Country summary

Overview

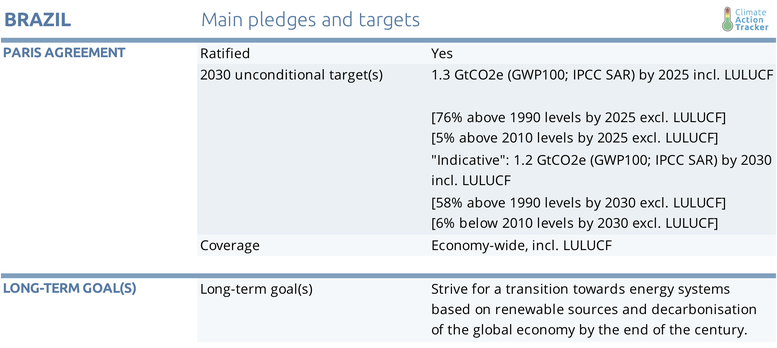

NDC update: In December 2020, Brazil submitted an updated NDC. Our analysis of its new target is here.

Brazil is facing an ongoing challenge to get the COVID-19 pandemic under control. Brazil’s initial response to the pandemic has further weakened environmental regulations. It appears likely, based on past performance, that the Bolsonaro administration will continue in the wrong direction, disregard the urgent need for climate action in Brazil, and will not take up the opportunity to pursue a green economic recovery. The CAT rates Brazil as “Insufficient”.

We expect that Brazil’s GHG emissions in 2020, excluding LULUCF, will drop by about 4% from 2019 levels. Social isolation measures have led to a reduction in fossil fuel combustion for transport and electricity generation during the second quarter of 2020, and a downturn in activity in the industrial sector. However, emissions from agriculture are set to maintain an upward trend, as fewer livestock are being sent to slaughter.

Brazil is still under the throes of COVID-19; hence its economic recovery lies predominantly in the future. Early signs indicate that the Bolsonaro administration has rather sought to use the pandemic to accelerate - and distract attention from - the rollback of environmental regulations. For example, legislators have recently attempted to use the fast-track legislation process put in place for COVID-19 measures to approve highly controversial ownership rights for illegally deforested land. Meanwhile, environmental enforcement agents have been asked to self-isolate at home.

There are significant gaps in Brazilian policymaking for halting emissions growth. The continued roll-back of forest protection policies is enabling ever higher deforestation rates, pushing emissions from Brazil’s largest source – deforestation – upwards after more than a decade of decline. In 2019, over one million hectares of land was deforested in the Legal Amazon – a 34% increase on 2018, and 120% larger than the historic low reached in 2012; an even greater area is expected to be deforested in 2020. The month of July 2020 already saw more forest fires than July 2019, a worrying sign of what might be to come. This trend takes Brazil in the opposite direction of its Paris Agreement commitments, which include a target of zero illegal deforestation in the Brazilian Amazonia by 2030.

The agriculture sector remains the second largest contributor to Brazil’s GHG emissions after deforestation, and itself is a key driver of deforestation, yet we find no new policy instruments or regulations to advance the implementation of emissions mitigation in this critical sector.

For the energy sector, market trends for renewable power generation are positive, with a steady increase in wind and solar capacity. However, the postponement of electricity generation auctions scheduled in 2020, coupled with the fall in energy demand during the COVID-19 crisis, may harm the competitiveness of solar and wind companies, which are often much smaller than their fossil fuel competitors. Policy developments during Brazil’s COVID-19 recovery may ultimately limit the options for long-term deep decarbonisation of the economy by locking Brazil into a carbon-intensive energy infrastructure. A clear cause for concern is Brazil’s energy infrastructure planning, which unnecessarily continues to incorporate fossil fuels, including coal and gas. In addition, Brazil has provided unconditional financial support to the airline industry as it recovers from COVID-19.

The CAT’s projections for Brazil’s emissions excluding LULUCF in 2030 are 4-5% lower than our previous assessment in December 2019. This is due to the impact that COVID-19 and the contraction of Brazil’s economy are expected to have on emissions from energy (including transport) and industrial processes. Such a reduction would make it possible for Brazil to meet its 2025 NDC target (bringing emissions to 1-2% above the target level, when LULUCF is excluded). But without a sustained drop in emissions beyond the early 2020s, Brazil would still be off track for its 2030 NDC target. If we also consider the upwards trend in deforestation emissions, Brazil is most certainly not on track to deliver on its NDC.

The CAT rates the existing Brazil target under the Paris Agreement as “Insufficient”, as it is not stringent enough to limit warming to 2°C, let alone 1.5˚C.

According to our most recent assessment, Brazil will need to implement additional policies to meet its NDC targets. Taking the impacts of COVID-19 into account, our analysis finds that Brazil’s current policies will take emissions levels (excluding LULUCF) to 1,001 – 1,010 MtCO2e in 2025 and 1,029 – 1,039 MtCO2e by 2030 (respectively, 18 – 19% and 22 – 23% above 2005 levels and 78 – 79% and 83 - 85% above 1990 levels).

Under this scenario, emissions in the energy and industry sectors fall during the COVID-19 economic recession before resuming their increasing trend, reaching 2018 levels by 2026. Meanwhile, emissions in the agriculture and LULUCF sectors are expected to continue to increase until 2030 at least. Major gaps remain in the current administration’s policymaking for halting emissions growth, and its response to the COVID-19 pandemic so far has not been in line with a green recovery.

The main policy instruments included in our current policy projections pathway are the energy efficiency national plans and the incentives for the uptake of renewables in the energy sector, including capacity auctions in the power sector, and the ethanol and biodiesel mandates in the transport sector, as well as the national biofuels policy RenovaBio. Brazil has enacted other sectoral plans to reduce emissions in other sectors of the economy, but most of those policies and instruments are still not part of national development planning or regulation, hence we have not included them in our current policy projections emissions pathway.

Deforestation rates have increased rapidly in recent years, and 2020 is set to be no exception. The rise in illegal deforestation is linked with a systematic dismantling of Brazil’s institutional and legal frameworks for forest protection, and takes Brazil in the opposite direction of its deforestation commitments. Brazil has a 2020 commitment to reduce deforestation by 80% from 1996-2005 levels, and its Paris Agreement commitments include a target of zero illegal deforestation in the Amazonia by 2030. Both of these are set to be missed.

Agriculture is the second largest source of emissions in Brazil, and has been a key driver of deforestation. Despite the clear potential for low-cost mitigation opportunities that could raise agricultural productivity while lowering emissions and reducing deforestation, the government has not brought forward any new low carbon agricultural policies or regulations.

On energy, under current policy projections, the indicative NDC target of a 45% share of renewables in the total energy mix by 2030 will be overachieved, with renewable energy expected to represent 47% of the energy mix in 2027 and 48% in 2029 according to the most recent energy plan. This high renewable share in Brazil is enabled by the large shares of hydro in power generation and bioenergy in transport. However, unless additional policies are put in place, emissions in the energy sector will resume a rising trend as Brazil’s economy recovers from the impacts of COVID-19, locking Brazil into a more carbon intensive energy system and leaving much of Brazil’s considerable potential for renewable power generation untapped.

On transport, while biofuels have contributed significantly to improve the emissions intensity of the road transport sector in Brazil, full decarbonisation of the transport sector will require a fast uptake of electric vehicles (EVs). In terms of EVs, Brazil is a laggard, with a very small penetration rate and without a clear strategy to substantially increase the adoption of this technology.

To peak emissions and rapidly decrease levels afterward as required by the Paris Agreement, Brazil will need to reverse the current trend of weakening climate policy, by sustaining and strengthening policy implementation in the forestry sector and accelerating mitigation action in other sectors— including a reversal of present plans to expand fossil fuel energy sources.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter