Country summary

Assessment

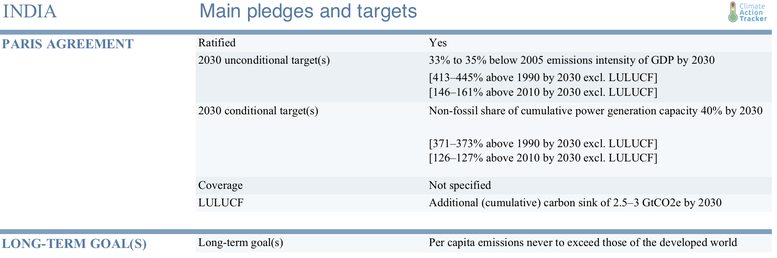

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought significant social and economic challenges on top of a series of climate disasters such as Cyclone Amphan. The economic standstill due to the pandemic is leading to sharp reductions in emissions in the short term, but they will start increasing again at the same rate unless India develops a focused green COVID-19 recovery strategy. With a large stimulus package of 10% of GDP announced, and the experience of clean air during lockdown, the crisis presents an opportunity for India to accelerate a transition away from coal to renewable energy as well as accelerate an uptake of electric mobility. There are no clear signs that India is seizing this opportunity. While no new coal power stations have been built in 2020, the government is encouraging more coal mining and increased coal production which is not consistent with a green recovery. India needs to develop a just transition strategy to phase out coal for power generation before 2040. The CAT rates India’s NDC target as “2°C compatible” indicating that India’s climate commitment in 2030 is considered to be a fair share of global effort based on its responsibility and capability. But it is not consistent with the Paris Agreement, and domestic emissions need to peak and start reducing, including with international support. There is potential for the nation to become a world leader with enhanced 1.5 compatible targets and a just and swift transition away from coal and accelerate the transition to renewable energy. which would bring large benefits for sustainable development including health and employment.

We expect that GHG emissions in 2020 will be 6% to 10% lower than 2019. Given India has pledged a GDP intensity target for 2020, the emissions level of the target is reduced compared to the estimate before the pandemic (by 9-12%). The COVID-19 pandemic has brought India’s economy to a standstill, with demand for fuels and electricity falling sharply, although some parts of the economy have started recovering.

Coal-fired generation and its share in the power mix fell sharply in the first half of 2020 – by 14% compared to H1-2019, and the share of renewable energy increased. Energy related CO2 emissions growth was already slowing down in 2019 due to reduced electricity demand and increased share of renewable energy.

COVID-19 has multiplied the vulnerability of people who are at risk of displacement by storms, floods and other climate disasters. The Indian government responded to the economic crisis with one of the largest stimulus packages in the world as share of GDP. While there is no explicit green recovery programme, there are discussions about using part of the stimulus package to support development of the renewable energy industry and manufacturing of electric vehicles.

The government is urging states to provide incentives for setting up designated manufacturing hubs for renewable energy in India and is providing support for renewable energy. The recent experience of cleaner air due to the drastic drop in pollution levels have started discussions around strengthening ambient air quality standards. There are calls for a green recovery focusing on opportunities in power, transport, and urban planning including to strengthen ambient air quality standards.

The Modi Administration continues to provide mixed and inconsistent policy signals in relation to India’s energy transition, with a push towards higher shares of renewable energy including new policies for renewables in rural areas and for electric mobility, as well as a push toward increasing domestic manufacturing and production, but no clear pathway for a transition away from coal of fossil fuel based mobility.

While no new coal-fired power station has been built in the first half of 2020, India keeps planning for more coal capacity, despite utilisation rates of coal power plants falling and their profitability already at risk. Based on current coal expansion plans, capacity would increase from currently more than 200 GW to almost 300 GW over the coming years. Coal production is increasing on track to reach a record level this year. A recent move to increase domestic coal production opening coal mining to private investors risks the destruction of ancient forests and ecological areas.

The CAT’s India emissions projections are 9-12% lower in 2030 compared to our previous projections in December 2019, due to the impact of the pandemic on the economy. Given India has a GDP intensity target, our estimate of the emissions level for the NDC target is 8-11% lower compared to our previous projections in December 2019. India would still overachieve its 2030 targets by a wide margin, including even the more ambitious 40% non-fossil capacity share target. However, with current energy targets and policies, emissions are projected to keep increasing (by 24-25% above 2019 levels in 2030) and show no signs of peaking, in particular due to the lack of a policy to transition away from coal. Such an increase of emissions is not consistent with the Paris Agreement. Instead, domestic emissions need to peak and start reducing, with international support.

The CAT rates India’s existing target under the Paris Agreement “2°C-compatible”, as it is within the range of what is considered to be a “2°C compatible” fair share of global effort, even while it allows the country’s total emissions to increase. India could become a global climate leader with a “1.5˚C compatible” rating if it enhances its NDC target, abandons plans to build new coal-fired power plants, and instead develops a strategy to phase out coal for power generation before 2040. Moving to an absolute target instead of the GDP intensity target would enhance transparency and certainty.

India will meet and overachieve its NDC targets with currently implemented policies. There is room to update and adopt more ambitious targets and accelerate the transition away from coal and towards renewable energy.

Our analysis shows that India can achieve its NDC target with currently implemented policies. We project the share of non-fossil power generation capacity will reach 60–65% in 2030, corresponding to a 40–43% share of electricity generation. India’s emissions intensity (excluding the agriculture sector) in 2020 will be 37-39% below 2005 levels; and 54-55% below 2005 levels by 2030. Thus, under current policies, India is likely to achieve both its 40% non-fossil target and its emissions intensity target.

India has a target of 175 GW of renewable energy capacity by 2022 and 450 GW by 2030, including an expansion of solar investments into the agricultural sector, harnessing the potential of off-grid solar PV pumps to not only provide reliable electricity for pump sets, but also to provide additional income generation opportunities for famers (India to Have 450 GW Renewable Energy by 2030: President, 2020). For the first time in 2018, solar investments exceeded investments in coal. The ramp-up of renewables in India can provide access to affordable power at scale, and quickly, with the cost disparity between falling auction prices for wind and solar and increasing cost of coal fired power generation increasing.

A significant caveat on the outlook for India is the ongoing expansion of coal. The Paris agreement 1.5 Celsius limit means that there needs to be a phase-out of coal in the power sector by 2040 in India. The National Electricity Plan (NEP) in 2018 included more than 90 GW of planned coal-fired capacity which would increase emissions unnecessarily, and risk becoming stranded assets. Abandoning these plans is more than feasible when we consider recent developments such as a 50% decrease in the cost of solar power in just two years and several utilities shelving plans to build coal plants.

While India’s coal production is increasing and is on track to produce a record high 700 Mt of coal in 2020/21, its expansion of coal fired power generation has slowed, with no new construction in the first half of 2020.

The increase in energy-related emissions had already slowed down in 2019 before the pandemic hit, due to a weakening economic growth and increase in renewable energy, leading to lower utilisation rates of coal power plants, further impacting their profitability. Expansion plans will increase the risk of stranded assets.

While interventions in the electricity sector have largely been driven by strong policy commitments, there is also increasing action in the transport sector. India has a target of 30% sales of electric vehicles by 2030, down from its originally-proposed 100%, which would have been a Paris Agreement consistent benchmark. Recent policy announcements indicate the government is prioritising charging and manufacturing infrastructure development to facilitate a transition to a low carbon transport system. In July 2020, India railways announced plans to achieve net zero emissions by 2030. This follows a target to achieve complete electrification of its network by 2023.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter