Country summary

Assessment

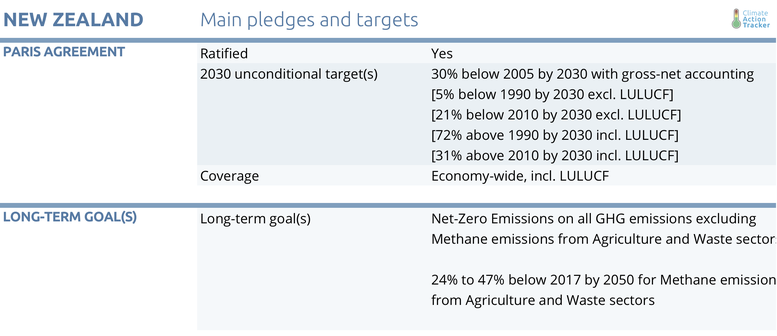

While New Zealand is showing leadership by having passed the world’s second-ever Zero Carbon Act in November 2019, under currently policy projections, it is set to miss its “insufficient” 2030 unconditional target by a wide margin, as it lacks the strong policies required to implement it. There is as yet no signal from the Government that it intends to submit an updated and more ambitious NDC by 2020.

Adopting the Zero Carbon Act is a step forward, but implementation is key. The Zero Carbon Act does not introduce any policies to actually cut emissions but rather sets a framework. Laws in place since 2004 for both land and the marine environment specifically prevent planning bodies from considering the impact on climate change of high-emitting projects when going through the consent process, allowing projects such as gas-fired power stations and coal-fired boilers at dairy plants to proceed. It is unclear whether these will be repealed, but they are a direct threat to the efficacy of the Zero Carbon Act.

At present the Government is relying on emissions removals such as through forestry and the purchase of international units, which will still allow emissions to be released into the atmosphere in 2050 to a level rated by the CAT from insufficient to the border of highly insufficient to hold warming to below 2°C, let alone limiting it to 1.5°C as required under the Paris Agreement.

Coal consumption in New Zealand is dominated by the industrial sector, including dairy and meat processing followed by non-metallic product manufacturing, only regulated by the country’s emissions trading scheme and already heavily subsidised.

The second largest fossil-fuel consuming sector, transport, has recently seen a backdown on its electric vehicle programme.

The Zero Carbon Act aims to achieve net zero emissions of all greenhouse gases, except for methane emissions from agriculture and waste, by 2050. Methane emissions from these two sectors, which represent about 40% of New Zealand’s current emissions, with the lion’s share from agriculture, are covered by a separate target of at least 24-47% below 2017 levels by 2050, with an interim target of 10% by 2030.

While the Zero-Carbon Act recently adopted strengthens its former New Zealand’s 2050 target (halving its greenhouse gas emissions by 2050), excluding such a substantial share of emissions from the net zero goal lowers its ambition.

To reach its 2050 emissions target, the government has recently proposed an Emissions Trading Reform Bill that continues to exempt the country’s largest greenhouse gas sector emitter – agriculture - from a price on its emissions until 2025, when it was originally proposed to cover all sectors’ emissions, and subsidising allocations up to 95%.

The Zero Carbon Act will establish an independent Climate Commission to oversee a five-year carbon budgeting process to drive the required emission reductions. The Commission will also advise on future revisions of the 2050 target, the use of international credits and the extent to which emissions may be banked or borrowed from one budget to the next. The comparable climate advisory body in the UK unequivocally advised its government in February not to bank emissions from that country’s second carbon budget. New Zealand’s Climate Change Minister has called the practice “dodgy accounting”.

The CAT rates New Zealand’s 2030 emissions reductions target as “Insufficient”, and its current policy projections do not put it on track to meet this target.

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern has vowed to make New Zealand a climate leader. According to our analysis, this would mean:

1) implementing strong policies to reduce emissions quickly,

2) updating the Paris Agreement 2030 emissions reductions targets, including abstaining from carry-overs and other creative accounting rules, and

3) strengthening the long-term target, through including biogenic methane emissions in the 2050 net-zero emissions target.

We would expect to see PM Ardern taking a leading role globally by updating the country’s 2030 NDC to a level of ambition in line with the 1.5° temperature limit.

New Zealand’s Paris Agreement-NDC target—of a 30% reduction from 2005 levels by 2030— is rated as “Insufficient,” meaning that it is not consistent with holding warming to below 2°C, let alone limiting it to 1.5°C as required under the Paris Agreement, and is instead consistent with warming between 2°C and 3°C.

If the CAT were to rate New Zealand’s projected emissions levels under current policies, we would rate them “Highly Insufficient,” indicating that New Zealand’s current policies are not consistent with holding warming to below 2°C, let alone limiting it to 1.5°C as required under the Paris Agreement, and are instead consistent with warming between 3°C and 4°C.

To reach its net zero target, New Zealand plans to add any emissions or removals from the land use, land use change, and forestry (LULUCF) sector and to use extensively carbon market mechanisms such as the purchase of emissions units. Historically, New Zealand’s LULUCF sector has represented a big carbon sink. The extent of the sink in 2050 is unclear therefore is as well the amount of remaining emissions by then. New Zealand’s “Kyoto forests”—largely exotic pine plantations planted in the early 1990s—are due to be harvested in the next few years. This will result in a massive reduction in the carbon sink of 20 MtCO2e/year between 2015 and 2030. This stands in strong contrast with recent scenarios modelled by the New Zealand Institute for Economic Research and analysed in the Regulatory Impact Statement from the Ministry of Environment , which would require the LULUCF sector to increase the sink by between -16 to -23 MtCO2e/year by 2050 (Ministry of the Environment, 2019; New Zealand Institute of Economic Research, 2018). The Government has a policy to plant one billion trees by 2030; however, it is unclear as to the planned mix between exotic trees and permanent indigenous forests, adding further uncertainty to projections.

Alongside the development of the Act, the government is also in the process of establishing the New Zealand Green Investment Finance Ltd. The 2018 budget earmarked NZ$100 million for the new institution. The purpose of the institution is to catalyse investment in low-emissions initiatives. It is supposed to begin developing its investment pipeline in June and make its first investments by the end of the year.

New Zealand’s main instrument to reduce greenhouse gas emissions is an Emissions Trading Scheme (NZ-ETS). The government has recently proposed a revised version of the policy for which, despite an election pledge and coalition agreements to bring agriculture into the NZ-ETS, it announced in October 2019 that emissions from agriculture sector will not be included until at least 2025, and will be able to claim up to 95% of free allocations. This is a major backdown when agricultural emissions represented in 2017 close to 48% of the country emissions excluding forestry.

It is also planning to remove the current $25 cap on the carbon price no later than 2022. Under the former scheme, the Emissions Intensive, Trade Exposed (EITE) industries – biggest industrial polluters which include companies such as the giant Rio Tinto – have been granted subsidies for up to 90% of their emissions. In the amended bill, the subsidy rate will gradually decrease to reach 80% by 2030, 60% by 2040, and 30% by 2050, which not only allows these companies to continue emitting, but at the expense of the state.

After agriculture, transport is the second largest source of emissions in New Zealand. It has one of the oldest passenger vehicle fleets in the developed world and no emissions standards. In August 2019, in response to the Productivity Commission report, the Government announced its Climate Action Plan which includes a backdown on its announced pledge to make the Government's own vehicle fleet fully electric by 2025. The Government aims now that all new vehicles entering the Government fleet are fully electric by mid-2025. The government is also in the process of developing a national rail plan to be released this year. The 2019 Budget included substantial increases in funding for rail and ferry services.

In November 2018, the Government banned new offshore oil and gas exploration. The Government has now turned its attention to how to support the hydrogen economy. Hydrogen can assist in decarbonisation a number of ways, particularly with respect to the industry sector. However, it is important to distinguish between 'green' hydrogen produced from renewable energy and ‘brown’ hydrogen produced from fossil fuels. ‘Brown’ hydrogen causes a substantial amount of emissions and is thus in compatible with a 1.5°C world. Advocacy groups have called on the New Zealand government to develop guidelines regarding the source of hydrogen production and to only support green hydrogen production.

New Zealand's planning laws still stand in the way of preventing high-emitting projects - such as the proposed gas-fired power stations in Taranaki - from gaining consent at local and regional level. A 2004 amendment to the Resource Management Act inserted clauses stating that a regional council "when making a rule to control the discharge into air of greenhouse gases...must not have regard to the effects of such a discharge on climate change." The same laws apply around the nation's exclusive economic zone legislation. The Government is conducting a review of the entire Act, but it is far from clear that it these clauses would be repealed: a direct threat to the Zero Carbon Act.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter