Policies & action

CAT rates India’s current policies and action as “Insufficient” when compared to its fair share contribution. The “Insufficient” rating indicates that India’s climate policies and action in 2030 need substantial improvements to be consistent with the 1.5°C temperature limit. If all countries were to follow India’s approach, warming would reach over 2°C and up to 3°C.

India will need to implement some additional policies with its own resources to make a fair contribution to addressing climate change but will also need international support to implement all the policies necessary for 1.5°C compatibility.

Further information on how the CAT rates countries (against modelled domestic pathways and fair share) can be found here.

Policy overview

The CAT estimates that India’s emissions will be around 4.0-4.3 GtCO2e in 2030 under current policies.

India’s climate policy is spread across several policy documents, sector-specific strategies and laws with the National Action Plan for Climate Change (NAPCC) serving as the overarching guidance for these efforts. In 2023 some very important policy documents and laws covering the energy sector emerged, including the National Electricity Plan 2023 (NEP2023), the National Green Hydrogen Mission and the recently amended Energy Conservation Act (Ministry of Law and Justice, 2022; Ministry of New And Renewable Energy, 2023; Ministry of Power, 2022c). These documents and laws play a crucial role in shaping the energy landscape.

There has been a steady increase in the deployment of renewable energy in the country, including both utility-scale and rooftop solar. Due to this consistent growth, the share of coal capacity has dropped below 50% for the first time.

This milestone reflects the growing shift towards cleaner energy sources, supported by an impressive 83% increase in investment in renewable energy projects during 2023-24. Large-scale renewable energy projects are gathering momentum, with 69 GW of capacity, primarily solar power, currently out for tender—surpassing the government’s target of 50 GW. Meanwhile, rooftop solar installations are on the rise, with a projected addition of 4 GW in fiscal year 2024. This growth is largely driven by favourable policies and financial mechanisms (Economic Times, 2024b).

However, this increase in renewable energy capacity is barely able to keep up with the surging demand. As a result, the generation share of renewable energy, including large hydro, remains around 18%, showing no improvement since last year (CEA, 2024a). To further accelerate the transition to renewable energy, the government has initiated viability gap funding (VGF) of approximately USD 893m for offshore wind energy projects, signalling its commitment to diversifying and strengthening the renewable energy mix.

Additionally, regional disparity has been observed in renewable energy deployment in the country, where southern states are leading the trend with higher renewable energy potential and a strong state-level policy push (Economic Times, 2024e). This could be a potential risk to a just transition away from coal, as most of the coal mines and thermal power plants are in the central to eastern part of the nation.

It has been anticipated that India will see a more than 83% increase in investments in renewable energy projects to around USD 16.5bn in 2024 (Business Standard, 2024b). India’s fossil fuel companies have also started to diversify their investment into the renewable energy sector (Economic Times, 2024c; MERCOM, 2024) .

India has not yet committed to phasing out coal power or committing to a future without fossil gas. Last year, the government adopted the National Electricity Plan, which indicated a pause in coal capacity addition, at least in the short run (Ministry of Power, 2023b). However, this is not being realised, as the current capacity under construction exceeds what the plan proposes (Global Energy Monitor, 2024). While the government has abandoned plans to add more gas power to its electricity generation, it has increased the utilisation of existing gas power plants to meet energy demands due to severe heat stress.

India is again experiencing extreme summer temperatures in 2024, as in previous years. The peak demand in May reached approximately 246 GW, surpassing last year’s peak of 243 GW. It is projected that India’s peak demand in 2024 will reach 260 GW. Power consumption spiked by 14% in May 2024 compared to the same period in the previous year (CEA, 2024a).

To meet this increased energy demand, there has been a steady rise in the domestic production and import of both coal and fossil gas. While this may be necessary for short-term energy demand, it poses significant risks for long-term energy security due to the volatility of global fossil fuel markets, potential supply disruptions, and the environmental and economic consequences of continued reliance on fossil fuel energy sources.

India has a new government, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, now beginning his third term. This continuity in leadership is anticipated to sustain policy consistency in India's renewable energy sector and maintain momentum in these areas.

Under Modi’s administration, there has been a marked decline in subsidies for the oil and gas sectors (IISD, 2024). It is important that similar reductions will be applied to the coal sector. Ministers in Modi's government have repeatedly emphasised that they will not compromise on power for growth, planning an 80 GW addition to coal power capacity by 2031-32 (PIB, 2023). This suggests a potential status quo in policies related to the thermal power sector and domestic coal production.

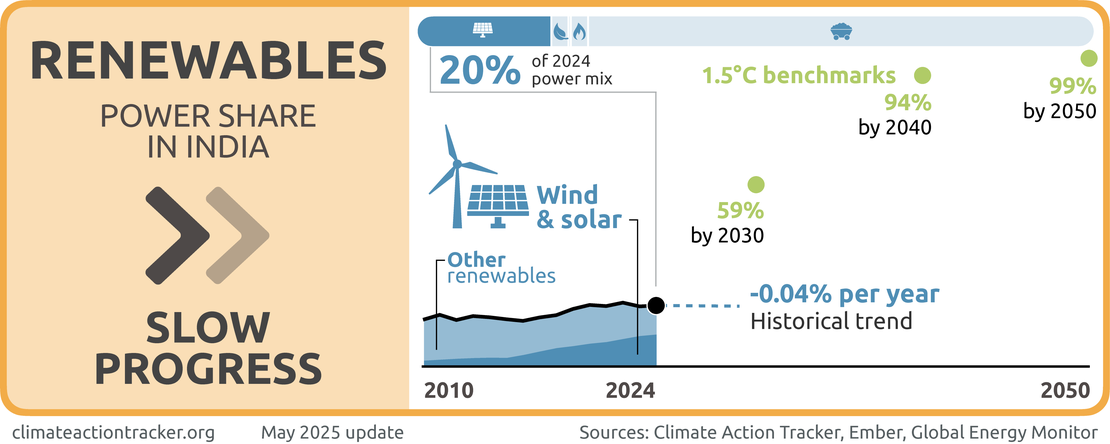

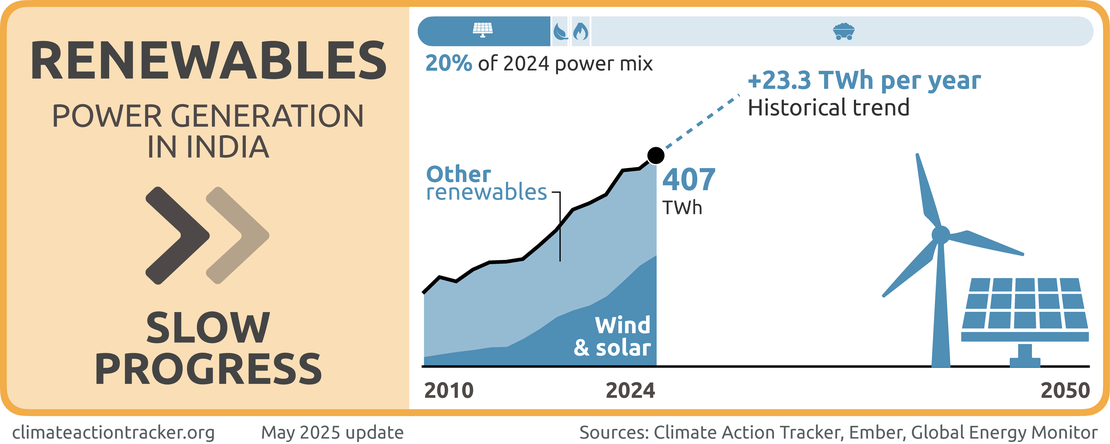

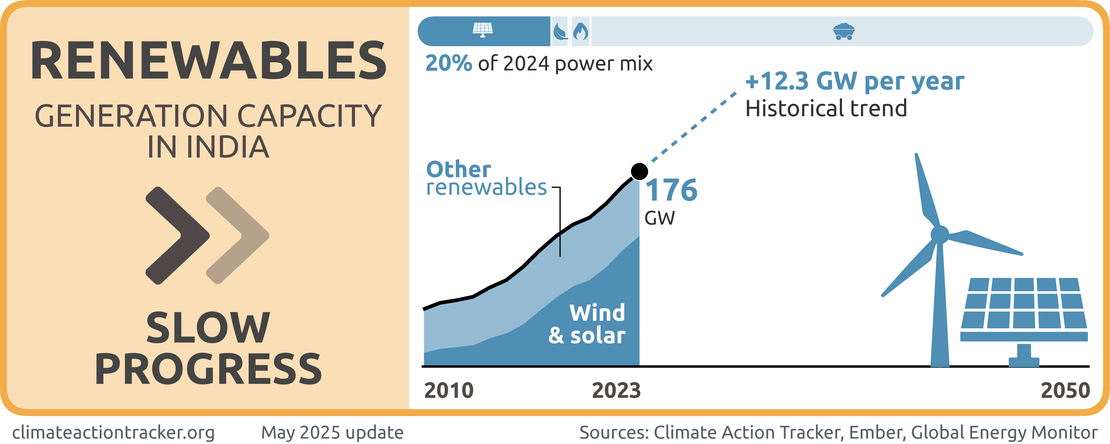

Power sector

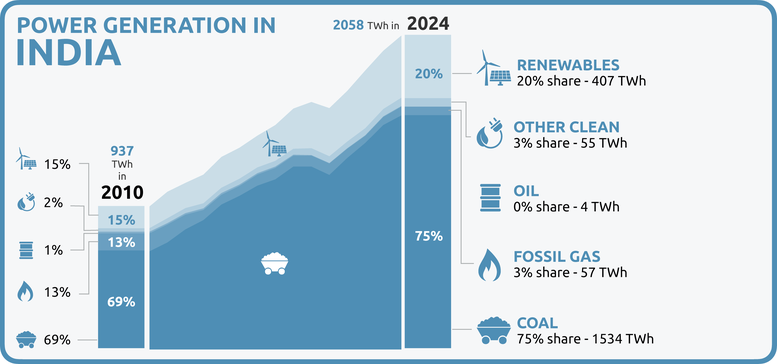

India is heavily reliant on coal power which represents 75% of the country's current electricity generation. Renewables make up the second largest share of India’s power generation at 20%. In the last five years, both coal and renewables have increased significantly in terms of absolute power generation, but their shares of power generation have remained close to constant. This indicates that the steady growth in renewable capacity generation is more a response to a steadily growing increase in electricity demand rather than a specific effort to decarbonise the power sector.

In recent years, extreme heat has pushed electricity demand to record highs. Peak electricity demand reached approximately 246 GW in May 2024, surpassing the previous high of 243 GW from September 2023 (Mint, 2024b). Power consumption increased by 14% in May 2024 compared to the previous year (CEA, 2024a), leading to increased domestic production and import of both coal and fossil gas.

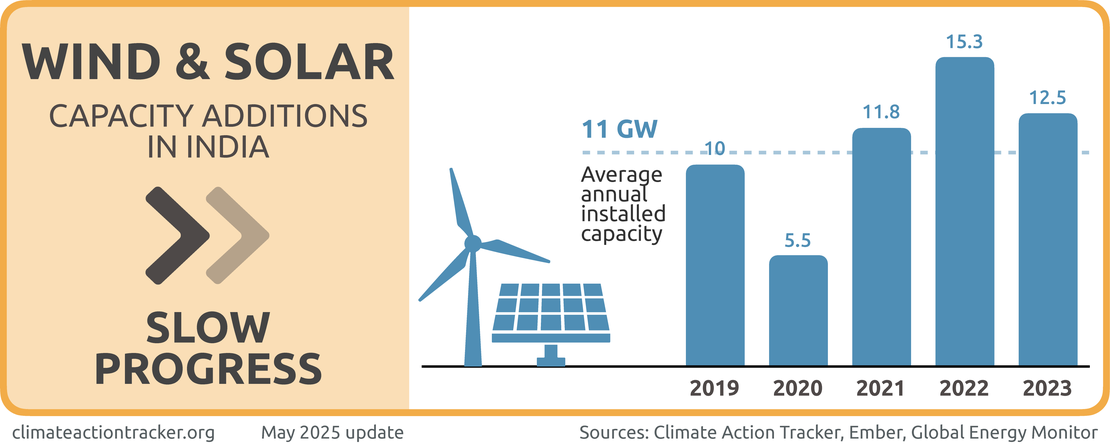

India has made significant progress in renewable energy deployment increasing the total renewable generation capacity to around 175 GW installed as of 2023, representing 37% of its total generation capacity (Ember, 2025). This includes 47 GW of hydro, 10 GW of bioenergy, 45 GW of wind, and 73 GW of solar, with about half of its solar capacity installed in just the last three years (CEA, 2019, 2023). Over the last five year, India has also been installing more new annual generation capacity for wind and solar than for coal at an average of 11 GW compared to 3.9 GW respectively. However, renewable energy generation (including large hydroelectric capacity) struggles to keep pace with surging demand and remains at about 18% of the total power mix (Ember, 2025).

The reasons for low renewable power generation despite high generation capacity are manyfold. Rapid electricity demand growth means that fossil fuels are still needed to meet a significant portion of the increased demand, keeping their overall share high relative to renewables in the total mix. In 2024, for the first time more than 50% of the demand growth has been met through non-fossil sources.

There are also weather-related factors that have caused lower renewables power generation. Storage capacity is still limited, and night demand is mainly met through fossil sources. Lower solar radiation than expected has meant that solar generation has not fully reflected the impact of the generation capacity boom. Wind generation is affected by variable wind conditions year to year. Hydropower generation is significantly affected by drought conditions, though India saw a rebound in hydro in 2024 after a decline in 2023.

Coal

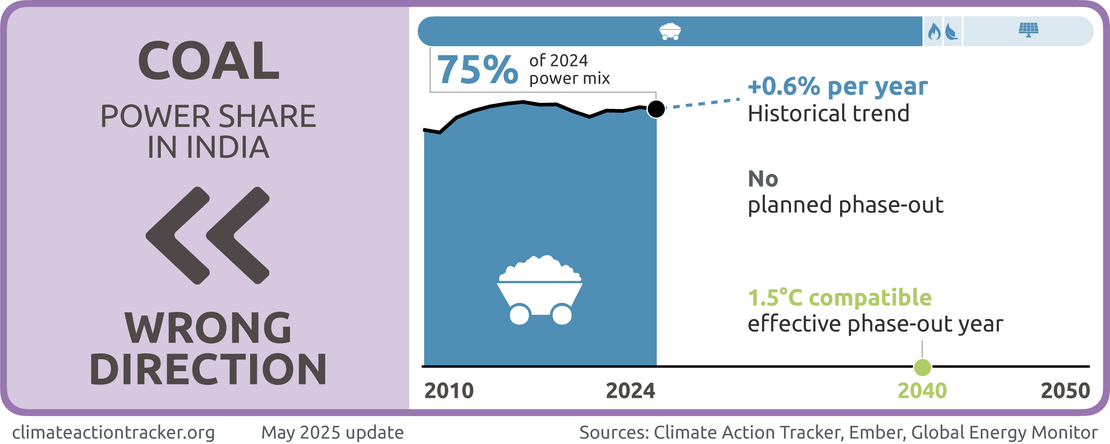

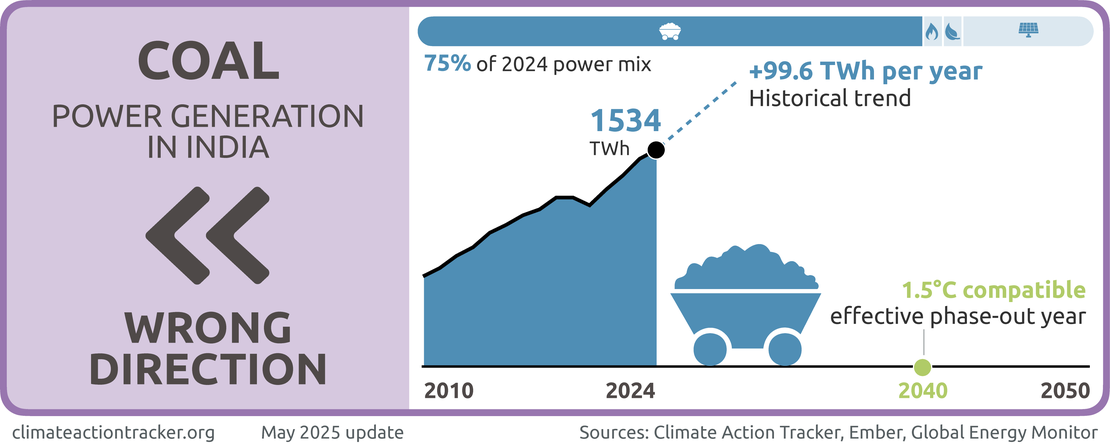

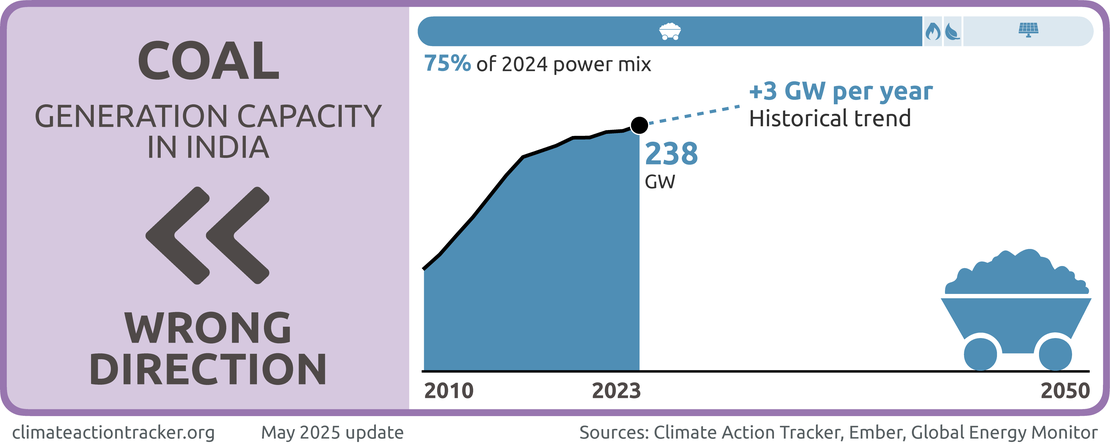

India’s electricity generation is heavily reliant on coal power, which represents over 75% of the country’s current generation, with 27 GW of new coal capacity under construction or in advanced planning and an additional 24.2 GW between 2027-2032 (Ministry of Power, 2023b). Though the share of coal in power generation has stayed consistently around 75% percent, power generated from coal in absolute terms has risen from 1144 TWh to 1534 TWh. This continued reliance on coal is inconsistent with the 1.5°C temperature limit. With significant operational and pipeline coal capacity in place and no clear plan to phase out the current capacity we evaluate progress in this sector as moving in the “Wrong direction.”

To be 1.5°C compatible, India's coal power generation would need to reduce significantly by 2030 (reach 17-19% of total generation) and be effectively phased out by 2040. India will need international support to achieve a transition at this scale.

The Indian government has indicated no plans to shut down any coal power plant before 2030 (Global Energy Monitor, 2024), and indeed is planning to construct more coal capacity. Last year when India adopted its National Electricity Plan (NEP 2023) there was an indication of a pause in new coal capacity addition. According to the NEP, 25.6 GW of coal power is expected to come online by 2026 and an additional 24.2 GW has been planned between 2027-2032.

India has 30.7 GW of new coal power plants either under construction or at advanced stages of planning, and another 11.4 GW capacity addition has been proposed (Global Energy Monitor, 2024). Although India’s coal capacity addition, on a year-on-year basis, has declined significantly since 2015, new capacity addition between 2022 and 2023 has almost doubled compared to previous years. With continuous additions to the coal capacity and an absence of any effective plan for early retirement, it is unlikely that India would be able to witness any “phase-down” soon, it sends the wrong message regarding the needed coal phase-out.

Indian coal power sector is dealing with several challenges such as operational inefficiencies, technological hurdles as reflected by falling plant load factors, decreasing cost competitiveness with renewable energy and financial stress (Chakravarty & Somanathan, 2021), (Buckley & Shah, 2018; Business Standard News, 2021). All these factors create a strong case for the early retirement of the existing capacity. However, a challenge to phasing out coal is India's young coal fleet: the average age of coal plants ranges from 13 to 15 years (IEA, 2020a). Without an effective early retirement plan in place, this existing capacity could potentially remain operational for another 40 to 50 years. There is a significant risk that India’s coal infrastructure will become stranded assets in a 1.5°C compatible world (Malik et al., 2020; Montrone et al., 2021).

Similar to previous years, this year India is again dealing with record summer temperatures, leading to a record peak demand of electricity of 246 GW in May 2024, surpassing previous high of 243 GW from September 2023 (Mint, 2024b).

With extreme heat pushing electricity demand to record highs, coal power generation also reached a record high of 122 TWh in May 2024, owing to a steady increase in power sector emissions (Ember, 2024). In April 2024, power plants consumed 77.1 million tonnes of coal, marking a significant increase from the 71.3 Mt consumed in the same month in 2023 (CEA, 2024b). The National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC), the largest public sector enterprise in coal power generation, is planning to increase annual coal output from its mines, and aims to double production within three years to meet the rising electricity demand (Financial Express, 2024). In the 2024 budget financial assistance has been extended to NTPC for Advanced Ultra Super Critical (AUSC) thermal power plants (Climate Group, 2024).

As in previous years, 2024 has also seen the government invoking an emergency law to make power plants burning imported coal to run at full capacity to meet the peak in electricity demand. India is also increasing its reliance on imported coal. The government mandated plants running on imported coal to operate at full capacity until June 2024, and increased the blending share of imported coal from 4% to 6% until March 2024, later extended to October 2024 (PIB India, 2023a). In the fiscal year 2022-2023 thermal coal imports increased by almost 20% (Ministry of Coal, 2023c).

Most of these imported coal-based thermal power plants were shut due to high international coal prices and also because their power purchase agreements (PPAs) did not have adequate provisions to accommodate the escalating generation costs.

As climate change continues to influence weather patterns in India, it is crucial for it to develop a robust power sector demand and supply plan, based on strategic data. This should be based on a transition to renewable energy to meet the peak load, supported by storage infrastructure. In the absence of transferring the peak load to renewable energy sources with infrastructural support, the dependence on coal will persist to fulfil the summer demand.

Coal production for power

India is the world’s second largest coal producer after China, but is still a net importer, due to the scale of its demand, mainly for power generation. Around 90% of Indian domestic coal is utilised for power generation. The government has been implementing measures to ramp up domestic production and reached a record high of almost one billion tonnes of coal in 2023-24 compared to 892 Mt in 2022-23 (Business Line, 2024)(Ministry of Coal, 2023b). There has been a consistent rise in coal production over the past decade, starting from 565 Mt in 2014 (Ministry of Coal, 2023a). Coal is seen as a core component of India’s energy policy, given its domestic supply, in contrast to oil and gas, of which it is not a significant producer (Mining Technology, 2023; Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, 2023).

In June 2024, India held its tenth coal mine auction, with 60 blocks on offer (Times of India, 2024). Over the past decade, India has conducted auctions for over 160 coal blocks with a combined total peak capacity of 575 million tonne per year.

Fossil gas

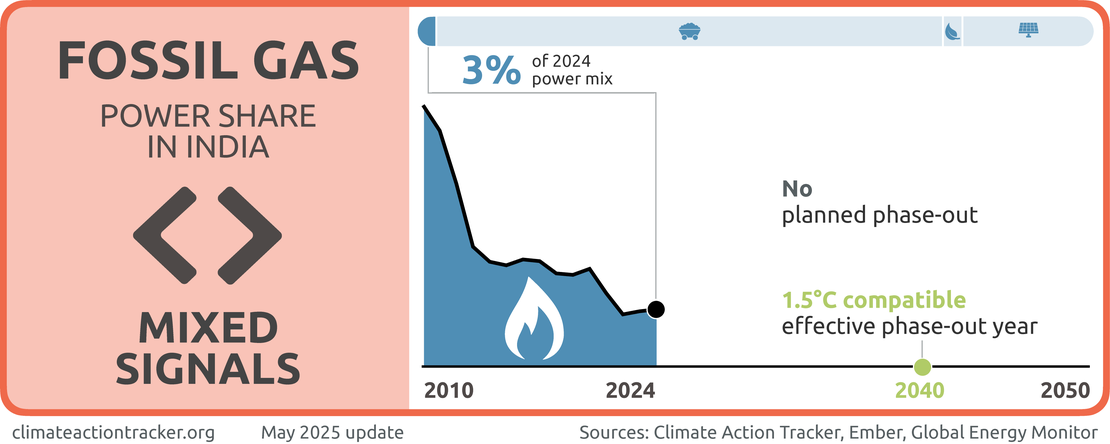

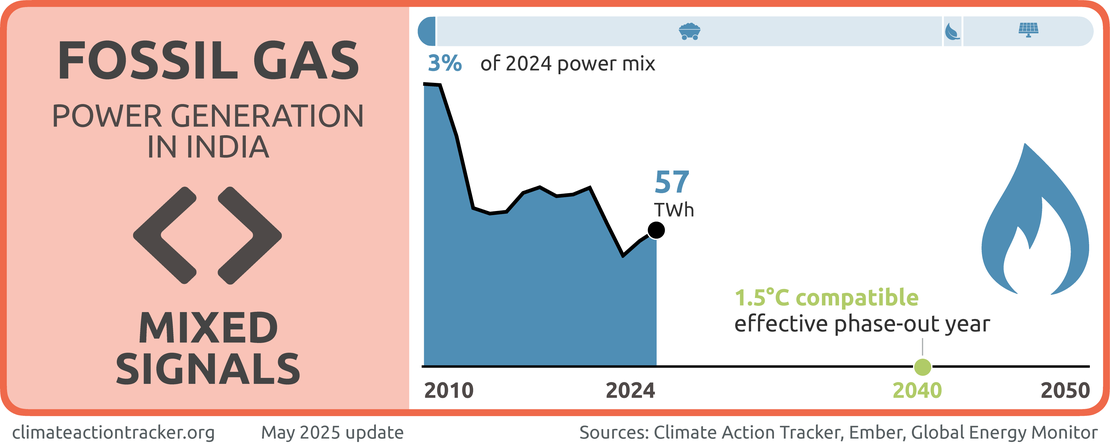

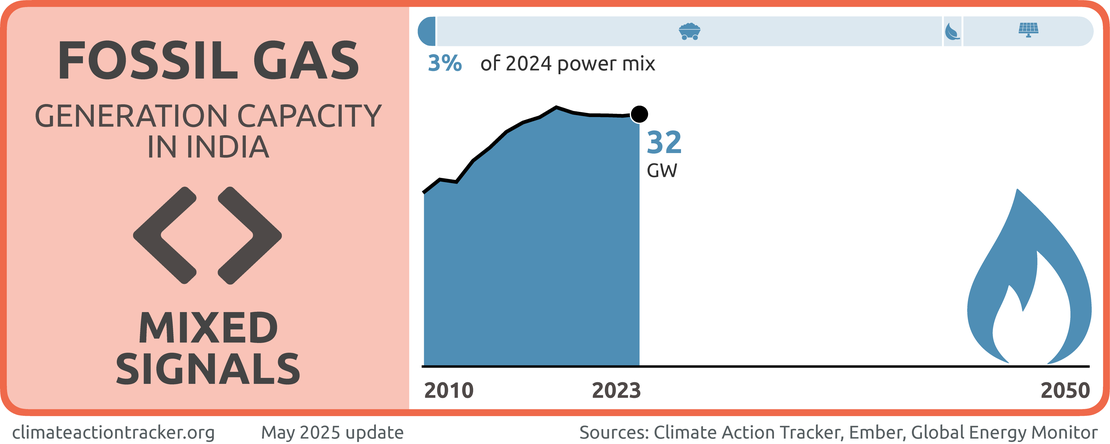

Although the share of fossil gas in the total power generation declined over the last 5 years, the absolute amount of fossil gas generation does see intra-year increases to meet summer peak demand. At the same time, two additional fossil gas-fired power plants are in the pipeline totalling 1270 MW of capacity. We evaluate India’s progress in phasing out fossil gas as sending “Mixed signals.”

In 2016, India announced its intention to be a "gas-based economy" and set a target of increasing the share of gas in its energy mix from 6% to 15% by 2030 (Indian Express, 2016). However, since then, the share of gas in primary energy has increased only marginally to 6.83% in 2020 and fell to 5.7% in 2022 (Energy Institute, 2024).

Under its latest power sector plan, India estimates it will generate 1.7% of its electricity from gas in FY2026 and 1.3% in FY2031 (Ministry of Power, 2023b). These 2030 generation levels are consistent with a 1.5°C compatible world in 2030, but India needs a clear and explicit plan to phase out its remaining capacity post-2030 to remain 1.5°C compatible (Climate Action Tracker, 2023). India needs to effectively exit fossil gas power by 2040 at the latest to be consistent with a 1.5°C world and current plans for fossil gas are not aligned with that.

Gas power plants in India have traditionally been employed for peaking power support. India has 29 GW of gas power capacity. However, their utilisation declined, from 11% in 2010 to 6% in 2021, due to the limited availability of domestic gas supplies (IEA, 2023b). With a surge in summer electricity demand, fossil gas power plants have been brought back online again to provide peak power (Reuters, 2023c; S&P Global, 2024). Most of this increased generation is fuelled by imports, with 45% of total gas used in power plants in the first quarter being sourced from abroad (S&P Global, 2024).

There are two fossil gas-fired power plants in the pipeline, one under construction and one recently under development, totalling 1270 MW planned capacity.

There has also been a policy push to support the uptake of expensive imported gas-based electricity by introducing a High-Price Day Ahead Market (HP-DAM). This market allows electricity to be traded at a high tariff of Rs20 per unit. The idea was to make it easier for power producers using costly imported fuels to sell their electricity at a price that reflects their higher production costs (IEEFA, 2024a).

Gas infrastructure

The government has taken significant initiatives to support the expected import growth through the expansion of LNG terminals and re-gasification capacity, and infrastructure development to facilitate LNG transportation (The Economic Times, 2020; Times of India, 2020). One of the main LNG terminals, the Dahej terminal, is operating at 95% capacity compared to 85% a year before (Reuters, 2023g). The Gas Authority of India Ltd (GAIL) is also planning to double the capacity of its LNG terminal in Dhabol (Offshore Technology, 2024).

More than 19,000 km of gas pipelines are currently operational and 20,857 km under development, the highest among South and South East Asian countries (Global Energy Monitor, 2023). India is developing a further 67.5 MTPA of import terminal capacity, compared to the current 47.5 MTPA in operation (Global Energy Monitor, 2022). Investing in capital-intensive gas infrastructure exposes India to risks such as a carbon lock-in, stranded assets, and increased energy import dependency (Climate Action Tracker, 2022).

Industry is the biggest consumer of fossil gas in India where, apart from being used for energy purposes, it is used as a feedstock for manufacturing fertiliser and petrochemicals. While fossil gas only accounted for 5% of industrial final energy consumption in 2020, the current policies scenario, based on IEA STEPS, shows a doubling of gas use by 2030 and five-fold increase by 2050, reaching 13% of industrial final energy consumption (IEA, 2022).

India’s fossil gas plans are not consistent with a 1.5°C world. India could save billions if it ditched its gas plans and shifted to a 1.5°C compatible pathway (Climate Action Tracker, 2022).

Taxes and subsidies for fossil fuels

In India, subsidies are available for both fossil fuels and renewable energy in the form of direct subsidies, fiscal incentives, price regulation and other government support, but total subsidies for fossil fuels are eight times higher than those for renewables. Overall, India’s fossil fuel subsidies have declined by approximately 70% over the past decade, primarily due to an 80% reduction in oil and gas subsidies (IISD, 2024). While coal subsidies largely declined from 2014 to 2021, they then began increasing, doubling in doubled in 2023 compared to 2021, aligning with the increased coal consumption. Coal India Ltd., a public limited company and the largest government owned coal producer in the world, receives an annual USD 2bn subsidy (The New York Times, 2022).

A tax on coal (“coal cess”) was introduced in 2010-11, when the government set up the National Clean Energy Fund (NCEF) to provide financial support to clean energy initiatives and technologies. However, the purpose of the NCEF has changed over time. Since 2017, with the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST), the coal cess has been replaced with the GST Compensation Cess, which is no longer directed into the NCEF (IISD, 2019). Recently an inter-ministerial committee has proposed a higher cess on imported coal (Business Standard, 2024a).

Renewables

India is in a leading position in new renewable energy (excl. hydro) for both total capacity and generation. India has made significant progress in renewable energy deployment increasing the total renewable generation capacity to around 175 GW installed as of 2023, representing 37% of its total generation capacity (Ember, 2025). This includes 47 GW of hydro, 10 GW of bioenergy, 45 GW of wind, and 73 GW of solar, with about half of its solar capacity installed in just the last three years (CEA, 2019, 2023). Over the past year installation of renewable energy capacity, particularly for solar has shown a sustained increase supported by encouraging policy governance. However, this capacity addition is not reflected in generation at a similar scale and remains at about 18% of the total power mix (Ember, 2025). We evaluate India’s progress in renewables in the power sector as “Slow progress.”

The National Electricity Plan 2023 (NEP 2023), adopted in May 2023, envisages adding considerable solar and wind capacity by 2031-32, 311 GW and 82 GW, respectively (Ministry of Power, 2023b). The Plan is consistent with India’s target of achieving 500 GW of non-fossil capacity by 2030. To achieve these NEP 2023 targets India needs to install around 40GW of solar and wind capacity annually between 2021-22 and 2031-32. This calls for a stronger implementation strategy. According to Bloomberg, India will need USD 223bn of investment to meet its 2030 renewable capacity target (The Hindu, 2022).

As positive as the recent growth and future plans for renewables are, they are not fast enough for 1.5°C compatibility. To be 1.5°C compatible, 52-65% of India’s electricity generation should come from renewables in 2030, increasing to 91-96% in 2040. International support is critical to achieve this.

Solar energy

Large-scale renewable energy projects in India are gathering momentum with 69 GW of mainly solar power out for tender, surpassing 50 GW the government target (IEEFA, 2024c). There has also been a record increase in wind-solar hybrid and energy storage systems, from 16% of total renewable energy capacity tendered in 2020 to 43% in 2024. This increase in utility-scale renewable energy projects calls for more inclusive land acquisition and rehabilitation policies, as an increasing number of farmers’ disappointments are now being reported from previous solar park projects where the promise of additional income, jobs or compensation in return for fertile land was not delivered (DownToEarth, 2023a; Pulitzer Center, 2023).

India is experiencing a significant surge in rooftop solar installations, with a projected addition of 4 GW in fiscal year 2024 (IEEFA, 2024b). This marks a major shift - from being a laggard to a leader in the sector. The growth is driven by various favourable policies and financial mechanisms, particularly for households, which are receiving substantial financial support to install solar rooftop PM Surya Ghar policy (Economic Times, 2024b). Despite regulatory challenges and limited support from local electricity distribution companies (DISCOMs), the sector is poised for robust growth due to declining solar module costs and innovative business models like virtual net metering and peer-to-peer trading (Economic Times, 2024d).

Domestic PV manufacturing

The Indian government has taken a multifaceted approach to encourage solar module manufacturing. To increase supply of domestically manufactured solar modules, the government approved USD 2 bn for a production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme in 2022, aiming to attract another USD 11 bn from private investors (The Economic Times, 2023c). However, the PV module manufacturing sector faces major challenges in terms of overreliance on imported upstream materials, which makes it difficult to stay price-competitive (IEEFA, 2023a).

Local manufacturing of solar PV modules is key for achieving a self-reliant energy transition for India. India currently has solar PV module manufacturing capacity of 39 GW and is expected to reach 95 GW by 2025 and 110 GW by 2026, making it the second largest globally (IEEFA, 2023f). This will give India an opportunity to be self-reliant in achieving its planned 311 GW solar capacity by 2030 (Ministry of Power, 2022c). In recent years, floating solar power plants have become part of India's plans for solar expansion (IEEFA, 2023b).

To increase the demand for domestically-produced solar modules, the government has increased the goods and services tax (GST) on renewable energy equipment and a imposed customs duty of 40% on imported solar modules and 25% on solar cells (IEEFA, 2022). However, due to a shortfall in domestic supply, the government is now considering whether to reduce the customs duty from 40% to 20% (Reuters, 2023a).

Wind energy

Wind is the second cheapest energy source after solar with a tariff range of INR 2.8-3.1/kWh (USD 0.034/kWh to USD 0.04/kWh) in 2022 (GWEC, 2022). It is anticipated that an increased blending of imported coal in electricity generation will push up the thermal electricity tariff by 4.5% widening the gap with cheap solar and wind power (Times of India, 2022).

Wind power is supported via the Generation Based Incentive, while state-level feed-in tariffs apply for all renewables. Recently government has approved viability gap funding (VGF) of around USD 893m for offshore wind energy projects of 1 GW capacity (Deccan Herald, 2024).

Hydropower

Along with solar and wind energy, large-hydro power is also an important part of India's power generation mix. In March 2024, the total capacity of large hydroelectric power stood at 47 GW. According to the (NEP) 2023, this capacity is projected to increase to up to 62 GW in 2031 Small hydro adds another 5 GW. Government has developed a Standard Operational Procedure (SOP) for small and large hydro projects to ensure sustainability (CEA, 2024c).

Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) are in place that promote renewable energy and facilitate Renewable Purchase Obligations (RPOs), which legally mandate a percentage of electricity to be produced from renewable energy sources. The Ministry of Power has revised the minimum renewable purchase obligation for the power distribution companies, gradually increasing it from 24.6% in 2023 to 43.33% in 2030 (MERCOM, 2023). Per technology, these increases were: 0.81% to 6.94% for wind, 0.35% to 2.82% for hydro and 23.44% to 33.57% for solar (Business Standard News, 2022). The Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) has also issued clarifications that Renewable Energy (RE) Generating Stations have been granted ‘must-run’ priority dispatch status which will allow grid operators to prioritise the dispatch of electricity from renewable energy (PIB India, 2021).

Energy Storage

Grid-scale energy storage technology will play a critical role in addressing peak demand and India’s energy transition. To meet peak demand in 2031-32, India anticipates needing 74 GW of storage capacity (27 GW pumped storage and 47 GW battery storage) (Ministry of Power, 2023b). The government is implementing policies to support the expansion of storage capacity, including some funding in the latest budget, but additional measures will be necessary to fulfil the targets outlined in the government's latest electricity plan.

In 2023, a total 4 GW of energy storage tenders were awarded, half of them for pumped storage (IEEFA, 2023g). The Ministry of Power has now released a detailed framework for promoting energy storage systems (ESS), including both pumped and battery storage (Ministry of Power, 2023c). This guideline also advocates for Viability Gap Funding (VGF) in ESS projects, for up to 40% of capital costs, along with other regulatory and economic incentives.

The 2023-24 National budget includes provisions for 4 GWh of battery storage, through its VGF, aimed at supporting battery manufacturing projects that are economically justified but fall marginally short of financial viability (PMIndia, 2023). But this is not enough to meet the country’s longer-term storage capacity requirement anticipated under the recently-adopted national electricity plan (ET EnergyWorld, 2023; Ministry of Power, 2023b).

Guidelines for pumped storage projects (PSPs) have now been finalised and adopted and should help spur additional development (Ministry of Power, 2023a). India has around 4.7 GW of installed PSP capacity, but its electricity authority estimates that the total PSP potential is over 100 GW. However, concerns expressed by environmental experts over the exemption from environmental clearance of PSPs located in old dams and off-the-river have not been taken into account (Ministry of Power, 2023a; Mongabay, 2023).

In July 2022, India had introduced an Energy Storage Obligation as part of its broader RE purchase requirements (Ministry of Power, 2022d). The Energy Storage Obligation (ESO) required that an increasing percentage of RE comes from stored wind and solar power, starting at 1% in 2023-2024 and rising to 4% by 2029-2030. However, in the latest revision of RPO rates, this energy storage obligation appears to have been dropped (MERCOM, 2023).

In 2022, India and the USA jointly launched an energy storage taskforce to support the integration of new renewable energy resources (ET EnergyWorld, 2022a). This collaboration will support technology development and deployment of large-scale integration of renewable energy and facilitate private investment.

The National Green Hydrogen Policy (more below) also envisages using green hydrogen as a storage option.

Renewables tariff

Solar and wind have become the lowest-cost electricity sources in India, even without subsidies. Large-scale auctions have contributed to swift renewable energy development at rapidly decreasing prices (Schlissel & Woods, 2019). The solar tariff has declined by around 60% between 2016 to 2022 (from USD 0.0786/kWh to USD 0.028/kWh), mainly because of falling capital costs (MERCOM, 2022).

However, between 2022 and 2024 a marginal increase in the solar tariff (USD 0.031/kWh) has been observed, mainly due to an increase in the price of solar modules owing to promoting local manufacturing and restricting imports (IEEFA, 2024c). Solar with storage has also become competitive in India: the reverse auction in 2024 saw solar PV with storage posting the lowest bid of USD 0.041/kWh, even lower than the average cost of coal generation which is USD 0.051/kWh (Andy Colthorpe, 2024; Ember, 2023).

Industry

In 2022, industrial process emissions accounted for 9% of total emissions (excl. LULUCF); they have been increasing since 1990 at an annual rate of 4% (Gütschow & Pflüger, 2023). India's industrial sector accounts for the largest share of total primary energy demand, at 38% in 2021, growing at an annual rate of 5% over the last 10 years.

1.5°C compatible pathways show the share of electricity in the industrial energy mix increasing between 30-31% by 2030 compared to 2019 (Climate Analytics, 2021). Electrification of industry is essential to decrease the use of fossil gas and limit the need for green hydrogen, which requires various conversion steps, leading to a much lower efficiency in the process compared to using renewable electricity directly. India needs international support to achieve this. However, high industrial electricity prices in India often act as a barrier to the adoption of technologies that could enable the electrification of industries (IEA, 2020b).

Energy efficiency

The Indian government amended the 2001 Energy Conservation Act in late 2022 (having last made revisions to the law in 2010). The Act regulates energy consumption by equipment, appliances, buildings and industries. The major amendments include:

- An obligation to use non-fossil sources of energy for industry, transport, buildings

- Carbon trading

- Energy conservation code for buildings, both commercial and residential

- Standards for vehicles and vessels

- Allotment of regulatory powers of State Electricity Regulatory Commissions

- Changes in the governing council of the Bureau of Energy Efficiency

The Act mandates the use of non-fossil fuel sources for industries such as mining, steel, cement, textile, chemicals and petrochemicals. The amendments also allow industries to buy renewable energy directly from the producers enabling renewable energy producers price certainty.

The main instrument to increase energy efficiency in India’s industry is the Perform, Achieve and Trade (PAT) Mechanism, which has been in place since 2012 and is implemented under the 'National Mission on Enhanced Energy Efficiency’. It covers 13 energy intensive sectors and nearly 25% of the energy use. The first cycle of the PAT scheme resulted in savings of 5.6 GWh and 31 MtCO2e between 2012 and 2015 (BEE, 2018). The second cycle of PAT (2016-17 to 2018-19) resulted in total savings of approximately 61.34 MtCO2e emissions, resulting in savings of INR 800 bn.

Industry is the biggest consumer of fossil gas in India where, apart from being used for energy purposes, it is used as a feedstock for manufacturing fertiliser and petrochemicals. Green hydrogen is going to play an important role in decarbonisation of these industries (Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, 2023). While fossil gas only accounted for 5% of industrial final energy consumption in 2020, the current policies scenario, based on IEA STEPS, shows a four-fold increase in gas use by 2050, reaching 10% of industrial final energy consumption, this is an improvement from previous assessment of 13% (IEA, 2022, 2023c).

Early suggestions of a mandatory green hydrogen purchase obligation have been silenced given the apparent cost-competitiveness of domestically produced green hydrogen with grey hydrogen made from imported LNG, the latter getting more expensive due to global market volatility (Verma, 2021). This has been met with resistance from the hydrogen industry which argues that mandates are essential for investor confidence to drive scale-up (The Hindu BusinessLine, 2023).

Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) contribute around 30% of India’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), 40% of its exports and 20-25% of its heavy industry energy consumption (IEEFA, 2023e). The Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE) has organised several initiatives to address awareness and to provide training and capacity building for implementing energy efficiency measures in MSMEs. MSMEs are struggling to secure financing for decarbonisation efforts. This is particularly concerning as MSMEs have the potential for significant emission reductions as they currently rely on outdated technologies and are not covered by existing climate policies. In the budget for 2024, the government has extended financial support to MSMEs for shifting to cleaner energy and implementing energy efficiency measures (Climate Group, 2024).

The Indian government plans to launch a pilot carbon market mechanism for MSMEs and the waste sector (Ministry of Power, 2022a). During the stakeholder consultation on the framework of India's proposed carbon market, there has been a proposal to allow the voluntary participation of MSMEs (Global, 2023). India has signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the Growth Triangle Joint Business Council created by Indonesia, Thailand, and Malaysia to encourage private investments in MSMEs for the adoption of energy efficiency measures (The Financial Express, 2023).

Green hydrogen

In India, the push towards green hydrogen is increasingly driven by its vast industrial sector, industries such as steel and fertiliser production are pivotal.

India launched its National Green Hydrogen Mission in 2021 (Ministry of Power, 2022b). In January 2023, the mission was updated, with a focus on the development and deployment of green hydrogen with an investment support of USD 2.3 bn by the government, which includes production-linked incentives for the manufacturing of electrolysers and production of green hydrogen (Ministry of New And Renewable Energy, 2023). With this plan, India expects to reach 5 MTPA per annum of green hydrogen capacity by 2030. (The Economic Times, 2023a). The World Bank recently approved a USD 1.5 bn loan to accelerate green hydrogen in India.

India aims to become a major exporter of green hydrogen and wants to capture about 10% of the global green hydrogen market by 2030 (Ministry of New And Renewable Energy, 2023). It has already signed an MoU with Singapore to export green hydrogen from 2025 (The Economic Times, 2022). The government has been engaging with key international markets, such as Europe and Japan, to explore opportunities for collaboration and to identify potential export markets for green hydrogen (DownToEarth, 2023b; European Investment Bank, 2023). However, green hydrogen is a nascent technology in India and its commercial viability largely depends on the reduction of electrolyser costs and the availability of round-the-clock renewable energy (IEEFA, 2023c). The government has started auctions under a production-linked incentive programme for electrolyser manufacturing (Reuters, 2023f).

Oil India Limited (OIL) recently commissioned India's first 99% pure green hydrogen plant in Jorhat. NTPC has also initiated green hydrogen blending operations in Surat's Piped Natural Gas (PNG) network, starting from a 5% blending to scale up to 20% (Energyworld, 2024). Several Indian and international companies are investing in green hydrogen production to meet India's hydrogen production and export targets. Adani New Industries and TotalEnergies will invest USD 49 bn in green hydrogen over the next decade. L&T, Indian Oil, ReNew Power, and NTPCL are also working on various projects related to green hydrogen production and fuel cells (Telematic Wire, 2023). It is expected that the support from the government and these investments may lead to a decrease in production costs in the coming years.

Additional support comes from a 25-year waiver of the inter-state transmission charge for green hydrogen projects. It previously applied to projects set up before 2025, and has now been extended to for hydrogen manufacturing plants commissioned before 2031 (Reuters, 2023b). India’s largest oil refiner, Indian Oil Corporation, estimates that these policy measures will help to reduce the cost of green hydrogen production by 40-50% (Business Standard, 2022).

The mandate for green hydrogen purchase has been brought back under consideration for the fertiliser and refinery industries, previously shelved because with the increased price of LNG, the cost of green hydrogen became competitive with grey hydrogen (Hydrogeninsight, 2023). According to an assessment by NITI Aayog, the adoption of green hydrogen (produced domestically) has a cumulative mitigation potential of 3.6 GtCO2 by 2050 compared to the use of grey hydrogen (Raj et al., 2022). As a sign of increasing policy support for green hydrogen, at the sub-national level, many Indian states have also started to developing policies for green hydrogen hubs (IEEFA, 2023h).

Carbon markets

India amended its Energy Conservation Act in December 2022, laying the groundwork for a potential domestic carbon market. The Amendment Act includes provisions for the establishment of a carbon market through the introduction of a 'Carbon Credit Trading Scheme' (CCTS) by the Central Government.

The Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE) has released draft rules for a compliance carbon market based on GHG emissions intensity rather than an absolute cap. The draft outlines compliance mechanisms, emissions intensity trajectories, verification processes, and carbon credit issuance, with specific provisions for entities exceeding or failing to meet targets (Enertdata, 2023). The pilot carbon market, which will likely include four heavy industries -petrochemicals, iron and steel, cement and pulp and paper- is anticipated to become operational from April 2025 (Reuters, 2023d). These heavy industries, which previously had energy efficiency targets under the PAT scheme, seems to have had lax targets, resulting in an over-supply and under-pricing of energy saving certificates (ESCerts). The new rules are intending to take cautious approach in setting a transparent and right target.

Carbon capture and storage

India is considering CCUS as an emissions reduction strategy to achieve deep decarbonisation in hard-to-abate sectors and to allow it to continue to use its coal resources (Press Information Bureau, 2022a). Major Indian companies are exploring and implementing CCUS technologies to curb their carbon footprint. This includes partnerships with global technology firms (ONGC, 2024). Several pilot projects and initiatives are underway, supported by both government and private sector investments (Economic Times, 2024c). The commercialisation of CCUS in India by 2050 is essentially unlikely without significant R&D incentives as well as international financial support. However, India has acknowledged, in its LT-LEDS, that CCUS is not a viable technology option for retrofitting existing thermal power plants as it is not cost-effective for India (Government of India, 2022a).

Transport

Transport is responsible for 12% of India’s energy related CO2 emissions (IEA, 2023a). In 2022, India's transport sector consumed 16% of total primary energy but only 1.5% of electricity (IEA, 2023c). The transport sector is dominated by fossil fuels (96% in 2021), mostly oil (93%). 1.5°C compatible pathways for India show a share of electricity in transport reaching 5% by 2030 and 25-76% by 2050 (Climate Analytics, 2024).

Several national programmes, including the National Urban Transport policy and the Smart Cities Mission, have been established to reduce vehicle traffic and increase transport efficiency.

Electric vehicles

By 2030, India aims to increase the share of electric vehicle (EV) sales to 30% in private cars, 70% in commercial vehicles, 40% in buses, and 80% in two and three-wheelers (Clean Energy Ministerial, 2019; The Economic Times, 2021). At COP26, India signed the 100% EV declaration with a focus on two and three-wheeler auto-rickshaws. The government plans to mandate all two-wheelers to be electric by 2026, ahead of the timeline set at COP26 (Pnadya, 2022).

Total annual EV sales reached 1.7 million vehicles in FY2024, of which 55% were two-wheelers and 32% were three-wheelers (JMK Research & Analytics, 2024). This corresponds to 5% and 79% shares of EVs in total sales of two and three-wheelers respectively, showing there is still a lot of work to do to reach the government’s 80% target for two and three-wheelers by 2030. For passenger cars the sales share is much lower, at <0.5%.

Financing and the installation of five million fast chargers are crucial for accelerating the transition to e-mobility. There is a continued focus on expanding the EV charging network, which is expected to create opportunities for small vendors involved in the manufacture, installation, and maintenance of EV charging stations (Indian Express, 2024).

To be compatible with 1.5°C, the share of total EV sales (including two and three wheelers) needs to be 34% by 2030, and 100% by 2040 from current level of around 1% (Climate Action Tracker, 2020).

Back in 2015, the government launched National Electric Bus Programme (NEBP) with the aim to deploy an additional 50,000 new e-buses (UITP, 2022). However, the programme faced obstacles due to the low bankability of electric bus leasing contracts caused by the weak financial condition of Indian State Transport Undertakings (STUs) (IEEFA, 2023d). A recent report by the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas recommends that diesel city buses be prohibited in urban areas as part of a 10-year plan to transition towards cleaner fuel for urban public transport and intercity buses to shift towards all-electric buses with CNG/ LNG as transition fuels (Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, 2023). Budgetary support for urban public electric transport has increased significantly. In the budget of 2024-25, INR1300 crore (USD 155m) has been allocated for the procurement of electric buses, a huge jump from the USD 2.4m in the 2023-24 budget (Climate Group, 2024).

The Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Electric Vehicles in India (FAME) scheme is a key component of India’s EV strategy. It came into effect in April 2019, with financial support of INR 100bn (USD 1.35bn) to provide incentives to purchase electric vehicles and support for establishing the necessary charging infrastructure (Business Today, 2019).

The second phase of FAME ended in March 2024 with a total outlay of INR 115 bn (USD 1.4 bn). The next phase - FAME III - is expected to be introduced soon with a smaller allocation of INR 20 bn (USD 240m) to develop electric mobility infrastructure such as charging networks across the country, although there was no mention of it in the 2024-5 budget (Mint, 2024a).

The scheme aims to support one million electric two-wheelers, 500,000 electric three-wheelers, 55,000 electric cars, and 7,090 electric buses through subsidies. In 2021, this scheme was extended until 2024, as it had made minimal progress in achieving these sales targets (Chaliawala, 2021). A vast network of EV charging stations is needed to support the rapid uptake of EVs. The 2023-24 budget allocated USD 632m for the FAME programme, about an 80% increase from previous budget allocations, but the 2024-5 budget halved it to USD 318m (IEEFA, 2023h; Economic Times, 2024a).

In the 2024-5 budget the government proposed custom duty waivers on 25 critical minerals, which could help lower the cost of EVs and make them more affordable for buyers.

Fuel standards

India strengthened its fuel/emissions standards in April 2020, when it adopted Bharat Stage VI emissions standard for vehicles (the same as Euro VI standards) (DieselNet, 2021). BS VI is applicable to all vehicles with a Gross Vehicle Weight (GVW) of more than 3,500 kg, including commercial trucks, buses and on-road heavy-duty vehicles such as refuse haulers and cement mixers.

The Indian government has advanced different targets and policy frameworks to introduce alternative fuels in the transport sector. Blending of 20% ethanol in petrol is part of such an initiative, for which the target year was slashed to 2025 from the earlier target of 2030 (NITI Aayog, 2021).

Similarly, hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles are seen as a potential solution for long distances for ships and potentially trucks, where electrification is not easily possible (Kukreti, 2021; Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, 2021). Toyota has initiated a pilot project to test its hydrogen fuel cell-powered light vehicle on Indian roads (ET Auto, 2023).

In contrast to these steps forward, in its draft LNG policy 2021 the government is developing plans to use LNG in long-haul heavy-duty trucks and other similar vehicles.

The government has also launched a voluntary vehicle scrappage policy in April 2022 to phase out old vehicles from Indian roads (Garg, 2022). The 2023-24 budget includes provisions for scrapping of Central and State Government vehicles that are over 15 years old, as well as tax incentives for private individuals who exchange their old vehicles by purchasing new ones (Times of India, 2023). However, the new vehicles to be purchased are mostly fossil fuel-driven, as under the policy there is no requirement to replace them with electric vehicles.

Railways and waterways

In July 2020, Indian Railways announced plans to achieve net zero emissions by 2030. It also has a goal of mitigating 60 MtCO2e by 2030 by implementing a range of measures, such as planting trees on unoccupied railway areas, decreasing water usage, and constructing facilities that convert waste into energy (Bloomberg, 2022). In February 2023, it has achieved 100% electrification of its network (International Railway Journal, 2023).

Indian Railways is also planning to increase its use of renewable energy and to install 30 GW of renewable energy capacity by 2030 (Bloomberg, 2022). However, only 245 MW solar capacity installation has been executed on rooftops of various stations and administrative buildings to date.

Indian Railways is looking to introduce hydrogen-fuelled trains on its narrow gauge heritage routes from 2024 and has issued tenders for procuring 35 trains powered by green hydrogen (Railway Technology, 2023; The Economic Times, 2023b). Rollout of green hydrogen driven trains in India will still be subject to the cost competitiveness of the fuel (ET EnergyWorld, 2022b).

The Maritime India Vision 2030 outlines a target for Indian ports to reduce carbon emissions by 30% of per tonne of cargo handled by 2030 (Ministry of Ports Shipping and Waterways, 2021). In November 2022, the National Centre of Excellence for Green Port & Shipping was launched. It is tasked with providing policy and regulatory support to the Ministry of Ports, Shipping and Waterways to develop a regulatory framework and roadmap to foster carbon neutrality and circular economy in India’s shipping sector (Press Information Bureau, 2022b).

Buildings

Per capita building-related emissions in India were nearly four times lower than the G20 average in 2021, reflecting low energy consumption due to lack of access to modern appliances (CTR, 2022). Energy consumption in residential buildings is expected to rise by more than eight times by 2050, hence it is of vital importance for India to develop energy-efficiency strategies focused on the residential sector (Climate Analytics, 2021).

In the last few years, space cooling has become a major source of energy demand from the urban building sector as summer temperatures increase. It has been projected that by 2050, 45% of India's peak electricity demand could come from space cooling (CEEW, 2022). Governmental initiatives like the Energy Conservation Building Code (ECBC), voluntary initiatives on green building guidelines and a push for the adoption of thermal performance standards in building design and construction materials, can help reduce the internal heat load and lower space cooling requirements (BEE, 2021).

The Energy Conservation Act 2022 amendment has expanded the scope for the buildings sector as it now includes offices and residential buildings with a minimum connected load of 100 kW. The amendment of Energy Conservation Act has changed ECBC to “Energy Conservation and Sustainable Building Code”, which specifies norms and standards for energy efficiency, use of renewable energy and other sustainability-related requirements for different types of buildings.

Energy Efficiency Services Limited (EESL), an initiative of the Ministry of Power, is implementing the Buildings Energy Efficiency Programme to retrofit commercial buildings in India with energy efficiency devices. This programme has delivered an estimated cumulative energy savings of 790 GWh since 2009 with avoided peak demand of 75.64 MW, cumulative emissions reduction of 0.57 MtCO2 and an estimated cumulative monetary savings of INR 6 bn (USD 72 mn) in electricity bills since its inception in 2009 (EESL, 2022).

Agriculture

Agriculture is the second highest emitting sector in India after energy, contributing around 14% of total emissions (excluding LULUCF) (Gütschow & Pflüger, 2023). Given that well over half of India’s population generates an income from agriculture, this sector is particularly important. It is also intricately linked to the power sector, as electricity is used for water pumping in modern irrigation. The heavily-subsidised power supply to agriculture has contributed to the use of inefficient pumps and a resulting excessive use of both water and power (Sagebiel et al., 2015).

Demand Side Management (DSM) has been recognised as one of the major interventions to achieve energy efficiency in India’s agricultural sector (MoEFCC, 2021). In 2023, the Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE) launched Agricultural Demand Side Management (AgDSM) to reduce overall power consumption, improve efficiencies of ground water extraction, and reduce the subsidy burden on power utilities (BEE, 2023). The PM-KUSUM (Pradhan Mantri Kisan Urja Suraksha evam Utthan Mahabhiyan) scheme aims at setting up 10 GW of decentralised grid-connected solar capacity in barren land, along with 17.5 million solar pumps to reduce the use of diesel in agricultural activity (MNRE, 2020). The government has extended PM-KUSUM scheme until March 2026, as its implementation was significantly affected by the pandemic (The Economic Times, 2023d).

India is the second largest emitter of nitrous oxide (N2O) after China, contributing around 11% of global nitrous oxide in 2020, mostly due to the use of nitrogen-based fertilisers. The government has implemented measures to reduce N2O emissions associated with fertiliser (urea) use and has programmes in place to assist farmers in reducing emissions and building resiliency (Department of Fertilizers, 2022).

Forestry

In 2015 in its first NDC, India set a target of 2.5-3 GtCO2e of an additional carbon sink by 2030, reconfirmed in its 2022 update. To achieve that target, a comprehensive forest policy is essential. Between 2001 and 2023 the net carbon sink from Indian forests accounted for -88.1 MtCO2e/year (Global Forest Watch, 2024). In 2022, in response to a question in the Indian parliament, the minister claimed that India had already achieved 1.97 GtCO2e of additional carbon sink compared to 2005, which would put it on track to achieving its target (Government of India, 2022c). However, it is unclear whether this is an additional carbon sink and whether it is contributing to India’s NDC target.

As of 2021, forest and tree cover accounts for 24.6% of India’s land mass compared to 21% in 2005, against a national target of 33% forest cover as proposed in 1952 National Forest Policy. Between 2010 and 2023, India lost around 134 kha of natural forest, equivalent to emissions of 81.9 MtCO2e. Mining, road construction and irrigation all contribute to forest cover loss (CNBCTV18, 2022).

On August 2023, the Forest (Conservation) Amendment Bill 2023 was passed by the parliament (PIB India, 2023b). This amendment of the 1980 Forest Conservation Act (FCA) has acknowledged the role of forest carbon sinks in achieving the net zero target by 2070, but it has been criticised by various quarters, including government opposition members, former officials, and environmentalists (ETEnergyWorld, 2023). One issue is the absence of a legal definition of forests in India, based on which the amendment proposes the removal of FCA protections for private forested land and unrecorded forested parcels.

The amendment also exempts the construction of 'linear projects' within 100 km of disputed national borders from the Forest Conservation Act (FCA). This exemption is particularly significant due to the vulnerability of the Himalayan region in the north and northeast of the country, which is part of a global biodiversity hotspot (Third Pole, 2023). It carries important implications for the environmental resilience of these areas. The bill also eliminates pre-clearance checks, such as seeking consent from indigenous inhabitants for affected lands, and opens up forests for activities like eco-tourism zones and zoos, raising concerns about potential ecological impact (Third Pole, 2023).

In 2022, before this amendment came into place, India adopted the Forest Conservation Rules to implement the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980. However, these new rules will permit private developers to clear forests without obtaining prior permission from the forest dwellers (Down To Earth, 2023).

The National Mission for a Green India was launched in 2014 to protect, restore and enhance India’s forest cover as a response to climate change. Under this mission, the aim is to convert 10 Mha of forest and non-forest land to increase the forest cover and to improve the quality of existing forest. (Ministry of Environment, 2022).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter