Policies & action

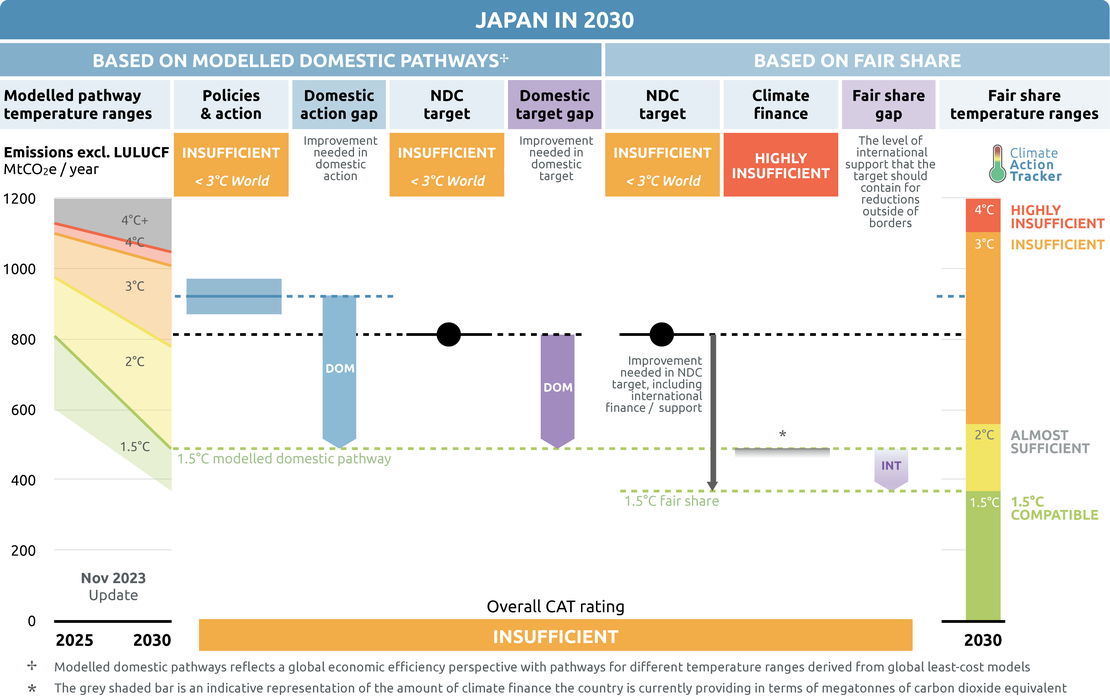

The CAT rates Japan’s policies and action against modelled domestic pathways as “Insufficient”. The “Insufficient” rating indicates that Japan’s NDC target against modelled domestic pathways needs substantial improvements to be consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C. If all countries were to follow Japan’s approach, warming would reach over 2°C and up to 3°C.

Further information on how the CAT rates countries (against modelled domestic pathways and fair share) can be found here.

Policy overview

The CAT estimates that Japan’s implemented policies will lead to emission levels of 31% to 38% below 2013 levels in 2030, falling short of its latest NDC target of a 42% reduction below 2013 levels, both excluding LULUCF. Without additional measures, Japan will likely miss its NDC target, as well as it 60% reduction below 2013 levels target , the only one we estimate to be 1.5°C-compatible.

In February 2023, the government adopted the Green Transformation (GX) Basic Policy, a set of initiatives that aims to generate approximately JPY150 tn (approx. USD 1 tn) of public-private investment over the next 10 years (METI, 2023e). This new strategy seeks to ramp up decarbonisation efforts in key industrial sectors through the GX League, a voluntary group of industries who individually set their own decarbonisation targets to be in line with the national reduction targets and participate in an emissions trading scheme to achieve them (i.e. 46% emissions reduction in 2030 below 2013 levels and achieving carbon neutrality by 2050) (CAS, 2022; METI, 2022a). As of January 2023, 679 companies which collectively account for 40% of CO2 emissions (including indirect emissions from electricity use in households) have joined the group (GX league, 2023)

However, the GX Basic Policy places more emphasis on economic growth and energy security, rather than prioritising ambitious decarbonisation efforts. The new strategy indeed does not provide any emissions reduction targets for 2030 or 2050. While it finally lays out a blueprint for the introduction of a carbon pricing scheme, there are concerns that the system envisioned by the government will not be effective in reducing Japan’s emissions. It remains unclear whether the emissions trading scheme currently being considered for 2026 will still be based on voluntary participation (InfluenceMap, 2023; METI, 2023d). On top of that, the carbon levy, which will only be implemented in 2028, is expected to be set a low level (Renewable Energy Institute, 2023b).

There are also concerns that the GX Basic Policy will keep Japan wedded to coal, as it puts a strong emphasis on the need to develop CCS technologies, and ammonia and hydrogen co-firing, as tools to to curb emissions in coal fired power plants.

Japan remains the only G7 country planning to build new coal-fired power plants, a policy inconsistent with the government’s climate engagements. Japan must commit to a full coal phase-out and further accelerate its low-carbon transition, particularly as a member of the G7 group which committed in June 2022 to achieve “fully or predominantly” decarbonised electricity by 2035 (G7, 2022). Japan could reduce its dependence on fossil fuel and bolster its energy security by scaling up renewable energy (Shirashi et al, 2023).

In a significant policy shift, Japan moved to re-start its currently idled nuclear reactors and plans to build new generation reactors, as part of the GX Basic Policy. Despite this reversal, many regulatory and political hurdles remain, and it is unlikely that nuclear power will help Japan meet its 2030 objectives.

One policy that may contribute to significant additional reductions, though its effects would only take place in the long-term, is the revision of building standards by which all new houses and buildings will need to comply with upgraded energy efficiency standards from 2025 (MLIT, 2022). This is a significant step forward as the emissions from the buildings sector increased by 34% in 2020 above 1990 levels while Japan currently aims to achieve 28% emissions reduction in 2030 below 1990 levels. (GIO, 2022; Government of Japan, 2021b).

To also support decarbonising existing houses and buildings, several measures have been introduced including financial support for house renovations to improve energy efficiency as well as promoting the use of renewable energy in buildings (MLIT, 2022). Japan aims to achieve on stock average net-zero energy consumption for newly constructed buildings (ZEBs) and houses (ZEHs) by 2030 as well as all buildings and houses by 2050 (MLIT, 2022). Additionally, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government has mandated majority of new buildings and houses to install solar panels from 2025 (The Japan Times, 2022b)

The table below illustrates the fuel mix in the power sector in 2022, and the different assumptions for our projections, in comparison to the IEA World Energy Outlook (WEO) 202(IEA, 2023) (See Assumptions tab for details).

| Shares of different fuels in electricity mix (%) |

|---|

| 2022 | 2030 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fuel | Historical | Low emissions case | High emissions case | WEO2023 | First NDC | Updated NDC |

|---|

| Nuclear | 6 | 20 | 11 | 20 | 20–22 | 20–22 |

| RE | 21 | 37 | 30 | 37 | 22–24 | 36–38 |

| Coal | 31 | 19 | 27 | 19 | 26 | 19 |

| Oil | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Gas | 34 | 20 | 27 | 20 | 27 | 20 |

| Hydrogen and ammonia | – | – | – | 1 | – | 1 |

Sectoral pledges

In Glasgow, four sectoral initiatives were launched to accelerate climate action on methane, the coal exit, 100% EVs and forests. At most, these initiatives may close the 2030 emissions gap by around 9 % - or 2.2 GtCO2e, though assessing what is new and what is already covered by existing NDC targets is challenging.

For methane, signatories agreed to cut emissions in all sectors by 30% globally over the next decade. The coal exit initiative seeks to transition away from unabated coal power by the 2030s or 2040s and to cease building new coal plants. Signatories of the COP26 declaration on 100% zero emission vehicles agreed that 100% of new car and van sales in 2040 should be electric vehicles, 2035 for leading markets, and on forests, leaders agreed “to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030”.

NDCs should be updated to include these sectoral initiatives, if they’re not already covered by existing NDC targets. As with all targets, implementation of the necessary policies and measures is critical to ensuring that these sectoral objectives are actually achieved.

| JAPAN | Signed? | Included in NDC? | Taking action to achieve? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methane | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Coal exit | No | No | Not applicable (non-members) |

| Electric vehicles | No | No | Not applicable (non-members) |

| Forestry | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Beyond oil and gas | No | Not applicable | Not applicable (non-members) |

- Coal exit: Japan has not adopted the coal exit and plans to use coal to supply 19% of electricity in 2030 according to its latest NDC updated in October 2021. This stands in stark contrast to the 2022 G7 commitment to achieve “fully or predominantly” decarbonised electricity by 2035 (G7, 2022).

- Zero emission vehicles: Japan has not adopted the zero emission vehicles target and instead successfully pushed to remove any concrete target from the G7 commitment in 2022 (Yamazaki & Abnett, 2022). Japan currently aims for 100 % new sale of “electrified vehicles” which includes non-plug-in hybrids (HVs) and plug-in hybrid vehicles (PHV) by, latest, 2035.

Energy supply

With its latest Basic Energy Plan, Japan currently aims to supply electricity from 36–38% renewable electricity, 20–22% nuclear, 20% gas and 19% coal in 2030 (METI, 2021a). While the indicated share of decarbonised electricity is roughly in line with our 1.5oC benchmark (though at the lowest end), keeping 19% of coal-fired power generation is completely inconsistent with the virtually full coal phase-out needed by 2030 (Climate Action Tracker, 2021; IEA, 2021). Additional measures are certainly necessary also to achieve fully or predominantly decarbonising electricity by 2035, a goal Japan committed as a member of G7 in April 2023(G7, 2023).

Nuclear Power

Nuclear power’s role in Japanese future energy mix remains uncertain. As of 10 October 2023, 25 reactors in 15 nuclear power plants have applied for a restart (plus two in construction applied for operation); 17 reactors with a total of 17 GW have passed the safety examination and have been approved for restart (under the condition that the plans for the construction work are approved by neighbouring local governments and the required safety measures are properly installed), of which 12 are currently in operation(JAIF, 2023).

In a significant policy shift, Prime Minister Kishida recently announced that Japan will move to re-start the currently idled rectors, and build new generation reactors, as part of the GX Basic Policy (Asahi Shimbun, 2023b; METI, 2023d). The government also plans to allow nuclear reactors to operate beyond their 60-year limit. Under the new system, the time during which reactors are offline due to inspections, construction or legal actions, would be excluded from their total lifespan, therefore allowing them to be operated beyond the current limit (Nikkei Asia, 2023a). The related amendment bills were recently approved by the Cabinet and are currently being deliberated in parliament.

Despite this reversal, many hurdles remain and it is likely, that nuclear power plant operations will continue to be disrupted by unplanned inspections as well as legal action to stop them. There have already been a few district court rulings to halt the operation of the restarted reactors (National network of legal teams for nuclear phase-out, 2023; Nikkei Asia, 2022a; The Japan Times, 2023). ,

While the Japanese public is increasingly in favour of expanding nuclear energy in the light of energy prices (Asahi Shimbun, 2023c), strong opposition remains, particularly among local governments hosting nuclear plants. To re-start a reactor or build a new plant, power companies must obtain the approval of local authorities, including all municipalities located within 30km2 of the facilities, which can be quite lengthy (Nikkei, 2022a). As a result, nuclear power will not be able to help Japan meet its 2030 targets.

We estimate, based on these developments, that the nuclear power share will range between 11% and 20% in 2030 (see Table 1, and also Assumptions tab). Our upper end estimate reaches the government target.

Coal

Japan is finally starting to officially shift, albeit gradually, away from developing coal power, both domestically and overseas. The 19% coal-fired power generation share in 2030 is, even though far from being 1.5oC-consistent, a considerable step forward from the previous NDC target.

However, the government has no intention of fully phasing out coal and is instead focusing on promoting so-called “clean” coal technologies (METI, 2023f). It has officially included thermal power with CCS as well as ammonia and hydrogen — most of which are currently produced from fossil fuels — as non-fossil energy sources to promote their use as decarbonised fuel (METI, 2022b). The GX Basic Policy also puts a strong emphasis on the need to develop ammonia and hydrogen co-firing in thermal power plants (METI, 2023d). However, a recent report shows that ammonia-coal co-firing power would not be an economically viable option compared to renewable electricity (further description below, under Hydrogen and ammonia) (BloombergNEF, 2022; Kiko Network, 2021).

CCS technologies are playing an increasing role in Japan’s decarbonisation strategy. Under a long-term roadmap for CCS, Japan currently aims to store 120-240 million tonnes of CO2 a year in 2050. To achieve this target, METI unveiled plans to raise its annual CO2 storage capacity by 6-12 million tones every year from 2030 (Reuters, 2023a).

The ministry has identified 11 potential storage sites in Japan with an estimated total capacity of 16 billion tones (METI, 2023c). The government expects CCS to play a large role in achieving carbon neutrality by 2050. However, CCS technologies have yet to commercially viable and are not yet proven at scale despite large public subsidies for research and development. On top of that, there is no suitable location for CO2 storage in Japan nor oil fields for CO2 enhanced oil recovery, thus forcing the government to consider exporting large amount of CO2 to other countries (Renewable Energy Institute, 2022a). At a time where an increasing number of governments are committing to net zero emissions, Japan’s strategy risk drawing international criticism, while further deepening its energy reliance on other countries.

These polices are widely seen as a strategy to prolong the life of fossil-based electricity, in particular coal (JBC, 2022; Obayashi, 2022). The Japanese government indeed relies on CCS both to decarbonise thermal power generation and to supply hydrogen from fossil fuel sources (Renewable Energy Institute, 2022a).

While the government also plans to increase coal-fired power plant efficiency standards from 41% to 43% (METI, 2021d), it is important to note that such efficiency standards should not distract from the need to phase out coal-fired power by 2030(Boehm et al., 2022).

Japan has also been a major funder of coal-fired power plants overseas, alongside China and South Korea (EndCoal, 2020). Japan has been the G20’s largest supporter of international fossil fuel projects through export credit agencies (DeAngelis & Tucker, 2020). Faced with mounting international pressure, Japan agreed at the 2021 G7 summit to end new public financing for unabated coal projects overseas by the end of 2021 (G7, 2021), and, at the 2022 Summit, further committed to end such financing also for other fossil projects overseas by the end of 2022 (G7, 2022; The Japan Times, 2022a). However, despite these commitments, Japan is still financing fossil gas projects overseas (Fossil Free Japan, 2023; Oil Change International, 2023).

While the private sector also shows signs of change, the actual divestment speed remains very slow(Reuter, 2023; Trencher et al., 2020). For example, despite the announcement of gradual divestments, Japan’s largest banks — Mizuho, MUFG and SMBC Group — still remain the top three lenders for global coal projects, financing a total of USD 61bn between January 2019 and November 2021 (Urgewald, 2022).

Renewables

Renewable electricity generation has grown steadily in recent years. The share of renewable energy in total electricity generation in Japan has increased from 10% in 2010 to 23% in 2020. While there are other supplementary measures (such as subsidies for installing renewables in buildings described below, under Buildings), the 2012 Renewable Energy Act remains the main policy to achieve Japan’s renewable electricity share target of 36-38% by 2030 under its latest NDC. It institutes a feed-in tariff (FIT), which was partially shifted to a Feed in Premium (FIP) for large-scale projects in April 2022, and general funding for distribution networks.

The FIT/FIP has provided very favourable rates, particularly for solar PV, which led to a large increase in PV installations; by April 2022, 64 GW of solar PV was installed and operational as a result of the FIT scheme (another 13 GW was installed but not yet operational) producing 8% of electricity, against the targeted deployment of 104–118 GW (14–16% of electricity) by 2030 (METI, 2022e). It should be noted that 64 GW of solar PV was Japan’s previous target for solar power. However, no significant growth has yet been observed for other renewables such as wind which only produced 0.9% of electricity in 2020 (METI, 2022e). Among the large emitters, Japan has one of the highest installed solar PV capacity per capita, but lags behind other countries in terms of wind power(Renewable Energy Institute, 2022c). As a measure to accelerate its development, a new law entered into force to facilitate the use of maritime areas for offshore wind power generation (METI, 2019a).

The government has an aspirational target to develop 10GW of offshore wind by 2030 and 30-45 GW by 2040. While we do not consider this target in our emissions projections as it is not included in Japan’s NDC, we estimate it could lead to an additional renewable electricity generation of 26 TWh/year or 2.5% of total electricity generation in 2030, assuming a 30% capacity factor. However, it should be noted that 10 GW for 2030 target is for approved projects under development rather than operational capacity. The government is targeting 5.7 GW of offshore wind operational capacity by 2030 (InfraBiz, 2021).

The first auction for three large-scale offshore wind projects (1.7 GW in total) was won by Mitsubishi Corporation-led business consortia at JPY 11.99 ($0.1)/kWh as the tariff priced. This was far below the ceiling price set by the government at JPY 29 /kWh (METI, 2022e). However, there were doubts that Mitsubishi’s pricing model could be sustained under the FIT system, a condition on the bid that requires the energy to be sold at a fixed price. Additionally, all the locations won by the consortia had late operational starts, with the earliest only beginning in September 2028 (Xtech Nikkei, 2022a). The outcome of the first round and the response from the industry prompted METI to suspend the offshore wind auction and revise its scoring system (Nikkei, 2022c).

In December 2022, the government resumed the auction under a new point system that values bid price and “non-price” factors equally. METI is now prioritising feasible projects with earlier operational starts(Xtech Nikkei, 2022b). The ministry has also set a 1 GW limit on bids that a consortium can win when multiple areas are being auctioned in one round (World-Energy, 2022). The results of the second round of auction will be announced in March 2023 (Nikkei Asia, 2023b).

Hydrogen and ammonia

Japan shows a strong commitment to develop hydrogen as a major decarbonised fuel. In April 2023, METI unveiled plans to revised Japan’s Basic Hydrogen Strategy, with a view to boost annual supply to 12 million tonnes by 2040 (Asahi Shimbun, 2023a). The government is considering introducing a JPY 15tn investment plan over the next 15 years and is also seeking to develop a hydrogen value chain via Australia, the Middle East and Asia. (METI, 2023h).

The initial plan released by METI highlights the need to position Japan as a leader in “clean hydrogen”. However, that term refers to both blue and green hydrogen (METI, 2023h). Due to high costs involved, METI has been relatively colour blind in its investments, exploring grey and blue hydrogen more so than green hydrogen development (METI, 2017, 2019b; Renewable Energy Institute, 2022b).

Two of the world’s largest low-carbon hydrogen production facilities are located in Japan in Fukushima (10 MW) and Yamanashi (16MW) (METI, 2022d). Australia’s national hydrogen strategy also identifies Japan as a potential major importer of Australian hydrogen (COAG Energy Council, 2019). An Australian-Japanese coal-to-hydrogen pilot project transported liquefied hydrogen for the first time in the world on February 2022 and aims for commercialisation by 2029 (METI, 2022d). It is important to note that without the successful development and deployment of CCS, which is not yet available at scale and expected to remain costly in the future, such so-called “brown” hydrogen, produced by burning coal, would not contribute to reducing emissions (Gunia, 2022).

The Green Growth Strategy also highlights the potential role of ammonia in reducing GHG emissions (METI, 2021b). The document indicates, for example, the possibility of using a 20% ammonia blend with coal to reduce emissions in thermal power plants. JERA, Japan’s largest power generation company, has already set up a plan to create a pilot programme with the intention of using this blended fuel by 2035 (JERA, 2020).

The GX Basic Policy also promotes the development of ammonia and hydrogen co-firing in thermal power plants (METI, 2023d). However, hydrogen and ammonia technologies are less developed, potentially more costly, and their emissions reduction potential is questionable (Gunia, 2022; Stocks et al., 2022), compared to commercially available low-carbon technologies that could be deployed at scale before 2030 and help Japan get on the right trajectory to achieve its 2050 net zero goal.

Industry

CO2 emissions from the industry sector (including indirect emissions from electricity use as well as emissions from industrial processes) accounted for 35% of Japan’s total energy-related CO2 emissions in 2021 (GIO, 2023).

Within the industry sector, the iron and steel, chemical and cement industries are the three largest emitters, respectively emitting 39%, 15% and 8% of industrial emissions in 2021. Emissions in the sector have reduced by 20% below 2013 levels (GIO, 2023). A 2022 progress report shows that the industry CO2 emissions from the member companies of Keidanren, the most influential business association in Japan, including indirect emissions from electricity use in FY2021, was 17.7% lower than in 2013. However, the majority of the emissions reduction is attributable to the changes in industrial activity levels induced by the COVID-19 pandemic (Keidanren, 2023). Following Japan’s economic recovery, emissions from electric use rebounded in FY2021 but remained lower than in FY2019, as the effects of the pandemic continued to linger in key industrial sectors.

The main GHG emissions reduction effort in the industry is Keidanren’s Commitment to a Low-Carbon Society (Keidanren, 2013), a voluntary action plan which has monitoring obligations under the Plan for Global Warming Countermeasures (MOEJ, 2016b). Keidanren has since launched its Challenge Zero Initiative, in collaboration with the Japanese government, inviting companies to submit strategies to decarbonise their activities; a number of actors have already disclosed measures to be implemented, including in the steel and chemical industries (Keidanren, 2020).

Among the industrial sectors that pledged to 2050 net zero goal is the iron and steel sector. The Japanese Iron and Steel Federation (JISF) announced in 2021 that it would aim to reach net zero CO2 emissions by 2050 (JISF, 2021).JISF aims to cut emissions in the iron and steel industry, which is Japan’s largest CO2 emitters, by 30% by 2030 compared to 2013 levels. Its stance on climate change seemed to have changed considerably since 2018, when it published a long-term decarbonisation vision that drew global emissions pathways reaching zero in 2100 to achieve the 2°C temperature goal (JISF, 2018). In 2021, CO2 emissions from JISF members were 16% below 2013 levels. However the majority of this reduction can be attributed due to “production fluctuations”, namely decrease in production, rather than the adoption of sector specific mitigation measures (JISF, 2023).

Nippon steel, the largest steel-producing company in Japan and the fourth largest in the world, also released a decarbonisation road map in 2021. The company aims to develop and commercialise large electric arc furnaces by 2030 and expand the use of hydrogen in the sector (Argus Media, 2021; Nikkei, 2021). JFE Steel, Japan’s second largest steelmaker, has also announced plans to replace its blast furnace located in Okayama Prefecture with an electric arc furnace by 2027 (Nikkei, 2022b). However, the deployment of electric furnaces remain slow in Japan (Global Energy Monitor, 2023).

Other key industry associations have also unveiled new decarbonisation strategy. In 2022, the Japan Cement Association announced that it will aim to cut emissions in the sector by 15% by 2030 compared to 2013 levels (METI, 2022c).

The GX Basic Policy set roadmaps covering key sectors of the Japanese economy including the chemical, the iron and steel and the cement industries. These roadmaps introduced several targets, although many were already announced by industry associations in 2022 (METI, 2023d). One new target includes the increase of green steel supply to 10 million tonnes by 2030, although the exact definition of green steel remains unclear. It should however be noted that 10 million tonnes only represented around 1% of Japan annual steel production in 2021(World Steel Association, 2022).

Carbon pricing

In December 2022, the Japanese government unveiled a blueprint for the introduction of a carbon pricing scheme, as part of the GX Basic Policy (METI, 2023e). This system will be based on two pillars:

- A carbon levy targeting power, gas, and oil companies, which will be introduced in 2028 and reviewed upward annually.

- An emissions trading scheme (ETS), which is being implemented in phases.

The ETS was first launched in April 2023 but only among the GX league companies. The scheme was set up on a voluntary basis with GX League companies allowed to set their own emissions caps. Based on the results of this trial, the government aims to expand the scheme to cover more companies in 2026. The scope of the target companies and the exact features of the ETS remain to be determined (MoEJ, 2023).

As for the final phase, the government plans to introduce the ETS “fully” in 2033, with a shift to a mandatory scheme that will include trading based on allowances auction. However, it will exclusively target the power sector (Nikkei, 2023a), and no other sectors of the Japanese economy. The government plans to use the revenues generated by the carbon pricing scheme to issue “GX Transition bonds” through which it hopes to raise JPY 20 tn (METI, 2023d).

Details on the overall system have yet to be announced, but the carbon levy is expected to be set at around JPY 1,500 /t-CO2, which is seen at too low to be effective (Climate Integrate, 2023). Research shows that with a carbon price set at JPY 3,300/t-CO2, new solar PV energy and onshore wind power generation would outcompete coal-fired power generation (Carbon Tracker, 2022).

This blueprint constitutes a step in the right direction, as discussions on carbon pricing in Japan have stalled for many years. However, it remains unclear whether the emissions trading scheme being considered for 2026 will still be based on voluntary participation (InfluenceMap, 2023). Additionally, the timeline and the carbon levy currently being considered by the government means the scheme will not help Japan meet its 2030 target. On top of that, the government is considering investing the revenues generated from the “GX Transition bonds” partly in the development of grey hydrogen and grey ammonia, rather than renewable energy (Renewable Energy Institute, 2023a).

Transport

CO2 emissions from the transport sector accounted for 18% of Japan’s total energy-related CO2 emissions in 2021 (GIO, 2023).

Regarding vehicle decarbonisation, the government announced a target of reaching 100% of “electrified vehicles” – a category that includes non-plug-in hybrids (HVs) and plug-in hybrid vehicles (PHV) – in the sale of passenger vehicles by, latest, 2035 (METI, 2020), replacing the previous target of reaching 50-70% of ‘new generation’ vehicles (including hybrids, plug-in hybrids, battery electric vehicles, fuel cell electric vehicles, as well as ‘clean diesel’ vehicles and gas-powered vehicles) in the share of sales by 2030 (METI, 2018b).

This policy, which still allows for non-plug-in HVs to be sold in 2035, could be further strengthened to become consistent with the 1.5°C-compatible benchmark to phase out all fossil-fuel passenger (ICE) cars from new sales by 2035 (Kuramochi et al., 2018). Japan’s commitment to transition away from ICE vehicles could further impact the global car manufacturing sector. Given the importance of the industry at both the national and international level, it could define a globally ambitious and innovative strategy favouring the development and deployment of zero-emission vehicles.

Additional pressure from investors has also started to impact car manufacturers’ strategies; Toyota has for example, recently announced the launch of 10 new EV models by 2026(Nikkei Asia, 2023c). Honda has also unveiled a new EV strategy, with plans to release 30 EV models by 2030(Nikkei, 2023b).However, despite these announcements, Japanese car manufacturers are still falling behind in the global race towards EVs. In 2020, Japanese cars only accounted for less than 5% of EVs sold worldwide(The New York Times, 2021).

Despite the mounting pressure to speed up electrification of the transport industry, Japanese carmakers are moving cautiously compared to their counterparts. Many in the industry remain wary about making the shift to electric vehicles and would rather keep investing in internal combustion engine manufacture. For example, Toyota has recently announced that, while it will continue to ramp up its EV production capacity, hybrid vehicles will remain an important pillar of the company’s strategy(Reuters, 2023b).

The GX Basic Policy did not set a more ambitious target for EVs. However, as part of the strategy, Japan plans to install 150,000 EV charging stations and 1000 hydrogen stations by 2030 (METI, 2023d), a positive development considering Japan is also lagging behind on EV infrastructure.

Buildings

CO2 emissions (including indirect emissions from electricity use) from the commercial and residential building sectors together accounted for 32% of Japan’s total energy-related CO2 emissions in 2021 (GIO, 2023).

Compared to 1990, the emissions in these two sectors have increased by 42% and 19%, respectively (GIO, 2023). Although these significant increases are partially attributable to the increased electricity CO2-intensity post-Fukushima, there’s an urgent need for strengthened action on the demand side in the buildings sector.

An important recent development is the revised Building Energy Conservation Act, which entered into force in June 2022 mandating all new houses and buildings from 2025 to comply with upgraded energy efficiency standards. This is a significant step forward from the current regulation which is only applicable to buildings larger than 300 m2.

To also support decarbonising existing houses and buildings, several measures have been introduced, including financial support for household renovations to improve energy efficiency, as well as promoting the use of renewable energy in buildings.

Japan aims to achieve on stock average net-zero energy consumption for newly constructed buildings (ZEBs) and houses (ZEHs) by 2030 as well as all buildings and houses by 2050 (MLIT, 2022). This is a step change as in 2020, only 0.42% of newly built buildings was ZEBs, and 24% of newly built houses was ZEHs (METI, 2022f; METI & MOEJ, 2022). For comparison: the EU requires all new buildings to be near zero energy as of 2022.

The GX Basic Policy sets the objective to invest at least JPY 14 tn in the building sector over the next ten years (METI, 2023d).

In December 2022, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government also adopted the “Renewable Energy Installation Standards”, a regulation requiring construction companies to install rooftop solar panels on new buildings (including residential properties) of up to 2,000 m2, from 2025 (The Japan Times, 2022c). This new policy exclusively targets companies whose building projects total at least 20,000 m2 or more per year, so around 50 companies.

The Tokyo Metropolitan Government will set up thresholds per district, ranging from 30%, to 70 -85% of new buildings. The city will also provide subsidies to encourage the installation of solar panels on existing buildings, which are currently excluded from the regulation (Tokyo Metropolitan Government, 2022). The “Renewable Energy Installation Standards“ is expected to be impactful, as half of existing buildings will be replaced with new ones before 2050.

F-gases

F-gas emissions increased by more than 50% between 2013 and 2021 (GIO, 2023). Japan aims to reduce these emissions by 44% below 2013 levels by 2030, through enhanced management of in-use stock and regulating consumption levels (METI & MOEJ, 2021a).

On the management of in-use stock, Japan aims to increase the recovery rate of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) from end-of-use refrigeration and air conditioning equipment up to 50% by 2020 and 70% by 2030. The Act on Rational Use and Proper Management of Fluorocarbons (“F-gas Act”), last amended in 2013, addresses this, but the recovery rate has stagnated: in 2019 the recovery rate of refrigerants was only 38% (METI & MOEJ, 2021a). While the F-gas Act was further amended by introducing several penalty and obligatory measures to increase the F-gas recovery rate, it was only increased to 41% in 2020, missing the 50% recovery target (METI & MOEJ, 2021b). The recovery rate even dropped to 40% in 2021 (MoEJ, 2022).

To meet the HFC reduction target under the NDC and the targets under the Kigali Amendment of the Montreal Protocol, the Ozone Layer Protection Act was amended in 2018 and measures took effect in April 2019.

The amendment sets a ceiling on the production and consumption of HFCs, establishes guidelines to allocate production quota per producer as well as regulates exports and imports (METI, 2018a). The consumption levels are projected to be below the Kigali cap at least until 2029, when the Kigali cap lowers significantly. Since there is some time lag between consumption and emissions, we assume that the amended Ozone Layer Protection Act will not affect HFC emission levels up to 2030 (METI, 2018a).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter