Current Policy Projections

Overview

Under current policies, annual emissions from all sectors (excluding LULUCF) are still projected to grow significantly, namely by about 56% above 2010 levels by 2030, reaching about 490 MtCO2 in 2030. This is equal to doubling 1990 emissions levels, and means missing its NDC values by a large margin.

Our analysis of current policies is based on the mitigation scenarios underlying the third National Communication of Argentina to the UNFCCC (Secretariat of Environment and Sustainable Development, 2015). Additional policy scenarios, assuming a full implementation of the renewable targets and additional energy efficiency measures, shown in our analysis are based on the Energy Scenarios from the Ministry of Energy (Ministry of Energy and Mining Argentina, 2018b).

Depending on these variables Argentina might overachieve its unconditional NDC target or miss it by a wide margin, unless additional action is taken. In the last months, a push by parts of the government towards the exploitation of national oil and natural gas resources has threatened progress in this direction (see more detail in the section on energy supply below).

Argentina is going through a severe economic crisis, which also has led to changes in the structure of ministries with the objective to decrease government spending. Included in these changes are departments dealing with climate change: the former energy ministry and the environment ministry both became secretariats, reporting to the Ministry of Economics and the president’s office, respectively. Similarly, the Ministry of Agriculture is now a Secretariat of the Ministry of Production (Government of Argentina, 2018). It is unclear whether the structural change will have an impact on climate policy. The direct impact of decreased economic activity on emissions is also still unclear. The GDP projections underlying the current policies projections do not consider the current recession. The scenarios do not provide total GPD growth. The growth of the production value is estimated around 3% for most sectors (Government of Argentina, 2015b).

In December 2017, Argentina adopted a carbon tax covering all fossil fuels sold in Argentina, based on a price of 10 USD/tCO2e (FARN, 2017; Ministerío de Justicia y Derechos Humanos, 2017). The impact of the tax on emissions has not yet been quantified. This comprehensive tax is a very good first step in the right direction. Some international sources suggest significantly higher carbon prices are required for Paris compatibility (at least USD40–80/tCO2 by 2020 and USD50–100/tCO2 by 2030 (Stiglitz et al., 2017). Our policy projections, as well as the new scenarios from the Ministry of Environment, do not yet specifically reflect the recently implemented carbon tax, and no studies exist quantifying the impact. An earlier proposal in Argentina included a carbon price of 25 USD/tCO2e but the final decision was for a much weaker tax. National NGOs have criticised the final rule as too unambitious and merely a tool to align with international activities to increase the chances for accession to the OECD, rather than an instrument to safeguard the environment (FARN, 2017). The law distributes the tax revenues to different areas, most not directly linked to climate change or environmental issues (Ministerío de Justicia y Derechos Humanos, 2017).

Energy supply

The government of President Mauricio Macri has introduced various policies that can potentially reduce emissions of the energy sector, including a renewable energy law and a biofuels law (Government of Argentina, 2015b & Government of Argentina, 2016b). The renewable energy law (Law 27191), published at the end of 2015, aims to increase the share of renewables (including hydro smaller than 50 MW) in total power generation to 20% by 2025 (Government of Argentina, 2015a). An auctioning scheme—RenovAr—supports this target. Up to now, three auctioning rounds were held (RenovAr 1, 1.5 and 2), leading to contracting of 4.7 GW of renewable electricity (Ministry of Energy and Mining Argentina, 2018a).

In September 2018, the Argentinian government announced a fourth round (RenovAr 3), under which it will tender 0.4 GW of renewable electricity installations. RenovAr 3 will focus on small-scale renewables, with a capacity up to 0.01 GW per installation to be connected to the medium-voltage grid (Pozzo, 2018). This limitation in size results from problems with grid capacities in the high-voltage grid(ibid).

Concerns about grid access have been raised, potentially causing a delay in the grid connection of the contracted capacities and making additional bidding rounds more difficult to realise. The national grid operator CAMESSA has recognised this issue already and is working on the extension of the electricity grid (Télam, 2017; CAMMESA, 2018). However, at this point in time CAT could not find an indication of a clear timeline, and the CAMMESA documentation specifically states that no legal claims can be made based on a delay in access to the electricity grid (CAMMESA, 2018). A positive effect of the focus on small-scale is the opening of the market to private stakeholders (Pozzo, 2018).

The increasing focus of the parts of the government on exploiting national oil and natural gas resources is a development potentially endangering the expansion of renewable energy, and risking increasing emissions and significant stranded assets. The Secretariat of Energy is promoting the “Vaca Muerta” shale gas reserve as a source of cheap oil and gas for national consumption, but also for export (Secretaría de Energía Argentina, 2018).

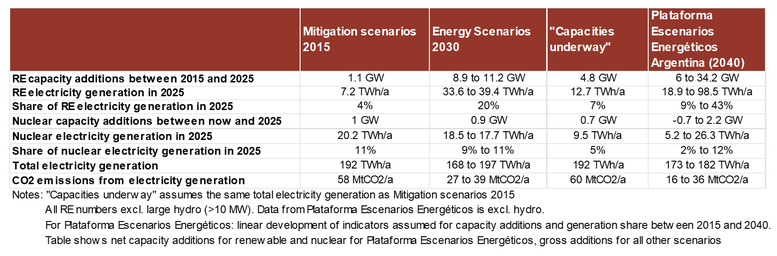

Available projections for the energy sector vary significantly in their assumptions on energy split and demand. The following table compares indicators for the year 2025 from three scenarios for the electricity sector:

- The Mitigation Scenarios 2015, which the Argentinian government used as the basis for its 3rd National Communication (Secretariat of Environment and Sustainable Development, 2015).

- The Energy Scenarios 2030, which the former Ministry of Energy and Mining published in early 2018 to provide additional scenarios under different assumptions (Ministry of Energy and Mining Argentina, 2018b).

- The “Capacities underway” scenario, which CAT developed based on currently installed capacities and projects in the pipeline. This includes the RE capacities tendered under RenovAr and the Candu nuclear reactor. For large hydro, we assume capacity additions as in the Mitigation Scenarios 2015.

- The scenarios from the “Plataforma Escenarios Energéticos 2040”, a non-government initiative under which different modelling groups provide alternative energy futures for Argentina up to the year 2040 (Beljansky et al., 2018). The “Escenarios Energéticos” do not present a projection of what will likely happen; the exercise aims at showing how different developments in the energy sector could look and creating a discourse over the potential outcomes of such developments.

The Mitigation Scenarios 2015 are the starting point for our current policy projections, in which we then adjust the renewable energy capacities to follow the “capacity underway” scenario. The Energy Scenarios 2030 are the basis for the additional policies scenario range, and the “Escenarios Energéticos“ are shown as comparison.

In comparison to the “Mitigation Scenarios 2015”, the “Capacities underway”-scenario shows higher electricity generation from renewable sources, but lower nuclear generation based on today’ status of new nuclear plants. The “Capacities underway” scenario result in similar emission levels from the electricity sector as the “Mitigation Scenarios 2015”. The electricity related emissions from the Energy Scenarios 2030 are much lower, given higher shares of renewables and an overall lower electricity demand at the lower end of the scenario range.

While the Energy Scenarios 2030 represent a detailed representation of possible future planning for the energy sector, additional actions need to be taken to achieve the share of low-carbon electricity supply assumed by the scenarios. One important area of improvement is the above-mentioned grid integration: the energy scenarios assume a large amount of additional wind capacity in Patagonia (Ministry of Energy and Mining Argentina, 2018b). Investments in the electricity grid will be critical to transport the electricity generated to urban centres. With the focus of the Secretariat of Energy on oil and gas exploitation and distribution, reaching the renewable energy penetration indicated in the Energy Scenarios 2030 seems less likely than in our previous assessment in May 2018.

The results from the “Escenarios Energéticos” vary widely depending on the modelling group elaborating the results. Overall, their share of renewable energy is significantly higher in 2025 than other scenarios, assuming a linear increase of capacities (data is only available for the year 2040) (Beljansky et al., 2018).

Industry

Between 1990 and 2014, direct emissions from industry in Argentina rose from 24.2 MtCO2e to 37.5 MtCO2e, a 55% increase, according to the national inventory (Ministry of Environment Argentina, 2017). Over this period, activity-related GHG emissions increased by 74%, while energy-related emissions increased by 42.5%. In 2014, the total contribution of Argentina’s industry sector (37.5 MtCO2e) to total national emissions (including LULUCF) was around 10.2%. The largest share of direct emissions was produced by the minerals industry (6.7 MtCO2eq). Emissions from industry are projected to almost double by 2030 (Secretariat of Environment and Sustainable Development, 2015).

In 2015, the Argentinean government promulgated the Renewable Energy Law 27.191 to foster the use of renewable energies in the industry sector. This law mandates all large-scale electricity users to comply with the renewable energy targets i.e 20% of national electricity consumption by 2025. This policy will not have an impact on direct emissions from the industry sector, but will support emissions reductions of the electricity generation.

To boost energy efficiency, the Argentinean government developed the Energy Efficiency Fund in 2009. One of the objectives of this fund is to improve energy efficiency among small and medium enterprises (SMEs) through energy audits. However, while on the one hand the government aims to promote energy management systems for industrial companies through subsidies (Ministry of Energy and Mining, 2018), it keeps subsidising on the other hand electricity consumption for large-scale users (Ministry of Energy and Mining, Ministry of Industry, 2017).

Transport

In 2014, emissions from the buildings sector in Argentina represented 15% (~57 MtCO2e) of Argentina’s GHG emissions (including LULUCF) according to the national inventory. According to the Mitigation Scenarios 2015, emissions from transport will increase by 50% in the coming decades from 55 MtCO2e/a in 2012 to 80 MtCO2e/a in 2030 (Secretariat of Environment and Sustainable Development, 2015).

For fuel switch, the biofuels law (Decree 543/16) adopted in March 2016 requires a minimum 12% of bioethanol blend in transport fuels from 2016. Calculating the impact of this policy, we find this implies a minor improvement of emissions compared to the Mitigation Scenarios 2015, even if we assume that the production of biofuels is carbon neutral, which is disputable (DeCicco et al., 2016).

Buildings

In 2014, emissions from the buildings sector in Argentina represented 9% (~34 MtCO2eq) of Argentina’s GHG emissions (including LULUCF) according to the national inventory. They grew by 73% between 1990 and 2014 and are projected to increase by 85% by 2030 (Secretariat of Environment and Sustainable Development, 2015). Residential buildings played a major role in this increase, growing from 14 MtCO2eq in 1990 to 28 MtCO2eq in 2014, while emissions from commercial and institutional buildings remained stable at around 5 MtCO2e/yr.

Improving energy efficiency is Argentina’s main strategy to reduce emissions in the buildings sector. The National Programme for a Rational and Efficient Use of Energy (PRONUREE) launched in 2007 will ultimately lead to the implementation of energy labelling for residential buildings (Ministerio de Energía y Minería Argentina, 2018). Several pilot programs set up by the Argentinean government are currently underway in a few cities such as in the city of Rosario since October 2017.

Public buildings and infrastructures are also targeted by the government. The Efficient Public Lighting Plan (PLAE) launched in 2017 aims to reduce emissions from street lighting by 50%. Argentina also set out various measures to improve energy efficiency in public buildings through the “Programa de Ahorro y Eficiencia Energética en Edificios Públicos” (Ministerio de Energía y Minería Argentina, 2007).

Agriculture

Agricultural emissions in Argentina (~110 MtCO2e/a in 2014 according to the national inventory) contribute a share of about 30% of total national emissions (incl. LULUCF). Agricultural products are an important part of Argentina’s exports, and the activities as well as related emissions are set to increase further, reaching about 160 MtCO2e/a by 2030 according to the Mitigation Scenarios 2015.

There is no clear policy framework to support emissions reductions in the agricultural sector. A few measures and policies promoting more sustainable agriculture, with climate benefits, do however exist: The National Programme for Good Agricultural Practices in Fruit and Vegetable Products mandates the promotion of agriculture that preserves natural resources (water, soil and energy), and through Resolution 120/2011, Argentina established the Programme for Smart Agriculture. It supports implementation and further distribution of smart agricultural practices and technologies, as well as research and development (Ministry of Agriculture Livestock and Fishing, n.d.). Climate smart agricultural practices are in some cases already used by farmers, particular no-tillage is wide spread (World Bank, CIAT, & CATIE, 2014). The “Ley del Bosque Nativo” (see section “Forestry”) also includes incentives for sustainable agro-forestry.

Considering the high level of methane emissions, combined with the associated deforestation this activity has caused, the agriculture and cattle-ranching sector offers great potential for Argentina to constrain its emissions. This big potential is confirmed by a document published by the Ministry of Agroindustry in 2017, which examines a number of possible measures for mitigating climate change in the agricultural sector, which could improve the productivity of the sector and also reduce land use changes and deforestation linked to agricultural practices and by increasing carbon sinks, including sinks in the soil (Andrade et al., 2017).

Forestry

Net GHG emissions from LULUCF in Argentina (46 MtCO2e/a in 2014 according to the national inventory) contribute a share of about 12% of total national emissions. We have observed a clear trend in decreasing LULUCF emissions since 2010 as a result mostly of the implementation of the 2007 Native Forests law (“Ley de Bosque Nativo”).

The Native Forests law aims at controlling the reduction of native forest surface, aiming at achieving net-zero change in forest areas. The law sets minimum budgets to be spent on forest protection, established a capacity building scheme and requirements for provinces to comprehensively monitor and track forests areas. In the late 1990s, Argentina implemented the law for investments in afforestation and preventing forest degradation. According to Argentina’s Second Biennial Update Report, this law has led to an additional 31 thousand hectares of forest area per year on average (Government of Argentina, 2017).

In the Mitigation Scenarios 2015, the Argentinian government expects emissions from the sector to decrease further, from about 90 MtCO2e in 2012 to 37 MtCO2e in 2030. IIASA calculates emissions remain roughly at 2010 levels, at slightly above 100 MtCO2e/a (Kuramochi et al., 2017). For comparison: For calculating absolute emissions levels excl. LULUCF resulting from the NDC, we assume that the share of the LULUCF emissions in 2030 will be similar to the share of these emissions in the NDC’s BAU scenario, at 77 MtCO2e in 2030.

Waste

Between 1990 and 2014, Argentina’s waste emissions increased by about 76%. The increase of those emissions by 2030 is projected to reach 60% (Secretariat of Environment and Sustainable Development, 2015). In 2014, emissions from waste accounted for 3.8% (14 MtCO₂e) of Argentina’s GHG emissions – against 2.7% of overall emissions in 1990 (Ministry of Environment Argentina, 2017).

In 2005, Argentina implemented a National Strategy for the Management of Urban Solid Waste (ENGIRSU). Its objectives are to reduce, reuse and recycle waste as well as to avoid landfills in order to protect the environment (Ministerio de Salud y Ambiente Argentina, 2005). However, the implementation of norms regarding waste management falls within the jurisdiction of Provinces, which can lead to disparities in its enforcement. To date, no policies have been implemented in Argentina to directly reduce GHG emissions from waste.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter