Policies & action

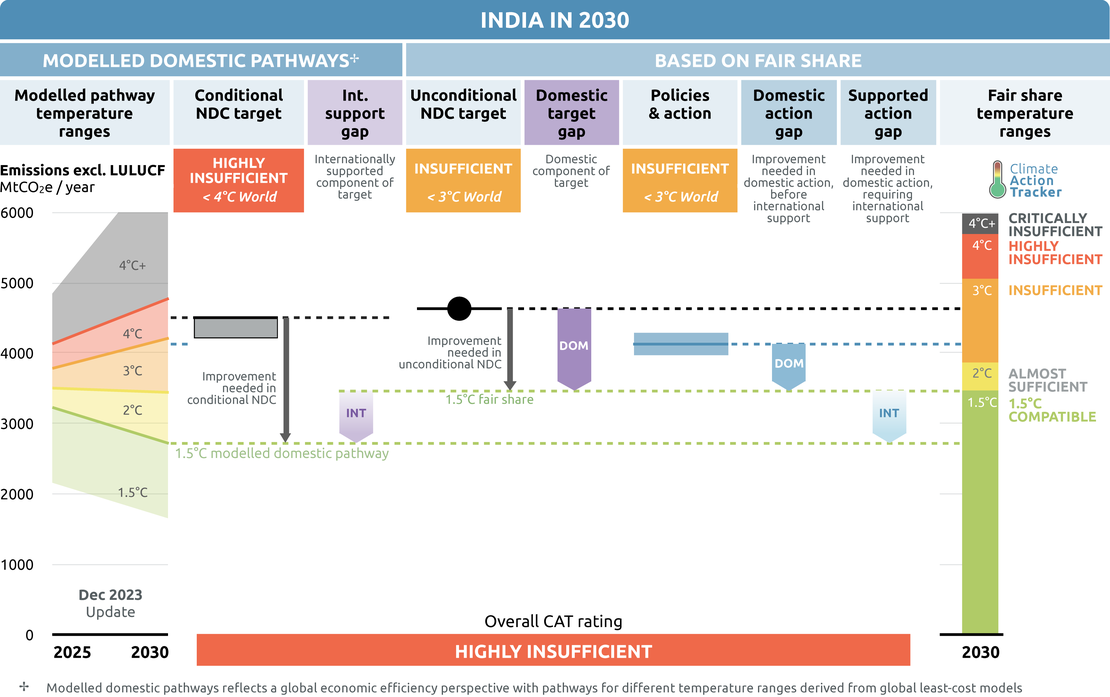

CAT rates India’s current policies and action as “Insufficient” when compared to its fair share contribution. The “Insufficient” rating indicates that India’s climate policies and action in 2030 need substantial improvements to be consistent with the 1.5°C temperature limit. If all countries were to follow India’s approach, warming would reach over 2°C and up to 3°C.

India will need to implement some additional policies with its own resources to make a fair contribution to addressing climate change, but will also need international support to implement all the policies necessary for 1.5°C compatibility.

Further information on how the CAT rates countries (against modelled domestic pathways and fair share) can be found here

Policy overview

The CAT estimates that India’s emissions will be around 4.0-4.3 GtCO2e in 2030 under current policies. This estimate is slightly lower than to our last assessment (July 2023), largely due to a marginal decline in coal-fired power generation along with reduction in other energy-related CO2 emissions from the industry and transport sector.

India’s climate policy is spread across several policy documents, sector-specific strategies and laws with the National Action Plan for Climate Change (NAPCC) serving as the overarching guidance for these efforts. In 2023 some very important policy documents and laws covering the energy sector have emerged, including the National Electricity Plan 2023 (NEP2023), the National Green Hydrogen Mission and the recently amended Energy Conservation Act (Ministry of Law and Justice, 2022; Ministry of New And Renewable Energy, 2023; Ministry of Power, 2022c). These documents and laws play a crucial role in shaping the energy landscape.

India has not yet committed to phasing out coal power or a future without fossil gas. Its latest electricity plan includes an additional 25.5GW of coal capacity for the second half of the decade, on top of the 25.6 GW already under construction (Ministry of Power, 2023b). The government has dropped its plans to add further gas power to its electricity generation, but is still is committed to its vision of creating a gas-based economy more broadly, notwithstanding the energy security risks this creates, given India's dependence on gas imports (Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, 2021; Ministry of Power, 2022c).

The CAT has long-cautioned that fossil gas is not a bridging fuel and the current expansion of LNG in India could put the 1.5°C limit at risk (Climate Action Tracker, 2022a). To align with the 1.5°C goal, fossil gas needs to be phased out from India’s power generation before 2040 (Climate Action Tracker, 2023a).

In 2023 India witnessed an unusually warm summer and, with it, a variable demand for electricity. Despite a 9% overall increase in electricity demand from April to October, the growth was inconsistent.

Initially projected to peak at 230 GW, the summer peak in June reached approximately 220 GW and then declined to 209 GW in July, attributed to a milder summer, especially in northern India (ETEnergyWorld, 2023b). However, demand rebounded, reaching 240 GW in September, surpassing the September 2022 201 GW peak. Power consumption spiked by 16% in August-September 2023 compared to the same period in the previous year (The Hindu, 2023). Below-average monsoon rainfall led to reduced hydro power generation, increasing reliance on coal-fired power, resulting in a record domestic coal production and increase in import.

It is projected that India’s peak demand will reach more than 250 GW in 2024-25 and to meet the evolving demands of the country needs to be more focused in power sector planning with sustainable energy sources (MERCOM, 2023a).

G20 Summit

India hosted the G20 summit in September 2023.

In the G20 communique, world leaders under the Indian presidency committed to tripling renewable energy capacity by 2030 and reconfirmed their commitment to achieving carbon neutrality by 2050 (G20, 2023). While a new renewables target is a positive step, the G20 faced criticism for not setting goals on phasing out fossil fuels (Climate Analytics, 2023).

India, despite positioning itself globally as a green agenda champion, has hesitated to commit to coal phase-out. The nation's argument at COP26 that resisted a coal phase out was also reflected in the G20 declaration, as it continued to stress the "phasedown" of unabated coal, but the term "phasedown" is an incomplete target without specifying the extent and timeframe.

During its G20 presidency, India, by not strongly indicating its commitment to phase out coal, missed an opportunity to push for a global fossil fuel phase-out commitment as leverage for additional financial support and regional backing during COP28 (Davidson, 2023).

Including a timeframe for phasing out fossil fuels could give an important momentum for COP28 and the global stocktake. The G20's climate leadership declaration is inadequate, and highlights the need for substantial commitments at the upcoming COP28 (Climate Analytics, 2023).

Carbon markets

India amended its Energy Conservation Act in December 2022, laying the groundwork for a potential domestic carbon market. The Amendment Act includes provisions for the establishment of a carbon market through the introduction of a 'Carbon Credit Trading Scheme' (CCTS) by the Central Government.

The Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE), in collaboration with the Ministry of Power and the Ministry of Environment, Forest & Climate Change, has been given the responsibility of creating the Indian Carbon Market. The draft framework for the governance structure of the proposed carbon trading scheme is currently undergoing stakeholder consultation (Press Information Bureau, 2023). The pilot carbon market, which will likely include four heavy industries petrochemicals, iron and steel, cement and pulp and paper, is anticipated to become operational from April 2025 (Reuters, 2023h).

Sectoral pledges

In Glasgow, several sectoral initiatives were launched to accelerate climate action. At most, these initiatives may close the 2030 emissions gap by around 9% - or 2.2 GtCO2e, though assessing what is new and what is already covered by existing NDC targets is challenging.

For methane, signatories agreed to cut emissions in all sectors by 30% globally over the next decade. The coal exit initiative seeks to transition away from unabated coal power by the 2030s or 2040s and to cease building new coal plants. Signatories of the 100% EVs declaration agreed that 100% of new car and van sales in 2040 should be electric vehicles, 2035 for leading markets. On forests, leaders agreed “to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030”. The Beyond Oil & Gas Alliance (BOGA) seeks to facilitate a managed phase out of oil and gas production.

NDCs should be updated to include these sectoral initiatives, if they're not already covered by existing NDC targets. As with all targets, implementation of the necessary policies and measures is critical to ensuring that these sectoral objectives are actually achieved.

| INDIA | Signed? | Included in NDC? | Taking action to achieve? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methane | No | N/A | N/A |

| Coal Exit | No | N/A | N/A |

| Electric vehicles | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

| Forestry | No | N/A | N/A |

| Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance | No | N/A | N/A |

- Methane pledge: India is amongst one of the few top methane emitters, along with China and Russia, that has not signed the Global Methane Pledge. Globally, the energy sector needs to lead in methane reductions to 2030 through a phase-out of fossil fuel production in the long-term. India’s plans to expand coal mining are inconsistent with this effort.

- Coal exit: India has not committed to phasing out coal power. Currently, most of its electricity (over 70%) comes from coal. While this share is projected to fall by 2030, it would still be around 50% and total generation would still increase. Its electricity plans envisages building an additional 51 GW of coal power capacity between 2022-2032.

To be 1.5°C compatible, India needs to significantly reduce its coal power generation by 2030 and completely phase-out between 2035-2040. Increasing summer demand for energy is an major opportunity for India to take advantage of the falling cost of solar and accelerate the coal exit. This would also benefit the Indian economy with job creation and improved health. - 100% EVs: India signed the 100% EV declaration, with a focus on two and three-wheeler auto-rickshaws. The government is working on plans to require all two-wheelers to be electric by 2026, much sooner than the COP26 timeline. Two and three-wheelers are the fastest-growing mode of transport in India in terms of sales. Financing will be key to accelerate the e-mobility transition.

- Forestry: India did not sign up to the COP26 forest declaration. It has committed to increasing the size of its land sink by 2.5-3 GtCO2e by creating additional forest cover, a commitment it made as part of its first NDC and one that it did not strengthen as part of its 2022 update. But between 2019 and 2021 forest cover has only increased by 0.2%. Forest area in the country has been increasingly diverted for non-forestry purposes in the last three years, mainly for mining, road construction and irrigation.

- Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance: India is not a member of the Alliance. While it is not a significant producer of oil and gas domestically (in fact, it is highly dependent on imports), it is supporting expansion of oilfields abroad in Russia and Brazil.

Energy supply

Coal

Coal power

India’s electricity generation is heavily reliant on coal power, which represents over 70% of the country’s current generation, with 27 GW of new coal capacity under construction or in advanced planning and an additional 24.2 GW between 2027-2032 (Ministry of Power, 2023b). While India is significantly ramping up its renewable energy, 50% of the country’s power will still come from coal in 2030. This continued reliance on coal is inconsistent with the 1.5°C temperature limit. To be 1.5°C compatible, India's coal power generation would need to reduce significantly by 2030 (i.e. 17-19% of total generation) and be phased out entirely between 2035-2040 (Climate Action Tracker, 2023a). India will need international support to achieve this transition.

While India's intentions for renewable energy for the next decade are clear, when and how it will transition away from coal is not. In the final version of the National Electricity Plan 2023, released in May 2023 (NEP2023), the projected increase in coal capacity grew to 23%, which is higher than the 18% anticipated in the draft version released in September 2022.

India has 27 GW of new coal power plants under construction or at advanced stages of planning (Ministry of Power, 2023b). 25.6 GW of which is expected to come online by 2026 and the reminder by 2032. An additional 24.2 GW of coal capacity has been planned between 2027-2032. The final NEP plan eliminated some of the additional coal capacity envisaged for the period up to FY2026 (7.7 GW), but added substantially more coal for the period up to FY2031 (24.2 GW compared to 9.4 GW). Less coal power would also be retired during this period (4.6 GW under the draft vs 2.1 GW in the final version). Overall, India anticipates generating more power from coal throughout the decade than the draft version. It could be that market forces intervene and this additional coal is not built, but for now, it sends the wrong message regarding the needed coal phase out.

A further challenged to phasing out coal is India's young coal fleet: the average age of coal plants ranges from 13 to 15 years (IEA, 2020a). Between 2010 and 2022, a significant amount of new capacity became operational, accounting for 75% of the current capacity (~145 GW) (Global Energy Monitor, 2023b). Without an effective early retirement plan in place, this existing capacity could potentially remain operational for another 40 to 50 years. There is a significant risk that India’s coal infrastructure will become stranded assets in a 1.5°C compatible world (Malik et al., 2020; Montrone et al., 2021).

Many coal power plants struggle with mounting debts and concerns over their financial viability (Chakravarty & Somanathan, 2021). The total financing cost of coal plants under construction is around USD 3tn (Global Energy Monitor, 2023a). The coal-fired power producers and distribution companies in India are facing significant financial losses due to the falling price of solar and wind. Project cancellations are coming faster in the face of a lack of financial viability and the increase in low-cost renewable capacity installations (Buckley & Shah, 2018; Business Standard News, 2021).

Coal consumption reached record highs in 2021 and 2022, with extreme heat pushing electricity demand to record highs (Reuters, 2023a; The Financial Express, 2022). In September 2023, the country reached a record peak in demand of 240 GW (Reuters, 2023f). In September 2023, power stations consumed 71.4 million tonnes of coal, marking a significant increase from the 61.7 million tonnes consumed in the same month in 2022 (ETEnergyWorld, 2023c).

As in previous years, 2023 has also seen the government invoking an emergency law to make power plants burning imported coal to run at full capacity (Reuters, 2022; The Economic Times, 2023d) to meet the late peak in electricity demand India is also increasing its reliance on coal and fossil gas even after the end of the April-July traditional summer period. The government has mandated imported coal plants to operate at full capacity until June 2024, and domestic coal plants are instructed to blend 4% of imported coal until March 2024, due to inadequate domestic supply of coal to meet the increased demand (S&P Global, 2023).

Most of these imported coal-based thermal power plants were shut due to high international coal prices and also because their power purchase agreements (PPAs) did not have adequate provisions to accommodate the escalating generation costs.

As climate change continues to influence weather patterns in India, it is crucial for it to develop a robust power sector demand and supply plan, based on strategic data. This should be based on a transition to renewable energy to meet the peak load, supported by storage infrastructure. In the absence of transferring the peak load to renewable energy sources with infrastructural support, the dependence on coal will persist to fulfil the summer demand.

Coal supply

India is the world’s second largest coal producer after China, but is still a net importer, due to the scale of its demand. The government has been implementing measures to ramp up domestic production so that it becomes a net exporter of thermal coal in the next couple of years. Coal is seen as a core component of India’s energy policy, given its domestic supply, in contrast to oil and gas, of which it is not a significant producer (Mining Technology, 2023; Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, 2023).

In November 2023, India will hold its eighth coal mine auction, with 40 blocks on offer (Times of India, 2023a). Over the past decade, India has conducted auctions for over 150 coal blocks in seven phases. 51 of these blocks, including five commercial mines, are currently operational, and played a crucial role in contributing to a combined production of 116 million tonnes during FY 2022-23 (Times of India, 2023a).

According to India’s Coal Minister, the country is on track to shift from being a net importer of coal to becoming a net exporter of thermal coal, mainly to neighbouring countries like Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan and Sri Lanka, by 2026 (Mining Technology, 2023). Currently India has operational coal terminal capacity of 669 Mtpa and another 246 Mtpa of capacity under construction (Global Energy Monitor, 2022b).

India produced a record high 892 Mt of coal in 2022-23 compared to 778 Mt in 2021-22, up by 14% (Ministry of Coal, 2022; Mint, 2023b). The cumulative coal production between April to October 2023 reached 506.77 Mt, compared to 448.47 Mt during the same period in 2022, a 13% increase (Ministry of Coal, 2023)

India is considering CCUS as an emissions reduction strategy to achieve deep decarbonisation in hard-to-abate sectors and to allow it to continue to use its coal resources (Press Information Bureau, 2022a). However, India has acknowledged, in its LT-LEDS, that CCUS is not a viable technology option for retrofitting existing thermal power plants as it is not cost-effective for India (Government of India, 2022a)

Taxes and subsidies

In India, subsidies are available for both fossil fuels and renewable energy in the form of direct subsidies, fiscal incentives, price regulation and other government support, but overall subsidies for fossil fuels are nine times higher than those for renewables (IISD, 2022). While coal subsidies have been largely unchanged since 2017, they are still approximately 35% higher than subsidies for renewables (V. Garg et al., 2020). Coal India Ltd., a public limited company and largest government owned coal producer in the world, receives USD 2bn subsidy annually (The New York Times, 2022).

A tax on coal (“coal cess”) was introduced in 2010-11, when the government set up the National Clean Energy Fund (NCEF) to provide financial support to clean energy initiatives and technologies. However, the purpose of the NCEF has changed over time. Since 2017, with the introduction of Goods and Services Tax (GST), the coal cess has been replaced with the GST Compensation Cess, which is no longer directed into the NCEF (IISD, 2019). It has been reported that from March 2026 the cess on coal may be restored to its earlier form (Hindustan Times, 2022). India is currently developing a policy framework to facilitate the successful execution of its carbon capture utilisation and storage (CCUS) initiatives. There is also discussion that the NCEF will be used to facilitate access to affordable finance for CCUS projects (Mint, 2023a).

CCS in the power sector is still not a proven technology (IPCC, 2023). CCS is expensive and does not get to zero emissions (capture rates and permanence remain an issue), and investing in it risks stranded assets or a lock-in of carbon-intensive infrastructure. It may also divert funds that could be otherwise allocated to renewable energy projects. The use of CCS should be limited to industrial applications where there are fewer options to reduce process emissions (Climate Action Tracker, 2023b).

Fossil Gas

The Indian government wants to establish a “gas-based economy” and has set a target of increasing the share of gas in its energy mix from 6% in 2021 to 15% by 2030 (Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, 2021, 2023).

With the planned increase in gas consumption, India will likely need to significantly increase gas imports, as domestic production has remained stagnant (Petroleum Planning and Analysis Cell, 2021). The recent volatility in the fossil gas market price has not deterred it. The CAT has long-cautioned that fossil gas is not a bridging fuel and the current global expansion of LNG could put the 1.5°C limit at risk.

India relies on imports for nearly half of its gas demand, which is increasing as global prices have eased, with a 17.5% rise in import compared to 2022 (LNGPrime, 2023). Dahej terminal, one of the main LNG terminals, is operating at 95% capacity compared to 85% a year before (Reuters, 2023k).

India is looking for more long-term LNG contracts. Petronet LNG Ltd., the largest importer of gas in India, is seeking long-term contracts to purchase an additional 12 Mt of LNG which 60% of current import (Bloomberg, 2023). Gas regulators are also advocating for gas storage development to take advantage of price volatility (Reuters, 2023i). It is important to note that India does not have any strategic reserves for fossil gas.

The government has taken significant initiatives to support the expected import growth through the expansion of LNG terminals and re-gasification capacity, and infrastructure development to facilitate LNG transportation (The Economic Times, 2020; Times of India, 2020).

More than 19,000 km of gas pipelines are currently operational and 16,500 km under development, the highest among South and South East Asian countries (Global Energy Monitor, 2022a). India is further developing 67.5 MTPA of import terminal capacity, compared to the current 47.5 MTPA in operation (Global Energy Monitor, 2022a). Investing in capital-intensive gas infrastructure exposes India to risks such as a carbon lock-in, stranded assets, and increased energy import dependency (Climate Action Tracker, 2022b).

Industry is the biggest consumer of fossil gas in India where, apart from being used for energy purposes, it is used as a feedstock for manufacturing fertiliser and petrochemicals. While fossil gas only accounted for 5% of industrial final energy consumption in 2020, the current policies scenario, based on IEA STEPS, shows a doubling of gas use by 2030 and five-fold increase by 2050, reaching 13% of industrial final energy consumption (IEA, 2022).

India’s fossil gas plans are not consistent with a 1.5°C world. India could save billions if it ditched its gas plans and shifted to a 1.5°C compatible pathway (Climate Action Tracker, 2022b).

Fossil gas in power supply

India has 25 GW of gas power capacity, which generated a small fraction of its power in 2022. Historically, fossil gas power has primarily been used for peaking power support, though about half of its current capacity is not operational, as a result of high gas prices (Reuters, 2023f).

The government has no plans to build any new gas-powered facilities and anticipates having roughly the same capacity in 2030.

Under its latest power sector plan, India estimates it will generate 1.7% of its electricity from gas in FY2026 and 1.3% in FY2031 (Ministry of Power, 2023b). These 20230 generation levels are consistent with a 1.5°C compatible world in 2030, but India needs a clear and explicit plan to phase out its remaining capacity post-2030 to remain 1.5°C compatible (Climate Action Tracker, 2023a). India needs to exit fossil gas power by 2040 at the latest.

In the near-term, India is increasingly relying on fossil gas power to deal with the surging summer electricity demand. To meet that increased demand from August 2023, gas-fired power stations with existing power purchase agreements (PPAs) were instructed to continue operations (Reuters, 2023g). The Ministry of Power also opened a bidding process to set up PPAs to procure an additional 4 GW in gas power capacity to cover the anticipated unusually high demand in October and November 2023 (Reuters, 2023f).

Renewables

India is a world leader in new renewable energy (excl. hydro) for both total capacity and generation, often coming fourth after China, the USA and Germany (IRENA, 2023). As of September 2023, India has installed around 130 GW of new renewable energy capacity, 30% of its total capacity, a figure which has quadrupled since 2015 (CEA, 2023). This includes 68 GW of solar and 43 GW of wind energy: about half of its solar capacity has been installed in just the last three years (CEA, 2019, 2023).

The National Electricity Plan 2023 (NEP 2023), adopted in May 2023, envisages adding considerable solar and wind capacity by 2031-32, 311 GW and 82 GW, respectively (Ministry of Power, 2023b). The Plan is consistent with India’s target of achieving 500 GW of non-fossil capacity by 2030. Compared to the draft version, there has been an increase of around 31 GW in the total capacity added for solar in the final version of NEP. On the other hand, the capacity for wind energy has been reduced by 12 GW, resulting in a net increase of 21 GW in non-hydro renewable energy capacity.

As positive as the recent growth and future plans for renewables are, they are not fast enough for 1.5 °C compatibility. To be 1.5 °C compatible, 70-75% of India’s electricity generation should come from renewables in 2030 (Climate Action Tracker, 2023a). It will be less than 50% under the final NEP. International support is pertinent to achieve this.

Solar and wind have become the lowest-cost electricity sources in India, even without subsidies. Large-scale auctions have contributed to swift renewable energy development at rapidly decreasing prices (Schlissel & Woods, 2019). The solar tariff has declined by around 60% between 2016 to 2022 (from USD 0.0786/kWh to USD 0.028/kWh), mainly because of falling capital costs (MERCOM, 2022).

Wind is the second cheapest energy source after solar with a tariff range of INR2.8-3.1/kWh (USD 0.034/kWh to USD 0.04/kWh) in 2022 (GWEC, 2022). It is anticipated that an increased blending of imported coal in electricity generation will push up the thermal electricity tariff by 4.5% (Times of India, 2022). According to Bloomberg, India will need USD 223bn of investment to meet its 2030 renewable capacity target (The Hindu, 2022).

Local manufacturing of solar PV modules is key for achieving a self-reliant energy transition for India. India currently has solar PV module manufacturing capacity of 39 GW and is expected to reach 95 GW by 2025 and 110 GW by 2026, making it the second largest globally (IEEFA, 2023g). This will give India an opportunity to be self-reliant in achieving its 333 GW solar capacity by 2030 plans (Ministry of Power, 2022c).

The Indian government has taken a multifaceted approach to encourage solar module manufacturing. To increase supply of domestically manufactured solar module, the government approved USD 2 bn for a production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme in 2022, aiming to attract another USD 11 bn from private investors (The Economic Times, 2023c). However, the PV module manufacturing sector faces major challenges in terms of over-reliance on imported upstream materials, which makes it difficult to stay price-competitive (IEEFA, 2023a).

To increase the demand for domestically-produced solar modules, the government has increased the goods and services tax (GST) on renewable energy equipment and imposed customs duty of 40% on imported solar modules and 25% on solar cells (IEEFA, 2022). However, due to a shortfall in domestic supply, the government is now considering whether to reduce the customs duty from 40% to 20% (Reuters, 2023d).

Wind power is supported via a Generation Based Incentive, while state-level feed-in tariffs apply for all renewables. Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) are in place that promote renewable energy and facilitate Renewable Purchase Obligations (RPOs), which legally mandate a percentage of electricity to be produced from renewable energy sources.

The Ministry of Power has revised the minimum renewable purchase obligation for the power distribution companies, gradually increasing it from 24.6% in 2023 to 43.33% in 2030 (MERCOM, 2023b). The RPO rates for wind are 0.81-6.94%, 0.35-2.82% for hydro and 23.44-33.57% for solar (Business Standard News, 2022). The Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) has also issued clarifications that Renewable Energy (RE) Generating Stations have been granted ‘must-run’ priority dispatch status which will allow grid operators to prioritise the dispatch of electricity from renewable energy (PIB India, 2021).

In addition to solar and wind energy, large-hydro power is also an important part of India's power generation mix. In 2022, the total capacity of large hydroelectric power stood at 42 GW. According to the National Electricity Plan (NEP) 2023, this capacity is projected to increase to up to 62 GW in 2031 Small hydro adds another 5GW. In recent years, floating solar power plants have become part of India's plans for solar expansion (IEEFA, 2023c).

The government is implementing measures to support the renewable energy sector, including market protection for domestic solar panel production, and falling costs of renewable energy is also advantageous. However, there are concerns that the focus on domestic production and support for coal and fossil gas-based electricity could hinder the transition to renewable energy and potentially lead to increased solar power costs for consumers in the short-term.

Energy storage

Grid-scale energy storage technology will play a critical role in addressing peak demand and India’s energy transition. To meet peak demand in 2031-32, India anticipates needing 74 GW of storage capacity (27 GW pumped storage and 47 GW battery storage) (Ministry of Power, 2023b). The government is implementing policies to support the expansion of storage capacity, including some funding in the latest budget, but additional measures will be necessary to fulfil the targets outlined in the government's latest electricity plan and with international support, it could expedite faster reductions to accelerate progress towards achieving compatibility with the 1.5°C climate goal.

The 2023-24 National budget includes provisions for 4 GWh of battery storage, through its Viability Gap Funding (VGF), aims at supporting battery manufacturing projects that are economically justified but fall marginally short of financial viability, now has been approved by the cabinet (PMIndia, 2023). But this is not enough to meet the country’s longer-term storage capacity requirement anticipated under the recently-adopted national electricity plan (ET EnergyWorld, 2023; Ministry of Power, 2023b).

Draft guidelines for pumped storage projects (PSPs), first circulated in early 2023 for consultation, have now been finalised and adopted (Ministry of Power, 2023a). India has around 4.7 GW of installed PSP capacity, but its electricity authority estimates that the total PSP potential is over 100 GW. The guidelines should help in the development of additional PSP capacity.

However, concerns expressed by environmental experts over the exemption from environmental clearance of PSPs located in old dams and off-the-river have not been taken into account (Ministry of Power, 2023a; Mongabay, 2023).

In July 2022, India introduced an Energy Storage Obligation as part of its broader RE purchase requirements (Ministry of Power, 2022d). The Energy Storage Obligation (ESO) requires that an increasing percentage of RE comes from stored wind and solar power, starting at 1% in 2023-2024 and rising to 4% by 2029-2030. However, in the latest revision of RPO rates there is no energy storage obligation (MERCOM, 2023b).

In 2022, India and USA jointly launched an energy storage taskforce to support the integration of new renewable energy resources (ETEnergyWorld, 2022a). This collaboration will support technology development and deployment of large-scale integration of renewable energy and facilitate private investment.

The National Green Hydrogen Policy (more below) also envisages using green hydrogen as a storage option.

Green hydrogen

India launched its National Green Hydrogen Mission in 2021 (Ministry of Power, 2022b). In January 2023, the mission was updated, with a focus on the development and deployment of green hydrogen with an investment support of USD 2.3bn by the government, which includes production-linked incentives for the manufacturing of electrolysers and production of green hydrogen (Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, 2023). With this plan, India expects to reach 5 MMT (Million Metric Tonnes) of green hydrogen capacity by 2030 (The Economic Times, 2023a).

India aims to become a major exporter of green hydrogen and wants to capture about 10% of the global green hydrogen market by 2030 (Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, 2023). India has already signed an MoU with Singapore to export green hydrogen from 2025 (The Economic Times, 2022). The government has been engaging with key international markets, such as Europe and Japan, to explore opportunities for collaboration and to identify potential export markets for green hydrogen (DownToEarth, 2023; European Investment Bank, 2023). However, green hydrogen is a nascent technology in India and its commercial viability largely depends on the reduction of electrolyser costs and the availability of round-the-clock renewable energy (IEEFA, 2023d). The government has started auctions under a production-linked incentive programme for electrolyser manufacturing (Reuters, 2023j).

Several Indian and international companies are investing in green hydrogen production to meet India's hydrogen production and export targets. Adani New Industries and TotalEnergies will invest USD 49bn in green hydrogen over the next decade. L&T, Indian Oil, ReNew Power, and NTPCL are also working on various projects related to green hydrogen production and fuel cells (Telematic Wire, 2023). It is expected that the support from the government and these investments may lead to a decrease in production costs in the coming years.

Previously, the government had waived the inter-state transmission charge for 25 years for green hydrogen producers for projects set up before 2025. This waiver has now been extended for hydrogen manufacturing plants commissioned before 2031 (Reuters, 2023e). India’s largest oil refiner, Indian Oil Corporation, estimates that these policy measures will help to reduce the cost of green hydrogen production by 40-50% (Business Standard, 2022).

The mandate for green hydrogen purchase has been brought back under consideration for the fertiliser and refinery industries, previously shelved because with increased price of LNG the cost of green hydrogen became competitive with grey hydrogen (Hydrogeninsight, 2023). According to an assessment by NITI Aayog, the adoption of green hydrogen (produced domestically) has a cumulative mitigation potential of 3.6 GtCO2 by 2050 compared to the use of grey hydrogen (Raj et al., 2022). As a sign of increasing policy support for green hydrogen, at the sub-national level, many Indian states have also started to developing policies for green hydrogen hubs (IEEFA, 2023b).

Industry

In 2022, industrial process emissions accounted for 9% of total emissions (excl. LULUCF) and have been increasing since 1990 at an annual rate of 4% (Gütschow & Pflüger, 2023). India's industrial sector accounts for the largest share of total primary energy demand, at 38% in 2021, growing at an annual rate of 5% over the last 10 years. 1.5°C compatible pathways show the share of electricity in the industrial energy mix increasing between 30-31% by 2030 compared to 2019 (Climate Analytics, 2021). Electrification of industry is essential to decrease the use of fossil gas and limit the need for green hydrogen, which requires various conversion steps, leading to a much lower efficiency in the process compared to using renewable electricity directly. India needs international support to achieve this.

Energy efficiency

The Indian government amended the 2001 Energy Conservation Act in late 2022 (having last made revisions to the law in 2010). The Act regulates energy consumption by equipment, appliances, buildings and industries. The major amendments include:

- An obligation to use non-fossil sources of energy for industry, transport, buildings

- Carbon trading

- Energy conservation code for buildings, both commercial and residential

- Standards for vehicles and vessels

- Allotment of regulatory powers of State Electricity Regulatory Commissions

- Changes in the governing council of the Bureau of Energy Efficiency

The Act mandates the use of non-fossil fuel sources for industries such as mining, steel, cement, textile, chemicals and petrochemicals. The amendments also allow industries to buy renewable energy directly from the producers enabling renewable energy producers price certainty.

The main instrument to increase energy efficiency in India’s industry is the Perform, Achieve and Trade (PAT) Mechanism, which has been in place since 2012 and is implemented under the 'National Mission on Enhanced Energy Efficiency’. It covers 13 energy intensive sectors and nearly 25% of the energy use. The first cycle of the PAT scheme resulted in savings of 5.6 GW and 31 MtCO2e between 2012 and 2015 (BEE, 2018). The second cycle of PAT (2016-17 to 2018-19) resulted in total savings of approximately 61.34 MtCO2e emissions, resulting in savings of INR 800bn.

Industry is the biggest consumer of fossil gas in India where, apart from being used for energy purposes, it is used as a feedstock for manufacturing fertiliser and petrochemicals. Green hydrogen is going to play an important role in decarbonisation of these industries (Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, 2023). While fossil gas only accounted for 5% of industrial final energy consumption in 2020, the current policies scenario, based on IEA STEPS, shows a four-fold increase in gas use by 2050, reaching 10% of industrial final energy consumption, this is an improvement from previous assessment of 13% (IEA, 2022, 2023).

In 2021, the government was planning to introduce a mandatory ‘green hydrogen purchase obligation’ for the industrial users, particularly for refineries and fertiliser plants (Verma, 2021). Now there is a reversal of this earlier thinking. The government believes the market will drive demand as green hydrogen produced in India is currently competitive with grey hydrogen produced with imported LNG. Those within the industry argue that a mandate is essential to instil confidence in financiers regarding the sustainability of demand, especially given that the domestic green hydrogen sector is still in its early stages (The Hindu BusinessLine, 2023).

Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) contribute around 30% of India’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), 40% of its exports and they consume 20-25% energy consumption of the heavy industries (IEEFA, 2023f). BEE has organised several initiatives to address awareness and to provide training and capacity building for implementing energy efficiency measures in MSMEs. MSMEs are struggling to secure financing for decarbonisation efforts. This is particularly concerning as MSMEs have the potential for significant emission reductions as they currently rely on outdated technologies and are not covered by existing climate policies.

The Indian government plans to launch a pilot carbon market mechanism for MSMEs and the waste sector (Ministry of Power, 2022a). During the stakeholder consultation on the framework of India's proposed carbon market, there has been a proposal to allow the voluntary participation of MSMEs (Global, 2023). India has signed an MoU with the Growth Triangle Joint Business Council created by Indonesia, Thailand, and Malaysia to encourage private investments in MSMEs for the adoption of energy efficiency measures (The Financial Express, 2023).

1.5°C compatible pathways for India show the share of electricity in industrial energy mix to reach between 30-31% by 2030 from the 2019 level of 19% (Climate Analytics, 2021). However high industrial electricity prices in India often act as a barrier to the adoption of technologies that could enable the electrification of industries (IEA, 2020b).

Transport

In 2022, India's transport sector consumed 16% of total primary energy but only 1.5% of electricity (IEA, 2023). The transport sector is completely dominated by fossil fuels (96% in 2021), mostly oil (93%). 1.5°C compatible pathways requiring a rapid electrification of the sector show a share of electricity in the total energy mix reaching 10-60% by 2030 and 44-89% by 2050 (Climate Analytics, 2021).

Several national programmes, including the National Urban Transport policy and the Smart Cities Mission, have been established to reduce vehicle traffic and increase transport efficiency.

Electric vehicles

By 2030, India aims to increase the share of electric vehicle (EV) sales to 30% in private cars, 70% in commercial vehicles, 40% in buses, and 80% in two and three-wheelers (Clean Energy Ministerial, 2019; The Economic Times, 2021). At COP26, India signed the 100% EV declaration with a focus on two and three-wheeler auto-rickshaws. The government plans to mandate all two-wheelers to be electric by 2026, ahead of the timeline set at COP26 (Pnadya, 2022).

In 2021, EVs accounted for only 1% of new car sales, but in 2022, the number of registered EVs tripled to 1.01 million, mostly two and three-wheelers (Reuters, 2023b). Financing and the installation of five million fast chargers are crucial for accelerating the transition to e-mobility.

A study by CEEW-Centre for Energy Finance, predicts that the Indian EV market will grow at a compounded annual rate of 36% until 2026 (Bhardwaj, 2021). To be compatible with 1.5°C, the share of EV sales (including two and three wheelers) needs to be between 80-95% by 2030, and 100% by 2040 (Climate Action Tracker, 2020).

Back in 2015, the Indian government launched National Electric Bus Programme (NEBP) with an aim to deploy an additional 50,000 new e-buses (UITP, 2022). However, the success of the electric bus programme faced obstacles due to the low bankability of electric bus leasing contracts caused by the weak financial condition of Indian State Transport Undertakings (STUs) (IEEFA, 2023e). A recent report by the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas recommends that diesel city buses be prohibited in urban areas as part of a 10-year plan to transition towards cleaner fuel for urban public transport and intercity buses to shift towards all-electric buses with CNG/ LNG as transition fuels (Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, 2023).

The Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Electric Vehicles in India (FAME) scheme is a key component of India’s EV strategy. It came into effect in April 2019, with financial support of INR 100bn (USD 1.35bn) to provide incentives to purchase electric vehicles and support for establishing the necessary charging infrastructure (Business Today, 2019).

The scheme hopes to support one million electric two-wheelers, 500,000 electric three-wheelers, 55,000 electric cars, and 7,090 electric buses through subsidies. In 2021, this scheme was extended until 2024, as it had made minimal progress in achieving these sales targets (Chaliawala, 2021). A vast network of EV charging station is needed to support the rapid uptake of EVs. The 2023-24 budget allocated USD 632 million for FAME program, about an 80% increase from previous budget allocations (IEEFA, 2023h).

Fuel standards

India strengthened its fuel/emissions standards in April 2020, when it adopted Bharat Stage VI emissions standard for vehicles (the same as Euro VI standards) (DieselNet, 2021). BS VI is applicable to all vehicles with a Gross Vehicle Weight (GVW) of more than 3,500 kg, including commercial trucks, buses and on-road vocational vehicles such as refuse haulers and cement mixers.

The Indian government has advanced different targets and policy frameworks to introduce alternative fuels in the transport sector to reduce emissions. Blending of 20% ethanol in petrol is part of such an initiative, for which the target year was slashed to 2025 from the earlier target of 2030 (NITI Aayog, 2021).

Similarly, hydrogen is also seen as a potential clean energy source for the transport sector, with hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles particularly for long distances for ships and potentially trucks which cannot always be electrified (Kukreti, 2021; Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, 2021). Toyota has initiated a pilot project to test its hydrogen fuel cell-powered light vehicle on Indian roads (ET Auto, 2023).

In contrast to these steps forward, in its draft LNG policy 2021 the government is developing plans to use LNG in long-haul heavy-duty trucks and other similar vehicles.

The Government has also launched a voluntary vehicle scrappage policy in April 2022 to phase out old vehicles from Indian roads (A. Garg, 2022). The 2023-24 budget includes provisions for scrapping of Central and State Government vehicles that are over 15 years old, as well as tax incentives for private individuals who exchange their old vehicles by purchasing new ones (Times of India, 2023b). However, the new vehicles to be purchased are mostly fossil fuel-driven, as under the policy there is no requirement to replace them with electric vehicles.

Railways and waterways

In July 2020, India railways announced plans to achieve net zero emissions by 2030. In February 2023, Indian Railways has achieved 100% electrification of its network (International Railway Journal, 2023). Indian Railways is also planning to increase its use of renewable energy and will install 30 GW of renewable energy capacity by 2030 (Bloomberg, 2022).

However, only 245 MW solar capacity installation has been executed on rooftops of various stations and administrative buildings to date. Indian Railways also has a goal of mitigating 60 MtCO2e by 2030 by implementing a range of measures, such as planting trees on unoccupied railway areas, decreasing water usage, and constructing facilities that convert waste into energy (Bloomberg, 2022).

Indian Railways is looking to introduce hydrogen-fuelled trains on its narrow gauge heritage routes by the end of this year and has issued tenders for procuring 35 trains powered by green hydrogen (Railway Technology, 2023; The Economic Times, 2023b). Rollout of green hydrogen driven trains in India will still be subject to the cost competitiveness of the fuel (ETEnergyWorld, 2022b).

According to the Maritime India Vision 2030, the ports of India have a target to reduce carbon emission by 30% of per tonne of cargo handled by 2030 (Ministry of Ports Shipping and Waterways, 2021). In November 2022, the first National Centre of Excellence for Green Port & Shipping was launched to provide policy and regulatory support to the Ministry of Ports, Shipping and Waterways for developing regulatory framework and alternate technology adoption roadmap for green shipping to foster carbon neutrality and circular economy in shipping sector in India (Press Information Bureau, 2022b).

Buildings

Per capita building-related emissions in India were nearly four times lower than the G20 average in 2021, reflecting low energy consumption in building sector due to lack of access to the modern appliances (CTR, 2022). But energy consumption from residential buildings is predicted to rise by more than eight times by 2050, hence it is of vital importance for India to develop energy-efficiency strategies focused on the residential sector (Climate Analytics, 2021).

In the last few years, space cooling has become a major source of energy demand from the urban building sector as summer temperatures increase. Governmental initiatives like the Energy Conservation Building Code (ECBC), voluntary initiatives on green building guidelines and a push for the adoption of thermal performance in building design, and construction materials can help reduce the internal heat load and lower space cooling requirements in buildings (BEE, 2021).

The Energy Conservation Act 2022 amendment has expanded the scope for the buildings sector as it now includes offices and residential buildings, with a minimum connected load of 100 kW. The amendment of Energy Conservation Act has changed ECBC to “Energy Conservation and Sustainable Building Code”, which specifies norms and standards for energy efficiency, use of renewable energy and other sustainability-related requirements for different types of buildings.

Energy Efficiency Services Limited (EESL), an initiative of the Ministry of Power, is implementing the Buildings Energy Efficiency Programme to retrofit commercial buildings in India with energy efficiency devices. This programme has delivered an estimated cumulative energy savings of 790 GWh, with avoided peak demand of 75.64 MW, cumulative emissions reduction of 0.65 MtCO2 per year and an estimated cumulative monetary savings of INR 6.8 bn in electricity bills (Ministry of Power, 2022e).

Agriculture

Agriculture is the second highest emitting sector in India after energy, contributing around 14% of total emissions (excluding LULUCF) (Gütschow & Pflüger, 2023). Given that well over half of India’s population generates an income from agriculture, this sector is particularly important. It is also intricately linked to the power sector, as electricity is used for water pumping in modern irrigation. The heavily-subsidised power supply to agriculture has contributed to the use of inefficient pumps and a resulting excessive use of both water and power (Sagebiel et al., 2015).

Demand Side Management (DSM) has been recognised as one of the major interventions to achieve energy efficiency in India’s agricultural sector (MoEFCC, 2021). In 2023, the Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE) launched Agricultural Demand Side Management (AgDSM) to reduce overall power consumption, improve efficiencies of ground water extraction, and reduce subsidy burden on power utilities (BEE, 2023). The PM-KUSUM (Pradhan Mantri Kisan Urja Suraksha evam Utthan Mahabhiyan) scheme aims at setting up 10 GW decentralised grid-connected solar capacity in barren land, along with 17.5 million solar pumps to reduce use of diesel in agricultural activity (MNRE, 2020). The government has extended PM-KUSUM scheme until March 2026, as its implementation was significantly affected by the pandemic (The Economic Times, 2023e).

The government has also implemented measures to reduce N2O emissions associated with fertiliser (urea) use and has programmes in place to assist farmers in reducing emissions and building resiliency (Department of Fertilizers, 2022).

Forestry

India’s first NDC set a target of 2.5–3 GtCO2e of additional carbon sink by 2030, which was reconfirmed in its 2022 update. To achieve that target, a comprehensive forest policy is essential.

On July 2023, the Forest (Conservation) Amendment Bill 2023 was passed by the lower house of the parliament, but has not yet been approved by the upper house (PIB India, 2023). This amendment of the 1980 Forest Conservation Act (FCA) has acknowledged the role of forest carbon sinks in achieving net zero target by 2070, but it has been criticised by various quarters, including government opposition members, former officials, and environmentalists (ETEnergyWorld, 2023a). In the absence of a legislatively defined definition of forests in India, this amendment proposes the removal of FCA protection for private forest land and unrecorded forested parcels.

This amendment exempts the construction of 'linear projects' within 100 km of disputed national borders from the Forest Conservation Act (FCA). This exemption is particularly significant due to the vulnerability of the Himalayan region in the north and northeast of the country, which is part of a global biodiversity hotspot (Third Pole, 2023). It carries important implications for the environmental resilience of these areas. The bill also eliminates pre-clearance checks, such as seeking consent from indigenous inhabitants, for affected lands. It also opens up forests for activities like eco-tourism zones and zoos, raising concerns about potential ecological impact (Third Pole, 2023).

The National Mission for a Green India was launched in 2014 to protect, restore and enhance India’s forest cover as a response to climate change. Under this mission, the aim is to convert 10 mha of forest and non-forest land to increase the forest cover and to improve the quality of existing forest. It is expected to enhance carbon sequestration by about 100 MtCO2e (Ministry of Environment, 2022).

As of 2021, forest and tree cover accounts for 24.6% of India’s land mass. Between 2019-2021, India added about as much forest cover as it lost (Ministry of Environment Forest and Climate Change, 2022). Mining, road construction and irrigation all contribute to forest cover loss (CNBCTV18, 2022).

In 2022, the Forest Conservation Rules were adopted to implement the Forest Conservation Act (FCA), 1980. However, the implementation of these new rules will permit private developers to clear forests without obtaining prior permission from the forest dwellers (Down To Earth, 2023).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter