Policies & action

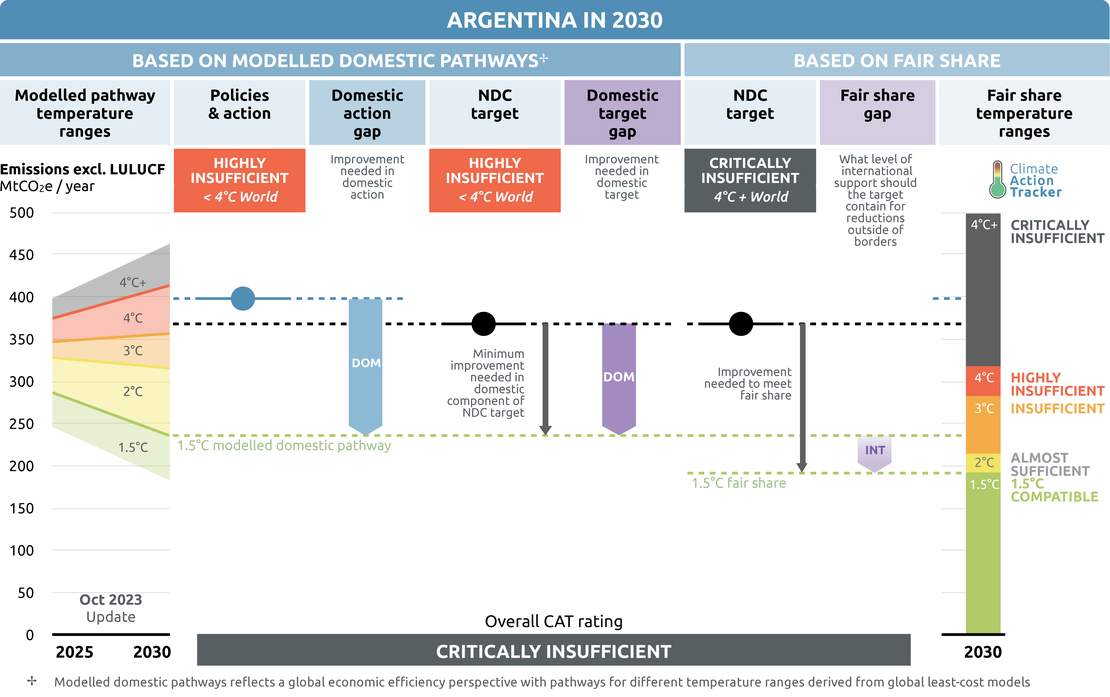

We rate Argentina’s policies and actions as “Highly insufficient” when compared with modelled domestic emissions pathways. The “Highly insufficient” rating indicates that Argentina’s climate policies and action in 2030 need substantial improvements to be consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C. If all countries were to follow Argentina’s approach, warming would reach over 3°C and up to 4°C.

Argentina’s policies and action rating compared to modelled domestic pathways is now lower than in our previous assessment due to an update in our modelled domestic pathways to the pathways assessed in the AR6. This latest evidence shows that Argentina needs to cut emissions faster to align with 1.5°C.

Argentina’s current policies would lead to warming exceeding 4°C when compared to its fair share contribution. Whether Argentina will achieve its NDC depends mostly on how it develops its energy sector. The sector’s development will be directly affected by the economic recovery after the current crisis, the expansion of fossil fuel infrastructure and renewables, and future energy demand.

Argentina’s policies and action also remain inadequate to achieve its NDC target. The CAT estimates that under current policies, Argentina will miss its target by 30 MtCO2e.

In 2021, emissions in Argentina rebounded back to 2019 levels after a sharp drop in 2020 due to COVID-19. This puts Argentina’s projections under current policies at approximately 8% above its 2030 target. Under the planned policies scenario, if Argentina were to implement additional policies to scale-up low carbon energy sources and reduce energy demand, it could reach and potentially overshoot its NDC target. However, to be consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C, Argentina would additionally need to develop more ambitious policies, especially to stop deforestation, and reduce livestock-related emissions.

With the general elections in October 2023, Argentina has not yet seen a candidate with a strong push for ambitious climate policies. Following a year of severe drought and economic instability for the country, political platforms are focusing on restoring fiscal balance and stable growth, as well as curbing soaring levels of inflation. As part of Argentina’s strategy to reduce energy imports and lower pressure on foreign currency reserves, the current government has focused mostly on developing the Vaca Muerta shale fields. However, candidates could adopt a different strategy and invest resources in decreasing dependence on oil and gas by pushing for electrification and development of renewables.

The current administration has shifted Argentina’s energy policies from a focus on developing renewables towards fossil gas and nuclear power. One of the cornerstones of Argentina’s current strategy is the shale oil and gas field of Vaca Muerta. In 2022, high international fossil fuel prices, resulting from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, rekindled interest in Vaca Muerta after two years of low oil and gas prices, which caused production to decline and future developments to be put on hold. As a response, the government fast-tracked a previously mothballed project to build a pipeline connecting Vaca Muerta with the national gas network to enable a substantial ramp-up of production.

In January 2023, the government started negotiating contracts with oil and gas producers at Vaca Muerta to ensure the future pipeline will work at capacity (Government of Argentina, 2022h). In June 2023, the pipeline was finished ahead of schedule and started operations. It is expected to carry 11 m3/d during 2023, and to reach 22 m3/d in 2024 (Diamante, 2023). This has the potential to prevent Argentina from meeting its climate targets through higher upstream energy emissions as well as lock-in effects from fossil fuel infrastructure.

In December 2022, the government published its new National Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Plan until 2030 (Government of Argentina, 2022g). This strategy was published shortly after Argentina submitted its Long-term strategy to the UNFCCC, and it reiterates both Argentina’s NDC and LTS targets, as well as expanding on many of the measures presented in Argentina’s Fourth BUR earlier in 2022.

The strategy includes detailed information on Argentina’s climate measures and targets covering all major sectors. Some highlights of this strategy include targets for the decarbonisation of the transport sector, incentives to increase energy efficiency in buildings, and measures to reduce food loss and waste. This strategy, however, does not include any new renewable energy targets or measures, and it does not include any significant measures to reduce emissions from the land sector, especially from livestock.

In July 2022, the government agreed to implement a segmented tariff scheme to make subsidies less regressive, and possibly save up to USD 500min subsidy spending in 2023. The new finance minister, Sergio Massa, announced shortly after his appointment that the subsidy scheme would further include a consumption cap of 400 kWh per household per month, beyond which all subsidies would be removed (Diamante, 2022). In January 2023, the government announced it would cap energy bill increases at ~USD 2/month per household. This could significantly limit the impact of the subsidy reform on energy consumption (Government of Argentina, 2023b).

Policy overview

Under current policies, total emissions (excluding LULUCF) are still projected to grow significantly after 2021, namely by about 25% above 2010 levels by 2030, reaching about 398 MtCO2 in 2030 (excl. LULUCF). This is means Argentina is on track to miss its NDC target by 8%.

Our analysis of current policies is based on projections developed by the National University of Central Buenos Aires (UNICEN) (Blanco & Keesler, 2022). These projections include relevant policy developments up to 2022.

UNICEN additionally models a series of carbon neutrality scenarios for Argentina’s energy sector that show Argentina could get on track in reaching its NDC target by decarbonising its power grid towards 2040, as well as by banning sales of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles by 2050, developing green hydrogen for industry, and increasing energy efficiency and electrification in the buildings sector. If Argentina were to implement these measures, it could further reduce its emissions by 14% below current policy projection levels.

In July 2019, Argentina was the first country in Latin America to declare a climate emergency. While the draft declaration included 15 points and an action plan, the final text was reduced to only two paragraphs and is considered to have symbolic character (Himitian, 2019). In December 2019, the Congress passed a law on climate change (ley n.° 27520) that seeks to establish minimum budgets for the adequate management of climate change, including for the design and implementation of mitigation and adaptation policies, actions, instruments, and strategies.

Sectoral pledges

In Glasgow, a number of sectoral initiatives were launched to accelerate climate action on methane, the coal exit, 100% EVs and forests. At most, these initiatives may close the 2030 emissions gap by around 9% - or 2.2 GtCO2e, though assessing what is new and what is already covered by existing NDC targets is challenging.

For methane, signatories agreed to cut emissions in all sectors by 30% globally over the next decade. The coal exit initiative seeks to transition away from unabated coal power by the 2030s or 2040s and to cease building new coal plants. Signatories of the 100% EVs declaration agreed that 100% of new car and van sales in 2040 should be electric vehicles, 2035 for leading markets, and on forests, leaders agreed “to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030”.

NDCs should be updated to include these sectoral initiatives if they’re not already covered by existing NDC targets. As with all targets, implementation of the necessary policies and measures is critical to ensuring that these sectoral objectives are actually achieved.

| ARGENTINA | Signed? | Included in NDC? | Taking action to achieve? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methane | Yes | Unclear | No |

| Coal exit | No | Not applicable | No |

| Electric vehicles | No | Not applicable | No |

| Forestry | Yes | Unclear | No |

| Beyond oil and gas | No | Not applicable | No |

- Methane pledge: Argentina is one of the 95 countries that signed the methane pledge. While Argentina’s carbon emissions have almost doubled since 1990, its methane emissions have remained relatively stable with emissions only roughly 10% above 1990 levels in 2021 (Government of Argentina, 2022c; Gütschow & Pflüger, 2023). Nevertheless, methane still accounts for 29% of all national GHG emissions in terms of global warming potential, above the global average of around 20% (Global Methane Initiative, 2022). While methane is covered in Argentina’s NDC target, the NDC contains no specific targets nor actions aimed at reducing methane emissions. Current methane emissions are 100.7 MtCO2e (in AR4 GWP), with two thirds related to livestock. Meeting the 30% methane reduction target would mean a 28.5 MtCO2e reduction by 2030.

- Coal exit: Argentina did not sign the Coal Exit agreement. The country’s electricity generation matrix is dominated by fossil gas and large hydro, with coal contributed only around 1.4% in 2019. Argentina has neither plans to phase-out coal, nor a pipeline to develop more capacity.

- 100% EVs: Argentina has no plans to phase-out the sale of ICE vehicles and did not sign the agreement. Transport emissions in the country are significant, representing 27% of energy-related emissions. The uptake of EVs in the country is very slow: only 260 vehicles were sold in 2022. However, sales of hybrid vehicles are increasing substantially, with around 7850 sales in 2022. This already represents a significant year-on-year increase compared to 2021, and there is the expectations that sales will really take off as the government sets out financial incentives to support EVs (Della Vecchia, 2023) .

- Forestry: Argentina signed the forestry pledge at COP26 in 2022. The forest sector is a source of emissions in Argentina, with deforestation being responsible for around 47 MtCO2e in 2018 (Government of Argentina, 2022c). The country has sectoral plans in place to reduce deforestation, and a system to provide incentives for producers through ecosystem services payments. However, local organisations report that these policies are being under-funded and not properly enforced (Escobar, 2021).

- Beyond oil and gas: Argentina has no plans to stop the exploration and production of fossil fuels. On the contrary, new offshore exploration activities are planned for 2023, and Argentina keeps providing incentives for companies operating at the Vaca Muerta gas field (Government of Argentina, 2022d, 2022e).

Energy supply

Argentina’s energy sector is its biggest source of GHG emissions, reaching 193 MtCO2eq in 2018 (54% of the total). Total energy supply increased 81% between 1990 and 2021, and fossil fuels still account for around 89%, mostly gas (50%) and oil (36%). Electricity generation roughly tripled in the period 1990-2021, reaching 150 TWh in 2021. While electricity generation is still dominated by fossil fuels, especially gas (58%), in the period 2015-2020, wind and solar PV have taken off, reaching 10% of total generation in 2020, from roughly 0% in 2015 (IEA, 2022).

In recent years, Argentina has centred its energy sector strategy around the exploitation of abundant gas reserves in the “Vaca Muerta” formation as a source of cheap oil and gas for national consumption and exports (Secretaría de Energía Argentina, 2018). However, the long-term development of Vaca Muerta remains uncertain even in the context of high oil and gas prices due to increasing political and economic instability and associated risks for investors.

In January 2018, Argentina implemented a carbon tax covering most liquid and solid fuels sold in the country at 5 USD/tCO2e. The tax is estimated to cover 20% of the country’s GHG emissions. Fossil gas is exempted from the tax, as is CNG and fuel consumption in international aviation and shipping, as well as the export of these fuels. The tax is a first step in the right direction. Yet, significantly higher carbon prices are required for Paris Agreement compatibility (at least USD 40–80/tCO2 by 2020 and USD 50–100/tCO2 by 2030 (Stiglitz et al., 2017)).

Oil and gas

During the first half of 2022, the topic of energy subsidies was a focal point of debate within the governing coalition. In July, the government agreed to implement a segmented tariff scheme to make subsidies less regressive, and possibly save up to USD 500m in subsidy spending in 2023 (Rivas Molina, 2022). The new finance minister, Sergio Massa, announced shortly after his appointment that the subsidy scheme would further include a consumption cap of 400 kWh per household per month, beyond which all subsidies would be removed (Diamante, 2022). In January 2023, the government announced it would cap energy bill increases at USD~2/month per household. This could significantly limit the impact of the subsidy reform on energy consumption (Government of Argentina, 2023b).

In 2022, high international fossil fuel prices, resulting from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, rekindled interest in Vaca Muerta after two years of low oil and gas prices, which caused production in Vaca Muerta to decline and future developments to be put on hold. According to the government, production of shale oil reached its highest level since 2011 in January 2023, with 289,000 barrels of oil per day, and shale gas reached 50 Mm3 per day. This represents a 13% increase in oil production compared to last year’s peak of 254,000 barrels, and a decrease of gas production of 34% compared to last year’s peak of 76 Mm3 (Government of Argentina, 2022e, 2023c).

High international fossil fuel prices also spurred the government to fast-track in 2022 a previously mothballed project to build a pipeline connecting Vaca Muerta with the national gas network to enable a substantial ramp-up of production. These efforts to increase domestic gas production are outlined in the Gas.Ar Plan, published in November 2020, which announces the target of producing 30,000 Mm3 of fossil gas in four years. This plan includes incentives and benefits for companies looking to produce fossil gas and aims to replace imports and save the government USD 2.6bn in fiscal spending and over USD 9bn in foreign currency (Government of Argentina, 2020c). In January 2023, the government was already negotiating contracts with oil and gas producers at Vaca Muerta to ensure the future pipeline was working at capacity (Government of Argentina, 2022h). In June 2023, the pipeline was finished ahead of schedule and started operations. It is expected to carry 11 m3/d during 2023, and to reach 22 m3/d in 2024 (Diamante, 2023).

Additionally, new conventional oil field discoveries off the coast of Namibia have sparked exploration plans off the coast of Buenos Aires. This is because both continents were much closer at the time of the formation of those reserves. First explorations have started in 2023 with the expectation of finding up to one billion barrels of oil (Government of Argentina, 2022d). This would significantly increase Argentina’s reserves, currently at 2.5 billion barrels (World Population Review, 2022).

These developments will most likely impact total emissions in the country through increases in fugitive emissions, as well as creating lock-in of fossil infrastructure and disincentives for a deeper transformation of the energy sector. Additionally, an increased dependence on internationally traded goods can increase Argentina’s vulnerability to external shocks. The increased production of fossil fuels could also lead to higher energy consumption. As part of its push towards domestic oil and gas production, the government also plans to set out measures to reduce flaring and leakage, but so far does not provide information on specific measures or targets (Government of Argentina, 2022g).

The government has made a commitment to the IMF that it will increase its foreign currency reserves and reduce primary fiscal deficit. Replacing gas imports with domestic production is part of the plan to achieve the first, while reducing energy subsidies is key to achieve the second.

Electricity supply

Argentina’s current government has shifted the country’s focus from renewables towards gas and nuclear power. In July 2022, as part of its nuclear plan, the government announced a deal with Chinese manufacturers to start construction of a new nuclear plant with a capacity of 1.2GW before the end of 2022 and plans for the development of an additional plant. The project will cost USD 8.3 billion and will be 85% Chinese financed (Government of Argentina, 2022b), however, it is currently at a standstill due to financing disagreements with its Chinese funders (Bernhard, 2022). The government also plans to retrofit at least two simple-cycle gas power plants to combined-cycle to improve efficiency and add 420 MW of generation capacity (Government of Argentina, 2022g).

Although nuclear electricity generation does not directly emit CO2, the CAT doesn’t see nuclear as the solution to the climate crisis due to its risks such as nuclear accidents and proliferation, high and increasing costs compared to alternatives such as renewables, long construction times, incompatibility with a flexible supply of electricity from wind and solar, its vulnerability to heat waves, and the creation of nuclear waste.

The former government of President Mauricio Macri introduced various policies that could potentially reduce emissions of the energy sector, including a renewable energy law and a biofuels law (Government of Argentina, 2015b & Government of Argentina, 2016b). The renewable energy law (Law 27.191), published at the end of 2015, aimed to incentivise the development of renewable electricity generation and foster the use of renewable energy across sectors. The law establishes a renewable energy target of a 20% share of renewables (including hydro smaller than 50 MW) in electricity consumption by the end of 2025 (Government of Argentina, 2015). This target is still considered in Argentina’s latest Climate Mitigation and Adaptation Strategy of 2022 (Government of Argentina, 2022g), but Argentina is currently not on track to meet it, with around 13% of power generation in 2021 coming from renewables excl. large hydro (IRENA, 2023).

An auctioning scheme—RenovAr—is in place to support this target. Up to now, four auctioning rounds have been held (RenovAr 1, 1.5, 2 and 3), leading to the contracting of 4.7 GW of renewable electricity (Morais, 2019). Furthermore, a long-term market for renewable energy (MATER), established through Resolution 281-E/2017, encourages bilateral agreements between energy producers and large-scale consumers. The resolution prioritises the dispatch of renewable generation in case of curtailments due to transmission network congestions (Ministry of Energy and Mining, 2017). Together with PPAs, these three instruments combined have led to the commissioning of 6.5 GW of renewable power in Argentina by 2019. For the period up to 2030, Argentina plans to develop 2.6 GW of modern renewables on top of the current 4.7 GW, and 2GW of large hydro on top of the current 10.4GW (Government of Argentina, 2022g; IRENA, 2023).

However, the current administration has halted previous plans to develop renewable energy, including the fifth round of the RenovAr scheme. The tightening of capital controls by President Fernandez, the renegotiation of foreign debt with the IMF, the political risk, the limited access to credit and grid limitations are also discouraging investors and slowing down the growth of the renewable industry (Energía Estratégica, 2020).

Concerns about grid limitations had been raised before RenovAr 3, potentially causing a delay in the grid connection of the contracted capacities and making additional auction rounds more difficult to realise. The national grid operator CAMMESA has recognised this issue and is planning on the extension of the electricity grid (CAMMESA, 2018; Télam, 2017). So far the only measure taken to alleviate this bottleneck has been to make contract conditions more flexible for capacities contracted during previous RenovAr rounds for projects that will not be completed. However, Argentina’s 2022 climate strategy includes a target to add ~4200 km of new extra-high voltage lines by 2030 as well as several transformer stations which should enable a higher development of renewables (Government of Argentina, 2022g).

Announced in COP 26, the Australian firm Fortescue will invest USD 8.4bn in the Argentinian province of Rio Negro to develop green hydrogen. The first phase of the project will generate 650MW and include a wind farm and a port for transportation. It will initially be destined for export, but capacity can be expanded to 8GW in future phases, enabling the dedication of some production for the domestic market. This project fits into a provincial plan to produce 2.2 Mt by 2030 (Garcia Pastormerlo, 2021). In its 2022 climate strategy, the government also included plans to prepare a National Hydrogen Strategy with more clear milestones for Argentina’s domestic hydrogen industry (Government of Argentina, 2022g).

Agriculture

Agricultural emissions in Argentina were 113 MtCO2e in 2018, accounting for roughly one third of Argentina’s total emissions (excl. LULUCF), and 7% of total energy demand (Government of Argentina, 2022c). The agricultural sector is a major economic powerhouse of the country, and especially to its export market. Key commodities produced in Argentina are soybeans, wheat, maize, and cattle. In total, agricultural commodities represented 71% of Argentinian exports in 2020, and USD 38.6 billion in value.

Despite the high emissions in the sector, Argentina’s national action plan for agriculture and climate change only includes three concrete measures planned for the agriculture, livestock and forestry sector up to 2030, including afforestation (area from 1.38 million to 2 million hectares between 2018 and 2030), crop rotation (increasing the area under cereals (wheat, maize) and decreasing the area under oilseeds (soybeans, sunflower)) and biomass utilisation for energy generation, particularly for off-grid use (Secretaria de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable, 2019).

As part of its 2022 climate strategy, the Argentinian government has set out some additional livestock-related measures. These include an increase in GHG-efficiency of livestock of 5% until 2030 (without a clear baseline), and the promotion of silvopastoral systems through REDD+ payments. However, it remains unlikely that these measures will significantly bring down livestock-related emissions (Government of Argentina, 2022g). A recent study analyses the potential of supply-side mitigation options to reduce emissions in the agriculture and land use sector including feed optimisation, livestock health monitoring, the use of cover crops and crop rotation, synthetic fertiliser management and the use of silvopastoral systems. It found that the combined technical mitigation potential for these measures was of around 28.1 MtCO2e, or around 14% below the reference scenario in 2030. The gap to the sectoral net zero scenario, that is, the amount that Argentina would need to further reduce to be on track to a net zero AFOLU sector was of around 103 MtCO2e in 2030 (Gonzales-Zuñiga et al., 2022).

This shows the need for transformation in the sector: even implementing best practices and increasing the efficiency of agricultural production, the sectoral gap to a 1.5˚C -compatible emissions pathway is very large. Argentina will need a deeper transformation of its wider food system if it is to keep its emissions in line with limiting warming to 1.5˚C.

Transport

In 2018, emissions from the transport sector in Argentina represented 16% (~51 MtCO2e) of Argentina’s GHG emissions (excluding LULUCF) according to the Fourth Biennial Update Report, and approximately 31% of energy demand.

In its 2022 climate strategy, the government included several EV-related targets. These include the installation of over 86,000 charging stations, 2,500 fast-charging stations, and targets to increase the sales of light- and heavy-duty EVs, as well as a target to replace 100% of public administration vehicles with EVs or hybrid vehicles by 2030 (around 146,000 vehicles). The government is also incentivising the conversion of private vehicles to compressed natural gas (CNG) (Government of Argentina, 2022g).

The uptake of EVs remains low in Argentina, but it is now picking up due to incentive policies. In 2021, the Argentinian Association of Automobile Dealerships reported 5,871 new sales of low-emissions mobility light-duty passenger vehicles, out of which 99% where hybrid cars and only 1% plug-in EVs (Bloomberg Linea, 2022). In 2022, sales increased by 33% reaching 7,849 new sales, out of which 97% were hybrid and 3% pure electric (Della Vecchia, 2023).

In its 2022 climate strategy, the government includes measures to support the development of rail infrastructure, including adding 83 km of electric train tracks by 2026 (Government of Argentina, 2022g).

In its 2022 climate strategy, the government disclosed its biofuels targets, which are to increase bioethanol blending to 15% in 2025, and to meet 20% of total fuel demand with biofuels by 2030. The government also plans to support second generation biofuels and aims at reaching 2Mt of organic waste to be used for biofuels by 2028 (Government of Argentina, 2022g).

This contrasts with its current mandates which reduced biodiesel blending mandates from 10% to 5%, with the option of being further reduced to 3% if biofuel input prices increase so much that they significantly impact final fuel prices for consumers. A recent study has calculated that this reduction can lead to increasing cumulative emissions by 7.9-11.7 MtCO2e in the period 2021-2030 (Magnasco & Caratori, 2021). However, a reduction in the production of first-gen biofuels can also have positive effects in land related emissions, reducing the pressure to expand agricultural lands and demand for the commodities used as feedstock (Rulli et al., 2016).

In March 2021, the government also introduced a new mandatory light-duty vehicle label to reflect fuel efficiency and emissions in all new vehicles under 3.500 kg.

Since 2008, the government has incentivised the use of public transport in large urban areas through the development of Bus Rapid Transit Systems (BRTS). As of 2020, 18 BRTS are in place, with a goal to reach 20 by 2030 (Government of Argentina, 2022c).

Argentina’s average share of emissions from LULUCF over the past 20 years are more than 20% of the country’s total emissions. Argentina should work toward reducing emissions from LULUCF, particularly reducing deforestation and to preserve and enhance land sinks.

LULUCF emissions in Argentina were around 39.3 MtCO2e in 2018 according to its Fourth Biennial Update Report (Government of Argentina, 2022c), accounting for 10% of national GHG emissions. LULUCF emissions have been on a downward trend partially thanks to the implementation of the 2007 Native Forests Law (Law 26.331). They decreased by 65% in 2018 compared to 2007 levels but remain a significant source of emissions in Argentina.

Argentina has around 54 million hectares of native forests, as well as 1.3 million hectares of cultivated forests. According to its fourth BUR, in 2018 some 187,000 hectares were lost due to the expansion of agricultural land, forest fires, and overexploitation of forest resources (Government of Argentina, 2022c). The government acknowledges that some of this land clearing is illegal, and the better enforcement of forestry regulations is needed.

The Native Forests Law aims at controlling the reduction of native forest surface, focused on achieving net-zero change in forest areas. The law sets minimum budgets to be spent on forest protection, established a capacity building scheme and requirements for provinces to comprehensively monitor and track forest areas. It also establishes the National Fund for Enriching and Conserving Native Forests that disburses funds to provinces that protect native forests (Law 26331, 2007).

As early as the late 1990s, Argentina implemented Law 25.080 to promote investments in afforestation and preventing forest degradation (Ley 25.080, 1999). According to Argentina’s fourth Biennial Update Report, this law, which has been amended by Law 26.432 in 2008, has contributed to a total of 1.3 million hectares of forest area, with a target of 1.6 million in 2030 (Government of Argentina, 2022c). However, independent sources claim that the program has been de-funded and ecosystem services payments have been greatly decreased in real terms, and its effectiveness to continue to support afforestation and preservation is at risk (Escobar, 2021).

In 2018, and in the frame of the UN REDD+ program, Argentina submitted its National Action Plan on Forests and Climate Change (PANByCC), which includes a target of 27MtCO2eq reduction from land use emissions by 2030 (UNREDD, 2022).

Alongside the implementation of its PANByCC, Argentina launched its ForestAr 2030 initiative, which aims to develop a broad stakeholder dialogue and strategy to conserve natural forests and to deliver on the country’s commitment to reducing climate change while achieving other sustainable development benefits. In the context of this initiative, the government created the National Plan for the Restauration of Native Forests through Resolution 267/2019, which seeks to restore 20 million hectares of native forest per year by 2030 (Resolución 267/2019, 2019).

A recent study shows that for Argentina’s AFOLU sector to get close to carbon neutrality, the LULUCF sector would need to become a net emissions sink as fast as possible, and reach around -138 MtCO2e per year just to neutralise emissions from agriculture by 2050 (Frank et al., 2023). To achieve this, Argentina would need to set out stronger forestry policies, including ambitious targets and well-designed implementation and enforcement mechanisms, as well as improved coordination with subnational governments.

Industry

Between 1990 and 2018, direct emissions from industry in Argentina rose from 29.7 MtCO2e to 54.6 MtCO2e, i.e. by 86%, according to the Fourth Biennial Update Report (Government of Argentina, 2022c). Over this period, activity-related GHG emissions increased by 157%, while energy-related emissions increased by 58%. In 2018, the total contribution of Argentina’s industry sector (54.6 MtCO2e) to total national emissions (excluding LULUCF) was around 16% and represented 23% of total energy demand.

The biggest subsectors by production value are food and beverage manufacturing (31%), construction (14%) and manufacture of chemical substances and products (12%). The industrial sector is also the biggest consumer of fossilgas after thermoelectric generation plants. However, most process-related emissions stem from steel and cement production.

The Renewable Energy Law 27.191, adopted in 2015, also specifically fosters the use of renewable energy in the industry sector. It mandates all large-scale electricity users to comply with national renewable energy targets, i.e. 20% of national electricity consumption by 2025. Users can either do so by purchasing electricity from the wholesale market or by signing third-party power purchase agreements with independent renewable energy producers. (Ministry of Energy and Mining, 2017).

The government also seeks to promote energy management systems for industrial companies. In 2018, the Ministry of Energy passed Provision 3/2018, which establishes that companies benefitting from reduced electricity prices under Resolution 1-E/2017 have to implement the ISO norm 50001 on energy management systems, including the development of an energy management action plan, energy performance targets and indicators to monitor progress (Ministry of Energy and Mining, 2018). In its 2022 climate strategy, the government reinstates its existing plans and measures for reducing energy consumption in businesses (Government of Argentina, 2022g).

Buildings

In 2018, emissions from the buildings sector in Argentina represented 8% (~28 MtCO2eq) of Argentina’s GHG emissions (excluding LULUCF) according to Fourth Biennial Update Report. They grew by 60% between 1990 and 2018. Residential buildings played a major role in this increase, almost doubling from 13.5 MtCO2e in 1990 to 24 MtCO2e in 2018, while emissions from commercial and institutional buildings remained stable at around 4 MtCO2e/yr. In 2018, buildings represented around 25% of energy demand.

As a response to the COVID-19 crisis, the government has allocated ARS 100 billion (USD 1.4 billion approximately) for the construction and refurbishment of buildings, schools and hotels. However, the measure is not accompanied by sustainability and energy efficiency guidelines (Government of Argentina, 2020a).

Since 2017, several pilot programmes set up by the Argentinean government have been underway in a few cities such as in the city of Rosario, aiming at validating the efficiency norms to subsequently apply them as public polices at the national level (Climate Action Tracker, 2019). Targeting infrastructure more directly, the Efficient Public Lighting Plan (PLAE), launched in 2017, aims to reduce emissions from street lighting by 50% and it is still developing new projects as of January 2023 (Government of Argentina, 2022f).

In 2017, the government adopted Law 27.424 to promote the use of renewables in the building sector. The Law encourages small-scale electricity users (residential and commercial) to produce their own energy from renewable resources. This law encourages self-consumption of electricity through the introduction of net-metering (Ley 27424 - Régimen de Fomento a La Generación Distribuida de Energía Renovable Integrada a La Red Eléctrica Pública, 2017). Argentina’s 2022 climate strategy also includes targets for solar water heating in residential housing, as well as the installation of four million square metres of solar panels in businesses (Government of Argentina, 2022g).

In 2018, the government adopted an energy efficiency labelling scheme for residential housing, aiming at improving access to information for consumers and incentivise efficiency improvements. Until 2022, this system was run by provinces, with slightly different standards being applied. Starting in 2023 the programme will be handled by the national government, with the overarching aim of reaching six million households by 2030 (Government of Argentina, 2023a).

In its 2022 climate strategy, the government also lists several measures aimed at reducing energy consumption from household appliances. These measures include credit lines to upgrade fridges, heat pumps, lighting, and others. It also includes quantitative targets for specific appliances, such as 9.6 million fridges replaced by 2030, and 7.8 million heat pumps installed (Government of Argentina, 2022g).

Waste

Between 1990 and 2018, Argentina’s waste emissions more than doubled, accounting for 6% (19.3 MtCO2e) of Argentina’s total GHG emissions in 2018. Waste production is in the order of 1kg per person per day in Argentina (Government of Argentina, 2022c).

In 2021, the Environment Ministry released resolution 290/2021 establishing the National Programme to Strengthen the Circular Economy. This policy aims at improving waste collection and treatment systems, reducing waste and increasing recycling rates. To date, no policies have been implemented in Argentina to directly reduce GHG emissions from waste.

According to Argentina’s Fourth Biennial Update Report, there has been progress on segmented waste collection and treatment. Big urban centres have also implemented systems to capture and store or destroy methane from waste, while in the rest of the country, solid urban waste is still disposed of in open landfills without sanitary treatment.

Argentina’s 2022 climate strategy also includes measures and targets for the waste sector. In particular, it aims at eradicating open landfills by 2030, and to reduce food loss by 10-30%, and waste by 5-10% by 2025 below 2015 levels. These targets are also part of Argentina’s National Plan for Food Loss and Waste Reduction (Government of Argentina, 2022g).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter