Policies & action

The CAT policies and action emissions scenario is based on the weaker and stronger recovery scenarios published by the Australian Government which consider a number of current policies in addition to differences in economic activity to account for the unknown impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The government claims its high technology uptake scenario meets the 2030 NDC target. However, this scenario does not reflect current policy, but it is based on a number of non-policy related assumptions such as higher energy efficiency rates and renewable uptake internationally. Australia will need to implement a range of additional policies to reach its 2030 target. Australia’s current policies result in emissions 7% below 2005 levels by 2030 (excluding LULUCF), whereas the 1.5°C modelled domestic pathway is 47% below 2005 by 2030 (excluding LULUCF).

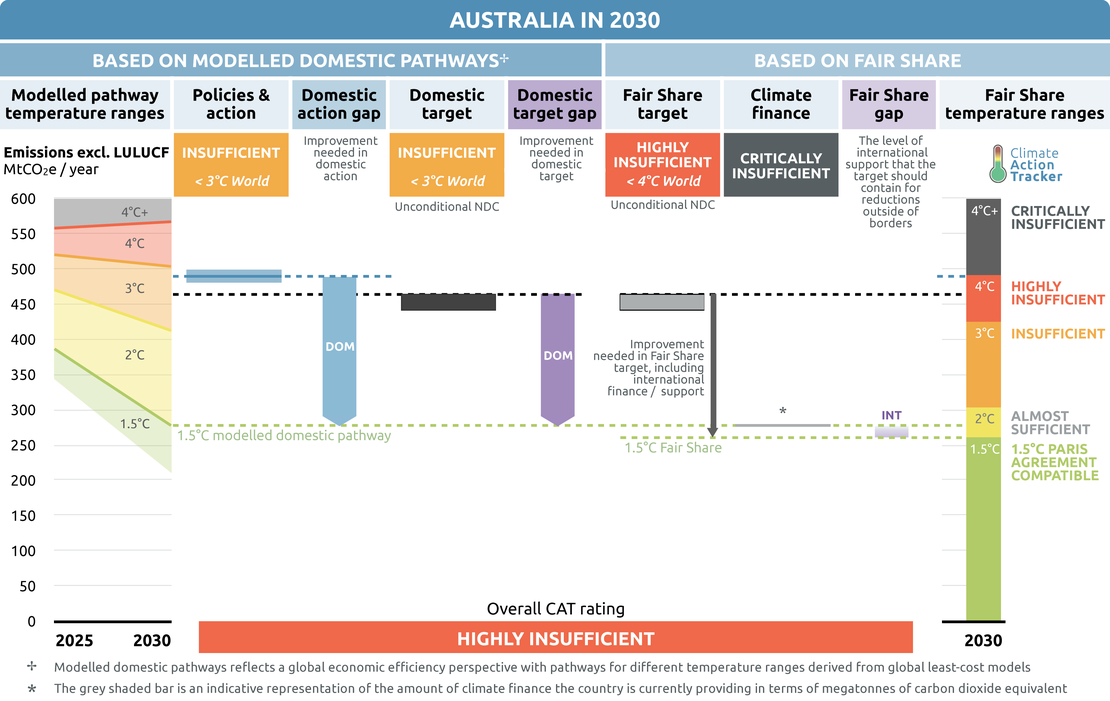

The CAT rates Australia’s policies and action as “Insufficient”.

The policies and action emissions scenario include the following policies:

- Technology Investment Roadmap and Low Emissions Technology Statement:

The Statement supports the fossil fuel industry as it lists CCS and hydrogen (without a green focus) as priority areas. CCS and fossil fuel hydrogen support can prolong the life of aging fossil fuel fleets in the energy system. Other priorities are energy storage, low carbon materials (steel and aluminium), and soil carbon.

- Climate Solutions Fund (also known as Emissions Reductions Fund or ERF):

The ERF is a reverse auction mechanism designed to reduce emissions, through organisations and companies voluntarily abating greenhouse gases for carbon credits purchased by the government.

- Large-scale Renewable Energy Target (expired in 2020) and the Small-scale Renewable Energy Scheme.

- National energy efficiency measures.

- National Energy Productivity Plan.

- Initiatives by ARENA and CEFC.

- The National Food Waste Strategy.

- Legislated phase-down of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs).

- Energy Performance, refrigeration and air conditioning measures.

- State-based actions, as effective climate policy is more evident at the state and territory level, such as through state-based energy efficiency measure, state renewable energy targets and state waste policies.

The policies and action emissions scenario does not include:

- The government’s ramp up of the “gas-fired recovery” in the 2021 Budget. The Federal Budget supports gas infrastructure projects, such as extending gas pipelines, import terminals, storage facilities and a gas supply hub.

- In April 2021, the Prime Minister pledged AUD 275m for hydrogen hubs and AUD 263.9m directed towards CCS.

- New Future Fuels Strategy discussion paper which fails to provide electric vehicle subsidies or set a phase out date for fossil fuel new car sales as other countries have done.

- Government grants to scale up the capacity of diesel reserves.

These recent developments will likely raise the policies and action emissions pathway.

The “Insufficient” rating indicates that Australia’s policies and action trajectory in 2030 needs substantial improvements to be consistent with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C temperature limit. If all countries were to follow Australia’s approach, warming would reach over 2°C and up to 3°C.

Further information on how the CAT rates countries (against modelled domestic pathways and fair share) can be found here.

Policy overview

Australia’s policies and action fall short of the emissions reductions required to meet the 2030 target put forward in its NDC. Australia’s total GHG emissions excluding LULUCF are projected to decrease to between 481 to 498 MtCO2e by 2030. This is equivalent to a decrease in emissions from 2005 levels (excluding LULUCF) of only 5% to 8% by 2030.

COVID-19 Response

The Australian government has not initiated a green recovery. The Federal Budget for 2021-22 aims to “secure Australia’s recovery” by allocating AUD 58.6m on gas infrastructure and new gas supply with no new support for renewable energy or electric vehicles (Australian Government, 2021). Federal and state governments provided AUD 10.3bn on spending and tax breaks for the fossil fuel industry in 2020-21 (Campbell et al., 2021). AUD 8.3bn has been committed to subsidising the gas extraction, coal power stations, coal rail, ports, CSS and other fossil fuel support. The gas-led focus of government planning is unlikely to change in the 2022 election as both Labour and the Coalition support the gas industry (Sydney Morning Herald, 2021).

As an initial response to COVID-19, the government appointed a National COVID-19 Commission which has now concluded. The Commission included mining industry stakeholders and produced recommendations for a gas-led recovery (Mazengarb, 2020; Parkinson, 2020). The Commission recommended the government to underwrite new gas pipeline infrastructure, as well as domestic gas supply and for state governments to subsidise gas-fired power generation (Murphy, 2020).

The government plans to replace retiring fossil fuels with more fossil fuels, despite battery and renewable energy hub plans. The Federal Budget 2021-22 allocates AUD 30 million for a new gas fired power station and AUD 24.9 million for new gas fired power plants to become hydrogen ready.

The Government announced a public funded AUD 600m Kurri Kurri 660 MW gas fired power plant in Hunter Valley NSW to replace the Liddell coal station (Gooley, 2021). Local businesses have objected to the government funded gas plans (Mazengarb, 2021b). Energy Australia proposed a 300 MW gas fired peaking power station with plans for green hydrogen which will receive AUD 83m combined from the New South Wales and federal governments (Murphy, 2021). The plan for green hydrogen has been criticised for propping up fossil fuels as it supports the gas project without reducing emissions due to the low levels of green hydrogen blending (Joshi, 2021). The Australia Energy Market Operator reports highlights the uncertainty of the gas sector within the next 20 years, as scenarios show possible decline from economic activity, closure risks and hydrogen substitution (AEMO, 2021a).

The New South Wales gas plans contradict analysis by the Liddell Task Force that assessed the impacts of Liddell’s closure and ignores latest plans for investments in large-scale batteries including by the owner of Liddell (AGL) (DISER, 2020). Gas plans also contradict advice from government agencies and industry groups, as well as research organisations, with the Australian Energy Market Operator publishing scenarios for integrated grid planning that show no expansion of gas-fired power generation is necessary (AEMO, 2020). The threat of government subsidised competition and backtracking on statements creates high uncertainty for investors.

On the other hand, the Climate Council has called for a clean jobs plan, demonstrating how 76,000 new jobs could rebuild the economy whilst transitioning to a low-carbon economy (Climate Council, 2020). The plan is based on economic modelling analysing each state and territory, with shovel ready opportunities targeted at the hardest hit regions and occupations with job losses. Examples of policies and employment opportunities covered in the plan include 15,000 jobs in utility scale renewables, 12,000 in targeted ecosystem restoration, 12,000 for accelerated public and active transport infrastructure, 10,000 jobs for organic and food waste collection and processing, in addition to jobs in public building retrofitting, residential retrofitting and urban gardens.

In a 2020 study, the Climate Action Tracker found that accelerating towards a zero carbon power sector would create 46,000 additional jobs from 2021 to 2030, and with local manufacturing of wind turbines, solar panels and batteries, and that this could be scaled up to 76,000 jobs.

Technology-neutral over climate focus

Australia’s long-term climate strategy is at risk of deprioritising effective low-emissions technology. The government released a “Technology Investment Roadmap Discussion Paper” in May 2020 for public consultation (Australian Government, 2020e). The government also released the first “Low Emissions Technology Statement” specifying the government’s technology investment priorities (Australian Government, 2020c). The discussion paper indicates a “technology neutral” approach to investment, with support for gas and CCS (as well as renewables), without ruling out coal and nuclear power.

In 2019, the government called upon fossil fuel industry stakeholders to conduct a non-transparent review of climate policies, producing the ‘Final Report of the Expert Panel examining additional sources of low-cost abatement’ (named ‘the King Review’) (Mazengarb, 2019; Morton & Murphy, 2019). The government has followed many of the recommendations, including amending the Emissions Reduction Fund to allow for carbon capture and storage technology and expanding Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) and Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC) remit to take a “technology neutral” approach (Australian Government, 2020a, 2020b).

The Morrison government has tried to change the remit of ARENA to include CCS and blue hydrogen production, but this was rejected by the Senate (Coorey, 2021). The CEFC Act currently prohibits the CEFC from financing CCS projects (Clean Energy Finance Corporation Act, 2012). The government has already spent AUD 233m on the National Low Emissions Coal Initiative and budgeted AUD 1bn on the CCS Flagships program expiring in 2020 (Australian National Audit Office, 2017). There is no CCS programme in operation in the electricity sector, and the only operating CCS project, the Gorgon gas project in Western Australia, has encountered numerous problems, resulting in capturing less carbon than contractually agreed, and commencing years later than planned (Morton, 2019).

Climate Solutions Package and the Emissions Reduction Fund

The 2019 Climate Solutions Package has been criticised in the media as a rebranding of old policies (Australian Government, 2019; Murphy, 2019). The package includes the rebranded Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF) (now called the Climate Solutions Fund), unspecified energy efficiency measures, government investment into a “Battery of a Nation” project (new power links between Tasmania and the mainland), and the announcement of the electric vehicle strategy.

The government claims these policies, along with energy performance standards (for air-conditioning and refrigeration), previous policies and projects such as Snowy 2.0, and unspecified “technology improvements”, will allow Australia to meet the 2030 target (Australian Government, 2019). The package does not detail how it will meet the Paris commitments. The package suggests 100 MtCO2e of abatement is derived from unspecified “technology improvements and other sources of abatement” and another 10 MtCO2e from the electric vehicle strategy.

Australia’s Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF) - which is now part of the Climate Solutions Fund - is a reverse auction mechanism that is supposed to reduce emissions in a cost-effective manner. The Clean Energy Regulator, which serves as the economic regulator of the ERF, has indicated the fund avoided a mere 4 MtCO2e of emissions over the four auction rounds in 2017 and 2018, despite 123 contracts worth AUD 372m (ABC News, 2019c).

By the twelfth auction in April 2021, 43 projects had been completed and 461 contracts were in hand (Clean Energy Regulator, 2021a). So far, the ERF has delivered a nominal total of 66 MtCO2e in abatement, and has 138.9 MtCO2e of abatement contracted to be delivered. These figures exclude terminated or lapsed contracts worth 17.3 MtCO2e in emission abatements as businesses did not deliver the agreed abatements.

In 2019, the ERF’s rebranding as the “Climate Solutions Fund” included a top up of AUD 2 billion. However, the government effectively cut the funds from AUD 200m to AUD 133m per year by spreading the AUD 2bn over 15 years rather than ten. The government wants to continue relying on an instrument that has been the subject of fiscal concern due to its cost to the taxpayer, and against the advice of the government-appointed advisory body the Climate Change Authority to introduce new policies aiming at decarbonisation and structural change (Climate Change Authority, 2017).

Business interest in the scheme has declined. The eleventh auction saw 35 contracts awarded (6 fixed and 29 optional) whereas the twelfth auction had 10 contracts (1 fixed and 9 optional) (Clean Energy Regulator, 2021a).

The fund has also been plagued by a mismatch of its abatement profile, concentrated in the land and waste sector, with Australia’s emissions driven by industrial, transport, and power sectors. There is a high risk of reversal of stored carbon in land sector projects being emitted again (Climate Change Authority, 2017), particularly in light of the widespread bushfires of November 2019 to January 2020. There are also serious doubts about the additionality of many of the ERF projects (Baxter, 2017).

Australia’s emissions per capita rank seventh highest in the world (Australia Institute, 2019).

States and territories

All states (and in addition, the Northern Territory and ACT) now have zero emissions targets for 2050 with strategies or action plans for implementation (Climate Council, 2018a; Government of Western Australia, 2019; Northern Territory Government, 2019). The ACT and Victorian Government have legislated their targets. The ACT set an ambitious target earlier than 2050, to achieve zero net emissions by 30 June 2045 (ACT, 2019).

The state of Victoria recently ramped up its climate commitments in its Climate Change Strategy with a target to cut emissions 45 to 50% from 2005 levels by 2030 (Victoria State Government, 2021). While the federal government has failed to increase its far less ambitious target of 26 to 28% from 2005 levels by 2030.

Public Opinion

A poll from June 2020, found that 70% of Australians expect the government to protect the environment as part of the economic recovery efforts (IPSOS, 2020). Another poll found 72% of Australians view the bushfires of November 2019 to January 2020 as a wakeup call on the impacts of climate change, with 73% agreeing that the Prime Minister should lead climate action (Australian Institute, 2020).

The Australian Climate Roundtable, an alliance of leaders from business, farming, investment, union, social welfare and environmental sectors issued a statement calling on the government to adopt a net-zero emissions by 2050 target. The statement also recommends policies to unlock private sector investment in resilience, and integrating the COVID-19 recovery with mitigation efforts (Australian Climate Roundtable, 2020).

A report by the Climate Council documents the compounding costs of Australia’s vulnerability to climate change (Climate Council, 2021). For instance, climate and weather disasters have cost Australia AUD 35 billion from 2010 to 2019 and will be largely uninsurable in flood and bushfire prone communities (ABC News, 2020; Climate Council, 2021).

Energy supply

COVID-19 did not have a substantial impact on electricity sector emissions. Electricity sector emissions have decreased 4% over the past year as renewable energy displaces coal fired power generation (September 2019 to September 2020) (DISER, 2021a). However, the ramp up of renewable energy has not been sustained. During July to September 2020, renewable generation declined 7.3% and coal generation increased 1.5% (DISER, 2021a).

The electricity sector represents 32% of total emissions excluding LULUUCF (Australian Government, 2020f). Government projections indicate the electricity sector will decrease emissions 35% in the next decade (Australian Government, 2020f). However, there is no explicit emissions reduction policy for the electricity sector, and instead an explicit push to support gas and coal-fired power generation.

Coal

Coal is the major beneficiary of government spending with AUD 631 million budgeted in 2020-21 across national and state governments, with Queensland spending a significant potion (over AUD 431 million) (Campbell et al., 2021). The government has encouraged utilities to extend the coal-fired power generation lifespan beyond scheduled shutdown dates (Taylor, 2019). It also continues to support fossil fuel electricity generation, offering incentives through a power subsidy, considering support for a new coal fired power plant (“Underwriting New Generation Investment Scheme”) (Coorey, 2019; DEE, 2019c).

The government is financing AUS 4 million for a study into a new coal fired power plant in Queensland (Thornhill, 2020). This stands in stark contrast with the need to phase out coal by 2030 (Climate Analytics, 2019a). Scenarios by the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) show a cost-effective pathway towards high shares of renewable energy can be achieved with policy and planning (AEMO, 2020).

The federal government refuses to discuss any emissions reduction policy for the electricity sector, claiming it wants to focus on reducing prices and supporting investment in coal and gas to ensure reliability despite all evidence pointing to the fact that this would lead to higher costs than investing in more renewable energy (Toscano & Harris, 2019). The Energy Security Board has recommended coal fired generators could be paid to stay operational and prevent closure (Mazengarb, 2021a).

Despite government support for coal, there is little appetite for new coal generation — neither from utilities and industry, nor from the general public. In the past year, renewable energy has displaced some black coal, particularly in Mount Piper power station NSW (Saddler, 2020). Nine coal-fired power stations have been retired in the last five years, including Hazelwood, a 1.6 GW lignite coal-fired plant in the state of Victoria. This illustrates the economic challenges coal plants face in Australia against the continuously decreasing costs of renewables and storage. There is increasing concern about the lack of reliability of aging coal-fired power plants, with renewable energy and increasing use of modern storage technologies proving to contribute more and more to reliability (Gas Coal Watch, 2018; IEEFA, 2018; RenewEconomy, 2018).

LNG and oil

Within the energy sector, direct combustion emissions are increasing and projected to increase further with the ramping up of LNG export facilities, mainly in Western Australia and Queensland. Emissions from stationary energy (excluding electricity) have increased 1.7% over the past year due to LNG exports (Sept 2019 to Sept 2020) (DISER, 2021a). This increase in gas production is also leading to a large increase in fugitive emissions.

While oil production has declined in Australia since 2010, natural gas production has vastly increased since 2011-12. Substantial growth of 117% occurred between 2013-14 to 2018-2019 (Australian Government, 2020f). Production will be ramped up to 88 Mt by 2030 (Australian Government, 2020f).

Such plans for LNG production raises questions over the increasing uncertainty and risk of stranded assets, and decreasing exports and revenues with signs of increasing oversupply due to the economic down related to the COVID-19 pandemic (Macdonald-Smith, 2020a, 2020b). Gas customers are likely facing gas bill price hikes as gas pipeline assets lifespans may be cut short as renewables become cheaper (Parkinson, 2021). There are delayed investment decisions relating to the massive Burrup Hub expansion planned off the Western Australian coast, which would alone contribute an additional 16 MtCO2e by 2030 if it were to go ahead (Climate Analytics, 2020; Morton, 2020a). Coal production will also be ramped up from 606 Mt in 2020 to 646 Mt in 2030 (Australian Government, 2020f).

The industry benefits from tax rebates, the most prominent being the fuel tax credit scheme (Australian Taxation Office, 2017). Another subsidy is the statutory effective life caps. This subsidy can be applied to oil and gas assets to accelerate the depreciation, and the taxable amount on the asset (ODI, 2015). These subsidies support fossil fuel industry and their exports, despite the need for global phase out.

What is not measured in national level greenhouse gas accounts is the emissions from LNG and coal at the export destination. Under government projections for coal and gas production, Australia’s extraction based emission from fossil fuel production would nearly double (95% increase) by 2030 compared to 2005 levels (UNEP, 2019).

Renewables

Renewable energy generation has increased in recent years from 9% of total electricity generation in 2005 to 23% in 2020 (Australian Government, 2020f). Government projections indicate 55% of electricity will be generated with renewable energy by 2030 (Australian Government, 2020f). The projections show a year on year growth in renewable generation and consequently there is a projected 35% decline in electricity sector emissions from 2020 to 2030 (Australian Government, 2020f).

The largest electricity grid in Australia is the National Energy Market (NEM) covering a large share of the eastern states. Government projections indicate the NEM will be 55% renewable by 2030 (Australian Government, 2020f). Whereas Australian Energy Market Operator’s (AEMO) Chief Systems Design Officer indicates the NEM is currently ahead of a 90% renewables scenario for 2040, based on the pipeline of registered and commissioned renewable energy projects (AEMO, 2021b).

A number of studies show the technical and economic feasibility of a transition to 100% renewable energy by the 2030s through simple and affordable policies, such as incentives for dispatchable renewables and storage, funding for transmission links, and incentives or legislation for retiring high polluting coal power (Blakers et al., 2017; Diesendorf, 2018; Gulagi et al., 2017; Howard et al., 2018; Riesz et al., 2016; Teske et al., 2016).

Renewable energy is the lowest cost option for power in Australia however investments will decline due to a lack of targets and planning at the federal level. Wind and solar are the lowest cost option for electricity generation in Australia compared to any new build technology, including an additional six hours of storage (BloombergNEF, 2019; CSIRO, 2018). The renewable energy sector has experienced growth, but investments in renewables are predicted to decline and curtailment and delays to grid connections are becoming an increasing problem (De Atholia et al., 2020; RenewEconomy, 2020).

Reasons for the decline in investment include policy uncertainty, regulatory risks, grid connector issues and lack of investment in the network (Clean Energy Council, 2020a, 2020b; McConnell, 2019). Small-scale renewable energy is experiencing strong growth due to the uptake of rooftop solar by private households and small businesses. In 2020, 3 GW of new small scale solar systems were installed, a rise from 2.7 GW in 2019 and despite the impacts of the global COVID-19 pandemic (Clean Energy Council, 2021). It marks the fourth year of record breaking in capacity additions (Clean Energy Council, 2021).

Ironically, the proposed government investment to fast track the “Battery of the Nation” project (new power links totalling 1.2 GW of capacity between the island state of Tasmania with considerable hydro and wind resources and the mainland of Australia) has been assessed to only make financial sense with an acceleration of coal retirement and an acceleration of renewable energy investments, according to a feasibility study (TasNetworks, 2019).

The outlook is clouded, as many analysts believe further incentives and/or structural changes in the electricity market, including the establishment of adequate grid into connectors is essential for the recent growth to continue at the same rate. For example, a recent study finds that Australia could build an affordable and secure electricity network with 100 percent renewable energy, using existing technologies, but with the need for stronger interconnections between regions (Blakers et al., 2017).

A report by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and Energy Networks Australia (ENA) finds that a decarbonised energy grid by 2050, with half of generation produced and stored locally, would save billions in upfront capital costs and consumer bills, and deliver a secure electricity system (Australia Energy Networks & CSIRO, 2016). The Energy Transition Hub’s new scenario analysis shows the potential for ‘200% renewable energy’ to support domestic demands and RE exports (Burdon et al., 2019) presenting recommendations that have been ignored by government.

Nuclear

Nuclear power is prohibited by law in Australia under the Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Act 1998 (the ARPANS Act), and the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (the EPBC Act) (Cronshaw, 2020). The government held an inquiry into the prerequisites for nuclear energy in Australia, which was open to public written submissions in September 2019 (Parliament of Australia, 2019). In response to the inquiry, the Environment and Energy Committee recommended the government consider nuclear energy in the future energy mix (Standing Committee on the Environment and Energy, 2019).

Energy Efficiency

The National Energy Productivity Plan 2015–2030 aims to improve energy productivity by 40% by 2030 through “encouraging more productive consumer choices and promoting more productive energy services” (Australian Government, 2015). However, research suggests that much more ambitious improvements are possible, with a doubling of energy productivity possible by 2030 with net benefits for GDP (Energetics, 2015). Five years after its publication, its impact has yet to materialise.

The government introduced the Energy Efficient Communities Program in 2019 committing AUD 50 million in grants for businesses and community organisations to improve energy efficiency and reduce electricity bills (DEE, 2019b). By 2020, this program’s budget was reduced to AUD 40 million (Department of Industry Science Energy and Resources, 2020a).

Along with setting and encouraging efficiency standards, governments can support energy efficiency improvements across sectors by setting ambitious goals, providing funding and financial incentives. The American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE) has scored these elements of national commitment and leadership—Australia ranks 18 of 25 (Castro-Alvarez et al., 2018). The IEA came to the same conclusion: out of 28 countries, Australia is the only country not making any real progress (OECD/International Energy Agency, 2017).

States and territories

States and territories are stepping up and committing to their own targets. Six out of eight states and territories in Australia have committed to a renewable energy target in or beyond 2025 (Climate Council, 2019). Some states have set ambitious targets for 100% of renewable energy:

- ACT has committed to 100% renewables by 2020

- Tasmania aims to be 100% self-sufficient in renewable energy by 2022 (Climate Council, 2019). It has set a new ambitious target for 200% renewable energy by 2040 (Gutwein, 2020).

- South Australia is a global leader in terms of the share of variable renewable energy (wind and solar PV) at 51% in 2018 (Department of the Environment and Energy, 2019a). It met its 50% renewable energy production by 2025 target in 2018 (Department of the Environment and Energy, 2019a). It also leads in storage technology with the world’s biggest lithium-ion batteries and one of the world’s biggest solar thermal plants. The state has plans for the world’s biggest “virtual power plant”, i.e. the installation of solar panels and batteries on more than 50,000 homes, and for investments into green hydrogen from renewable energy for storage and export (Morton, 2018)

- Queensland, Victoria, and the Northern Territories have committed to 50% renewables by 2030 (Department of Energy and Water Supply., n.d.; Langworthy et al., 2017; Victoria State Government, 2019)

- Western Australia and New South Wales do not have a renewable energy target.

Around 35% of dwellings in South Australia, 36% in Queensland and 29% of Western Australia had solar PV by 2019, a trend that is showing no sign of slowing down (Climate Council, 2019). This is not a boom driven by a pending reduction in subsidies, rather by high electricity prices, highly affordable solar power systems, and people’s desire to act on climate change.

Industry

Australia’s emissions from industry1 (stationary energy excluding electricity, fugitives,2 and industrial processes) account for 35% of total emissions (excluding LULUCF), making it the largest emitting sector (Australian Government, 2020f).

The only industry sector policy that is projected to create a fall in emissions is the hydrochlorofluorocarbon (HFC) phase down legislated in 2017 (Australian Government, 2020f). The phase-down will reduce the total quantity of permitted HFC imports every two years until an 85% reduction from 2011–2013 levels is achieved by 2036 (Government, 2017).

There is no strategy or plan by the government or industry to decarbonise the industry sector and transition away from fossil fuels, despite the many studies demonstrating Australia’s industry sector can decarbonise its industry sector and transition away from fossil fuel (BZE, 2019; Climate Analytics, 2018; ClimateWorks Australia, 2014, 2020).

In November 2019 the government released the National Hydrogen Strategy, developed by the Council of Australian Governments’ (COAG) Hydrogen Working Group (COAG Energy Council, 2019). Renewable energy-based hydrogen is an opportunity for the integration of large shares of renewable energy and decarbonisation of end-use sectors in particular in heavy freight transport and industry where direct electrification is not feasible.

However, the National Hydrogen Strategy refers to a “technology-neutral” approach and defines “clean hydrogen” as “hydrogen produced using renewable energy or using fossil fuels with substantial carbon capture”. There is a risk that it will be used to prop up the fossil fuel industry in Australia.

In comparison, there is a Hydrogen Energy Supply Chain coal to hydrogen project with a budget of 500 million AUD from various Australian and Japanese sources, of which the Australian government and the Victorian government are contributing 50 million AUD each (Seccombe, 2019). The pilot project will not implement carbon capture and storage, but may offset emissions, and carbon capture and storage will only be installed if the full project goes ahead as part of the CarbonNet Project for sequestration, on which the federal and Victorian governments have so invested some AUD 150 million (due in 2030) (Seccombe, 2019).

Both South Australia and Western Australia have renewable hydrogen strategies (Government of South Australia, 2017; WA Dept. of Primary Industries and Regional Development, 2019) and the Queensland government has released a Hydrogen strategy focusing on green hydrogen and export opportunities (Queensland Government, 2019). Experts say that with the right conditions, Australian hydrogen exports could be worth AUD 1.7 billion a year and could generate 2,800 jobs by 2030 (ACIL Allen Consulting, 2018).

Australia’s Safeguard Mechanism began operations in July 2016, with a goal of limiting significant emissions increases from large industrial sources to a baseline emissions level. This mechanism applies to around 140 businesses that have facilities with direct emissions of more than 100 ktCO2e.

High-emitting industrial facilities covered by the safeguard mechanism will drive national emissions growth through to 2030. In March 2019, baselines were increased, allowing emissions to increase (Department of the Environment and Energy, 2019b). The mechanism has been criticised for serving no purpose (Morton, 2020c). Baseline changes have led to projected increase of emissions from these facilities by 12% in the two years of operation, cancelling out publicly funded emissions reductions under the Emissions Reduction Fund (Morton, 2020c).

The government intends to offer an incentive scheme allowing large emitters to earn revenue for emitting less than under the safeguard mechanism baselines (Australian Government, 2020a, 2020b). Without reducing the baselines, large emitters will be paid while the policy remains ineffective in emissions reductions (Morton, 2020b). The safeguard mechanism has not been designed to reduce emissions, but rather to limit them. But approving flexible safeguard mechanism baselines has achieved the opposite, letting companies increase their baseline emissions. Declining baselines would be much more effective policy update (Climate Change Authority, 2020).

A recent government announcement indicates carbon capture and storage projects will qualify under the emissions reduction fund (Australian Government, 2020a, 2020b). This move has been highly criticised, as it adds to the mounting taxpayers dollars that have been spent on CCS—with few signs of commercial or environmental viability (Mazengard, 2020).

The Clean Energy Regulator is developing a carbon exchange to streamline trading of Australian carbon credit units (ACCUs). ACCUs are issued as part of the Emissions Reduction fund and the carbon market may support further engagement with the voluntary emissions reduction for businesses (Clean Energy Regulator, 2021b).

The federal and state government have both approved the start of what could prove to be the biggest coal mine in the world, the Adani mine in Queensland (ABC News, 2019a, 2019b). The Adani project is currently on hold as the Federal Court upheld a challenge to the approval of the project relating to environmental impacts (EDO, 2021).

1 | The Industry Sector includes direct combustion emissions from manufacturing, energy, and mining (but not from buildings, military, nor from agriculture and fisheries), and fugitive emissions (coal, oil, and gas), as well as industrial processes and product use emissions.

2 | Fugitive emissions in this section refers to emissions from the extraction, processing and delivery of fossil fuels.

Transport

In 2020, transport emissions represented 18% of total emissions (excluding LULUCF) and are projected to increase 6% by 2030 (Australian Government, 2020f). Cars represented over 40% of transport emissions in 2020 and are still projected to represent over 40% in 2030. Transport emissions should decline, particularly with the right policies in place related to increased energy efficiency and the rise of electric vehicles, but there a few effective policies.

Lockdown measures resulted in a temporary decline in transport sector emissions. Restrictions caused a 10.2% decline in emissions in the past year according to the latest government quarterly emissions report (DISER, 2021a). Australia experienced a 10.7% decline in petrol consumption and a 0.2% decline in diesel consumption (Sept 2019 to Sept 2020) (DISER, 2021a). However, emissions from the September 2020 quarter increased nearly 12% as transport activity resumed (DISER, 2021a).

The government released a Future Fuels Strategy for consultation (DISER, 2021c). The strategy rules out government subsidies for electric vehicles (EVs) and setting a date for phasing out fossil fuel vehicle sales. The strategy focuses on the benefits of hybrids over EVs, as it notes EVs only have lower emissions in South Australia and Tasmania compared to a hybrid vehicle. Emissions will be high for EVs given the fossil fuel intensive electricity grids in most states and territories backed by a government supporting a “gas-fired recovery”.

So far the government has relied on financing for businesses to upgrade their fleets, with just over 1000 lower-emissions vehicles financed through industry partnerships (Australian Government, 2017). The government provides exemptions from some vehicle taxes for highly efficient vehicles. The emissions reduction fund has not contracted emissions abatements in the transport sector since the second auction in November 2015, (there have been 10 further auctions since) (Clean Energy Regulator, 2021a).

Yet, the government is supporting fossil fuels with up to AUD 200m in grants for the construction of diesel storage in a program running for three years (DISER, 2021b).

The government established a Ministerial Forum to coordinate federal and state government approaches to addressing emissions from motor vehicles, including consideration of a fuel efficiency standard for light vehicles (Australian Government, 2017) but still has no standards at all, and has not taken any decision on introducing such standards, while nearly 80% of new light duty vehicles sold globally are subject to some kind of emissions or fuel economy standard (Climate Analytics, 2019b). The Climate Change Authority (2020) recommended implementing a GHG standard for light duty vehicles, and a cost-benefit analysis for an emissions standard for heavy duty vehicles.

Adopting strict standards could prevent up to the equivalent of 65 MtCO2 by 2030, which is significantly more greenhouse gas pollution than what New South Wales’ entire coal fleet produces in a year (Climate Council, 2018b). They would also significantly reduce car owners’ fuel bills, saving an estimated AUD 8,500 over a vehicle’s lifetime.

Compared to other countries, the uptake of electric vehicles (EVs) is very slow in Australia. The market share of electric vehicles in Australia is 1% of new vehicle sales, in comparison to over 6% in other developed countries (see graph below). The sales of electric vehicles tripled in 2019 despite the lack of government support (Electric Vehicle Council, 2020). Australian Government projections indicate EVs (including plug in hybrids) will represent only 26% of new light duty vehicles by 2030 (DISER, 2021a).

EV market share

National and state governments have offered some support for electric vehicle recharging infrastructure by installing public chargers (Climate Change Authority, 2019). Most states (ACT, NSW, VIC, QLD, SA) offer different degrees of registration discounts for electric vehicles.

The State of South Australia plans to lead Australia in EV uptake with AUD 18.3m budgeted for the Electric Vehicle Action Plan with an aim for all new passenger vehicles sold to be fully electric by 2035 (Government of South Australia, 2020). The ACT government and Transport Canberra have trialled electric and hybrid buses and ACT has now released an Action Plan for zero-emissions vehicles. ACT—with a target to achieve net-zero GHG emissions by 2045—has introduced financial incentives for zero-emissions vehicles (exemptions from stamp duties, reduced registration fees), adopted zero-emissions vehicles in government fleet, and is investigating opportunities for production of hydrogen fuel and deployment of fuel cell electric vehicles in the government fleet (ACT Government, 2018).

Buildings

The buildings sector accounts for 57% of Australia’s electricity usage and energy efficiency in buildings and appliance is essential to decarbonise (Climate Action Tracker, 2020). There is widespread undercompliance with the present minimal energy efficiency standards (Climate Action Tracker, 2020). The National Construction Code is not deemed effective in providing adequate energy efficiency in buildings, and is not due to be updated until 2022 (Climate Action Tracker, 2020). Slow policy responses for long-lived assets mean that renovation rates will need to be scaled up, but there is no policy at all that focuses on increasing building renovation rates (Climate Action Tracker, 2020). Australian efficiency standards are behind other countries with similar climates (Climate Action Tracker, 2020). Failure to ensure adequate levels of energy efficiency in buildings places further pressure on the electricity grid to decarbonise.

Agriculture

Agriculture accounted for 13% of Australia’s total emissions in 2020 (excluding LULUCF), and is projected to increase emissions by 12% by 2030 (Australian Government, 2020f). Emissions from agriculture have fallen by 14% due to the impacts of drought (DISER, 2021a). Livestock populations and crop production have not fully recovered (DISER, 2021a).

Emissions in the agriculture sector are derived from enteric fermentation (digestive processes of some animals), liming and urea application, manure management, rice cultivation, agricultural soils and field burning (DEE, 2019a). Operating equipment, fuel and electricity in this sector are covered in the other relevant sectors such as electricity.

The Carbon Farming Futures programme ran from 2012 to 2017, and invested 139 million AUD in 200 projects and 530 farm trials (Department of Agriculture and Water Resources, 2017). It promoted research and best practice techniques to reduce emissions. The only policy to disseminate regional best practise and ramp up research came to an end and has not been replaced.

The Climate Change Authority has also noted the need for a ramp up of research in this sector, and recommends the allocation of additional funds for low emissions agricultural research and carbon farming, in addition to investment and incentives to support “climate-smart” and low emissions agriculture and environmental services (Climate Change Authority, 2020).

While the forest sector is currently a net sink, and regrowth of Australia’s previously harvested forests outweigh the forests that are currently harvested, the rate of forest clearing is still high (Australian Government, 2020f).

The Australian government has made a preliminary estimate of net emissions for the 2020 fire season of around 830 MtCO2e (based on the fires up to 11 February 2020) (Australian Government, 2020d). Emissions from wildfires such as the devastating and unprecedented bushfires in 2019/2020 that burnt an estimated 7.4 million hectares of forest (mostly in national parks and conservation areas) are not accounted for in the inventory, as they are treated as a “natural disturbance” beyond control, and it is assumed that the equivalent amount will be sequestered during forest recovery (Australian Government, 2020d). Anthropogenic fires are included in the inventory, for example from prescribed burning (Australian Government, 2020f).

Australia is the only developed country that is classified as a deforestation hotspot in the world, with estimates that three to six million hectares of forest could be lost by 2030 in Eastern Australia (Slezak, 2018; WWF, 2018).

Government LULUCF emissions data is regularly recalculated for historical and projected emissions. The recalculations highlight how uncertain this sector is, and data changes have significant repercussions on Australia’s progress on meeting emissions targets. The CAT takes into account the uncertainty of these projections (see the assumptions section for details).

Waste

The waste sector emissions represent 2% of total emissions excluding LULUCF (Australian Government, 2020f). Emissions from the waste sector are the result of mainly methane related to landfill, wastewater treatment, waste incineration and treatment of solid waste. Emissions from waste have decreased in the last year by 2.7% resulting from gas capture at landfill sites (DISER, 2021a).

The national waste policy does not focus on reducing emissions from this sector (Climate Action Tracker, 2020). The Emissions Recuction Fund (ERF) portfolio has at least 106 landfill and waste projects, and the safeguard mechanism limits emissions at large landfills, although this policy does not cover legacy emissions before July 2016 (Climate Action Tracker, 2020). There are also concerns over the success of the ERF, as it covers projects that would have abated emissions without the scheme (Climate Action Tracker, 2020).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter