Policies & action

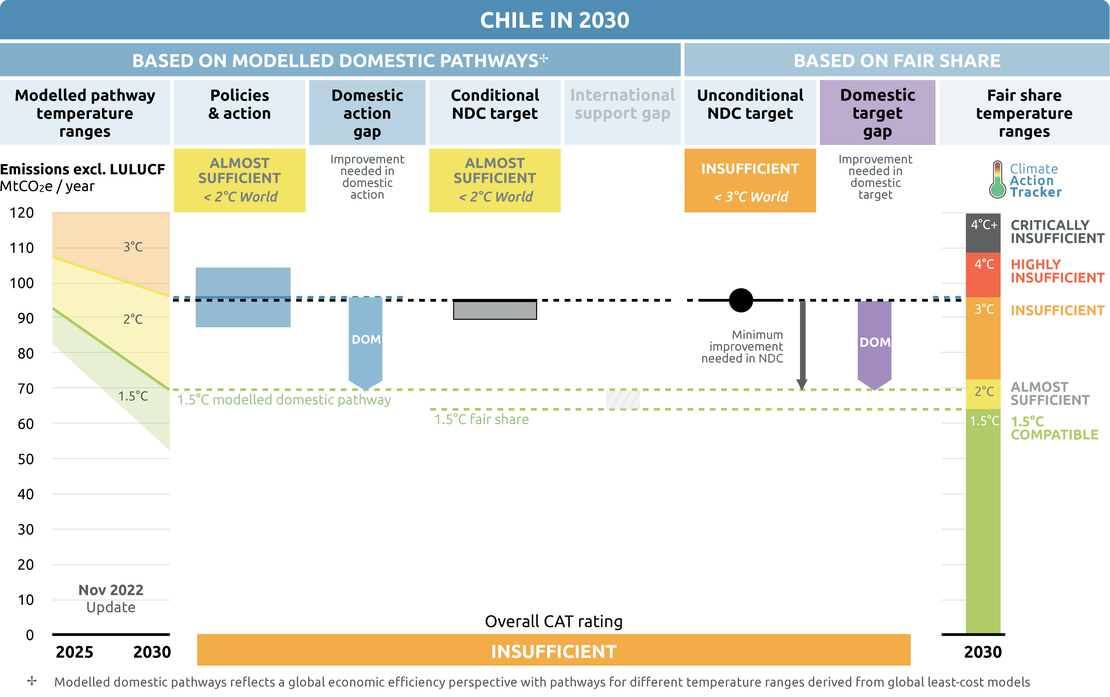

The “Almost sufficient” rating indicates that Chile’s climate policies and action in 2030 are not yet consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C but could be, with moderate improvements. If all countries were to follow Chiles´s approach, warming could be held at—but not well below—2°C. If we were to rate Chile’s planned policies, the lower end would be “1.5° compatible”.

According to our assessment, emissions under Chile’s currently implemented policies would reach levels between 87 and 104 MtCO2e excl. LULUCF by 2030 (3% to 18% below 2021 levels). This range is sufficient to reach the 2030 NDC target (95 MtCO2e) but Chile will need to implement additional policies in order to be 1.5° compatible.

Our current policy emissions pathway includes the Unconventional Renewable Energy Law (Law 20.257/2008), the carbon tax (Law 20.780/2014), the results of electricity supply tenders as of December 2017, emissions reductions from the coal phase out plan, the updated Electromobility Strategy, and the energy efficiency law (Law 21.305/2021) (for more details, see Assumption section).

The main developments we have included in our latest assessment is an estimation of the impact of the full coal phase-out by 2040 in line with government plans (Gobierno de Chile, 2019; Ministerio de Energía, 2021g) where we now also included information on retrofitting certain coal-fired power plants to gas.

We have also updated the calculations of the electromobility strategy to account for the ban on sales of combustion engine (ICE) vehicles by 2035 (Ministerio de Energía, 2021c; Gobierno de Chile, 2022). We had previously already quantified the retirement of the first 11 coal-fired power plants—which we have slightly updated according to latest developments: the electromobility strategy and the energy efficiency law with potential emission savings of up to 28.6 MtCO2e. Additionally, the impact of the full coal phase-out by 2030 (Ministerio de Energía, 2022a)— currently under discussion— was assessed under a planned policies scenario (for more details, see Assumption section).

Further information on how the CAT rates countries (against modelled domestic pathways and fair share) can be found here.

Policy overview

Between 1990 and 2021, Chile’s emissions increased by 115% from 50 MtCO2e to 107 MtCO2e, excluding LULUCF. Looking at Chile’s current policies and expected GDP growth rates, we estimate that emissions will, on average, drop in 2022 to between 103-109 MtCO2e per year, excluding LULUCF, which represents a 16-23% increase above 2010 levels.

Although accounting for a drop from 2019 to 2020 due to COVID-19 in previous assessments, the actual emissions drop from 114 MtCO2e to 104 MtCO2e was significantly stronger than expected, which therefore leads to overall lower expected emissions in the following years. The rebound effect in 2021 remained limited (+3 MtCO2e, only reaching emissions levels of 2015), mainly because of the early phase-out of coal-fired power plants.

Our current policy emissions pathway includes the Unconventional Renewable Energy Law (Law 20.257/2008), the carbon tax (Law 20.780/2014), the energy efficiency law (Law 21.305/2021), the results of electricity supply tenders as of December 2017, emissions reductions from the retirement of the coal-fired power plants, the Electromobility Strategy, which sets out an action plan to achieve electrification of a 100% of public urban transport vehicle fleet by 2050 and a ban of cars with combustion engines in 2035.

With these policies and the COVID-19 assumptions, we therefore project that emissions will have peaked in 2019, have already begun to decline from 2021 levels in 2022, and the decline will accelerate after 2026. Our analysis suggests that Chile can meet its unconditional and potentially even its conditional NDC targets in 2030. If Chile goes ahead with the implementation of planned policies such as an early coal phase-out by 2030, it could be on track to being 1.5° compatible.

Chile’s overarching Climate Action Plan 2017–2022 was the instrument articulating climate change policy for all sectors (Ministerio del Medio Ambiente de Chile, 2017). In June 2022 it was replaced by the legally binding Climate Change Framework Law (21455) (Congreso Nacional de Chile, 2022). It includes the 2050 GHG neutrality target and recognises the NDC target.

For the first time, Chile has a legal framework that assigns responsibilities and strengthens the legal and institutional bases for implementing climate change mitigation and adaptation policies and moves towards a low emissions economy. It also presents a paradigm shift in Chile’s environmental policy, as climate action is now not only the responsibility of the environment ministry but is spread across 17 national ministries, as well as regional governments and municipalities, and even includes the private sector. The law went through public consultation between June and July 2019 and the idea of legislating the bill was approved by the Senate in August 2020.

In November 2021, at COP26 in Glasgow, Chile presented its long term energy strategy. Besides laying out the GHG neutrality target and a pathway to reach it, for the first time it laid out sectoral carbon budgets and allocated them to different ministries. These budgets are for the years 2020 to 2030 to meet the NDCs and for the GHG neutrality scenario.

Sectoral pledges

In Glasgow, a number of sectoral initiatives were launched to accelerate climate action. At most, these initiatives may close the 2030 emissions gap by around 9% - or 2.2 GtCO2e, though assessing what is new and what is already covered by existing NDC targets is challenging.

For methane, signatories agreed to cut emissions in all sectors by 30% globally over the next decade. The coal exit initiative seeks to transition away from unabated coal power by the 2030s or 2040s and to cease building new coal plants.

Signatories of the 100% EVs declaration agreed that 100% of new car and van sales in 2040 should be electric vehicles, 2035 for leading markets. On forests, leaders agreed “to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030”. The Beyond Oil & Gas Alliance (BOGA) seeks to facilitate a managed phase out of oil and gas production.

NDCs should be updated to include these sectoral initiatives, if they’re not already covered by existing NDC targets. As with all targets, implementation of the necessary policies and measures is critical to ensuring that these sectoral objectives are actually achieved.

| CHILE | Signed? | Included in NDC? | Taking action to achieve? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methane | Yes | No | Yes |

| Coal exit | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Electric vehicles | Yes | No | Yes |

| Forestry | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Beyond oil and gas | No | Not applicable | Not applicable |

- Methane pledge: Chile signed the methane pledge at COP26 on. Chile’s methane emissions have remained relatively stable in recent decades, accounting for 14 MtCO2e in 2021 (Gütschow and Pflüger, 2022). Methane is therefore responsible for 13% of total emissions (down from 23% in 1990). 6 MtCO2e come from the agriculture sector, accounting for almost half of the sectors emissions, and another 6.5 MTCO2e come from waste, accounting for almost all the emissions in the sector. The remaining 1.5 MTCO2e comes from the energy sector.

A 30% cut in methane emissions would therefore be translated into roughly 4 MTCO2e or 4% of total emissions, which would further increase Chile’s chances of meeting its NDC target. As Chile has not yet submitted an updated NDC since signing this pledge, it is not included in its NDC. Nevertheless, Chile’s NDC specifically states that methane is considered in the GHG target, and a includes measure on building new waste treatment plants that better manage methane by 2035. Chile’s former environmental minister Marcelo Mena is leading the Global Methane Hub, a hub which offers grants and technical support to implement the Global Methane Pledge.

- Coal exit: Chile agreed to the coal exit at COP26 and signed all clauses of the agreement. Chile had previously announced a complete phase-out of coal power by 2040, which is also prominently disclosed in its NDC. It has also pledged to build no new coal-fired power plants by signing this agreement. At COP26 Chile also signed up to both the No New Coal Power Compact that had been launched a few months earlier, and the Powering Past Coal Alliance.

In Chile, 30% of power generation comes from coal (IEA, 2022b). Although in decline since peaking at 41% in 2014 (IEA, 2022b), coal remains the dominant source in the electricity supply. Since signing the pledge and with a new government and cabinet, Chile is discussing an early, 2030 coal phase-out (Ministerio de Energía, 2022a).

- 100% EVs: Chile signed the declaration on accelerating the transition to 100% zero emission cars and vans at COP26, an obvious move as it had already adopted a target of 100% sales in EVs a month earlier, on 15 October 2021. This includes all light and medium duty vehicles as well as all vehicles from public transport. Chile has also announced that by 2045 buses and freight transport will follow (Ministerio de Energía, 2021c). Currently, more than a quarter of total GHGs comes from the transport sector, therefore, coupled with a decarbonisation of the power mix, these measures will have a significant impact on overall greenhouse gas reductions.

- Forestry: Chile signed the Leaders' declaration on forest and land use at COP26. While Chile has not updated its NDC since, forests and land already play a key role in its current NDC. In its NDC Chile commits to the sustainable management and recovery of 200,000 hectares of native forests and to afforest 200,000 hectares, which it estimates to represent GHG captures of around 3.9 to 4.6 MtCO2e annually by 2030. The NDC commits to reduce emissions in the forestry sector by 25% by 2030, to identify peatland areas and all other types of under a national inventory by 2025, and to develop standardised metrics to evaluate the capacity of wetlands (especially peatlands) for climate change adaptation or mitigation by 2030.

Energy supply

The updated Energy Strategy, titled Chile’s Energy Transition (also known as PEN for Política Energética Nacional), was published in March 2022 and replaces the previous 2050 Energy Strategy from 2017. It sets a long-term vision for energy planning in Chile and provides a roadmap including 66 targets covering various sectors. Targets have become substantially more ambitious than in the previous iteration: targets of the renewables share in electricity generation increased from 60% by 2035 to 80% by 2030 and from 70% to 100% by 2050 and, for the first time, set out new goals of a 100% renewable power system (Ministerio de Energía, 2015, 2022c). Chile’s renewable energy targets are therefore in line with global Paris Agreement’s long-term temperature goals, as the global power sector needs to rapidly transition to zero-CO2 emissions by around 2050 (Climate Action Tracker, 2016).

The Energy strategy went through a participatory process for its update in 2018 and 2019, which was followed by a document from the advisory committee that set out recommendations for the update of the National Energy Policy, originally released in May 2021. Notably, some measures and targets from the preliminary document have become even more ambitious in the final document (Ministerio de Energía, 2021a).

Chile is already moving towards meeting its renewable targets. In only six years (2014-2020), Chile has increased the generation capacity from solar and wind power five-fold (Ministerio de Energía, 2020a). Making progress towards the non-conventional renewables goal, in 2020, 24.8% of electricity generation was from non-conventional renewable sources1 (NCRE), putting Chile well on track to reaching its 2013 goal of 25% of installed capacity of NCREs by 2025 (Ministerio del Medio Ambiente, 2021).

A follow-up roadmap to the Energy Route 2018-2022 - the other key ministerial document, known as PELP (Planificación Energética de Largo Plazo) is being elaborated for the years 2023-2027 to accommodate for significantly stronger targets. It is under consultation and a preliminary document to allow for wider comments from the register of citizen participation was published in August 2021 (Ministerio de Energía, 2021h). It includes three modelled pathways, one based on current policies and assuming the NDC target for 2030 will be reached, and two more ambitious pathways aiming at GHG neutrality by 2050 and earlier.

Coal phase-out:

After more than a year of planning, in June 2019, Chile announced its plans to completely phase out coal by 2040 and aim for GHG neutrality by 2050 (Ministerio de Energía, 2019). However, around the same time, a new 375 MW coal-fired power plant in Mejillones (equivalent to about 1.8 TWh per year) started operations and two of Chile’s eight oldest coal power plants were closed (Electricidad, 2016; Engie, 2019; Tomás Gonzalez, 2019).

Since then, a shift in narrative has occurred and the coal phase-out has been progressing significantly faster than anticipated. The number of power plants to be shut by 2024 was increased to 11 in an updated plan released in 2020 (Ministerio de Energía, 2020c). In July 2021, Energy Minister Juan Carlos Jobet made an announcement that a total of 18 would be shut down or retrofitted by 2025, including the newly-opened Mejillones plant that will be retrofitted to operate as a natural gas plant. This early closure and repurposing would lead to 65% of Chile’s coal-power plants being closed by 2025.

This announcement has, however, not been officially confirmed and it is unclear which plants are included. Based on several announcements by utilities and the ministry it can be expected that an additional five coal-fired plants of a combined capacity of 1271 MW, representing an additional 22% of the total coal capacity in 2020 would be shut down by 2025 (Ministerio de Energía, 2021g).

The new phase-out plan is divided into two stages. First, between 2019 and 2024, Chile is closing the original eight, some of the oldest coal-fired power plants, plus an additional three plants of medium age (built 1996 to 2012). Combined, they are equivalent to 1,731MW, corresponding to 31% of Chile’s coal electricity capacity in 2020 and to nearly 7.7 MtCO2e/year of annual emissions by 2024 if the demand is replaced by renewable energy sources (Ministerio de Energía, 2021b). If electricity demand is replaced by gas-fired generation, emissions reductions by 2024 would be 4.3 MtCO2e/year. Chile will then phase out the remaining 17 plants, but has not yet specified a detailed schedule.

In August 2022, when the energy minister presented the new Energy Agenda 2022, he mentioned that discussions were ongoing for an even more ambitious plan to retire all coal power plants by 2030 (Ministerio de Energía, 2022a). This would bring Chile on track to being 1.5° compatible as phasing out all coal-fired power plants at the latest by 2032 would be an action compatible with the global sectoral benchmark for electricity sector under a scenario in line with the Paris Agreement for the Latin America region (Yanguas Parra et al., 2019).

We have estimated that closing all coal-fired power plants in Chile by 2040 – assuming lineal retirement between 2025 and 2040 – could lead to a cumulative emissions reduction potential between 17 MtCO2e/year to 28 MtCO2e/year by 2030 depending on which technologies substitute electricity generation (for more details see Assumption section).

As of October 2022, eight power plants with over 1 GW of installed capacity have successfully been retired, and a ninth plant is to follow by the end of the year. Although some were shut down six to 12 months after the planned date, Chile is successfully following its coal phase-out plan. Chile should, however, be careful when retrofitting its coal power plants with gas. Fossil gas should only play a minor role in Paris Agreement-compatible pathways (Climate Action Tracker, 2017) and there are risks around energy security as Chile imports most of its gas.

Energy efficiency law:

Another positive development was seen in February 2021 when the Energy Efficiency law (Ley de Eficiencia Energética, Law No. 21.305), which had previously been announced in the 2018–2022 Energy Route, was officially established as a legal framework for energy efficiency. The law aims to foster energy efficiency and covers the industry, mining, transport, and buildings sector, thereby reducing final energy consumption by 10% by 2030 and 35% by 2050. It will play a central role in reaching net zero emissions in 2050 and also in achieving mid-term targets. It claims to lead to a reduction of 28.6 MtCO2e by 2030 (Ministerio de Energía, 2021e). We have included this reduction in the current and planned policy projections: together with the coal phase-out it plays a key role in the expected reduction of Chile’s emissions.

Other laws and policies:

As a measure to foster decentralised renewable energy deployment, in early 2018, Chile reformed its Distributed Generation Law (also referred to as the “Net Billing” Law) (Law 20.571). The reform included a tripling of installed capacity threshold from 100 kW to 300 kW, which aims to support and promote larger projects of self-consumption of electricity (Ministerio de Energía, 2018). Electricity surplus can be fed into the grid to obtain discounts in the owner’s electricity bill. The reform establishes, that if an owner has more than one establishment, these discounts are also applicable for those electricity bills, otherwise, discounts from surplus can be accumulated.

This policy is neither quantified in the current policy scenario, nor the plan policy scenario, due to a lack of available data. In 2023, the National Strategy for Distributed Generation will be published. It will define explicit integration goals at the regional level, including the distributed generation "net billing". The strategy will be developed in a participatory manner and will be based on technical studies (Ministerio de Energía, 2022c)

Additionally, Chile has implemented a carbon tax of 5 USD/tCO2 for stationary sources (turbines or boilers above 50 MWth), which came into effect in 2017. Payments for 2017 began in April 2018 and accounted for more than 190 million USD (El Mercurio, 2018).

Chile’s most recent energy planning documents, the Mitigation Plan for the Energy Sector (referred to as Mitigation Plan) and the Energy Sector’s Long Term Strategy, already assume a decreasing share of coal electricity generation towards 2050 (Ministerio de Energía, 2017b, 2017c). Chile’s Mitigation Plan includes three different scenarios for the energy sector: current policies, 2050 Energy Strategy and additional effort. We have assessed the first two in our analysis as current and planned policies respectively, deducting estimations from policies coming after its publication. The main difference between these two scenarios lies in the assumptions of the long-term share of renewable energy and the coal phase-out.

In the current policy scenario, the renewable electricity share increases to reach around 59% by 2020 and then stalls. We consider the full coal phase-out plan: closing of the first eleven plants by 2024 and linear reduction of the remaining until 2040. The planned policy scenario considers a growing renewable energy generation share towards 2050, where it reaches 70% and the assumption of linear retirement of coal power plants by 2040. This difference is translated to higher GHG emissions in the current policy scenario, as electricity generation from gas is ramped up to satisfy growing demand. In a Paris Agreement-compatible pathway, however, unabated gas should play only a minor role in electricity generation and phase out completely by 2050 (Climate Action Tracker, 2017).

Both the current policy and 2050 Energy Strategy scenarios from the Mitigation Plan include substantial generation from hydro — which accounted for 19% of generation in 2021 (IEA, 2022b)(IEA, 2017), and is assumed to increase to 32% and 39% respectively in 2030. According to the 2050 Energy Strategy scenario from the Mitigation Plan, renewable energy generation goals in 2035 and 2050 are only to be met with a substantial contribution of hydro power generation. It is not clear how much of this share is large-scale hydropower. The construction of large hydropower projects in Chile is highly controversial, largely because of significant adverse environmental and social impacts. In 2014, Chile’s government overturned environmental permits for HidroAysén, a massive hydroelectric project in Patagonia, after a seven year campaign against it - the largest environmental campaign in Chile’s history (NRDC, 2016).

1Chile defines non-conventional renewable energy sources as wind, solar PV, geothermal, biomass, tidal, and hydro up to 20MW.

Industry

Chile is the world’s leading copper exporter, and the mining and industry sector is Chile’s largest consumer of final energy, accounting for 38% of energy consumption and 14% of total GHG emissions (Ministerio de Energía, 2022c).

Chile has established several targets to minimise emissions from the mining and industry sector in its energy strategy (PEN). They include:

- an emissions reduction target of 70% of direct GHG emissions from fuel use in the Industry and Mining sector by 2050 below 2018 levels,

- an improvement of energy intensity of large energy consumers by at least 25% in 2050 below 2021,

- a requirement that at least 90% of energy for heating and cooling in industry must come from sustainable sources by 2050,

- a goal of 100,000 new energy jobs by 2030, direct and indirect, from sustainable energy projects in new energy-related industries, and

- a requirement that 100% of medium and large companies in Chile must implement effective and monitorable energy efficiency and/or renewable energy measures.

These measures are also featured in Chile’s LTS (Gobierno de Chile, 2021; Ministerio de Energía, 2022c). The Chilean Copper Commission (COCHILCO) has carried out surveys and compiled data on GHG emissions and energy consumption, the Green Mining Roundtable was launched in 2019, and the Chilean Economic Development Agency (CORFO) has supported the deployment of hydrogen vehicles for mining, which is also covered in the green hydrogen strategy (Ministerio de Energía, 2020a). The Ministry of Mining is also developing the National Mining Policy 2050, in which environmental policy is set to play a central role (Ministerio del Medio Ambiente, 2021).

Among the contents of the new Energy Efficiency law approved in early 2021 is the promotion of energy management in the country's large consumers. These include all large companies with consumption over 50 Tcal per year (210 TJ/yr), cumulatively accounting for more than one third of the country’s consumed energy. These so-called consumers with energy management capacity have to implement an energy management system and will additionally have to prepare an annual public report on several indicators, including energy consumption and energy intensity (Ministerio de Energía, 2021e; Ministerio de Hacienda: Oficina de Partes, 2021)

Previously, an agreement between the government and the mining industry regarding energy efficiency was the “Cooperation Agreement”, under which mining companies should look for ways to use energy more efficiently, and the Ministry of Energy should support them (Government of Chile, 2016b).

Transport

The transport sector accounts for more than one third of Chile’s total final energy consumption (37% ), almost the same as industry, and accounts for 26% of total GHG emissions, as 99% of the sector’s energy consumption is from imported fossil fuels (Ministerio de Energía, 2022c).

As with other sectors, Chile has also established a number of targets to minimise emissions from transport sector in its energy strategy (PEN). Most prominently this includes a requirement that by 2035 100% of the sales of new light and medium vehicles are zero emissions. We estimate that this measure alone could lead to a reduction of 1.1 MTCO2e.

Other goals include a 40% reduction in direct GHG emissions from the use of fuels in the transport sector (including land, sea and air transport) by 2050 compared to 2018 (20% by 2040), 100% zero emission vehicles in public transport and urban public transport by 2040, 60% of zero emissions private and commercial vehicles by 2050 (Ministerio de Energía, 2022c). These measures are also featured in Chile’s LTS (Gobierno de Chile, 2021)

In December 2017, Chile published its Electromobility Strategy, which sets out a goal and action plan towards achieving a 40% share of electric passenger vehicles as well as a 100% electrified public transport by 2050 (Ministerio de Energía, 2017a). Chile’s Energy Route 2018-2022 also sets out a short-term goal of a 10-fold increase in EVs in 2022 (compared to 2017 levels) (Ministerio de Energía, 2021i).

The market share of EVs remains low but it has doubled in 2021 to 0.19% of vehicles sold, and public charging infrastructure is limited, with only 480 (up from 350 in 2020) units in 2021 (compared to e.g., 51,000 in Germany) (IEA, 2022a). While at a low level, the sector is growing: EV sales increased 15-fold in five years, thus an exponential trend can be observed (IEA, 2022a).

Chile is also already beginning to implement actions towards achieving the aforementioned targets. In 2020, for example, Chile registered 400 electric buses, doubling its stock to more than 800 and reaching the target set for 2020. This makes Chile the clear Latin American leader in terms of size of electric bus fleet (IEA, 2021a).The Chilean government also launched its first interurban electric bus, which operates the 85km route between Santiago and Rancagua and installed a 50 kW DC fast charger at the Turbus Terminal in Santiago for this purpose (Ministerio de Energía, 2021i). In July 2022 Chile also opened its first electric bus factory (Reuters, 2022).

The Energy Efficiency law also targets the transport sector. It establishes energy efficiency standards for imported vehicles, and government subsidies are offered for electric taxis and home charging points. Furthermore, it aims to ensure interoperability of the EV charging system facilitates the access and connection to the charging network, and it gives powers to establish energy efficiency standards for vehicles (Ministerio de Energía, 2021d). The green hydrogen strategy, which was published in late 2020, also emphasises decarbonisation in the transport sector. Amongst other sectors (mining and agriculture), the transport sector is specifically targeted in the hydrogen plan, at first mainly for heavy and long-distance transportation, and later also to replace liquid fuels in land transportation (Ministerio de Energía, 2020a)

Chile’s electromobility target, and the first measures that have been taken, are a step in the right direction. It is especially great to see how the decarbonisation of the transport sector is also included in new strategies and laws, such as the Energy Efficiency law and the Green Hydrogen Strategy.

Although the 2035 ban of non-EVs is a great step into the right direction, additional policies, especially targeting private car ownership, are needed to meet these targets, and global decarbonisation benchmarks, which foresee having only zero emission cars on the road by 2050 to be compatible with limiting temperature to 1.5°C (Climate Action Tracker, 2016). For the development of an integral policy making framework for transport, it is of great importance to consider social and economic consequences of the different policy options. The total emissions reduction potential of transport electrification depends significantly upon the decarbonisation of the electricity supply used to charge vehicles.

Buildings

Buildings consume 23%, almost a quarter, of the country's total energy with a significant part of this is used for heating and are responsible for 7% of Chile’s GHG emissions (Comisión Nacional de Energía, 2021; Ministerio de Energía, 2022c). It is therefore not surprising that the buildings sector is a central part of the new Energy Efficiency law.

The law establishes that residential buildings, public buildings, commercial buildings and office buildings must have an energy rating to be commercialised: this is applicable to construction and real estate companies as well as housing and urban planning services. As with appliances such as refrigerators, the energy efficiency label allows people to have better information when renting or buying homes. The label must be included in all sales advertising by companies (Ministerio de Energía, 2021e).

As with other sectors, Chile’s energy strategy (PEN) also established a number of targets to minimise emissions from the buildings sector, including:

- a requirement that 10% of existing homes have a specific standard for thermal regulation by 2050, which should point towards net zero energy buildings;

- that 100% of new public buildings are "zero net energy consuming" by 2030, considering optimal energy performance of heating, hot water, cooling and lighting systems;

- that 100% of new residential and non-residential buildings are “zero net energy consumption” by 2050 (Ministerio de Energía, 2022c).

Even prior to the updated PEN and the Energy Efficiency law, Chile has been pursuing strategies for the buildings sector such as a National Strategy for Sustainable Buildings, which includes energy, water, waste and health goals. The government also incentivises energy efficiency in public buildings (Government of Chile, 2016a).

Under the Law no. 20.571/2016, Chile aims to incentivise the use of solar heating through tax cuts for developers who implement this technology (Ministerio de Energía, 2017b). A draft law currently debated in the Senate aims to promote an energy efficiency rating system for buildings – “Calificación Energética de Viviendas (CEV, in Spanish)”. This rating issued by the Ministry of Housing and Urbanism will be required for new residential buildings to be commercialised.

Chile has over 20 Mha of natural forest and therefore has great natural sinks, particularly in the south of the country (Global Forest Watch, 2022). Although having lost 2.2 Mha, or 10%, in the last 20 years (Global Forest Watch, 2022). on average Chile’s LULUCF sinks over the last 20 years were roughly 2/3 of other emissions. Chile should work toward maintaining this LULUCF sink.

The LULUCF sector has been a major sink in Chile, with GHG net emissions usually ranging from -48 to -78 MtCO2e from 1990 to 2020, with the exception of 2017. In 2018, CO2 removal from LULUCF accounted for 64 MtCO2, thus being able to compensate for more than half to countries CO2 emissions (112 MtCO2).

Whereas the emission reductions from LULUCF sinks remained relatively stable until 2016, the value was reduced to -12 MtCO2e in 2017, which can directly be attributed to some of Chile’s worst wildfires in modern history that swept across the country (Ministerio del Medio Ambiente, 2020). This shows how vulnerable these sinks are to extreme weather events, which are expected to increase in numbers. CO2e removal through LULUCF is also a central part of Chile’s strategy to become GHG neutral in 2050, it is therefore extremely important to assure that forests keep acting as sinks and do not turn into emission sources.

Chile’s 2020 NDC references the National Strategy for Climate Change and Vegetation Resources (ENCCRV), established since 2013 by the Ministry of Agriculture (MINAGRI), through the National Forest Corporation (CONAF), as one of the main tools in reaching the different targets on mitigation related to LULUCF, along with regulations and instruments granting incentives for forest owners to preserve or create new forests. Further, the NDC states that its afforestation target should be in line with Law Nº20.283 on Native Forest Recovery and Forest Promotion, under which afforestation is undertaken only in lands without vegetation and does not allow for substitution of native forests (Government of Chile, 2020a).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter