Indonesia’s new climate goals: positive developments but some red flags

Indonesia's new climate goals

by Nabila Putri Salsabila and Jamie Wong

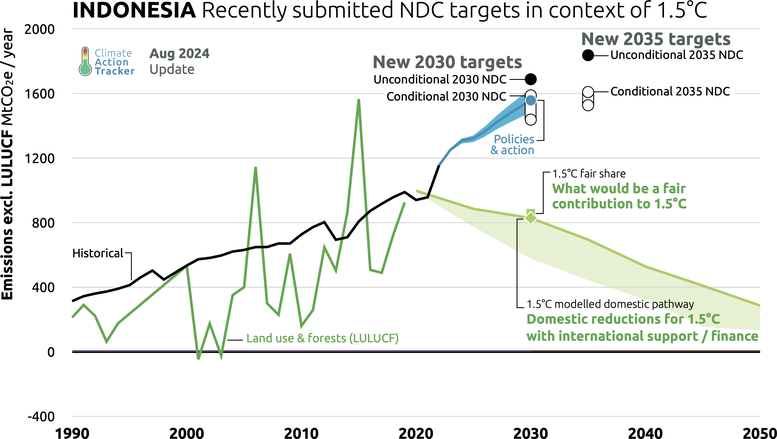

Indonesia has released a draft of its Second Nationally Determined Contribution (SNDC) for public consultation, which includes its updated 2030 targets and new 2035 climate goals. The government plans to submit the final version before COP29 in early November, where countries are expected to present their 2035 climate targets. Upon reviewing and comparing Indonesia's proposed SNDC with the Enhanced NDC (ENDC) submitted in 2022, we identified several positive developments, along with some elements that are of concern.

To evaluate Indonesia's updated climate goals, we have used the CAT’s "Guide to a good 2035 target" as a benchmark in our analysis. While this guide focuses on 2035 targets, its principles are equally applicable to strengthened 2030 targets.

Positive developments

- Slight increase in ambition – Indonesia has updated its 2030 targets, reflecting a modest improvement over its previous ENDC. The unconditional target represents the current policy scenario from the 2021 Long-Term Strategy (LTS) and is 8% lower than the previous ENDC, while conditional targets are 9-17% lower.

- NDC links interim and long-term targets – conditional NDC targets are explicitly linked to low carbon scenarios compatible with the Paris Agreement (LCCP) from the 2021 Long-Term Strategy (LTS) that targets net zero emissions by 2060. As a developing country, Indonesia's goal of achieving net zero for all greenhouse gases by 2060 can be considered ambitious and aligned with what is needed globally for 1.5°C, as outlined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Sixth Assessment Report (IPCC AR6).

- Shift from BAU to historical reference year – Indonesia’s targets are now linked to 2019 emissions instead of the previous 2010 Business as Usual (BAU) scenario.

- Expanded coverage – ENDC covers CO2, CH4, and N2O; while the SNDC expands this coverage to include HFCs. The SNDC also expands sectoral coverage to include new sub-sectors such as oceans and upstream oil and gas.

- New waste targets – the SNDC targets 'zero waste' by 2040 and near-zero waste emissions by 2050, with peak emissions expected in 2030 and a ban on new landfills after 2030.

- Just transition – the inclusion of this new subchapter in the SNDC signals a commitment to leave no one behind in transitioning to a low-carbon economy.

Negative aspects to watch for

SNDC targets are not aligned with 1.5°C!

| Scenario | 2030 Emissions (MtCO2e/year) | % Change from Baseline* in 2030 | 2035 Emissions (MtCO2e/year) | % Change from Baseline in 2035 |

|---|

| Current policy projections | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPP | 1,377 to 1,507 | +50% to +65% | N/A*** | N/A*** |

| Unconditional mitigation scenario | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPOS | 1,688 | +84% | 1,837 | +101% |

| Fair share** (1.5°C) | 817 | -11% | N/A*** | N/A*** |

| Conditional mitigation scenarios | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCCP-low | 1,438 | +57% | 1,527 | +67% |

| LCCP-high | 1,588 | +73% | 1,609 | +76% |

| MDP** (1.5°C) | 771 | -16% | 647 | -29% |

Note:

*the baseline year is 2019, and total emissions for 2019 (excluding LULUCF) are 916 MtCO2e

**all values are expressed in GWP from the IPCC AR5. MDP and fair share values are converted from AR4 to AR5

***the fair share emissions range for 2035 is not available

****Note that there is a mistake in the SNDC where the total minus forestry emissions does not match the sum of non-forestry sectors. We assume the mistake is in the total and not the sectoral emissions targets.

Unambitious unconditional target that peaks emissions in 2050

- The unconditional target, which aligns with the LTS current policy scenario, reflects minimal to no climate action. It is higher than the current policy scenario ranges and allows emissions to only peak in 2050, at approximately double the 2019 levels.

Limited action before 2030 and huge reliance on steep reductions after 2035 to meet net zero target

- The conditional NDC targets indicate limited action before 2030, with emissions peaking in 2035 followed by a steep decline through 2060. These extreme reduction pathways are inefficient and carry a significant risk of not being achieved without disruptive policy, substantial international support and favourable external factors.

- The conditional NDC pathways are not aligned with the CAT’s global least-cost 1.5°C pathways that require much lower emissions in 2030/2035 and more gradual reductions over the century. Delaying significant climate action until 2035 risks an overshoot of the 1.5°C target, even with strong 2035 targets and aggressive carbon dioxide removal (CDR) efforts.

Overreliance on carbon sinks from land and marine ecosystems

- Heavy reliance on Land Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) despite high historical emissions – Indonesia aims for the LULUCF sector to become a net sink by 2035 in the unconditional NDC and by 2025 in the conditional LCCP scenarios. Given the short timeline and Indonesia’s historically high LULUCF emissions, achieving these targets may be challenging.

- No separate targets for LULUCF and CDR removals – this lack of distinction raises concerns about transparency. For more details, see our net zero blog.

- Heavy reliance on LULUCF can divert attention and efforts from necessary emissions reductions in other critical sectors like energy and industry. Relying on LULUCF sinks brings risks and uncertainties because:

- LULUCF emissions are subject to large fluctuations and uncertainties, making it difficult to accurately project and account for emissions reductions.

- Lack of permanence of removals – carbon stored in the land system is vulnerable to being released back into the atmosphere due to natural disturbances or shifts in land management practices.

- Ocean-based carbon sequestration should not be used to offset emissions in other sectors. While critical for climate change mitigation and adaptation, relying on coastal and marine ecosystems would undermine efforts to limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C due to:

- Dilution of overall mitigation ambition – lessons from the LULUCF sector reveal how countries have used creative accounting to offset fossil fuel emissions.

- Lack of permanence – climate change impacts, such as sea level rise and ocean warming, may damage these ecosystems and reverse carbon sequestration over time.

- Huge data uncertainty – carbon flows in coastal ecosystems are highly uncertain and difficult to measure accurately.

Other red flags

- No explicit commitment to fully phase-out coal, as required by the Presidential Regulation 122/2022 which sets out a 2050 phase-out date for coal power.

- False solutions – the SNDC and forthcoming New and Renewable Energy Bill continue to include false solutions such as "clean coal", coal-derived technologies, nuclear power, gas as a "cleaner" fuel, and Carbon Capture, Utilisation, and Storage (CCUS).

- Bioenergy plans conflict with the FOLU net sink target – strategy for biomass co-firing, biodiesel and bioethanol could drive further deforestation and jeopardise plans for the LULUCF sector to become a net sink by 2030.

- No explicit commitment to halt deforestation – the SNDC draft lacks details on deforestation quota, which are crucial for achieving the FOLU net sink target by 2030.

- Lacks details on climate finance needs – this is critical for effective planning and securing both international support and national budget allocations for climate initiatives.

- Lacks procedural transparency – the absence of a full-text draft and the brief 1.5-week public consultation period hinders meaningful engagement and scrutiny of assumptions.

Way forward

- Incorporate climate justice. Indonesia's SNDC should integrate metrics rooted in recognitive, procedural, distributive, and restorative justice, ensuring that vulnerable groups are central in policy development and implementation.

- Reaffirm commitment to climate goals. As Indonesia approaches a government transition in October, it is crucial for the new administration to reaffirm its commitment to climate goals. This transition presents a pivotal moment that could significantly shape the direction of Indonesia's future climate policies.

- Develop credible plans and policies aligned with its ambitious net zero pathway. To achieve its ambitious net zero emissions goal by 2060, Indonesia must collaborate with supporting countries to carefully design and implement credible climate action that will drive substantial emissions reductions by 2030, 2035, and beyond.

Notes: For a more comprehensive set of policy recommendations, we encourage readers to review the analysis by IESR, our partner organisation.

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter