Current Policy Projections

Economy-wide

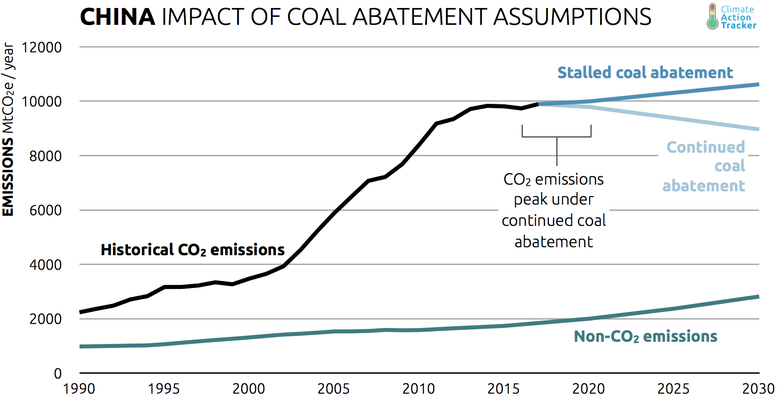

In the CAT current policy projections, China will reach a GHG emissions level (excl. LULUCF) of between 11.8 and 12.0 GtCO2e in 2020 and 11.7–13.4 GtCO2e in 2030. A total of 9.0–9.2 GtCO2e in 2020 and 8.2–9.8 GtCO2e in 2030 are energy-related CO2 emissions. This is an increase in total GHG emissions of 2%–4% above 2015 levels by 2020 and 2%–16% by 2030.

This means that according to our assessment, China will meet its 2020 pledge and its NDC targets, but still be slightly above current emissions levels. The projected increase in emissions is mostly related to emissions of gases other than CO2, because in the lower range of the current policy projections, overall CO2 emissions peak between 2015 and 2020.

China is implementing a range of policies in most sectors. Most significant is its commitment to limit coal use, and a strong increase of renewable and low-carbon energy. In December 2017, China announced a new national emissions trading system, which will initially apply only to the power sector, but may be expanded to other sectors in the future. The overall emissions impact of the system is not yet clear, as many operational details are still to be shared, including the start date and the level and distribution of emissions allowances (Jotzo et al., 2018).

Energy supply

Controlling coal consumption

China’s National Action Plan on Climate Change mentions—in the context of the “reasonable control of the total coal consumption”—a target to increase the share of gas in the total primary energy supply to 10% in 2020. The Energy Development Strategy Action Plan (2014–2020) further defines the “reasonable control of the total coal consumption” as limiting coal to a maximum of 4.2 billion tonnes by 2020. Recently, the cap on coal has been quantified as a maximum 58% share of coal in total primary energy consumption by 2020 (Lin, 2017)

In February 2015, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) and the Finance Ministry released the 2015–2020 action plan on the efficient use of coal, aiming at decreasing coal use by 160 million tonnes in the next five years (Xinhua 2015). The 13th Five Year Plan period (2016–2020) introduced more coal-related targets, such as a ban on new coal-fired power plants until 2018, and a cut in production capacity of coal (Enerdata, 2016). To combat air pollution, China is shutting down some coal-fired power plants, for example in Beijing, where the last remaining coal fired power plant was shut down in 2017 and replaced with gas power plants (Xinhua, 2017). However, according to the National Energy Administration, other plants are being retrofit to use coal more efficiently (NEA, 2018). The Chinese government is also pushing a switch from coal to gas in homes and factories, and gas consumption rose 15% in 2017 over 2016 levels (Aizhu, 2018).

On the production side, China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), has issued, in its government work report, targets to cut coal production capacity by 150 million tonnes in 2018. This may not lead to immediate reductions in output, due to overcapacities in the sector (Platts, 2018).

It has been claimed that overall coal consumption in China may already have peaked in 2013, as it dropped 2.9% in 2014, by 3.7% in 2015 and by 4.7% in 2016. This appears to be mainly due to two factors: a decline in growth in the construction and manufacturing sector as a result of the overall slowdown of China’s economic growth, as well as a continued policy drive to lower coal use in order to reduce air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions (Korsbakken & Peters, 2017; Qi, Stern, Wu, Lu, & Green, 2016). Coal consumption rose 0.3% in 2017, largely driven by increased electricity demand, but stayed below its 2013 peak (IEA, 2018).

In our current policy projections (see Assumptions below), we have included these most recent trends on coal abatement (Korsbakken & Peters, 2017; National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2017b). Based on optimistic or pessimistic assumptions of further coal abatement in the future, we then calculate the 2020 and 2030 levels of energy-related emissions. This gives a range of emissions under this assumed peaking of coal consumption in 2013. CO2 emissions from other sectors, cement and industry, as well as non-CO2 emissions, were assumed to follow present policies. This results in absolute emission levels of 11.7–13.4 GtCO2e excl. LULUCF in 2030.

Our assessment suggests that continued abatement of coal consumption could soon stop the rise in China’s CO2 emissions. Others have noted the same possibility and the large associated uncertainties (Peters, 2017). The actual timing of a true peak in CO2 emissions will likely hinge on developments in the next couple of years.

Renewable energy targets

In its 13th Five Year Plan period (2016–2020), China set the following targets for non-fossil capacity installed by 2020: 340 GW of hydropower capacity, 200 GW of wind power, 15 GW from biomass and 120 GW of solar power, as well as 58 GW of nuclear capacity (NDRC, 2016). As it turned out during 2017 that the solar target would be reached much earlier than 2020, the National Energy Administration adjusted it upward to 213 GW by 2020. Wind power, at current growth rates, would also reach an installed capacity of about 264 GW by 2020 (Yan & Myllyvirta, 2017). Investment in renewable energy in China in 2017 reached $126.6 billion USD, accounting for 45% of global investment in renewables (Frankfurt School-UNEP Centre/BNEF, 2018).

In 2013, Bloomberg New Energy Finance anticipated an increase of non-fossil capacity of a similar order of magnitude, more than 800 GW between 2010 and 2030 (Bloomberg New Energy Finance, 2013), which would add up to more than 1100 GW in 2030.

A report by the Energy Research Institute illustrates a scenario of a high penetration of renewable energy, reaching a share of more than 50% of electricity generation in 2030. While the research is a scenario analysis and not linked to any policies, the report still shows that renewable energy is seen as an important pillar of energy supply in China, which can significantly contribute to a long-term sustainable energy system (Energy Research Institute of the National Development and Reform Commission, 2015).

Renewable capacity in China is suffering from very high rates of curtailment as grid integration lags behind installation. In some provinces, curtailment of wind energy may be as high as 40% (Gordon & Hove, 2016). We have assumed default load hours calculated from the World Energy Outlook to apply to newly-installed renewable capacity, but this may be an optimistic assumption given such high rates of curtailment.

China reportedly surpassed its 2020 targets on solar PV deployment in 2017, leading the NEA to roughly double its solar capacity target for 2020 in response. Wind energy deployment is also on track to exceed its 2020 target by roughly a quarter (NEA, 2017; Yan & Myllyvirta, 2017). We estimate that if these 2020 deployment levels are achieved for solar PV and wind power, this could lead to further emission reductions by 2020 and 2030 of roughly 100 MtCO2. These numbers have not yet been included in the current assessment, but will be part of future CAT assessments of China’s current policies.

Transport

The uptake of electric vehicles (full and hybrid) is happening faster and faster, with over 600,000 electric vehicles sold in China in 2017—a 2017 market share of 2.7% and nearly half of global electric vehicle sales (Pontes, 2018). At China’s 13th National People’s Congress in March 2018, the Chinese parliament extended tax subsidies on new energy vehicles for an additional three years (Platts, 2018). As of 2019, automakers will need to amass credits for the sale of new energy vehicles, making up 10% of annual sales in 2019 and 12% in 2020. Manufacturers could earn multiple credits for a single vehicle, meaning that the actual percentage of new energy vehicles sales could be lower than 10% of annual sales in 2019 and still comply with the standards (Shirouzu & Jourdan, 2017). New energy vehicles are a priority sector in China’s “Made In China 2025” policy initiative, which aims to comprehensively upgrade Chinese industries. For the auto industry, the strategy foresees fuel consumption standards of 5 ltrs/100 km in 2020, one million units of new energy vehicles sold in 2020, and world leadership in batteries and electric motors (China Daily, 2015).

Industry

China’s energy intensity targets are supported by policies to reduce energy consumption. In the industrial sector, the TOP 1000 enterprises programme has led to effective energy savings, and has been extended to 10,000 installations. There is also an increasing number of efficiency standards for appliances, buildings and cars.

In the steel sector, the 2018 government work plan set a target to cut production capacity by 30 million tonnes in 2018, which may not affect output due to overcapacities in the industry (Platts, 2018).

In 2014 and 2015, China also started to tackle non-CO2 emissions, most notably HFC emissions. The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) is investing in demonstration projects for the controlled disposal of HFCs in industry. Further, it is setting up a reporting and monitoring instrument for F-gases for industrial companies (ESCO Committee of China Energy Conversation Association 2015). The NDC document also states targeted reductions of HCFC22 production of 35% by 2020 and 67.5% by 2025 below 2010 levels, and also refers to controlling HFC23, which is largely a by-product of HCFC-22 production. According to our initial assessment, this could lead to reductions of HFC23 of 230 MtCO2e in 2020 and 300 MtCO2e in 2025, which would help further bend the emissions curves downwards. As there is no clear regulation that assures implementation of these targets, we have not included these reductions in the current policy projections. However, they are an important stepping stone towards tackling this sector (EIA 2015).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter