Summary

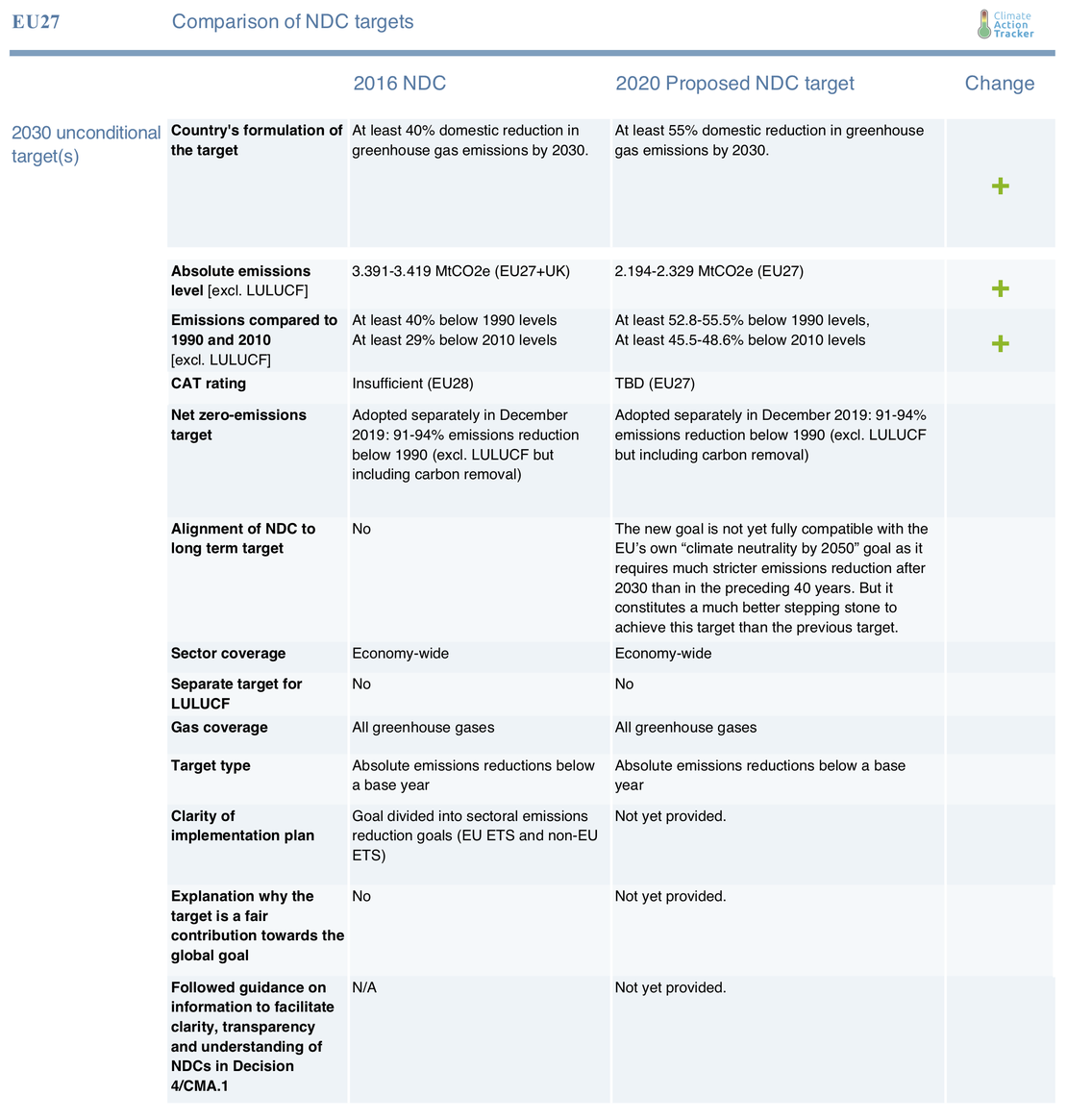

On 11 December 2020, the heads of the EU Member States agreed on a stronger 2030 domestic emissions target of “at least 55%” net reduction below 1990 levels. This goal will be submitted as part of the EU’s NDC by the end of the year. This target is an improvement of the EU’s previous target of “at least 40%”. Changes in the treatment of the land sector slightly weaken this target compared to its predecessor, resulting in an emissions reduction of 52.8% below 1990 levels excluding LULUCF.

While this stronger 2030 target is a step in the right direction, it is still not enough to make the EU compatible with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5˚C goal. Domestic emissions reductions of between 58% and 70% are needed to make the EU’s effort compatible with the Paris Agreement. The adoption of the European Parliament’s proposal of a 60% (excl. LULUCF) target would have aligned the EU to the Paris Agreement. The EU will also need to provide further support to developing countries for emissions reductions abroad to ensure it is contributing its fair share of the global mitigation burden.

The gap between the new goal and what is needed to be compatible with the Paris Agreement can be closed by adopting more ambitious policy measures than required by translating this goal to sectoral emissions reduction targets. This possibility of ratcheting up the 2030 goal through more ambitious domestic climate action needs to be reflected in the “Fit for 55” package of measures that the European Commission will propose in the first half of 2021.

CAT analysis of NDC announcement

On 11 December 2020, the EU heads of state agreed to increase the EU’s NDC target of reducing emissions to “at least 55%” net below 1990 levels by 2030. This target will replace the “at least 40%” emissions reduction target for the same period adopted in October 2014 and submitted in the EU’s first NDC. The new target is defined as “net”. This means that the target also includes emissions sinks in the land use and forestry (LULUCF) sector. These sinks are projected to be around 30 MtCO2eq lower in 2030 than in 1990 which weakens this target by around 2%.

Depending on the way this target is implemented, this could result in emissions in 2030 amounting to between 2,324 – 2,329 MtCO2eq. or 52.8% below 1990 levels (excl. LULUCF). Should extra-EU aviation and maritime sectors also be included in this target, domestic emissions would have to decrease to 2,194 MtCO2eq or 55.5% below 1990 levels (excl. LULUCF).

Due to methodological complexities and data issues stemming from the UK’s decision to leave the EU, the CAT is not currently able to provide an exact fair-share rating for the new EU27 goal. Upon resolution of these methodological requirements, we will rate this NDC.

The new target sets a more appropriate starting point towards achieving the goal of emissions neutrality by 2050 than the preceding one. However, it is still not enough to make EU compatible with the Paris Agreement. Domestic emissions reductions by between 58% and 70% are needed to make the EU’s effort compatible with the Paris Agreement. The European Parliament has already called for emissions reduction by 60% (excluding LULUCF), and its adoption would have aligned the EU’s target to the Paris Agreement. According to some studies, emissions reductions by 65% are possible with existing technologies.

Stating “at least” indicates that the EU can go beyond that by adopting more ambitious policy measures. This was the case for the preceding 2030 “at least 40%” emissions reductions goal, which was complemented with renewable energy and energy efficiency goals that would result in emissions reduction by up to 48%. The Renewable Energy Directive adopted in 2018 explicitly required a reassessment of the renewable energy goal with a view to increasing it in the case of substantial cost reductions, decreased energy demand or new international commitments.

This possibility of ratcheting up the new 2030 target through more ambitious domestic climate action should be reflected in the package of measures the European Commission will propose in the first half of 2021. The ratcheting up possibility included in the Renewable Energy Directive (which itself will be revised in 2021) should be included in other pieces of legislation. This legislation will be changed based on the Commission’s proposals in the “fit for 55%” package to be tabled in June 2021, to reflect the higher emissions reduction goal just adopted. This concerns especially the Emissions Trading System Directive that should allow for substantially decreasing the emissions cap, for example, to reflect accelerated coal phase out, or tightening emissions performance standards for cars and vans should the share of electric vehicles increase much faster than expected. This goal can also be strengthened by including extra-EU aviation and maritime emissions.

At the same time, the EU should ensure that it is meeting its emissions reduction goal in all areas. The recently released emissions projections indicate that under policies and measures introduced and planned by member states before March 2020 the EU would only reduce its emissions by 36% below 1990 in 2030. The ambition reflected in the National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) that each Member State submitted throughout 2019 and 2020 would result in emissions reductions in 2030 of 41% below 1990. These projections do not consider any potential economic implications and resulting emissions reduction induced by COVID-19 pandemic. However, these COVID-19 related impacts might only be temporary and will not trigger the transformative change needed to fully decarbonise the EU economy by the middle of the century.

In the framework of the post-COVID-19 recovery the EU has also agreed to devote at least 30% of its 2021–2027 Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) and the Next Generation EU Recovery Fund (NGEU) resulting in almost €600 billion to be spent on climate action. This funding could trigger and leverage additional public and private funding to accelerate decarbonisation. The EU should also ensure that proceeds from carbon pricing are used to decarbonise the EU’s economy and avoid carbon lock-ins, e.g. from development of natural gas infrastructure.

The adoption of the more ambitious emissions reduction target, even if not yet consistent with the Paris Agreement, is a step in the right direction. However, much more can and needs to be done to not only make the EU’s climate effort compatible with the Paris Agreement but also decarbonisation of the European economy a vehicle of economic recovery from the COVID-19 induced recession.

Links

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter