Policies & action

China's suite of sectoral 14th FYPs set out a range of mitigation measures to prepare the country for a post-coal transition but is unable to counter growing energy demand and reduce dependence on fossil fuels. China’s emissions under current policies are projected to plateau at a high level until 2030 and emissions in 2030 have been raised by 2-5% from the previous assessment, adding extra burden on reaching long-term carbon neutrality. Under current policies meaning the country is expected to grossly overachieve its energy-related NDC targets but is in danger of missing its carbon intensity target for the first time. The CAT gives China’s climate policies a rating of “Insufficient”.

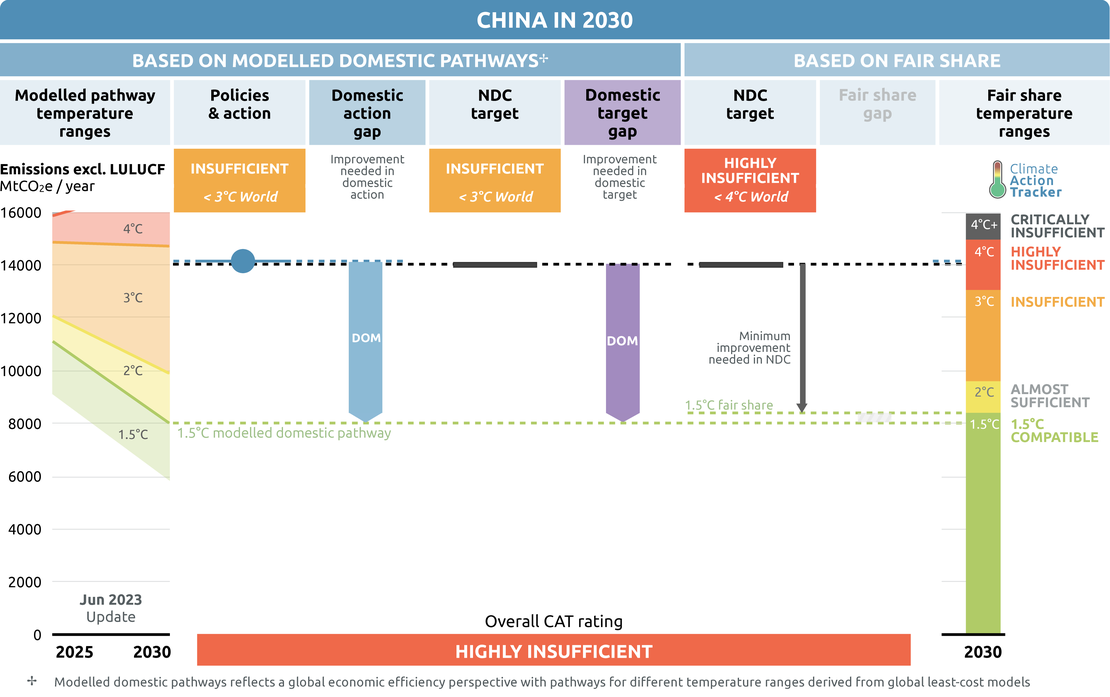

After revising our projections to incorporate the latest policy developments and analysis, we project GHG emissions levels of 14.2 GtCO2e in 2030.

The CAT rates China’s policies and action as “Insufficient” as current policy projections closely match China’s modelled domestic pathways consistent with global warming of over 2°C and up to 3°C by the end of the century (if all countries had this level of ambition). The “Insufficient” rating indicates that China’s climate policies and action in 2030 need substantial improvements to be consistent with the 1.5°C temperature limit. China is expected to implement additional policies with its own resources but will also need international support to implement policies in line with full decarbonisation.

Further information on how the CAT rates countries (against modelled domestic pathways and fair share) can be found here.

Policy overview

China’s policy projections have been updated to reach GHG emission levels (excl. LULUCF) of 14.2 GtCO2e/yr in 2030, representing an increase in total GHG emissions of roughly four times higher than 1990 levels. The projections suggest China is likely to comfortably achieve its energy-related NDC targets but, for the first time, is in danger of just missing one NDC target (carbon-intensity.)

China's energy consumption and dependence on fossil fuels is the most important single factor driving global emissions. While the country aims to phase down from coal starting 2025, it continues to support the fossil fuel in its medium-term energy strategies to maintain security despite a continued concerted effort in the buildout of renewable energy sources. China increased coal production by 10.5% in 2022 to record levels and still has over 125 GW of coal-fired power plants in the pipeline despite the envisaged phase-down, although the consumption outlook on coal remains uncertain (Global Energy Monitor et al., 2023; National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2023). China is preparing for its post-coal transition by turning to natural gas and renewables; the country has become the largest liquified natural gas (LNG) importer and holder of the most long-term purchase agreements globally while at the same time the government is developing renewable energy sources at record pace (Stapczynski, 2023). Although gas consumption is not envisaged to peak in the next decade, China is relying heavily on non-fossil sources (renewables and nuclear) for its long-term energy supply.

By 2030, China’s NDC targets aim to have non-fossil fuels make up around 25% of primary energy consumption and increase wind and solar power capacity to 1,200 GW (MEE of China, 2022). By 2025, China’s 14th Five Year Plans (FYP) for energy and renewables aims to have a 20% non-fossil share in primary energy consumption and a 39% share in generation, with renewables making up half of the country’s installed capacity and half of incremental growth in power demand (NDRC, 2022).

Renewable capacity installations in China have been growing exponentially, with capacity growing more than 350% since 2010. China is expected to exceed 1,500 GW of combined non-fossil capacity by 2025 and 2,500 GW in 2030. Despite this, our assessment shows that China’s development is not large or fast enough to displace fossil fuels in a substantial way, even with impressive growth from wind and solar. Hydropower has and is expected to continue providing the majority of renewable power before 2030, which is an energy security risk that could lead to backsliding onto fossil fuels (Bradsher and Dong, 2022).

China launched its Emissions Trading Scheme in 2021 (after a decade of pilot projects) to bring down the emissions-intensity of coal plants and encourage earlier retirement for a young coal-fired power plant fleet. The ETS covers over 2,000 companies in the power sector (coal and gas plants), 10% of global carbon emissions, and recorded over 10 billion yuan (USD 1.4bn) in total transactions by the end of 2022. However, the scheme has been inhibited by challenges in power market interactions, data quality and ETS design, limiting the ability of carbon prices to drive sector decarbonisation (Qin et al., 2022). The ETS is planned to expand to seven other sectors in the future, with high-emitting industry subsectors such as iron and steel, cement, and aluminium the most likely to be included (Tan, 2022).

China's industry sector is targeting electrification and efficiency improvements to meet demand and reduce reliance on fossil fuels. Steel, cement production, and aluminium are the main drivers of emissions in the industry sector; all the subsectors have aligned with the economy-wide carbon peaking timeline before 2030 (MIIT of China, NDRC and MEE, 2022). However, public researchers and industry associations have previously indicated in drafts or consultations that an earlier peaking timeline is feasible (e.g., China Dialogue, 2022).

The development of carbon capture, utilisation, and storage (CCUS) and hydrogen solutions have also become a priority area for research to decarbonise hard-to-abate sectors. China, the world's largest producer of hydrogen, published its national hydrogen strategy and is targeting modest production of 100,000–200,000 tonnes of renewable-based hydrogen by 2025, which could reach 100 million tonnes by 2060 (Yao, 2022).

China's transport sector consumes almost 50% of oil consumption nationally when consumption of the fuel is due to peak before 2030. To transition to a low-carbon sector, the government has spent decades prioritising new energy vehicles (NEVs) sales, including battery electric vehicles (BEVs), plug-in hybrid vehicles (PHEVs), and fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs). Despite ending NEV subsidies for producers in 2022, the NEV market share reportedly exceeded 25% in 2022 (already exceeding a 20% target in 2025); the government aims for a 40% market share by 2030 (Government of China, 2021; Pontes, 2023).

China has also been prioritising improving accessibility and electrification of its public transport systems, with the expansion of national high-speed rail and local electric public transport systems prominent in its COVID economic stimulus packages and latest FYPs. The government aims to extend its massive high-speed rail network by another 120,000 km by 2035 and have it cover more than 95% of cities with a population greater than half a million by 2025 and has launched a pilot program for cities to procure around two million electric public vehicles before 2035 (Wang, 2022; CGTN, 2023).

China’s continuing urbanisation trend is expected to result in a large increase in energy consumption and emissions from the construction sector. To address this, the Chinese government has outlined targets in its 14th Five-Year Plan (FYP) for Building Energy Efficiency and Green Building and Implementation Plan for Carbon Peaking in Urban and Rural Construction (MoHURD of China, 2022; MoHURD of China and NDRC, 2022).

The plan sets energy consumption caps in building operations, increases the energy efficiency of new buildings, and sets indicators for renovating existing buildings with efficiency measures and constructing ultra-low or zero-energy consumption buildings. The plans also contain indicators for increasing solar and geothermal applications to new buildings, raising the proportion of energy from renewable electricity, and reducing emissions-intensity and energy intensity in residential and commercial buildings.

China has increased efforts to expand its forestry and grasslands, in part due to their role in achieving the country’s carbon peaking and carbon neutrality targets. The government has implemented various domestic forest conservation and afforestation policies, and in the 14th FYP, it has set a target to plant 36,000 km2 of new forest annually until 2025 to increase the country’s forest coverage (NGFA of China, 2021).

However, estimates of China’s forest carbon sequestration potential contain uncertainties, and using sinks from the forestry sector cannot be used as an excuse to delay emission reductions in other sectors. Internationally, China has increased its forestry pledge and signed the Glasgow Declaration on Forest and Land Use, and separate joint agreements with the EU and the US on reducing deforestation. China chaired the UN Biodiversity Conference in Montreal in 2022, resulting in the adoption of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which contained 23 separate targets to achieve by 2030.

Sectoral pledges

In Glasgow, a number of sectoral initiatives were launched to accelerate climate action. At most, these initiatives may close the 2030 emissions gap by around 9% - or 2.2 GtCO2e, though assessing what is new and what is already covered by existing NDC targets is challenging.

For methane, signatories agreed to cut emissions in all sectors by 30% globally over the next decade. The coal exit initiative seeks to transition away from unabated coal power by the 2030s or 2040s and to cease building new coal plants. Signatories of the 100% Evs declaration agreed that 100% of new car and van sales in 2040 should be electric vehicles, 2035 for leading markets. On forests, leaders agreed “to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030”. The Beyond Oil & Gas Alliance (BOGA) seeks to facilitate a managed phase out of oil and gas production.

NDCs should be updated to include these sectoral initiatives, if they're not already covered by existing NDC targets. As with all targets, implementation of the necessary policies and measures is critical to ensuring that these sectoral objectives are actually achieved.

| CHINA | Signed? | Included in NDC? | Taking action to achieve? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methane | No | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Coal exit | No | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Electric vehicles | No | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Forestry | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

| Beyond oil and gas | No | No | No |

- Methane pledge: China did not adopt the methane pledge. Methane is a significant source of GHGs emissions in the country—surpassing 1.4 GtCO2e/year since 2020 according to our estimates—split between the energy (~47%), agriculture (~39%) and waste (~14%) sectors.

China’s updated NDC does not have explicit reduction targets for non-CO2 gases, though Measure 13 outlines their goal to accelerate control of these gases and phase out HFC gases under the Kigali Amendment.

The methane pledge unveiled at COP26 was received cautiously from China, with national experts citing different national circumstances and political gaming as potential reasons for not joining. However, China has continued its intention to tackle methane emissions, as evidenced both by its 14th FYP outline and the “U.S.-China Joint Glasgow Declaration on Enhancing Climate Action” during COP26, where the two largest global emitters stated their intent to cooperate to control and reduce methane emissions and China stated its intent to “develop a comprehensive and ambitious National Action Plan on methane, aiming to achieve a significant effect on methane emissions control and reductions in the 2020s”. If China were to sign up to and implement the pledge, we calculate that it would reduce methane emissions by 420 MtCO2e/year in 2030.

- Coal exit: China has not adopted the coal exit, though it is the largest consumer of the fossil fuel. The country is committed to decrease its reliance on coal (and fossil fuels in general) in its NDC and has signalled a peaking of coal consumption by 2025. However, China has the world’s largest coal-fired power plant pipeline by far, with over 126 GW of domestic coal-fired power plants in the pipeline in 2023 (Global Energy Monitor et al., 2023).

Although the peak of China’s coal capacity and consumption is uncertain in its NDC and other high-level medium-term policies, building (and utilising) additional coal capacity will make it more difficult to achieve its NDC’s non-fossil energy targets and long-term carbon neutrality targets. For more detail on coal developments, see the section on Energy Supply below.

- 100% Evs: China did not adopt the EV target during COP26. Decarbonising transport is not explicitly part of China’s NDC commitments, although the country is prioritising the transition towards electrified transport. China has targets of 20% new energy vehicle sales by 2025 and 40% by 2030 (Government of China, 2021).

- Forestry: China signed the forestry pledge at COP26 on November 2, 2021, committing to end deforestation by 2030. While such a commitment is not part of China’s NDC, the document contains a target to increase the forest stock volume by 6 billion cubic meters from the 2005 level. For more details on China’s forestry policy developments, see the Forestry section below.

- Beyond oil & gas: China has not signed up to the alliance, and has no clear intention of phasing out oil and fossil gas production. China has shown intention in its 14th FYP to peak and plateau oil consumption before 2030, while gas will become an increasingly important fuel for China as it seeks to prioritise reducing coal consumption in the medium term.

Energy Supply

China’s immense energy consumption (where coal, oil, and gas supply 56%) is the largest contributor to global emissions (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2023). Fossil fuel dependence is continuing to serve as the foundation of the energy system and primary backup for energy security, as the build-up of coal reaches its highest levels and expansion of capacity runs opposite to global trends. Non-fossil energy sources, particularly wind and solar (but also hydro and nuclear), are all ramping up in the medium term and remain the primary objective for the energy system to prepare China for the post-coal era. Chinese energy policy continues to drive the growth of both clean and polluting sources as energy demand is expected rise again in 2023 (and beyond): emissions in the short-term will depend on extreme weather events and whether non-fossil fuel sources can keep up with energy demand.

Controlling coal and fossil-fuel consumption

Despite China’s intention to wean off coal dependence in the long-term by “strictly control coal consumption” before 2025 and to “phase down coal consumption” over the 15th FYP (2026–2030), its short-term stance has moved heavily toward supporting fossil fuels, and particularly coal after the country’s power shortage in 2021. Recently, the government’s Work Report 2023 from the Two Sessions, China’s annual meeting of the top legislature and national political advisory bodies allre-emphasised coal’s importance to energy security and applauded the fuel’s role in the country avoiding a major energy crisis during the winter (State Council of China, 2023). The National Energy Administration’s “Blue Book on New Power System Development” (in consultation) still reinforces coal as the foundation of energy security (NEA, 2023a).

China has been responding to the top-level guidance by increasing coal production in 2022 by a staggering 10.5% to 4.6 billion tonnes, after a year that already produced a record high coal output (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2023). The NEA’s 2023 work plan calls for a further 2% increase in coal output and an acceleration of coal mine approvals when coal mine capacity utilization was at its highest levels in seven years in 2022 (NEA, 2023b; SxCoal, 2023).

The government still has plans to build 126 GW of coal plants according to Global Energy Monitor (and the China Electricity Council (CEC)forecasts even more) – while yet again, the global coal fleet (in developed or developing countries) shrank excluding China (CEC, 2021; Global Energy Monitor et al., 2023). This build-up is despite coal plants becoming more expensive to operate as cheaper renewables are added to the grid; coal electricity costs in China are expected to more than double by 2050 as utilisation hours decline drastically after 2030.

While “in principle” the country no longer builds any more coal-fired power projects (whose sole purpose is to generate electricity), planners continue to build coal-fired power plants under two exceptions: to provide energy security and to support flexible peaking services under further development of renewable energy (China Energy News, 2022).

Coal consumption also grew (to a lesser extent than production) by 4%, in line with electricity (+3.6%) and energy consumption (+2.9%) growth, despite a year where industrial power consumption roughly stayed stable (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2023). Expectations of a rebound in 2023, along with forecasts of heat waves and drought (which increases demand and reduces availability of hydro generation), mean that power sector emissions will likely rise in 2023. We project the share of coal to drop to 49% by 2025 when consumption peaks, and to decline further to 41% by 2030.

However, as China eventually decreases its dependence on coal power and oil—the latter is to peak and plateau before 2030—it is likely to compensate this with an increased consumption of natural gas in addition to clean energy sources, given the country’s energy demand is also rising.

Before Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine, China and Russia agreed long-term significant oil and gas contracts (for up to 30 years) to increase imports into China (Chen, 2022). China already overtook Japan to become the world’s largest liquified-natural-gas importer in 2021 and is building 90 GW of new gas plants to satisfy heating and power needs in the future.

Energy companies in China have shifted its strategy towards securing more long-term contracts due to high and volatile spot prices and increasing demand, and hold the most LNG purchase agreements of any country (Corbeau and Yan, 2022; Stapczynski, 2023). China has existing plans to extend its gas pipeline infrastructure by 40%, which would double its LNG import capacity. These developments could potentially lead to stranded assets in the order of an estimated USD 89bn (Rozansky and Shearer, 2021; Aitken et al., 2022; Caixin, 2022) .

To be compatible with a 1.5°C pathway, China would need to decrease the share of unabated coal in power generation to at least 35% in 2030, with a complete phase-out before 2040 (Climate Action Tracker, 2021a). China’s coal share of power generation was 64% in 2020 (see graph below) and could still reach levels of around 47% in 2030 and 30% in 2040 according to our current policy projections.

Renewable and non-fossil energy growth

Renewables are playing a larger and more obvious role in national energy security, despite the continuing strong focus of fossil fuels. In its NDC, China’s non-fossil and renewable energy targets are to increase the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption to “around 25%” in 2030 and increase the installed capacity of wind and solar power to 1,200 GW by 2030 (MEE of China, 2022).

According to the 14th FYPs on energy and renewables, China should reach a 20% non-fossil share in consumption and a 39% share in generation (33% from renewables; 18% excluding hydro) by 2025 (NDRC, 2022; NDRC and NEA, 2022). Renewables should also make up half of the country’s total installed capacity by 2025, expected to reach roughly 3000 GW, as well as half of incremental growth in power demand (SASAC, 2021). Electrification of China’s end-use sectors is also a strategic priority for the country, with the government targeting a 30% share of electricity in final energy consumption in 2025, marking an increasing importance of renewables in bringing down emissions.

China’s renewable energy capacity installations continues to grow in parallel with fossil fuels. Renewable capacity reached more than 1,160 GW in 2022, showing an exponential trajectory from the approximately 250 GW installed by 2010 and 500 GW installed by 2015 (National Bureau of Statistics, 2022; CEC, 2023). Wind and solar capacity were at 365 GW and 390 GW, with hydropower still representing the largest single source of renewable capacity at 410 GW. The CEC forecasts an additional 180 GW in non-fossil capacity to be added over the course of 2023, with the share of non-fossil capacity reaching over 50%, putting China on a strong course to achieve the RE capacity share target (nuclear is only a minor share).

We expect combined non-fossil capacity to exceed 1,500 GW in 2025 with wind and solar exceeding 1,000 GW alone. A study conducted by the Chinese Research Academy of Environmental Sciences and the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs on provincial plans suggest that China could achieve its NDC target for 1,200 GW of solar and wind already five years early by 2025 (Liqiang, 2023).

According to the Energy Research Institute, an affiliate of the National Development and Reform Commission, China’s pathway to achieve its 2060 carbon neutrality target would result in 1,650 GW of wind and solar in 2030 while our CAT assessment projects even more (ERI, 2021). To reach this level China would have to build around 110 GW of wind and solar annually to 2030, which it is on track for so far (the NEA expects 160 GW installed in 2023 and announced China already built 48 GW of solar in the first quarter) . The Ministry of Ecology and Environment expects half of China’s energy consumption in 2045 to be satisfied with RE, with the figure rising to 68% in 2060 (nuclear expected to rise to 13%).

To be compatible with a 1.5°C pathway, China would need to have shares of renewable electricity generation reach at least 75% in 2030:; we expect China to reach 45% by that time. Globally, all countries will need to have 98–100% renewable electricity shares by 2050 to be 1.5°C-compatible (Climate Action Tracker, 2020b)

Industry

Industry is the largest energy consuming sector in China, accounting for about 58% of the country’s final consumption in 2021. Half of the direct energy consumed in the sector currently comes from unabated coal and gas although combined shares of the fossil fuels are expected to plateau in the next decade as China targets increasing electrification and efficiency to meet expected demand (IEA, 2022b). Steel and cement output for real estate and infrastructure construction are the main drivers of industry emissions and the primary cause of China’s dip in emissions in 2022.

China’s crude steel output dropped by 2% to just over 1 billion tonnes in 2022, continuing the decreasing trend for the third year running (Bloomberg News, 2023; National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2023). While domestic steel demand is expected to peak in the coming years, the global appetite for steel (for which China is a major supplier) is likely to increase in developing regions such as ASEAN, Africa, and India (IEA, 2021b).

Given the sector’s gargantuan energy consumption, decarbonisation of major industrial subsectors is critical—and central—to achieving national climate and energy targets. The government’s new industry peaking implementation plan has aligned the entire sector’s CO2 emissions peaking timeline with China’s 2030 NDC target, while the 14th FYP for Green Industry Development has matched the economy-wide energy and emission intensity reduction targets (MIIT of China, 2021; MIIT of China, NDRC and MEE, 2022).

Key emitting sectors, such as cement, steel, and aluminium are likely to be the first targeted in the scope expansion of the country’s ETS (Wang, 2021; Wulandari, 2022). However, reports suggest that the expansion could be delayed until 2023 or 2024 due to poor data quality of emissions accounting and bureaucratic constraints (Bloomberg News, 2022; Peiyu and Hui, 2022).

The cement sector is targeted to peak before 2030 and reduce the energy intensity of production by 3% by 2025 (from 2020 levels) (MoHURD of China and NDRC, 2022). The sector has discussed pushing forward the emissions peak to as early as 2023, which is in line with calls from the China Building Materials Federation, independent estimates from groups including public institutions, and reports from state-owned media (Murtagh, 2022; Schmidt, 2022). Cement production remarkedly dropped more than 10% in 2022, triggering a decline worldwide (China accounts for more than half of global production) (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2023).

The iron and steel sector has also delayed its emission peaking timeline also to 2030 after initially consulting on an emissions peak in 2025 with aims to reduce its carbon emissions by 30% from the peak by 2030 (China Dialogue, 2022; MIIT of China, 2022). The five-year delay in steel sector peaking could be to allow the sector breathing room amidst energy and supply chain security concerns, and to consolidate a less ambitious target that could be reached by all steel companies (rather than as a sector) in a bid to tackle other industry concerns such as overcapacity and pollution (Guoping and Zou, 2022; Lin, 2022). By 2025, the sector will also reduce the energy intensity of producing steel by 2% and reuse 320 million tonnes of scrap steel in efforts to improve efficiency and build towards a circular economy (NDRC, 2021a).

Similarly, China’s aluminium sector is targeting a peak in carbon emissions by 2030 (with 30% of the energy inputs to electrolytic aluminium production from renewables) after considering a 2025 target (analysts claim this may even be sooner) (Bloomberg, 2021; EEO, 2021).

To fully decarbonise China’s hard-to-abate sectors, development of CCS/CCUS and hydrogen solutions have become priority strategy areas for Chinese industry. CCUS will be a critical technology to help China drastically reduce emissions towards carbon neutrality in the long-term and has received increasing national attention in the last two decades, with objectives now focusing mainly on large-scale project demonstrations.

As of 2021, CCUS was highlighted in the last three FYPs, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) have encouraged provinces to pilot and demonstrate CCUS projects, and 29 provinces had already issued policies and plans related to the technology. Since the 10th FYP (2000–2005), China has invested more than 3bn yuan into CCUS R&D (Fan, 2021).

China, the world’s largest producer of hydrogen, published its national hydrogen strategy (2021–2035) in 2022, confirming the technology’s key role in China’s future energy system and mitigation efforts. While hydrogen is mainly produced from coal and gas sources, the plan targets a modest production of 100,000–200,000 tonnes of renewable-based hydrogen with renewable sources by 2025 (Yao, 2022). Given China’s hydrogen production reached 25 million tonnes in 2022, this would constitute less than 1% of its production. The China Hydrogen Alliance estimates this could reach 100 Mt by 2060, accounting for 20 percent of the country’s final energy consumption (Nakano, 2022).

China has further been active in tackling non-CO2 emissions, most notably in regulating hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) emissions from refrigeration and cooling activities embedded in many industrial activities. China produces – and consumes – more than 60% of the world’s HFCs. China’s first NDC committed to targeted reductions of HCFC22 production of 35% by 2020 and 67.5% by 2025 below 2010 levels, but there are no numerical targets in its updated NDC.

In US-China bilateral climate discussions in 2021, both countries recommitted to implement the phasedown of HFC production and consumption, reflected in the Kigali Amendment, a commitment also re-emphasised in a bilateral agreement between French President Macron and President Xi in 2019 (IGSD, 2019; US DOS, 2021).

China finally ratified and started enforcing the Kigali Amendment in 2022 (Rudd, 2021). China reported that it halted new production capacity of five of the 11 HFCs it produces (covering 75% of total HFC production) two years ahead of the freeze requirements of the Amendment (McKenna, 2022). According to our analysis, under the Kigali Amendment’s phase out schedule, China would reduce emissions by a modest ~40 MtCO2e/year by 2030, although emission reductions could increase to almost 400 MtCO2e/year by 2045. A 2019 estimate that a full phase-out of all HFC gases could reduce China’s emissions by more than 650 MtCO2e/yr in 2050 below current policies at the time (Lin et al., 2019).

Transport

China’s transport sector is a vast consumer of energy (trailing only the industry sector), with urban passenger transport activity having increased ten-fold since 2005 (Energy Foundation China, 2020). The sector accounts for 14% of final energy consumption and almost 50% of oil consumption nationally, with petrol cars the largest consumer and source of emissions (IEA, 2022b).

The government has signaled its continuing intent to accelerate the transition towards a low-carbon fleet, with sector action critical to meeting economy-wide targets of 30% share of electricity in final energy consumption in 2025 and peak oil consumption during the 15th FYP period (2026 to 2030) (Government of China, 2021; NDRC and NEA, 2022).

China’s uptake of new energy vehicle (NEV), including battery electric vehicles (BEVs), plug-in hybrid vehicles (PHEVs), and fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs), started in the 1990s. The growth in NEV sales has been rapidly increasing due to subsidies dating back to 2009 and more recently, investment boosts from pandemic recovery packages and strong national policy signals.

However, the government has been aiming to decouple the growth of NEVs with direct financial incentives due to accelerating market forces and the growing government costs of the subsidies. NEV subsidies for producers ended in 2022 (originally planned for 2021 but extended during the COVID pandemic) although tax exemptions for consumers will continue until the end of 2023. Research suggests the market is reaching maturity, with BEVs achieving price parity with conventional cars in the near future, even without accounting for fuel savings (Lutsey et al., 2021).

The NEV Industry Development Plan (2021-2035) targeted NEV sales to take 20% of the market share by 2025, but reports suggest market share already exceeded 25% in 2022 (BEVs alone reached over 20%) and will rise significantly in 2023 (Office of the State Council China, 2020; Fu Sheng, 2023; Pontes, 2023). China further targets a NEV market share target of 40% by 2030 (raised to 50% in select regions with high air pollution) (Government of China, 2021).

Our previous analysis on NEV penetration in China shows limited domestic mitigation impact as even a policy target of 100% BEV sales by 2035 would mean negligible emission reductions by 2030, and from 370 to 850 MtCO2e/year in 2050 depending on the emissions-intensity of the power sector (Climate Action Tracker, 2021b).

Despite this, China’s rapid development of industrial infrastructure and its EV supply chain is critical to other countries’ electric mobility transitions and pursuit of zero emissions: in 2022, China shipped the 35% of the world’s exported electric cars, produced over 70% of lithium-ion batteries and other battery components, and was home to over half of the processing and refining capacity for lithium, cobalt and graphite (IEA, 2022a, 2023b).

To limit global temperature increase to 1.5°C, China will need to sell the last fossil fuel car by 2040 meaning a NEV market share of 100% (Climate Action Tracker, 2020a). Projections (from 2021) show China only reaching 70% by then, although this is the most rapid trajectory of the world’s largest emitters.

The government has also been prioritising service and electrification of its public transport systems with expansion of national high-speed rail and local electric public transport systems highly prominent in its COVID economic stimulus packages and latest FYPs. The 14th FYP for Green Transportation Development contains numerical targets to increase the growth of NEVs in urban public transport (including taxis, buses, delivery trucks, and more), while the government recently launched a pilot programme for cities to procure 80% of new public vehicles as electric from 2023-2035 (around two million vehicles) (MoT of China, 2021; Xue, 2023). Shenzhen, a city home to two pilot programmes for NEVs since 2009, became the first city in the world with an entirely electric public transport system in 2017 (including 16,000 buses and 20,000 taxis) (CGTN, 2023).

For intercity transport, the government has looked to expanding its massive high-speed rail network. The network consisted of about 38,000 km in 2020 (all built since 2008) and is planning to extend this by another 120,000 km by 2035 (Jones, 2022; Wang, 2022). By 2025, the government aims to have the network cover more than 95% of cities with a population greater than half a million (State Council of China, 2022).

Buildings

China’s buildings accounted for about 22% of the country’s final energy consumption in 2021, with almost 40% of the energy consumed coming from electricity (IEA, 2022b).

China constructs the most buildings globally, having on average constructed around four billion m2 of new floor space annually over the last decade (despite a slowdown since 2020) (National Bureau of Statistics, 2021). China’s continuing urbanisation trend is expected to come with a large increase in energy consumption and embodied emissions from the construction sector: the efficiency with which new floor space is built will impact China’s ability to meet headline energy intensity reduction goals in the economy (-13.5% from 2021 to 2025), while the production processes for carbon-intensive construction materials, such as steel and cement, is vital to China’s carbon peaking goals.

The 14th FYP for Building Energy Efficiency and Green Building and Implementation Plan for Carbon Peaking in Urban and Rural Construction outlines the government’s main targets for 2025, including setting energy consumption caps in building operations and increasing energy efficiency of new public and residential buildings by 20% and 30% (MoHURD of China, 2022; MoHURD of China and NDRC, 2022).

The document further sets indicators for renovating 350 million m2 of existing buildings with efficiency measures and constructing 50 million m2 of ultra-low or zero-energy consumption buildings. Retrofits of buildings are paramount in China’s bid for energy efficiency in the sector, as the average age of buildings stock is young at 15 years, meaning almost half of existing floor space could still exist by 2050 (IEA, 2021a).

China launched its Near Zero-emission Buildings Standard (NZEB) in 2019 to provide an appendage to the “Green Building Evaluation Standard” and the ongoing development of green buildings, defined as buildings that save energy, land, water, materials and are ecologically unharmful (MoHURD of China, 2019; Cao et al., 2022). More than 2.5 billion m2 of urban and commercial floor space has already been green-building certified since 2018, whereas almost 10 million m2 of NZEB projects have either been in construction or completed by 2020 (Zhang and Fu, 2021; Zhang et al., 2021).

The 14th FYP and implementation plan also contain indicators for increasing solar and geothermal applications to new buildings by 2025, aims to have over half of the energy consumed in urban buildings from electricity (fossil fuel sources supplied a third of energy consumption in buildings and half of all space heating in 2021), and raises the proportion of energy from renewable electricity to 8% (from 6% in the 13th FYP) (IEA, 2021a).

For compatibility with the Paris Agreement temperature goals, China’s emissions-intensity in residential and commercial buildings needs to be reduced by at least 65% in 2030, 90% in 2040, and 95–100% in 2050 below 2015 levels, while energy intensity needs to be reduced by at least 20% in 2030, 35–40% in 2040, and 45–50% in 2050 compared to 2015 levels. China will also need to achieve renovation rates of 2.5% per year until 2030 and 3.5% until 2040 to achieve a Paris-compatible buildings sector by 2050 (Climate Action Tracker, 2020b).

Forestry

China’s government and the National Forestry and Grassland Administration (NFGA) has increased efforts on expanding the country’s forestry and grasslands, in part due to its slated role (as carbon sinks) in achieving China’s carbon peaking in 2030 and carbon neutrality in 2060 targets. China’s LULUCF sector, including forestry, represented a carbon sink of approximately 1.1 GtCO2e/year according to the latest national inventory for 2014 (Government of China, 2018).

The government has implemented many domestic forest conservation and afforestation policies, guided by the National Forest Management Plan (2016-2050), with varying degrees of success (e.g., Bloomberg, 2020). Recently, the government has issued plans to plant 36,000 km2 of new forest annually to 2025 in a bid to increase the country’s forest coverage to 24.1% as part of its overall 14th FYP goals (Stanway, 2021). This target is increased from 23% in the 13th FYP, which was achieved in 2020 (SCIO of China, 2020). In the 14th FYP for Protection and Development of Forestry and Grassland (2021-2025), the NFGA detail additional specific protection, restoration and afforestation goals in several priority ecological zones (Tibetan Plateau, Yellow River, Yangtze River, Northeast forest zone, Northeast desertification zone, Southern hilly zone) (NGFA of China, 2021).

To reach China’s carbon neutrality goal by 2060, carbon sequestration through afforestation or other means such as direct air capture, are assumed to play a critical role (He et al., 2021). However, assessments of the carbon sequestration potential of China’s forests contain uncertainties in science and accounting, leading to diverging estimations (e.g., Qiu et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2022). Thus, for Paris Agreement compatibility, sinks from the forestry sector cannot be used as an excuse to delay emissions reductions in other sectors (Climate Action Tracker, 2016).

In international fora, China updated its NDC forestry pledge to increase forest stock volume by six billion m3 by 2030 compared to 2005 levels (up from 4.5 billion m3). In 2021, China signed the Glasgow Declaration on Forest and Land Use (which commits to “halt and reverse” forest loss and land degradation by 2030) at COP26 and issued separate joint agreements with both the EU and the US on enhancing cooperation on reducing deforestation around the same period (DG for Climate Action, 2021; U.S. Department of State, 2021).

The government appears serious in respecting those objectives with action. In 2020, China revised its Forest Law for the first time in 20 years, with the most significant policy change being the implementation of a ban (in effect as of July 2020) on Chinese companies purchasing, processing, or transporting illegal logs (Client Earth, 2020; Mukpo, 2020). As China is the world’s largest importer of legal and illegal logs, with a large portion of its tropical timber imports (in 2018) coming from countries with weak governance, the revised law could have a large impact on curbing global deforestation (Global Witness, 2019; Interpol, 2019).

China chaired the UN Biodiversity Conference in Montreal in December 2022 (originally to be hosted in Kunming but rescheduled after years of delay due to COVID) which resulted in the adoption of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. The landmark agreement contains 23 targets to achieve by 2030, including covering 30% of Earth’s land, coastal areas, and ocean under protected areas (UNEP, 2022).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter