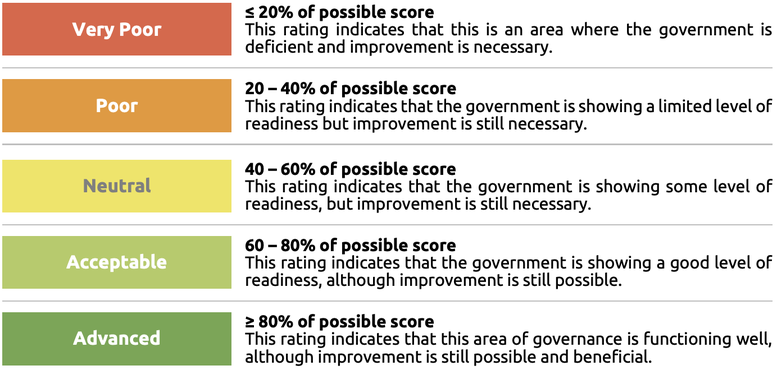

We have set up a framework that assesses and scores a number of indicators, where we rate various aspects of governance. This allows us to establish a common basis on which to compare climate governance across countries as well as identify areas of improvement and highlight positive developments. We have applied this framework at a national level only.

For more detail on our methodology, see here: methodology page.

Assessment of national level readiness

President Gustavo Petro is committed to transitioning Colombia away from a fossil fuel-based economy to one centred on renewable energy, and to fight deforestation. He assumed power in early August 2022 and has begun delivering on some of his election promises, though much work remains. Legislation on banning fracking, introduced in the first few days of his tenure, has not yet been adopted.

There is support in his cabinet for the transition, though individual ministers differ on the speed of the transition and whether new fossil gas developments should be pursued. The government also plans to tackle other major issues, like advancing the country's peace process, and land reform. While there is some overlap with climate policy and fighting deforestation, there is still a risk that political attention and capital may be spread thin.

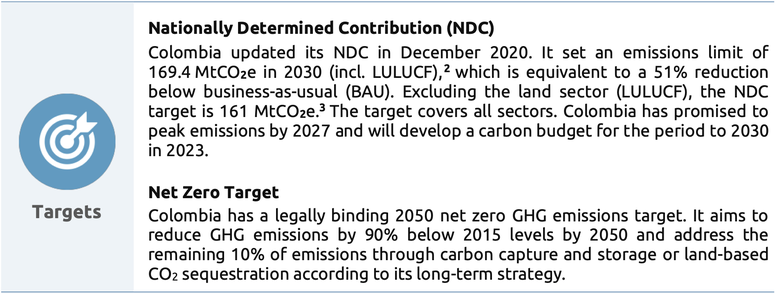

Colombia has been steadily advancing its climate policy in recent years, passing a number of important pieces of climate legislation (e.g. 2018 and 2021 climate laws and the 2019 EV law), updating its NDC target and adopting a net zero goal. While there is broad recognition across political parties of the need for climate action, the specifics on energy policy are particularly contentious. The new Energy Minister, Irene Vélez, who has been adamant that no new oil and gas exploration is needed, has faced significant and consistent criticism from some members in Congress and repeated calls for her to resign.

Colombians generally have low levels of trust in their government and public institutions and believe many to be corrupt. There have been some high-profile cases in relation to the awarding of solar and adaptation projects, which can both undermine public trust and impede implementation.

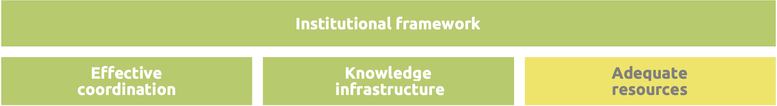

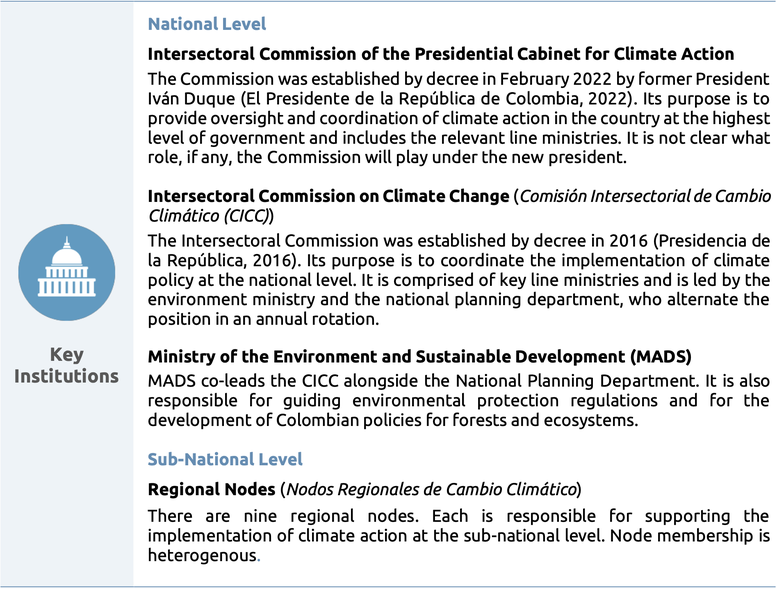

Coordination occurs through the Intersectoral Commission on Climate Change (CICC) at the national level and through nine regional nodes at the sub-national level. While it is working at the national level, as evidenced by the country’s updated NDC and adoption of its long-term strategy, the regional level faces a number of challenges, including resource constraints and low political or sectoral engagement, limiting its effectiveness. Draft regulations under consideration may address some of these issues, but further work is likely needed.

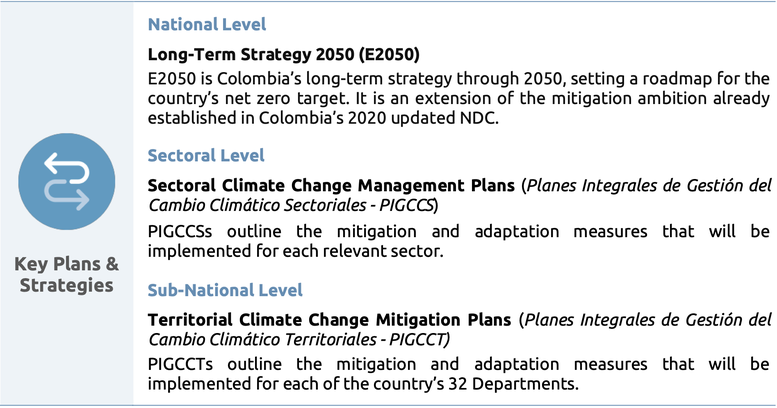

Colombia needs to work on mainstreaming climate considerations across all sectors. While the policy landscape is generally coherent, with the National Development Plan (a four-year plan adopted at the beginning of each new administration) driving broad sectoral objectives, there are many sectoral planning documents and these are not always up to date. Energy is the only sector to have updated its climate plan to align with the country’s 2050 strategy, and while the industry sector’s plan includes updated NDC measures, the others are based on the first NDC. The transport sector has not yet published its plan.

Colombia does not have an authoritative body with an explicit and clear mandate to provide zero emissions transition-related advice. Some of the technical committees of the Intersectoral Commission may fulfil some of this role. The National Climate Change Council, the permanent consultative body of the Commission, may also provide advice, though it does not yet appear to be operational. The government would benefit from reviewing its knowledge infrastructure to ensure that it is receiving the necessary advice on the transition.

Colombia has a good level of climate finance readiness. Its Financial Management Committee was established in 2016 as a sub-committee of the Intersectoral Commission (CICC) and is run by the National Planning Department. The government has worked with private sector entities to develop sub-sector specific guidelines and regulations and it has experience in a number of financial instruments, from issuing its first sovereign green bonds in 2021 to participating in the Clean Development Mechanism.

Yet, Colombia’s public and private financial flows are not yet aligned with a 1.5°C consistent pathway. Historically, government support for the fossil fuel industry has dwarfed the level spent on renewable energy incentives and climate finance more broadly. The new administration’s focus on accelerating the energy transition and its 2022 tax reforms, which will increase the effective tax burden for fossil fuel producers, will help to change this picture over time.

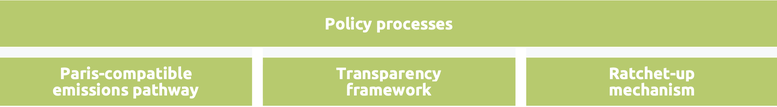

Colombia has a 2050 net zero GHG emissions target, enshrined in domestic law, and has outlined a roadmap to reach this target in its long-term strategy. Colombia needs to work on ensuring net zero considerations are incorporated into near-term policy development. As noted above, only the energy sector climate plan has been updated to incorporate the 2050 strategy. Colombia did release a net zero building sector roadmap in June 2022; however, this has not been integrated into the housing sector climate plan.

Colombia has a functioning transparency framework, though there is room for improvement. It can be difficult to access material, which may be spread across websites or reports. Nor is the information easily understandable to a non-technical audience. Progress at the sectoral level is uneven. The energy ministry is the only ministry to have released a MRV progress report.

Colombia submitted its first NDC update in 2020, but did not submit a further update in line with the 2021 Glasgow Climate Pact to ‘revisit and strengthen’ NDCs in 2022. It has also not released its first implementation and monitoring plan, assessing progress towards the current target.

Polling data suggests Colombians are worried about climate change and want more government action, though few rank climate change among their top concerns and do not see it as affecting their everyday lives. Colombia has the unfortunate distinction of being one of the most dangerous places in the world for environmental defenders, with many losing their lives each year. While consultations are held regularly, some view these as pro forma and unlikely to result in meaningful engagement.

The new government ratified the Escazú Agreement, an international treaty focused on protecting environmental defenders and enhancing public participation in environmental decision-making, as one of its first acts. Swift implementation of the Agreement is needed in order to ensure meaningful stakeholder buy-in.

Colombia’s new government is committed to ensuring a Just Transition. It is continuing with a number of processes related to the workforce and energy sectors, launched under the previous government. We are encouraged by the level of action we have seen so far, which we have rated as acceptable; however, the government will need to deliver on these processes, and not undermine the transition by approving new fossil gas developments, to maintain this score.

The fossil fuel industry and actors involved in deforestation have adversely influenced climate policy in the past. Industry influence has been diminished with the election of the new government, but it is too early to judge the extent.

This report is focused on Colombia’s national climate governance. It does not cover governance matters related to fighting deforestation, though this will be a core element of Colombia’s climate action.

Rating system

We analyse a number of different criteria of governance under four categories that cover the key enabling factors for effective climate action. We give each a rating as outlined above (very poor - poor - neutral - acceptable - advanced). For more detail on our methodology, click the link below.

Ratings and recommendations

The following section outlines the results of the analysis for each of the different categories and criteria as well as our recommendations for each category of governance.

- Continue to deliver on election promises on the energy transition and stopping deforestation

- Continue to implement measures to reduce corruption, with a focus on climate action

- Enhance the transparency of the Intersectoral Commission (by e.g. publishing meeting minutes)

- Address constraints faced by regional nodes, including adopting the draft regulations under consideration

- Get the National Climate Change Council up and running

- Review its knowledge infrastructure to ensure it is receiving the necessary advice on the transition

- Continue to redirect financial flows from the fossil fuel sector to renewable energy and address the capacity and resource constraints of line ministries and regional entities

- Align sectoral plans to the net zero target

- Improve the understandability and access of MRV reports

- Ensure all sectors publish their MRV reports

- Make public the implementation and monitoring plan for the updated NDC

- Strengthen the NDC target to be 1.5°C compatible, in line with the Glasgow Climate Pact

- Swift and comprehensive implementation of the Escazú Agreement

- Deliver on the Just Transition processes currently underway

Colombia's Climate Governance

These tables from the report give an overview and analysis of the key factors of Colombia's governance to enable effective climate action. We have looked at the country's key institutions, strategies, targets and legislation.

2 | Colombia uses global warming potential (GWP) values from the IPCC’s fifth assessment report (AR5).

3 | The figure is based on AR4 GWP values (which is the standard used by the Climate Action Tracker).

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter