What do governments need to deliver in 2022?

Post-Glasgow momentum

The dust is settling on COP26 with analyses flying in on the good, the bad, and the “best we could hope for”. But COP26 is not the end of the story and to bring 1.5°C back from the edge we need to see momentum on real emissions reductions pick up in 2022. What does this momentum look like?

The CAT’s new rating system allows us to see which governments have set ambitious targets, which ones have put the policies in place to meet them, and the ones who need to step up on climate finance. Across the board, the most important step is that governments put new policies in place and provide appropriate financial support where needed. With clear signals on coal coming out of COP26, transitions away from all fossil fuels, including oil and fossil gas, need to accelerate and action enhanced across all sectors.

All governments should bring something new to the table, although with different expectations for different countries.

Major rehaul of NDC targets needed

An alarming number of NDCs—including many from the world’s major emitters—still fall well short of what a fair contribution would be, and are far from sufficient to get on a track toward decarbonising the economy consistent with the 1.5°C Paris Agreement temperature limit.

A number of countries we track—accounting for over 15% of global emissions—submitted an updated NDC without strengthening ambition, contrary to the Paris Agreement’s requirement for progression. Many NDCs do not reflect the reality on the ground—for example, that renewables are increasingly a cheaper option than fossil fuels.

Here’s looking at you Australia, Brazil, Russia, and Mexico.

Closer to the mark, but need more work

Several governments have come forward with stronger NDC targets in the last year that could lead to substantial emissions reductions. However, most of these targets are still not rated as Paris Agreement compatible, so there’s room for improvement.

Those that should strengthen their targets further include the EU, the USA, Japan, Switzerland, Canada, and Norway. South Korea announced a new NDC at COP26 but it is still far from being compatible with the Paris Agreement. India and China also need to increase their ambition levels, as both countries would meet the new targets submitted or announced at COP26 with current policies.

Even the UK, rated as 1.5°C compatible under its domestic target, should bolster its plans to meet its fair share. And many developing countries could flag greater ambition through submitting stronger targets conditional on international support.

Finance is key to unlocking mitigation potential

Developed country governments need to urgently strengthen their support for mitigation overseas. In many countries, current policies and targets show high potential for further mitigation. To halve global emissions in the next decade, we will need to shift the curve in all countries. Doing so in a fair and equitable manner will require increased financial support from developed countries.

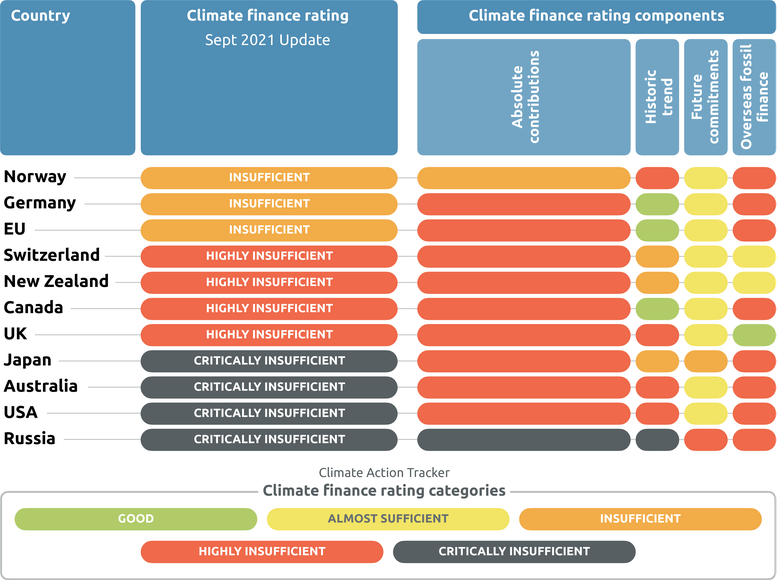

Under the CAT’s new rating method, we show that all the developed countries we assess fall far short of meeting their fair share contribution. In the next year they need to step up their climate finance contributions even further. A domestic target that meets global least-cost mitigation scenarios is not a sufficient overall contribution to meeting the Paris Agreement.

All of the countries we assess on their provision of climate finance fall well short of the mark, but some clearly stand out from the crowd. Norway, Germany, and the EU are still insufficient, but comparatively better, as their overall contribution in the last five years has been closer to their fair share. Switzerland, New Zealand, Canada, and the UK are highly insufficient, while Japan, Australia, the USA and Russia are critically insufficient.

Announcements of new climate finance made before and during COP26—including those by the USA and New Zealand—are welcome but not yet enough to boost the mitigation finance ratings we released in September (see figure below) which give a stronger weight to finance actually delivered.

The commitment by many governments to no longer finance fossil fuels abroad is a major break-through and needs to be implemented swiftly and thoroughly. Governments now also need to take the next step and commit to ending fossil fuel funding and subsidies at home.

South Africa’s USD 8.5bn finance package for the retirement of coal plants, the deployment of renewable energy, and managing a just transition

At COP26, South Africa announced an agreement with several donors (France, Germany, UK, USA, EU) on a USD 8.5bn package of grants and concessional finance over three to five years to accelerate the retirement of coal plants and the deployment of renewable energy. This agreement builds on a country-led, donor-supported process by the South African government, putting a distinct focus on a Just Transition, including the retraining and support of coal workers.

While more details on the package will be needed for an assessment of the potential impact on a Just Transition away from coal, this process could become a ‘blueprint’ for other recipient and donor countries to provide climate finance.

Update NDCs in line with sectoral initiatives

Many governments signed up to new sectoral initiatives announced at COP26, including on methane, clean cars and vans, coal, deforestation, and oil and gas exploration.

If their signatures under the initiatives mean more action than their current NDCs, these countries could improve their NDCs to take the new action into account. This could include the new coal phase-out intentions for the Philippines and Indonesia, and the deforestation claims of Indonesia and Brazil (noting that Indonesia later backed out of the forests declaration).

But the initiatives are really designed to put those governments on the spot that have NOT yet signed. These countries should reconsider and, upon signing, they could also update their NDCs. For example, China, India, and Russia on methane; or Germany, Japan, the USA, China, and France on clean transport; or indeed the USA, Australia, Russia, China, India, Thailand, and Morocco on coal. While the alliance to end oil and gas production is still nascent, developed countries and major oil and gas producers such as the USA, Canada, Norway, Australia, and the UK should in particular lead the way.

NDCs need more clarity

Some NDCs are difficult to quantify and could have a better rating if more clarity were provided, or if the government committed to the more stringent end of a range. Governments setting relative targets as reductions under a “business as usual” (BAU) scenario, such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Iran, Mexico, and Thailand could strengthen their NDC in 2022 by phrasing them in absolute terms or as reductions below a historical year, as done by Chile, Singapore, and Colombia. Turkey ratified the Paris Agreement shortly ahead of COP26 and should now update its NDC, which is based on an inflated BAU scenario, exaggerating its reduction targets. Saudi Arabia’s 2021 NDC mentions the use of a BAU scenario but has not yet communicated what that is.

Implementation on the ground

Improvements in targets are essential, but these would mean little in the absence of policies and measures for their implementation. The CAT estimates that policies and action currently fall short of targets by 2–6 GtCO2e in 2030 and of a 1.5°C pathway by 25–29 GtCO2e. To bring down 2030 emissions, all governments need to put new and strengthened policies in place.

Governments should take their signature of the sector initiatives of COP26 seriously and follow through with implementation. In some cases, this is would be a clear deviation from current practices. For example, Brazil signed the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forest and Land Use, which aims to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030, but the deforested area in Brazil has grown in recent years back up to levels not seen since 2005. These statistics were not released until the end of the conference.

Many governments still see coal as a major energy source (and export) well beyond 2030, including Australia, Indonesia, China, India, Colombia, and Morocco. Others, such as Viet Nam, Chile, or Germany, are making a move away from coal but are, to a varying extent, relying on gas—still a fossil fuel, and not compatible with 1.5°C. These countries should consider moving directly to renewable energy, a cheaper alternative that doesn’t trash the climate.

Halving emissions by 2030 will mean action in all sectors. We’ve seen some promising signs in the uptake of electric vehicles in the last few years, but this is only the start, and progress in other sectors is lacking. Constructing zero carbon buildings, ramping up deep renovation rates, scaling up public transport, innovative industrial processes, moving away from oil and gas production, and changing the way we feed ourselves are all off-track for a 1.5 compatible world. Even hopes from recently renewed commitments to reduce deforestation were dampened shortly after COP with news of increased deforestation rates in Brazil in 2021.

Again, enhancing international climate finance is critical for ramping up this implementation and ensuring that that global decarbonisation is achieved in a just and fair way.

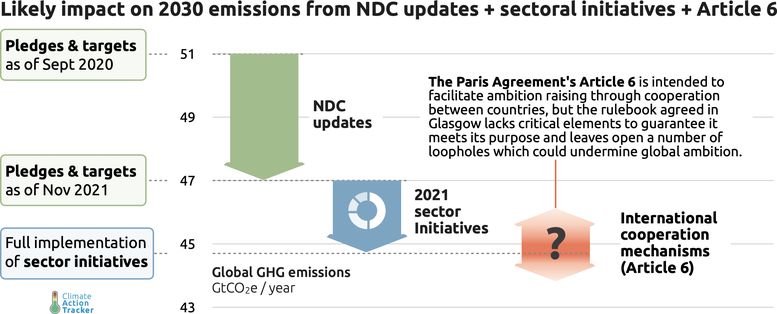

Article 6 mechanisms should only be used to target high hanging fruit

Glasgow saw governments finally reach agreement on the rulebook for the Article 6 ambition raising mechanisms. Whilst the text offers clarity in some areas, it is sparse in the all-important details, leaving open a number of loopholes that risk undermining, rather than increasing global ambition to tackle climate change.

The compromise agreement allows carryover of up to 0.3 GtCO2e of Kyoto era units and enables all Clean Development Mechanism projects to continue crediting, which could generate a further 2.8 GtCO2e worth of credits.

Most, and possibly all, of the combined three billion possible credits from projects accredited under the Kyoto regime are likely to represent emission reductions that will happen anyway and should not be used towards NDC targets. Perhaps more critically, the carryover of legacy, low-cost credits and activities sets a very poor precedent for the development of new projects, whose ambition level must be far higher than the low hanging fruit projects targeted through Kyoto-era flexibility mechanisms, to avoid disincentivising ambition.

Governments who have put their own houses in order—through commitment to sufficiently ambitious NDCs and the fulfilment of their fair share of international climate finance targets—could potentially support further ambition raising by using Article 6 mechanisms to go beyond this, targeting only high hanging fruit projects that are truly inaccessible to the host countries.

For governments whose NDCs and climate finance contributions are not 1.5°C Paris Agreement compatible (and today none are), the use of Article 6 mechanisms is likely to offer an escape hatch to urgently ramping up domestic decarbonisation. In addition, the prospect to be able to sell allowances that go beyond the NDC is an incentive for low ambition.

Unambitious use of the option to trade mitigation outcomes could widen the emissions gap. Current arrangements made by Switzerland appear to fall into this category.

Much to do and little time to waste

With 1.5°C hanging on a knife edge and the credibility of the Paris Agreement under a cloud following the very limited success in Glasgow of closing the 2030 emissions gap, there is an enormous amount to do in 2022 by the time the COP reconvenes in Egypt.

Keeping 1.5°C alive will need everybody to bring something new to the table before COP27. Who’s going to take the lead?

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter