Policies & action

Chile’s current policies are almost sufficient when rated against modelled domestic pathways. The “Almost sufficient” rating indicates that Chile’s climate policies and action in 2030 are not yet consistent with the 1.5°C temperature limit but could be, with moderate improvements. If all countries were to follow Chile’s approach, warming could be held below—but not well below—2°C.

Chile’s upper end of its current policy projections sits in the “Insufficient” range, meaning a lack of implementation of mitigation policies and increased fossil gas consumption from retrofitting coal plants could result in a worse rating for Chile.

According to our assessment, emissions under Chile’s currently implemented policies would reach 104–106 MtCO2e (excl. LULUCF) by 2030 (8–10% below 2021 levels). The CAT estimates that Chile reached peak emissions in 2021, ahead of the 2025 target in its NDC. However, this emissions level is still insufficient to reach Chile’s 2030 NDC target (95 MtCO2e), let alone on a 1.5°C trajectory. Chile will need to implement additional policies in order to be 1.5°C compatible.

Chile has continued to shut down coal plants according to its phase-out plan. Over 1.2 GW of coal capacity from 11 plants has been retired since 2019 and an additional nine units are planned to retire or convert to fossil gas by 2026. Up to five of these units may be retrofitted for gas. The 2040 coal phase out date was restated in the Decarbonisation Plan and Energy Sectoral Mitigation Plan, but President Boric announced his intention to advance the phase-out to 2035 or earlier. An early coal phase-out, where electricity generation is replaced by renewable sources rather than fossil gas, could significantly impact Chile’s current policies pathway and bring it considerably closer to a 1.5°C trajectory.

Renewable energy curtailment due to transmission and grid integration challenges is a considerable barrier to accelerating the coal phase-out, and must be addressed to ensure the reliable replacement of coal generation with renewable sources. While fossil gas is considered a “transition fuel” by the Chilean government, the CAT estimates it needs to be completely phased out by 2035 to remain on a global 1.5°C pathway: fossil gas is still a fossil fuel. Therefore, Chile must be careful when repurposing its coal-fired plants to avoid the risk of carbon lock-in and stranded assets. Chile’s recent stance on fossil gas increasingly reflects these considerations: all new energy projects are now required to be assessed under the Framework Law for Climate Change and their compatibility with Chile’s NDC and GHG neutrality targets.

The transport sector makes up a significant share of Chile’s total GHG emissions, especially as its energy consumption continues to increase. The Electromobility Strategy, Energy Efficiency Law, and ban on new ICE vehicle sales by 2035 are key policies expected to accelerate the low-carbon transportation transition. While there has been some progress around public transport electrification and vehicle fuel standards, Chile’s EV sales have only just exceeded 2%. More could be done to encourage EV uptake and decrease energy demand, for instance by reforming diesel fuel subsidies and incentivising a modal shift in transportation, so that Chile does not fall behind on its transport electrification targets.

Maintaining the LULUCF sink is an important component of Chile’s climate targets, which is threatened by the increased frequency and severity of wildfires related to climate change. In 2023, the LULUCF sector almost became a net emissions source due to destructive wildfires. While Chile has ambitious commitments for reforestation and sustainable forest management in its NDC, the pace of implementation has been far too slow, and stronger policies to support reforestation and forest management are needed. At the same time, Chile should avoid relying on LULUCF sinks for its targets and prioritise cutting fossil fuel emissions in other sectors.

Further information on how the CAT rates countries (against modelled domestic pathways and fair share) can be found here.

Policy overview

Between 2010 and 2023, Chile’s emissions increased by 24%, from 88 MtCO2e to 110 MtCO2e, excluding LULUCF. When considering Chile’s current policies, we estimate that Chile’s emissions already peaked in 2021 at a level of 115 MtCO2e. According to our assessment, Chile’s emission levels in 2030 under current policies will be between 104–106 MtCO2e/year (excl. LULUCF). Our analysis suggests that Chile will not meet its conditional nor unconditional NDC targets in 2030 under current policies, or be 1.5° compatible.

Compared to our previous assessment, the lower end of Chile emissions under current policies has increased but the range has narrowed. The recent Sectoral Mitigation Plans represent an important step towards reaching Chile’s 2030 NDC target. However, recent analyses suggest that the outlined measures alone may not be enough to achieve Chile’s NDC, and questions remain about their implementation, particularly with the pace of coal retirements and scale of gas reconversions, the transmission of renewable energy, and the electrification of the transport and industry sectors. It may not fully account for potential challenges and uncertainties including infrastructure constraints, energy security, and technology deployment timelines (Centro de Energía, 2025).

Chile’s climate legislation and policy framework has substantially strengthened in recent years. In June 2022, Chile passed the Framework Law on Climate Change (LMCC) (21455) (Congreso Nacional de Chile, 2022). It includes the 2050 GHG neutrality target and recognises the NDC target, making them legally binding.

As a result, Chile now has a legal framework that assigns responsibilities and strengthens the legal and institutional basis for implementing climate change mitigation and adaptation policies across all sectors and moving towards a low emissions economy. It also presented a paradigm shift in Chile’s environmental policy, as climate action is now not only the responsibility of the environment ministry but is spread across 17 national ministries, as well as regional governments and municipalities, and even includes the private sector.

By early 2025, in accordance with LMCC mandates, all relevant ministries have finalised and had their sectoral mitigation plans approved, marking a significant step towards the implementation of Chile’s 2030 NDC target (CR2 & Centro de Derecho Ambiental, 2025). Each plan outlines specific short- and medium-term mitigation measures, their estimated emissions reduction potential in line with their sectoral budgets, and the associated investment needs.

Chile’s key climate policies include the Energy Efficiency Law (Law 21.305/2021), a legal framework aiming to reduce energy consumption across the power, transport, buildings, and industry sectors. It also includes the coal phase-out, where all of Chile’s coal-fired units (28) are expected to retire or be retrofitted by 2040. Chile is on track with its 2040 coal phase-out plan, meeting its goal of retiring 11 plants by 2024, and nine of the remaining coal-fired units expected to be retired or retrofitted around 2026. However, the eight remaining coal plants have yet to make a firm commitment: it is still possible for them to continue operating until 2040 (Global Energy Monitor, 2025).

President Boric announced his intention to advance the coal phase-out to 2035 (Djunisic, 2025). While the Ministry of Energy’s new Decarbonisation Plan reaffirms the 2040 date, it opens the door for potential advancement based on the reliability and renewable integration of the electricity system (Ministerio de Energía, 2025). An earlier coal phase-out would have a positive impact on Chile’s current policy trajectory, though its scale depends on the extent to which coal capacity is replaced with generation from renewable energy sources. The CAT estimates that choosing to retrofit coal plants with fossil gas could lead to at least 3 MtCO2e less emission reductions in the short-term compared to retiring coal-fired units and using renewable electricity sources and can lead to carbon lock-in risks and stranded assets.

The Electromobility Strategy guides climate policy in the transport sector and sets out an action plan to electrify 100% of the urban public transport vehicle fleet by 2050 and ban the sale of new cars with combustion engines in 2035. EV sales have substantially grown percentagewise but remain low at just over 2% of vehicle sales in 2024 (IEA, 2025). Chile’s diesel tax is relatively low, which may not incentivise a shift towards cleaner transport alternatives, and a sizable portion of Chile’s current EV subsidies benefit consumers who would have purchased a low-emissions vehicle regardless of support (OECD, 2025).

Chile introduced a carbon tax for stationary sources (Law 20.780/2014), although its price was considered too low to result in meaningful emissions reductions in industrial or power plants. The Decarbonisation Plan outlines a gradual increase in the carbon tax, aiming to reach USD 35/tCO2 by 2030 and USD 80/tCO2 by 2040, representing a significant improvement in Chile’s carbon pricing framework (Ministerio de Energía, 2025).

Under the Framework Law, Chile has finished revising its Article 6 framework, which establishes the legal and technical infrastructure for the verification and transferring of GHG emissions reduction or absorption certificates. Chile signed a bilateral agreement with Switzerland in 2023 for the latter to finance emissions reduction projects in exchange for Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs). In October 2025, Chile authorised the first project under the regime, involving converting a coal-fired boiler with a biomass system in the Ñuble region (Velev, 2025).

Chile has also signed a carbon credit agreement with Singapore. These deals risk selling emission reductions that are relatively inexpensive or would have occurred anyway, leaving Chile with fewer and more costly options to increase its own mitigation. Finance generated through the purchase of carbon credits (ITMOs) under Article 6 should not be counted as climate finance. ITMO transactions are designed to help the buying country achieve its targets, while the selling country (in this case, Chile) must make a corresponding adjustment that effectively makes the achievement of its own target more difficult. Giving away its opportunity to cut emissions at home is unlikely to benefit Chile.

Chile plans to establish safeguards to ensure additionality and traceability, alongside a clear list of eligible activities that prioritises projects with higher technical or financial barriers. However, especially for Chile, where current policies are not sufficient to meet its NDC, selling reductions now may be at odds with the additionality objective, which is to ensure that the use of carbon credits drive real and additional emissions reductions.

For more information on the promise and pitfalls of Article 6 mechanisms, see the recent CAT briefing here.

Power sector

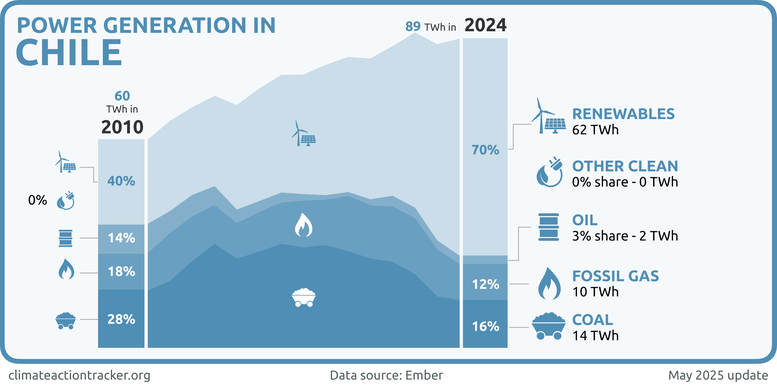

The power sector is one of Chile's largest emitting sectors, accounting for 25% of total emissions, or 34% of energy sector emissions. The general share of electricity production sources in 2024 was around 64% of renewables, including 30% hydropower, 22% solar, 11.5% wind power, and 0.6% of other renewables, with the remainder consisting of 16% coal, 12% fossil gas, and 3% other fossil fuels (Ember, 2025a).

Fossil fuels made up roughly one-half to two-thirds of electricity generation from 2000 to the mid-2010s, with hydropower accounting for the remaining share. Hydropower generation has dropped since the early 2000s, which can be attributed to both drought conditions and the uptake of other renewable sources (i.e. wind and solar), and has since accounted for 20–30% of the power mix (Revista Energética de Chile, 2022).

Chile’s energy policy framework has significantly expanded in recent years. The updated Energy Strategy (also known as PEN for Política Energética Nacional) was published in 2022, setting Chile’s overarching, long-term vision for energy planning and provides a roadmap including 66 targets across sectors. Renewable electricity generation targets became substantially more ambitious: the targeted renewables share in electricity generation increased from 60% by 2035 to 80% by 2030 and from 70% to 100% by 2050, setting out the new goal of a 100% renewable power system for the first time (Ministerio de Energía, 2015, 2022b). According to the CAT’s power sector benchmarks, Chile should achieve a more ambitious renewables share between 96–98% in 2030 and decarbonise by 2035 to be aligned with a global 1.5°C pathway (Climate Action Tracker, 2023).

Building on this, the Energy Sector Mitigation Plan (Plan Sectorial de Mitigación de Energía) translates Chile’s goals into specific mitigation measures. The Ministry of Energy has also finalised its Decarbonisation Plan (Plan de Descarbonización). It reaffirms the 2040 coal phase-out date but leaves the door open for an earlier retirement date if system reliability and renewable integration are sufficient (Ministerio de Energía, 2025). President Boric also announced his intention to introduce a bill to advance the coal phase-out date to 2035 or earlier (Djunisic, 2025).

While fossil gas will continue to play a role in Chile’s electricity mix in the near term, the new plans signal a clear shift away from continued fossil gas production and imports. They prioritise accelerated investments in renewables deployment, energy storage, grid expansion, and demand-side management, and takes a more cautious management approach to existing gas infrastructure. Critically, all new energy projects will also be required to be evaluated for their alignment with Chile’s Climate Change Framework Law and short and long-term climate targets and have clear decarbonisation plans to limit lock-in (Ministerio de Energía, 2024b, 2025).

To complement its focus on renewables expansion, the Decarbonisation Plan additionally outlines a strengthening of Chile’s carbon tax, set to gradually increase to USD 35/tCO2 by 2030 and USD 80 tCO2 by 2040.

A follow-up roadmap to the Energy Route 2018–2022, the other key ministerial document, known as PELP 2023–2027 (Planificación Energética de Largo Plazo) was released in 2023. It includes three modelled pathways, one based on current policies that assumes that Chile will achieve its 2030 NDC target, and two more ambitious pathways aiming at GHG neutrality by 2050 and earlier. These scenarios have fed into the recent Decarbonisation and Sectoral Mitigation plans.

The Energy Efficiency Law (Ley de Eficiencia Energética, Law No. 21.305) was officially established as a legal framework for energy efficiency in February 2021. The law aims to foster energy efficiency and covers the industry, mining, transport, and buildings sectors, thereby reducing total final energy consumption by 10% by 2030 and 35% by 2050 in addition to various sectoral-level targets. It will play a central role in reaching net zero emissions in 2050 and also in achieving mid-term targets, and claims to lead to a reduction of 28.6 MtCO2e by 2030 (Ministerio de Energía, 2021c). Several of Chile’s new sectoral plans explicitly build on the law, to align short and medium-term mitigation actions with its targets or introduce intermediary measures.

Chile has also implemented a carbon tax of 5 USD/tCO2 for stationary sources (turbines or boilers above 50 MWth), which came into effect in 2017 (El Mercurio, 2018). In 2021, the tax covered 32.5% of GHG emissions. As of 2022, Chile’s carbon tax is applicable to all “large emitters” (>25 ktCO2e/year) without any sectoral exclusions (OECD, 2024). However, Chile’s carbon tax was considered to be relatively ineffective due to its low prices. The Decarbonisation Plan outlines an increase in the carbon tax to reach 35 USD/tCO2 by 2030 and 80 USD/tCO2 by 2040 (Ministerio de Energía, 2025).

Both current policies and 2050 Energy Strategy scenarios from the Mitigation Plan include considerable generation from hydro — which accounted for 30% of generation in 2024 (Ember, 2025a). The construction of large hydropower projects in Chile is highly controversial, largely because of significant adverse environmental and social impacts. In 2014, Chile’s government overturned environmental permits for HidroAysén, a massive hydroelectric project in Patagonia, after a seven year campaign against it – the largest environmental campaign in Chile’s history (NRDC, 2016).

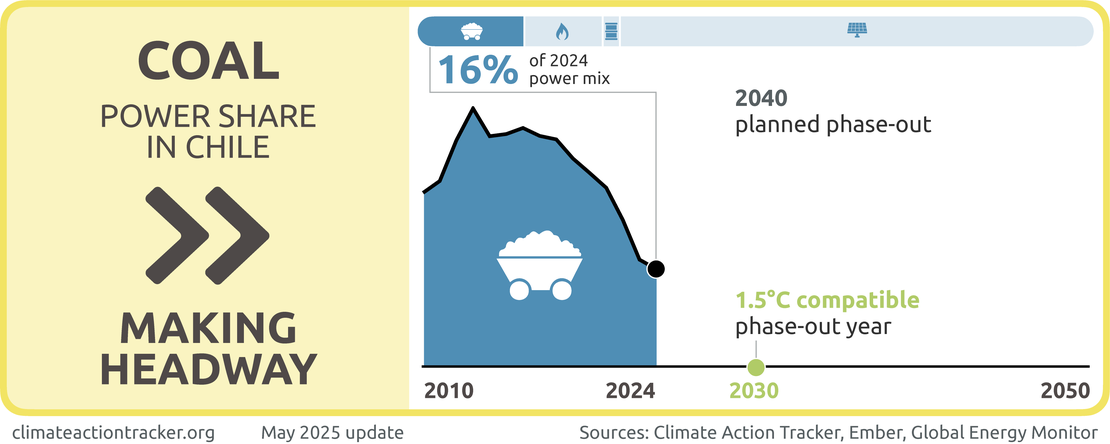

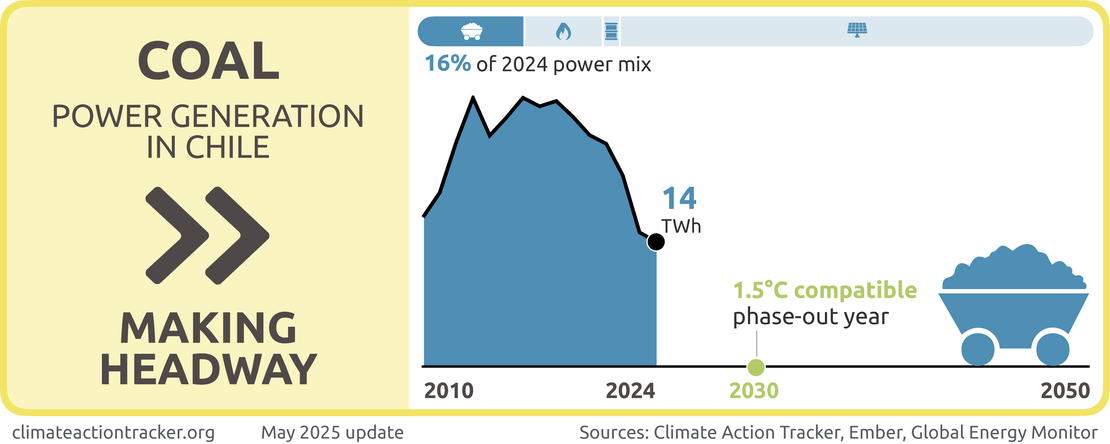

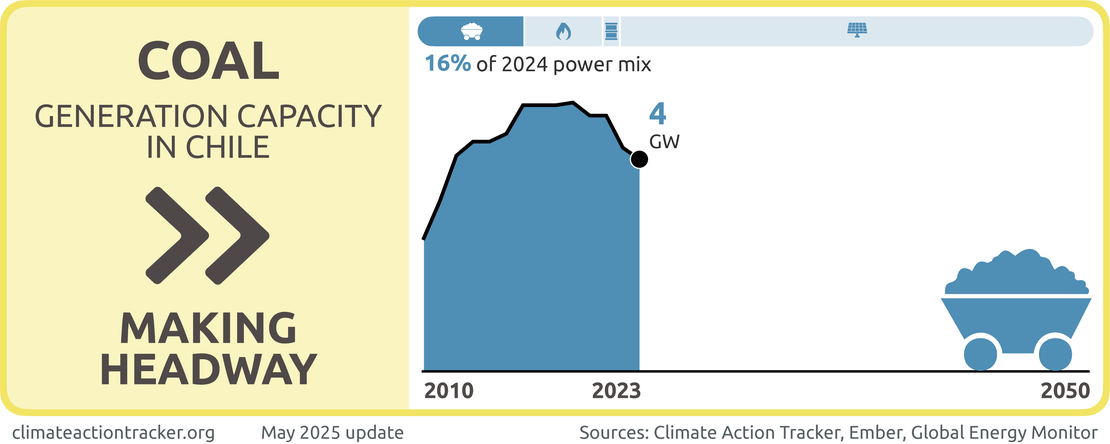

Coal

Chile is “making headway” in phasing out coal, with progress moving faster than expected. Coal generation has decreased in the last five years, falling from 28 TWh in 2019 to 14 TWh in 2024. Over the same period, the share of coal in Chile’s electricity mix also declined significantly—from 34% in 2019 to 16% in 2024 (Ember, 2025a).

In June 2019, Chile announced its plans to completely phase out coal by 2040 and aim for GHG neutrality by 2050 (Ministerio de Energía, 2019). In line with this announcement, Chile signed the coal exit agreement and all of its clauses at COP26 and also prominently disclosed it in its updated NDC.

Since then, the coal phase-out has been progressing considerably faster than anticipated. As of July 2025, Chile has successfully retired 11 power plants with around 1.7 GW of installed capacity, achieving the 2024 goal. In April 2024, the Norgener 1 and Norgener 2 units (totaling 276 MW) in Tocopilla were disconnected much earlier than their scheduled December 2025 date (Global Energy Monitor, 2025; Pizzoleo, 2024).

The Ministry of Energy’s Decarbonisation Plan was recently finalised, reconfirming the 2040 coal phase-out date while outlining incentives to accelerate retirements and reconversions in this decade (Ministerio de Energía, 2025). It also estimates that 70%, or about 20, of Chile’s coal plants will be available for retirement or reconversion (with gas) around 2026 (Ministerio de Energía, 2023c).

The accelerated coal phase-out plan, while a very positive development, would still leave Chile’s eight remaining coal-fired units (representing 1.9 GW of coal capacity) without any concrete retirement commitments. At the moment, they are not obligated to stop operating until 2040, meaning that Chile could still use coal to meet its electricity demand until then (Global Energy Monitor, 2024). According to the CAT, an effective coal phase-out by 2030 would align Chile with a 1.5°C global pathway. An early coal phase-out would also help bring Chile’s policies considerably closer to a 1.5°C trajectory if coal plants are completely retired instead of retrofitting them into fossil gas plants (Climate Action Tracker, 2023).

In August 2022, when the energy minister at the time presented the new Energy Agenda 2022, he mentioned that discussions were ongoing for an even more ambitious plan to retire all coal power plants by 2030 (Ministerio de Energía, 2022c). While these discussions stalled in the following years, President Boric announced his intention to submit a bill to Congress to advance the coal phase-out target to 2035 or earlier (Djunisic, 2025). The Decarbonisation Plan also notes that the 2040 coal phase out date could be reevaluated based on system reliability and the progress in renewable energy grid integration (Ministerio de Energía, 2025).

The first part of Chile’s Just Transition Strategy puts a focus on the retirement of coal plants. It aims to promote new job opportunities and investments, avoid significant increases in electricity rates, and develop new industries in communities that would be affected by the closure of coal plants. The strategy emphasises a participatory process with affected stakeholders and its implementation will be monitored by an Interministerial Committee (Ministerio de Energía, 2021a).

Although some plants were shut down six to 12 months after the planned date, Chile’s coal phase-out plan has gone beyond its initial expectations. Chile should, however, be careful when retrofitting its coal power plants with fossil gas, which is a fossil fuel. The International Energy Agency (IEA) and recent scientific analyses highlight that there is no room for investment in new oil, gas, and coal activities if global warming is to be limited to 1.5°C (Green et al., 2024).

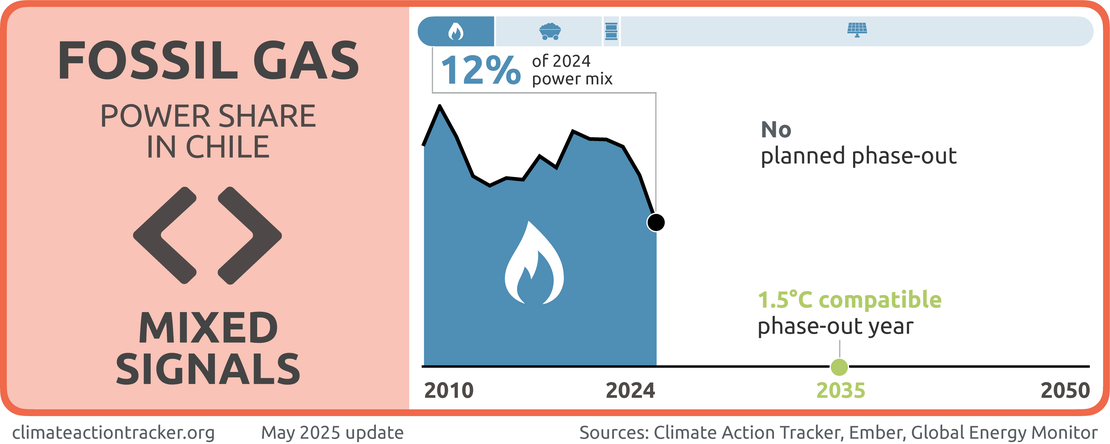

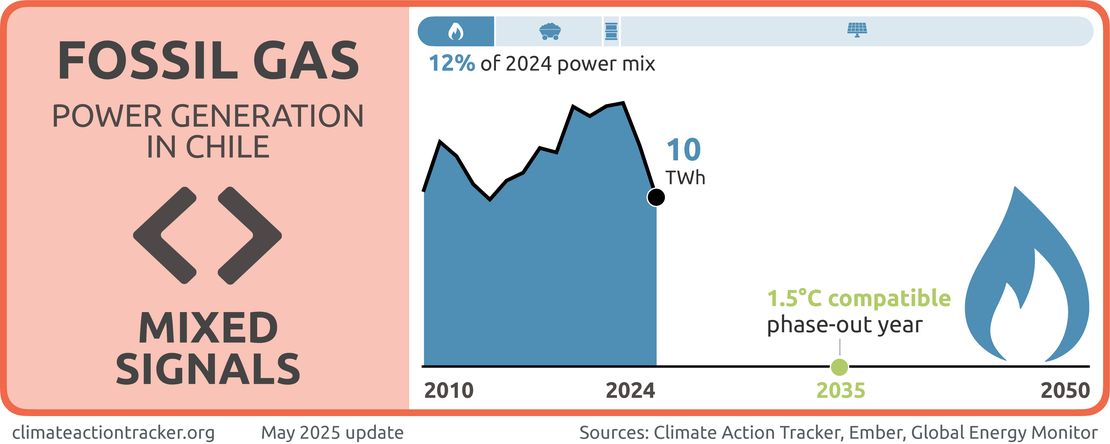

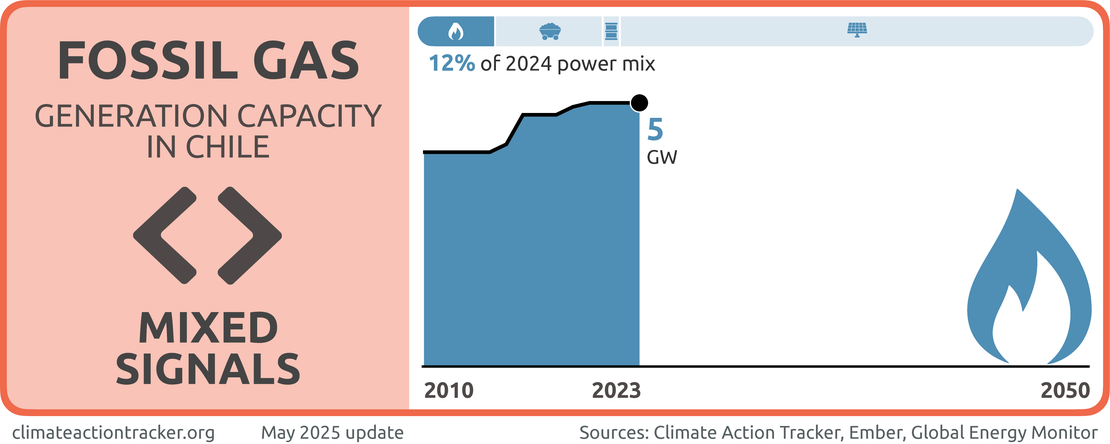

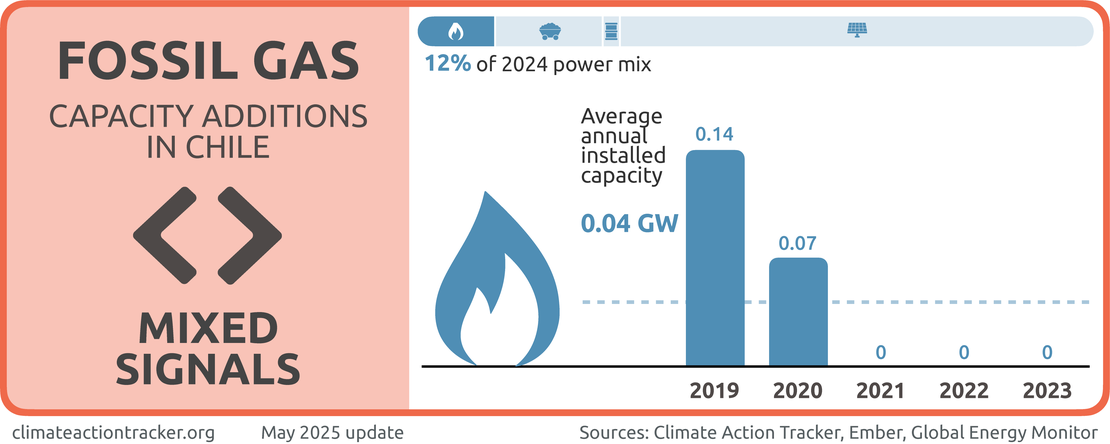

Fossil gas

Chile is sending “mixed signals” on fossil gas. While the share of fossil gas in electricity generation has declined from 15–20% over the past decade to 12% in 2024, there are no plans to phase it out in the short term (Ember, 2025a). Chile’s Plan de Descarbonización, finalised in October 2025, acknowledges a potential short-term increase in fossil gas use as several coal plants are converted to gas in place of complete retirement (Ministerio de Energía, 2025). Chile produces less than 20% of its total gas supply, and primarily relies on imports (Deza, 2024).

Neither the Plan de Descarbonización nor the Sectoral Mitigation Plan set a phase-out year for fossil gas. Both plans, however, highlight the need to limit long-term gas lock-in through prioritising investments in renewable energy generation, improved storage, and demand management over new fossil gas capacity. The Sectoral Plan further mandates a review of Chile’s gas production and import policies by 2026 to assess their consistency with national decarbonisation and energy security goals (Ministerio de Energía, 2024b, 2025).

In line with these strategies, Chile has introduced compatibility criteria under the Climate Change Framework Law (2022) that requires new public and private investment projects to be reviewed for their alignment with Chile’s climate targets and have a credible strategy for future decarbonisation to reconversion to green technologies. While fossil gas remains a part of Chile’s electricity mix in the medium-term, the new plans mark a decisive shift away from continued expansion and towards cautious management and decline.

Fossil gas should only play a minor role in Paris Agreement-compatible pathways: according to the CAT’s power sector benchmarks, fossil gas should only make up 1–4% of Chile’s electricity generation in 2030 and should be fully phased out by 2035 to be aligned with a global 1.5°C pathway (Climate Action Tracker, 2023).

Some private operators continue to explore fossil gas production. In February 2024, a Chilean energy company signed a deal with a California-based gas technology company to boost production by up to 200% (Geiger, 2024). There is potential for this deal to face increased scrutiny under Chile's new compatibility criteria. There is no room for new investment in fossil fuel activities if global warming is to be limited to 1.5°C (Green et al., 2024).

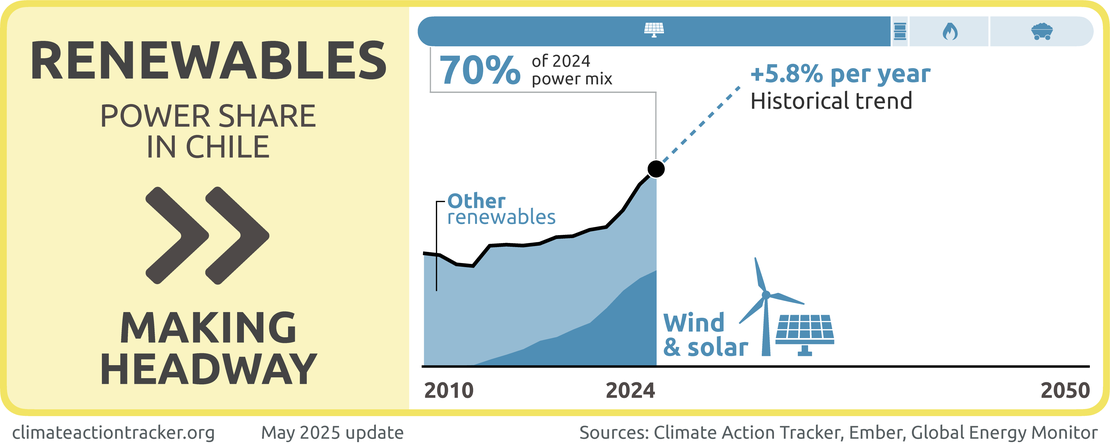

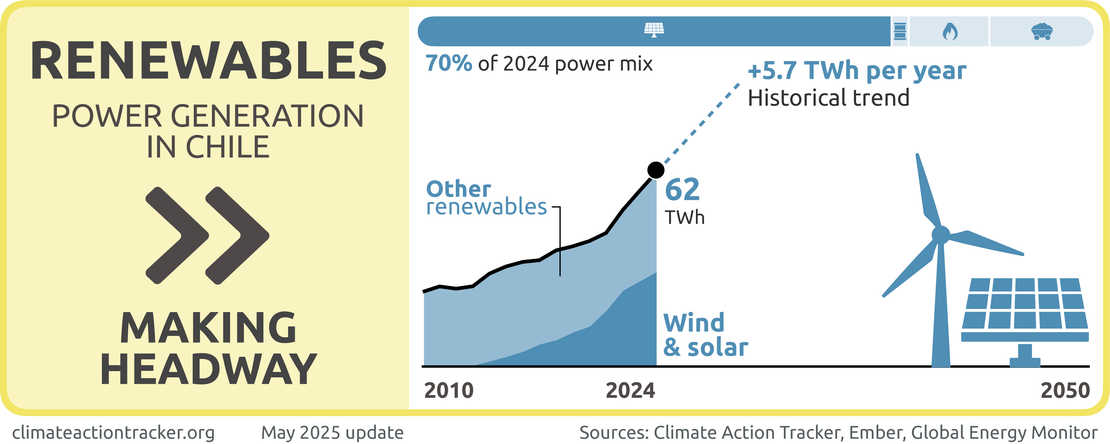

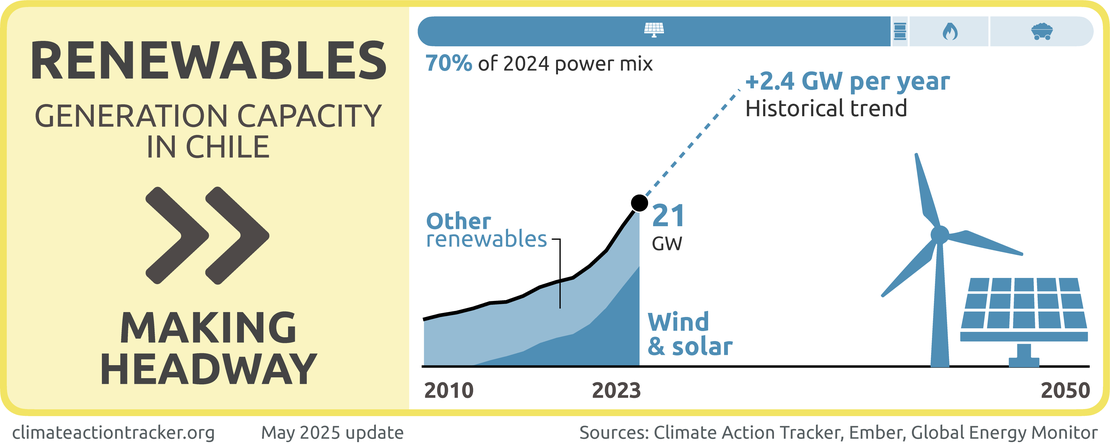

Renewables

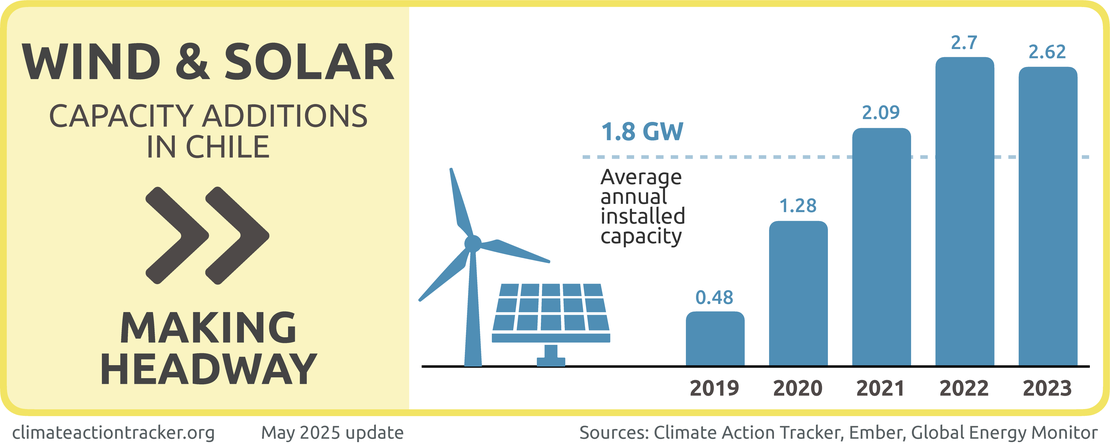

Chile is “making headway” in renewable energy deployment, with around 70% of its electricity derived from renewables in 2024, up from 46% in 2019. Renewable generation has significantly increased over the last five years, jumping from 39 TWh in 2019 to 62 TWh in 2024 (Ember, 2025a).

Hydropower has historically accounted for a considerable share of Chile’s electricity production, accounting for almost 50% of electricity generated in 2000, but its share has decreased to 30% in 2024 (Ember, 2024). While wind and solar power made up less than 0.1% of electricity generation in 2013, their shares have significantly increased to reach 12% and 22% of total electricity production, respectively, in 2024.

Chile has set out a target of achieving an 80% share of renewable electricity generation by 2030 and 100% by 2050. The Plan de Descarbonización and energy Sectoral Mitigation Plan reaffirms these targets. According to the CAT’s power sector benchmarks, Chile should achieve a more ambitious renewables share between 96–98% in 2030 and decarbonise by 2035 to be aligned with a global 1.5°C pathway (Climate Action Tracker, 2023).

Despite its progress, Chile faces significant challenges with renewables curtailment, having to reduce its wind and solar electricity generation by 19% (5,642 GWh) in 2024 due to transmission challenges. Chile’s unique geography has posed challenges for the transmission and storage capacity of renewable electricity. Without curtailment, the share of solar and wind in electricity generation in 2024 could have increased from 34% to 41% (Ember, 2025b). The national electric companies’ Hoja de Ruta, a roadmap for power sector development, emphasises that Chile’s grid must be fully prepared for large-scale renewables integration by 2030 and that investments in transmission, storage, and grid-balancing should be prioritised.

Various laws to foster renewable energy growth and improve transmission have been passed or are in the legislative process. The 2022 Law on Energy Storage and Electromobility (Law 21.505), will enable storage systems that are separate from generation facilities to be paid for providing energy to the grid, especially in times in high demand. One of the main objectives of this law is to reduce the reliance on coal by improving the energy security of the electricity system (Ministerio de Energía, 2022a). Chile is expected to achieve its 2030 battery energy storage system (BESS) target of 2GW by next year, with an additional 5GW expected to be added between 2025–2030 (Tourino, 2025).

The Energy Transition Law, enacted in December 2024, will serve as an intermediary step for the structural reforms needed to achieve Chile’s carbon neutrality goal. Its three main pillars are promoting the efficient development of transmission projects, enabling the buildout of key infrastructure, and encouraging the competitive advancement of energy storage (Lagos & Yuraszeck, 2024). The Bill Promoting Renewable Energies in the Electricity Matrix aims to establish renewable energy quotas for new electricity contracts, gradually increasing until reaching 60% in 2030 (Medinilla, 2023).

As a measure to foster decentralised renewable energy deployment, in early 2018, Chile reformed its Distributed Generation Law (also referred to as the “Net Billing” Law) (Law 20.571). The reform included a tripling of installed capacity from 100 kW to 300 kW, which aims to support and promote larger self-consumption projects (Ministerio de Energía, 2018). The law was further updated in 2024 to expand incentives for renewable self-consumption, increase the maximum allowable installed capacity, and streamline the grid integration processes for distributed generation.

Green hydrogen

Chile’s National Green Hydrogen Strategy, published in late 2020, set goals for Chile to produce the lowest-cost green hydrogen worldwide by 2030 and become a top three global exporter by 2040 (Ministerio de Energía, 2020a). Hydrogen plays a significant role in Chile’s carbon neutrality strategy, and is expected to contribute a quarter of the necessary emission reductions in 2050 (Gobierno de Chile, 2024).

The strategy emphasises green hydrogen’s role in the decarbonisation of the transport, mining, and agriculture sectors. One of its first objectives is to use green hydrogen in heavy and long-distance transportation, and later to also replace liquid fuels in land transportation and aviation. Green hydrogen and its derivatives are also expected to be incorporated in the industry sector and produce green ammonia for low-carbon fertiliser production (Ministerio de Energía, 2020a). The potential of hydrogen is also highlighted in the Ministry of Energy’s Sectoral Mitigation Plan (PSMyA Energía), which includes a target for green hydrogen to make up 15% of final non-electric energy consumption by 2035 and 70% by 2050 (Ministerio de Energía, 2024b).

To operationalise the Hydrogen Strategy, Chile published its Green Hydrogen Action Plan in April 2024, which outlines short-term measures to promote green hydrogen production and utilisation (Gobierno de Chile, 2024). A significant number of actions are focused around developing the enabling infrastructure for the green hydrogen industry and its regulatory and financial support.

In the transport sector, a public-private partnership is in the process of developing Chile’s first locally-made hydrogen bus, which is expected to be piloted by the first half of 2025 (Gobierno de Chile, 2023c). The plan also explores converting thermal plants to run on hydrogen or hydrogen-based fuels through co-combustion or blending (Gobierno de Chile, 2024).

Industry

Chile is the world’s leading copper exporter, and the mining and industry sector is its largest consumer of final energy, accounting for 36% of energy consumption in 2023 and approximately 18% of energy-related emissions (IEA, 2024a). In 2021, 44% of mining electricity consumption came from renewable sources, and it is estimated that it will reach 62% in 2025 (Gobierno de Chile, 2025).

The National Mining Policy 2050, developed by the Ministry of Mining, was approved in early 2023, and includes several objectives related to GHG emissions and environmental considerations. Notably, it includes a target to reduce emissions from large mining operations by at least 50% by 2030, and to become a carbon-neutral industry by 2040 (Gobierno de Chile, 2023a). The Chilean government and the Mining Council signed a public-private agreement aiming to achieve carbon neutrality in the mining industry by 2050, reflecting a slightly longer time horizon than presented in the Policy (Ministerio de Economía, Fomento y Turismo, 2025).

The Mining Policy also outlines an objective for 90% of electricity contracts to come from renewable sources by 2030 and 100% by 2050. While it also specified a zero-emissions fleet plan to be released by 2025 and implemented by 2030, the strategy appears to be delayed (Gobierno de Chile, 2023a). Along with being responsible for the monitoring and implementation of the above, the Ministry of Mining is also directed to establish emissions targets for scope 1, 2, and 3 that comply with the 2030 target.

Chile’s 2035 NDC includes additional mining-specific emissions reduction targets, aiming for emissions reductions of 57% in open-pit copper mines, 74% in underground copper mining, and 52% in other mining activities (Gobierno de Chile, 2025).

Several other targets to minimise emissions from the mining and industry sector are included in Chile’s Energy Strategy (PEN). These measures are also featured in Chile’s LTS (Gobierno de Chile, 2021; Ministerio de Energía, 2022b). They include:

- an emissions reduction target of 70% of direct emissions from fuel use in the industry and mining sector by 2050 below 2018 levels,

- an improvement of energy intensity of large energy consumers by at least 25% in 2050 below 2021,

- a requirement that at least 90% of energy for heating and cooling in industry must come from sustainable sources by 2050,

- a goal of 100,000 new energy jobs by 2030, direct and indirect, from sustainable energy projects in new energy-related industries, and

- a requirement that 100% of medium and large companies in Chile must implement effective and monitorable energy efficiency and/or renewable energy measures.

As with all relevant ministries under the Framework Law on Climate Change, the Ministry of Mining has finalised its Sectoral Mitigation Plan. It outlines measures to align the mining sector with Chile’s 2030 NDC such as electrification, green hydrogen adoption, energy efficiency improvements such as advancing minimum energy performance standards, and renewable energy contracts and distributed generation (Ministerio de Minería, 2024).

The mining sector is showing progress, but it remains unclear whether the pace of implementation is sufficient for Chile to meet its sectoral targets. Renewable energy use continues to expand, and could account for over 70% of the sector’s electricity consumption by 2027 (OECD, 2025). The state-owned mining company Codelco has signed power purchase agreements totaling 1.8 Twh/year, which could allow 85% of its energy supply to come from renewable sources in 2026 (Reuters, 2024). Codelco also recently reported that reduced its Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions by 27% by 2024 compared to 2019 levels, while it has targeted a 70% reduction by 2030 (Codelco, 2025).

Mining companies play an important role in meeting these targets. The Chilean Copper Commission (COCHILCO) has carried out surveys and compiled data on GHG emissions and energy consumption, the Green Mining Roundtable was launched in 2019, and the Chilean Economic Development Agency (CORFO) has supported the deployment of hydrogen vehicles for mining (Ministerio de Energía, 2020a). The deployment of green hydrogen and its derivatives in the mining sector is a key component of Chile’s Green Hydrogen Strategy and Action Plan (Gobierno de Chile, 2024).

Implementation of energy efficiency measures is advancing under the 2021 Energy Efficiency Law, which requires all large companies with consumption over 50 Tcal per year (210 TJ/yr), cumulatively accounting for more than one third of the country’s consumed energy, to implement an energy management system that covers at least 80% of their emissions. They will also have to prepare an annual public report on several performance indicators, including energy consumption and energy intensity (Ministerio de Energía, 2021d; Reglamento Sobre Gestión Energética de Los Consumidores Con Capacidad de Gestión de La Energía y de Los Organismos Públicos, a Que Se Refiere La Ley N° 21.305, 2021). As of 2022, 92% of copper operations were following the Energy Efficiency Law with 72% already having energy management systems in place (OECD, 2025).

Transport

The transport sector accounted for a third of Chile’s total final energy consumption (33%) in 2022 and 27% of its total GHG emissions, considering 99% of the sector’s energy consumption is from imported fossil fuels (IEA, 2025). Emissions from transport have considerably increased in recent years, growing by 18% compared to 2016, and have now become Chile’s single largest source of emissions.

As with other sectors, Chile has established a number of targets to minimise emissions from the transport sector in its energy strategy (PEN). The most prominent target is that 100% of new light and medium-duty vehicles sales must be zero emissions vehicles by 2035. In line with this target, at COP26 Chile signed the declaration on accelerating the transition to 100% EVs. While Chile is still behind in meeting this target, EV sales have shown some growth, reaching 2% of total vehicle sales in 2024, up from less than 1% in 2023. For Chile to achieve its transport electrification ambitions, it needs additional policies to support EV uptake.

Chile’s Ministry of Transport published its Sectoral Mitigation Plan in January 2025, which focuses on concrete short and medium-term actions to help Chile achieve its 2030 NDC target. It outlines six key mitigation measures: electrifying public transport in Santiago and other regions, the electrification of taxis and “colectivos”, the expansion of train and metro, and cycling systems to promote modal shift. The implementation of these measures is expected to contribute to emissions reductions of at least 3.43 MtCO2e by 2030 (Ministerio de Transportes y Telecomunicaciones, 2025).

In December 2017, Chile published its Electromobility Strategy, which sets out its long-term vision and action plan towards achieving a 40% share of electric passenger vehicles as well as a 100% electrified public transport fleet by 2050 (Ministerio de Energía, 2017a). The PEN updated these targets in 2022 and made them more ambitious, aiming for 100% zero emission vehicles in public transport and urban public transport by 2040, and 60% of private and commercial vehicles to be zero emissions by 2050 (Ministerio de Energía, 2022b).

Other transport goals include a 40% reduction in direct GHG emissions from the use of fuels in the sector (including land, sea, and air transport) by 2050 compared to 2018 (20% by 2040). Seeing as Chile’s sectoral emissions budget for 2020–2030 allows for transport emissions to increase the most relative to other sectors, achieving this long-term target may be difficult (OECD, 2025).

Chile is already beginning to implement actions towards achieving these targets. As of April 2024, Chile has reportedly reached over 2,500 electric buses in its public transport system, representing 38% of its total fleet (Carrara, 2024). Electric buses now represent around one-fifth of total bus sales in the country (IEA, 2024b). While the market share of EVs remains low, sales have grown to 2% in 2024, up from 0.8% in 2023, and have increased ten-fold in the past five years, indicating a rapid upward trend. However, EVs still make up only 0.3% of the total car fleet. Public charging infrastructure is somewhat limited but growing, with only 1,810 units (up from 1,070 in 2022) units in 2023 (compared to e.g., 51,000 in Germany) (IEA, 2025).

In addition to promoting renewables in the energy matrix, the Law on Energy Storage and Electromobility (21.505) includes measures to encourage EV uptake. The law includes temporary exemptions or reductions for driving permit fees for electric and hybrid vehicles, thus matching those of ICE vehicles, and enables battery EVs to connect to the grid and store energy (Ministerio de Energía, 2022a).

Building on the Electromobility Strategy, in 2023, Chile presented its Roadmap for the Advancement of Electromobility. This plan contains concrete measures to 2026 aimed at accelerating the EV transition and addressing Chile’s current EV infrastructure gap. Its main pillars are building a robust public infrastructure charging network, promoting public transportation and decentralisation in priority regions, and improving EV education and road safety (Gobierno de Chile, 2023b).

The Energy Efficiency Law also targets the transport sector. It establishes energy efficiency standards for imported vehicles, which came into effect in 2024, and government subsidies are offered for electric taxis and home charging points. It aims to ensure interoperability of the EV charging system, facilitates access and connection to the charging network, and allows the Ministry of Transport to establish energy efficiency standards for vehicles (LEY NÚM. 21.305: SOBRE EFICIENCIA ENERGÉTICA, 2021). Standards for medium-duty vehicles are planned to take effect in 2026, followed by heavy duty standards in 2028 (Agora Verkehrswende, 2025).

Building on its Green Hydrogen Strategy, the government has also presented its Sustainable Aviation Fuels 2050 Roadmap (SAF 2050). The roadmap sets out a goal of achieving 50% of SAF use in aviation by 2050 by promoting local, decentralised production of new energy sources. including biofuels and green hydrogen (Ministerio de Energía, 2024a).

Chile’s electromobility targets, initial implemented measures, and the 2035 ban of non-EV sales are a great step in the right direction, especially since they are integrated into new strategies and laws such as the Energy Efficiency Law and Green Hydrogen Strategy. However, additional policies, especially targeting private car ownership, are needed to meet both these targets and global decarbonisation benchmarks, which foresee having only zero emission cars on the road by 2050 to be compatible with limiting temperature to 1.5°C (Climate Action Tracker, 2016). For the development of an integral policy making framework for transport, it is of great importance to consider social and economic consequences of the different policy options. The total emissions reduction potential of transport electrification also significantly depends on the decarbonisation of the electricity supply used to charge vehicles.

Buildings

Buildings consumed about a quarter of the country's total energy in 2023, with a significant share of this used for heating, and were responsible for approximately 8% of Chile’s total emissions (excl. LULUCF) in the same year (Comisión Nacional de Energía, 2021; IEA, 2024a; Ministerio de Energía, 2022b). It is therefore not surprising that the buildings sector is a central part of the Chile’s cross-sectoral Energy Efficiency Law.

Both the Ministry of Energy and Ministry of Housing and Urban Planning’s Sectoral Mitigation include new measures under the framework of the Energy Efficiency Law. This includes updates to thermal regulations (OGUC) for residential buildings and buildings used in education and healthcare expected in November 2025. They will establish stricter requirements for building envelopes to reduce heat loss in winter and prevent overheating in the summer (de Vicente, 2025). These plans also establish new mid-term goals, including to reduce final energy consumption in buildings by 10% by 2030 and achieving 30% of average energy savings by 2035 from retrofitting existing housing stock.

The Energy Efficiency Law requires that residential, public, commercial, and office buildings obtain an energy rating to be commercialised (i.e. put on the market): this is applicable to construction and real estate companies as well as housing and urban planning services. Similar to appliance labels, the building energy efficiency label informs buyers and tenants about a property’s energy performance (Ministerio de Energía, 2021c). It is based on the Calificación Energética de Viviendas (CEV), Chile’s national energy rating framework established in 2011, and is also integrated into voluntary national building sustainability certifications (Ministerio de Energía, 2021b). As of October 2025, the enforcement of these requirements was strengthened: CEVs are strictly mandatory for all new construction projects, and the housing energy rating must be disclosed in all promotional and sales material. The Energy Efficiency Law also states that companies with high energy consumption (over 50 tcal) must annually report their energy consumption and energy intensity. It also introduces an Energy Management System (EMS), covering at least 80% of total energy consumption that includes an energy efficiency action plan, goals, and performance indicators. In 2023, the list of companies that must apply these regulations was published (Ministerio de Energía, 2023b).

As with other sectors, Chile’s energy strategy (PEN) also established a number of targets to minimise emissions from the buildings sector, including:

- a requirement that 10% of existing homes have a specific standard for thermal regulation by 2050, which should point towards net zero energy buildings;

- that 100% of new public buildings are "zero net energy consuming" by 2030, considering optimal energy performance of heating, hot water, cooling and lighting systems;

that 100% of new residential and non-residential buildings are “zero net energy consumption” by 2050 (Ministerio de Energía, 2022b).

So far, the implementation of these goals has been relatively slow. A recent study suggests that a higher ambition for thermal housing regulations to 35% of homes by 2035, may be necessary to align Chile with a 1.5°C-compatible pathway (OECD, 2025). Pilot projects for net-zero public buildings are underway, however, progress is still early and limited.

Even prior to the updated PEN and the Energy Efficiency Law, Chile has been pursuing strategies for the buildings sector such as the National Strategy for Sustainable Construction (ENCS), its main objectives being to incorporate sustainability criteria into buildings and infrastructure and construction processes to reduce the sector’s energy consumption, reduce GHG emissions, and promote renewable energy use in construction (Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo, 2013).

In addition to being revalidated, the ENCS is currently in the process of updating its sustainability criteria to respond to new national and international commitments (Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo, 2024). The government has also presented its new programme for Sustainable Consumption and Production 2024–2030, which identifies sustainable construction as one of its priority areas, and provides an institutional framework to support to ongoing ENCS update (Ministerio de Economía, Fomento y Turismo, 2024).

Building on these developments, Chile has begun making progress implementing sustainable building practices. The country currently has 291 buildings with sustainability certifications and more than 560 others in the process of certification. The Burgos Net Zero facility become the first building in Latin America to achieve the Net Zero Energy standard (Reyes, 2025).

Chile has also implemented different financial incentives and support programmes to improve building energy efficiency. For instance, under Law no. 20.571/2016, Chile aims to incentivise the use of solar heating through tax cuts for developers who implement this technology (Ministerio de Energía, 2017b). In 2023, the energy and housing ministries introduced subsidies for families to implement solar heating, photovoltaic systems, thermal insulation, and to replace wood-burning heaters (Ministerio de Energía, 2023a).

Methane

Chile signed the methane pledge at COP26. Chile’s methane emissions have remained relatively stable in recent decades, accounting for 16 MtCO2e in 2023 or 15% of total emissions (down from 26% in 1990) (Gütschow & Pflüger, 2023). The agriculture (39%) and waste (50%) sectors account for most of Chile’s methane emissions, with a smaller share coming from the energy sector (11%). A 30% cut in methane emissions would therefore translate into roughly 5 MtCO2e or almost 5% of total emissions in 2023, which would further increase Chile’s chances of meeting its NDC target.

Chile’s 2035 NDC references the Global Methane Pledge and includes a national target to peak methane emissions by 2025. However, Chile’s new goal to reduce methane emissions by 10% by 2035 falls short of the pace implied by the pledge. The new NDC highlights the National Organic Waste Strategy, which aims to increase organic waste recovery from 1% to 66% by 2040, as a key measure to support methane reduction efforts (Ministerio del Medio Ambiente, 2023b). Chile’s former environmental minister Marcelo Mena is also leading the Global Methane Hub, a hub which offers grants and technical support to implement the Global Methane Pledge.

Chile has over 20 Mha of tree cover and therefore has significant natural sinks, particularly in the south of the country (Global Forest Watch, 2024). Although it has lost 2.39 Mha of this cover, or 12%, in the last 20 years, on average Chile’s LULUCF sinks made up roughly two-thirds of its other emissions (Global Forest Watch, 2024). Net removals from the sector have slightly decreased from -83 MtCO2e in 1990 to -57 MtCO2e in 2022 but have fluctuated around similar levels since the early 2000s, with the exception of 2017 and most recently 2023.

The government’s preliminary estimates for 2023 emissions indicate that LULUCF removals sharply dropped to just -3 MtCO2e (Ministerio del Medio Ambiente, 2024). This can be linked to widespread wildfires in the summer of 2023, where over 400 kha of forest burned (OECD, 2024). A similar event occurred in 2017, where the LULUCF sector became an emissions source of 15 MtCO2e due to the worst wildfires in Chile’s modern history that swept across the country (Ministerio del Medio Ambiente, 2020). These wildfires show how vulnerable these sinks are to extreme weather events, which are expected to increase in frequency and severity. CO2 removal through LULUCF is a central part of Chile’s strategy to become GHG neutral in 2050, targeting a sink of -65 MtCO2e in its net zero year (2050). Therefore, it is extremely important to assure that forests keep acting as sinks and do not turn into emission sources.

At COP26, Chile signed the Leaders' Declaration on Forest and Land Use. The LULUCF sector plays a key role in its current target. In its NDC, Chile committed to a 25% emissions reduction in the forestry sector by 2030, the sustainable management and recovery of 200,000 hectares of native forests, and the afforestation of an additional 200,000 hectares. These actions are estimated to account for 3.9 to 4.6 MtCO2e of annual removals by 2030 (Gobierno de Chile, 2020). The NDC also commits to identifying peatland and other wetland areas in the national inventory and evaluating their capacity for climate change adaptation or mitigation by 2030.

Chile’s 2035 NDC reiterates its 2030 commitments and introduces additional targets for the post-2030 period, though on a limited scale. Each year from 2031 and 2035, Chile aims for an additional 10,000 hectares of forest land under sustainable management and to reforest an additional 5,000 hectares. These actions are expected to deliver an additional 0.4–0.5 MtCO2e in GHG removals by 2035 (Gobierno de Chile, 2025).

However, Chile’s current pace of implementing its LULUCF targets is considerably slower than what is needed to meet its commitments under its NDC. Between 2020 and 2022, only 2 kha were reforested, meaning an additional 198 kha of land would need to be reforested in the next eight years. Similarly, sustainable forest management activities have occurred on only 35 kha of native forests and if this trend continues, Chile will only reach 15% of its target by 2030 (Cortés Lehuei, 2024). Thus, stronger policies to promote reforestation and sustainable native forest management are needed for Chile to meet its LULUCF targets set under its NDC. At the same time, Chile should limit the role of LULUCF sinks to meets its climate targets, given the high risk of carbon loss through deforestation or natural disturbances and should instead prioritise emissions reductions in all other sectors, especially fossil fuels.

Chile’s new NDC continues to reference the National Strategy for Climate Change and Vegetation Resources (ENCCRV), established in 2013 by the Ministry of Agriculture (MINAGRI) through the National Forest Corporation (CONAF), as one of the main tools in reaching the different targets on mitigation related to LULUCF, along with regulations and instruments granting incentives for forest owners to preserve or create new forests. Further, the NDC states that its afforestation target should be in line with Law N°20.283 on Native Forest Recovery and Forest Promotion, under which afforestation is only undertaken in lands without vegetation and cannot be a substitution of native forests (Gobierno de Chile, 2020).

Chile was the first Latin America country to join the World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF). In January 2025, it received its first payment of USD 5.1 million for reducing 1.03 MtCO2e in emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+), and can access up to USD 26 million for 5.2 MtCO2e in emissions reductions efforts. Chile also benefits from complementary support under the Green Climate Fund (GCF), which has provided over USD 60 million in technical assistance, equipment, and capacity building to communities, many of which led by women Indigenous peoples, to support activities such as fire prevention, post-fire forest restoration, sustainable biomass and timber use, and forest-based tourism (World Bank Group, 2025).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter