Pledges And Targets

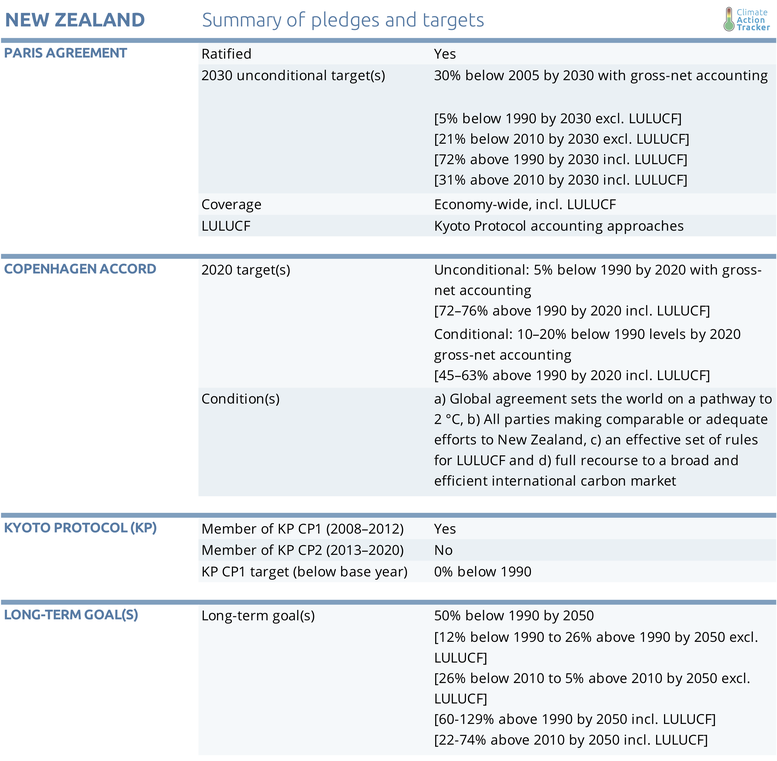

Summary table

Paris Agreement targets

New Zealand ratified the Paris Agreement on 4 October 2016; its NDC contains a target of a 30% reduction from 2005 levels by 2030 (New Zealand Government, 2016c). New Zealand intends to use international market mechanisms, cooperative approaches and carbon markets to meet its target. We estimate that the emission level excluding LULUCF targeted by the NDC is 62 MtCO2e in 2030.

New Zealand’s LULUCF accounting approach remains unclear: the statement that the 30% reduction below 2005 levels is equivalent to a reduction of 11% from 1990 levels confirmed in the Third Biennial Report (Ministry for the Environment, 2017b), suggests that New Zealand is planning to exclude LULUCF emissions in the base year but account for them in the target year, which is known as a “gross-net” approach (see Assumptions section). The use of this approach raises many questions in terms of the environmental integrity of the target (Rocha et al., 2015). However, the accounting rules that will be used under the Paris Agreement have not yet been defined and therefore the legal basis upon which New Zealand is seeking to rely upon such accounting rules is unclear. For indicative purposes we therefore show also the emissions levels that the NDC target would represent if using a net-net approach (43 MtCO2e in 2030).

Further uncertainty around the emissions levels that New Zealand could have in 2030 without missing its NDC target is added by the New Zealand Government’s statement that it is planning to meet its NDC target through a combination of domestic emissions reductions, participation in international markets, and removal of carbon dioxide by forests (Ministry for the Environment, 2017b). We have further analysed the implications of New Zealand seeking to continue to apply a Kyoto-type accounting system as described in the NDC (New Zealand Government, 2015), despite having not signed up to the second commitment period (CP2), and to carry over surplus units from CP2 to the post-2020 period, even though their ability to do so in the Paris Agreement has been neither verified nor prohibited.

Using the information about Kyoto Protocol forestry activity credits in the CP2 provided in the latest net position update, we updated our estimates and found that if New Zealand were able to apply its preferred accounting rules, its nominal 30% reduction from 2005 levels by 2030 pledge could, in reality, enable an increase in GHG emissions excluding LULUCF to 79–81 MtCO2e, or 3-5% below a 2005 levels by 2030. More clarity around the intentions of the government around the surplus units in the post-2020 period would be needed for an updated estimate of the impacts of the suggested approaches in the NDC target. For a more detailed description of the methodology and assumptions used in previous reports to estimate the potential impacts of a Kyoto-type accounting system for New Zealand’s NDC target see our 2015 country report.

2020 Pledge and Kyoto target

New Zealand's Kyoto Protocol target for the first commitment period (CP1) (2008–2012) was to return its GHG emissions excl. LULUCF to 1990 levels (QELRO of 100% of 1990 emissions).

Under the Kyoto Protocol accounting rules applicable to New Zealand in CP1, certain land-use change and forestry activities provided credits that were added to allowed GHG emissions, excl. LULUCF, during this commitment period. In CP1, these activities resulted in extra emission allowances for New Zealand of, on average, 14 MtCO2e per year (equivalent to about 23% of base year emissions in 1990). As a consequence of its large volume of LULUCF credits, New Zealand had a substantial surplus of unused emission units at the end of CP1. In addition to LULUCF credits, New Zealand used a large amount of Emissions reduction Units (ERUs) of unclear environmental integrity to meet a significant part of its CP1 target (Sustainability Council of New Zealand, 2014).

As explained below, New Zealand proposes to use these surplus emission allowances from CP1, which are derived in part from Kyoto LULUCF credits and acquired emission units from other countries, to meet its 2020 reduction target under the Convention.

In 2013 New Zealand put forward an unconditional pledge to reduce GHG emissions excluding LULUCF by 5% below 1990 levels by 2020. This pledge is complemented by an earlier conditional pledge from 2009 to reduce emissions 10–20% below 1990 levels by 2020 (Government of New Zealand, 2013). The government provided further details, including its plans to apply Kyoto-type accounting rules governing the second commitment period (2013–2020).

New Zealand’s unusual decision to adhere to the Kyoto rules and subsequently ratifying the Doha amendments without signing up to the CP2 raises a number of legal issues, as the Protocol provides certain benefits only to Parties that have emission reduction commitments for CP2.1 If New Zealand were able to apply its preferred accounting rules, and use these units to offset its fossil fuel and industrial emissions, we calculate that its nominal 5% reduction from 1990 levels by 2020 pledge (around 63 MtCO2e in 2020) could, in reality, enable an increase in GHG emissions excluding LULUCF to 95–108 MtCO2e, or 44–64% above 1990 levels by 2020.

The latest net position update produced in April 2018 confirmed that New Zealand is projected to meet its unconditional target to reduce emissions to 5% below 1990 levels by 2020 with a surplus of 92.4 million units, by making use of 31.3 million available units from CP1 (out of a total surplus of 123.7 million units) to meet its 2020 target, where one unit represents one tonne of greenhouse gas emissions as carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e) (Ministry for the Environment, 2018a).

New Zealand largely relies on use of the “gross-net” approach to account for LULUCF emissions in its base and target years. However, it has also based its strategy on using Emissions Reduction Units (ERUs), as well as LULUCF credits, to meet a significant part of its first Kyoto commitment period (2008–2012) target, and then carrying over surplus Assigned Amount Units (AAUs) to achieve its 2020 target—raising questions about New Zealand’s commitment to satisfying its targets with environmental integrity.

In addition to the use of Kyoto rules for meeting its 2020 target, New Zealand is considering a completely new type of LULUCF accounting rules, which include the accounting of an “average carbon stock” for any new forests planted. These alternative accounting rules could be used to avoid large future carbon liability hits when plantation forests are harvested (Young & Simmons, 2016). The set of rules was described in further detail under the ETS consultation (Forestry New Zealand, 2018b). However, the lack of transparency around them means their effect on overall emissions is as yet unclear.

1 The Kyoto rules New Zealand seeks to apply, broadly relate to: (i) The carry over of surplus emission units and allowances from the first commitment period; (ii) The ability to generate LULUCF credits during the CP2 period; (iii) The ability to purchase and sell Kyoto emission units from other Kyoto Parties during CP2; and (iv) Provisions relating to the carryover of any surplus from earlier commitment periods to the post-2020 period.

Long-term goal

In 2011, the New Zealand Government announced its long-term target: a 50% reduction in GHG emissions from 1990 levels by 2050. Based on new LULUCF sector emissions projections for 2050, we estimate this translates to emissions levels of between 58–83 MtCO2eq in 2050. However, similar to the 2020 and 2030 targets, uncertainty is added by the indented accounting approaches suggested by New Zealand for the achievement of this target.

The Government has stated that “the 2050 target is based on New Zealand’s net GHG emissions and will take into account any removals or emissions arising from afforestation or deforestation since 1990 consistent with the Kyoto Protocol under the United Nations Convention Framework rules on climate change”(Government of New Zealand, 2011). The NDC text, as well as the latest National Communication and Biennial Report, reiterate New Zealand’s intent to meet this target making use of Kyoto accounting rules.

The Government is currently consulting on setting a more ambitious long-term target that would be set in legislation. In its consultation document on its proposed Zero Carbon Act, released in June 2018, the Government sought feedback on three target options for 2050:

- Option 1: achieving net zero CO2 emissions (so excluding CH4 and N2O emissions)

- Option 2: achieving net zero emissions for long-lived GHGs (i.e. CO2 and N2O) and stabilised emissions for short-lived GHGs (i.e. CH4)

- Option 3: achieving net zero emissions across all GHGs

An overwhelming majority of the 15,000 submissions received (91%) supported the third option (Ministry for the Environment, 2018d).

After the government completes negotiations with the opposition, it will begin drafting the Zero Carbon Bill, which is expected to be introduced into parliament in early 2019 (Office of the Minister for Climate Change, 2018). The bill is expected to establish the Climate Change Commission, which is likely to have an advisory role to the government (96% of submitters supported its establishment) (Ministry for the Environment, 2018c). The government has already created an interim Climate Change Committee to advise it until the Commission is set up (New Zealand Government, 2018). One of the first jobs of the Climate Commission will be to draw up five-yearly carbon budgets, after which the Government will then begin to create policies to achieve them.

The Productivity Commission has undertaken modelling to examine pathways from current levels to two alternative long-term targets: a 60% reduction from 1990 levels (around 26 MtCO2e including LULUCF in AR4 GWPs) and a more ambitious target of net-zero emissions by 2050. The main conclusion of the modelling exercise is that under all the scenarios modelled both targets are feasible, but immediate action is needed to increase their feasibility (Productivity Commission, 2018).

The findings of the Productivity Commission confirm previous results by other modelling groups that conclude that in order to be on a trajectory toward emission-neutrality around mid-century, substantial strengthened action in the agriculture and forestry sectors is needed in addition to efforts to decarbonise the energy system further (Vivid Economics, 2017).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter