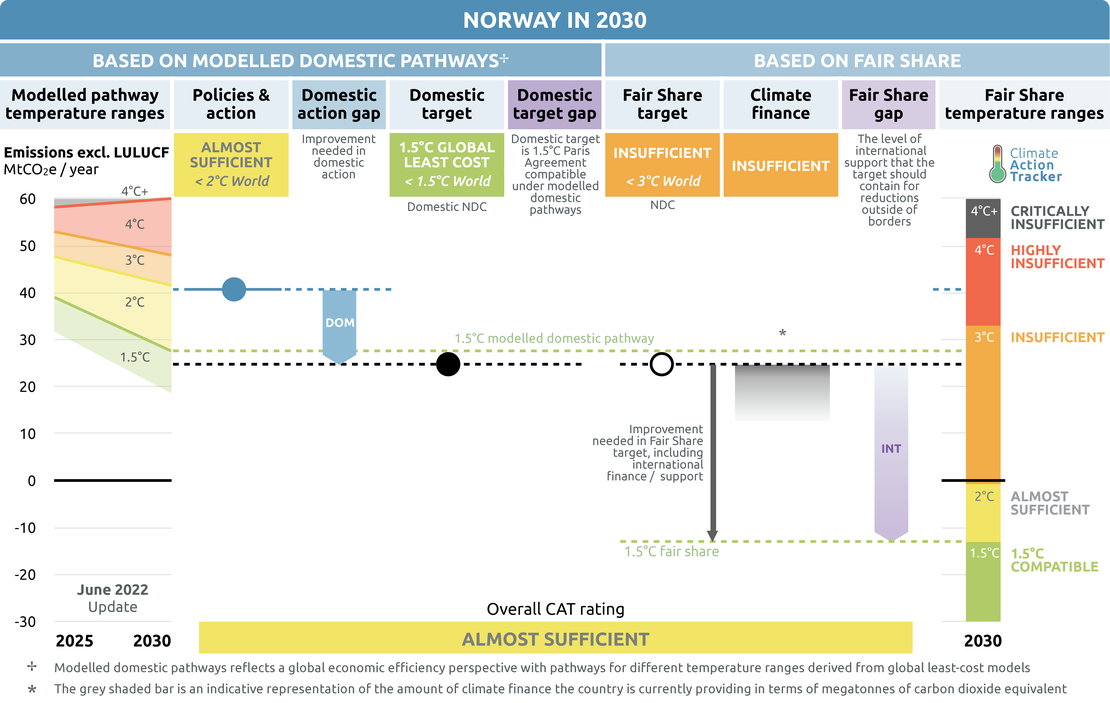

Policies & action

The CAT rates Norway’s policies and action as “Almost Sufficient”.

The “Almost sufficient” rating indicates that Norway’s climate policies and action in 2030 are not yet consistent with the 1.5°C temperature limit but could be, with moderate improvements. If all countries were to follow Norway’s approach, warming could be held at—but not well below—2°C.

Current policies are projected to lead to emission levels of 41MtCO2e by 2030 (excluding LULUCF), which is 21% below emissions in 1990. Norway will need to adopt further policies in order to meet its updated 2030 target.

Policy overview

Since 1990, GHG emissions in Norway have decreased only slightly reaching 49 MtCO2e in 2020 (excluding LULUCF). Under current policy projections, Norway will be far off its 2030 target, as GHG emissions are projected to reach 41 MtCO2e by 2030 or around 21% below 1990 levels. This illustrates the need for further policies and measures to reduce emissions.

A key plank of Norway’s recently updated Climate Action Plan is the gradual raising of its carbon tax to reach NOK 2,000, or USD 220 per tonne of CO2 by 2030 (Government of Norway, 2021c). However, it is not shown how the measures outlined in the plan will enable the achievement of Norway’s climate targets, as there is no quantification of the impact of such policies. Such a quantification will be included in Norway’s upcoming fifth biennial report to the UNFCCC and eighth national communication, both due by the end of 2022. There is no review mechanism outlined that would calculate the impact of the Norway’s carbon tax price or prospective increases, something that is critical to ensure the price is at the level necessary to achieve the stated emissions reduction targets.

A share of the country’s reduction requirements could rely on international climate action and purchase of emissions quotas under the European regulatory framework. Such investments and purchases abroad are grounded on the cost-efficiency argument, considering that reductions in other countries are, overall, cheaper than more aggressive national policies.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Norwegian government presented an economic recovery package of USD 2.8 billion (NOK 27 billion). Only a small share (NOK 3.6 billion), however, was reserved for green measures (Sfrintzeris et al., 2020). At the same time, the oil and gas industry and the aviation sector received substantial support. This included an amendment of the Petroleum Taxation Act to temporarily allow oil and gas companies to deduct investments from the tax base. Companies may also claim the tax value of losses incurred in 2020 and 2021 from the State (Lovvedtak 135 (2019–2020): Vedtak Ti l Lov Om Endring i Lov Om Skattlegging Av Undersjøiske Petroleumsforekomster Mv. (Petroleumsskatteloven), 2020). Economists advised against this measure, warning it would likely lead to prolonged oil extraction at a time when the country should move away from fossil fuels (Bjørnestad, 2020; Losnegård et al., 2020). The Norwegian government also supports the aviation industry including with state-guaranteed loans for Norwegian Air, SAS Wideroe (Dunn, 2020).

Norway’s oil and gas sector continues to be a large emissions source, making up over a quarter of total emissions in 2020 (Statistics Norway, 2022b). Given its large exports, it is also a large source of emissions in countries consuming its fossil fuel products (Scope 3 emissions). The newly elected government has refused to consider a phase-out of this sector, confirming its commitment to allowing an expansion of drilling and exploration in the Barents Sea, though this decision is currently being challenged in the European Court of Human Rights (Schwartzkopff, 2022).

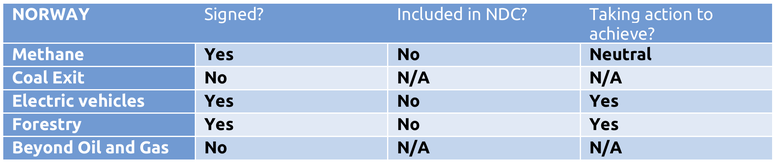

Sectoral pledges

In Glasgow, four sectoral initiatives were launched to accelerate climate action on methane, the coal exit, 100% EVs and forests. At most, these initiatives may close the 2030 emissions gap by around 9% - or 2.2 GtCO2e, though assessing what is new and what is already covered by existing NDC targets is challenging.

For methane, signatories agreed to cut emissions in all sectors by 30% globally over the next decade. The coal exit initiative seeks to transition away from unabated coal power by the 2030s or 2040s and to cease building new coal plants. Signatories of the 100% EVs declaration agreed that 100% of new car and van sales in 2040 should be electric vehicles, 2035 for leading markets, and on forests, leaders agreed “to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030”.

NDCs should be updated to include these sectoral initiatives, if they aren’t already covered by existing NDC targets. As with all targets, implementation of the necessary policies and measures is critical to ensuring that these sectoral objectives are actually achieved.

- Methane pledge: Norway signed the methane pledge at COP26, which is significant given its large oil and gas sector, and the considerable methane emissions it generates. A commitment to target a reduction in methane emissions has not, however, been included in Norway’s NDC, despite making up a tenth of Norway’s total GHG emissions in 2020 (Government of Norway, 2022).

A 30% reduction in methane emissions below 2020 levels would represent a decline of 1.5 MtCO2e. A regulation prohibiting the depositing of biological waste into landfills and a 2002 directive mandating the extraction of methane emissions from landfills with biodegradable waste have led to a 53% reduction in landfill methane emissions between 1990 and 2020 (Government of Norway, 2022; Norwegian Environmental Agency, 2020).There have been no recent policy developments to target further reductions in other sectors. - Coal exit: Norway has not adopted the coal exit agreement from COP26. Given Norway’s very high proportion of renewable power generation, there is negligible combustion in Norway, so the ramifications for not adopting the agreement are limited. Consequently, there is no mention of coal phase-out nor a targeting of coal-related emissions in Norway’s NDC.

- 100% EVs: Norway adopted the EV pledge at COP26. Norway leads the world on EV adoption, with its 2025 phase-out of fossil fuel vehicle sales far ahead of the COP26 pledge of 2035, and its very high proportion of EV sales, reaching 86% in February 2022. Its 2025 target is far ahead of the 20 Encouraging EV adoption is mentioned in Norway’s NDC, but its 2025 target is not. Norway is currently on track to achieve its 2025 target due to a slew of policies implemented over many years including several still currently in place (see Transport section below).

- Forestry: Norway signed the forestry pledge at COP26. Its most recent NDC includes a reference to legislation covering the period 2021-2030 that commits Norway to ensuring emissions do not exceed removals in the LULUCF sector. Specific measures are also outlined in Norway’s most recent Climate Action plan (see Forestry section below).

- Beyond Oil & Gas: Norway has not joined the ‘Beyond Oil & Gas’ initiative to end oil and gas exploration and production. On the contrary, it is currently planning to increase both oil and gas production.

Energy supply

Electricity generation in Norway is almost exclusively renewable. In 2020, 90% of electricity was generated by hydro power plants - Norway has over 1000 storage reservoirs that correspond to 70% of annual Norwegian electricity consumption (Norwegian Ministry of Petroleum and Energy, 2022). Depending on the weather in a given year, Norway can be either a net importer or exporter of power, and when exporting a considerable supply of power, this contributes to lower the overall carbon intensity of neighbouring countries’ electricity consumption. This zero-carbon power is also often used on an hourly or daily basis to help balance the grids of neighbouring countries.

A further 8.5% of electricity generation was from wind farms; the combined renewables share of over 98% can be seen in the figure below. Less than 2% of generation came from thermal power plants, mostly from industrial installations. As a result, the emissions intensity of Norwegian electricity is very low – around 19gCO2/kWh in 2019, in comparison to over 300gCO2/kWh for the EU (European Environment Agency, 2021).

Share of renewable electricity generation

Industry

Emissions from the industry sector play a much more important role in Norway than in many other countries as a result of Norway’s large oil and gas extraction sector. Norway is home to the biggest hydrocarbon reserves in Europe, making it the fifth largest exporter of crude oil in the world. In 2021, the oil and gas sector constituted around 60% of Norway’s exports (Statistics Norway, 2022c). Such a heavy reliance fossil fuel exports places Norway’s economy at risk given the 1.5°C temperature goal and is a strong impetus to diversify away from oil and gas production. In 2020, oil and gas extraction contributed 27% of the country’s emissions (Statistics Norway, 2022b). Norway now produces more oil and gas than the EU27 and the UK combined, as shown in the Figure below.

Oil and gas production

Historically, Norway’s most important instrument to tackle GHG emissions has been the carbon tax on petroleum activities levied on offshore drilling since 1991. In 1999, under the White Paper on energy policy, the government adopted additional energy and CO2 taxes. The taxation level is not the same for all sectors, with higher rates for oil extraction-related activities. Overall, around 80% of GHG emissions are taxed and/or regulated through the EU ETS, with most industries currently taxed at around NOK 590 or USD 59.6 (Buli & Adomaitis, 2021).

The emission intensity of Norwegian oil and gas extraction is, at 55 kgCO2 per tonne oil equivalent (toe), significantly lower than the world average of 130 kgCO2 (Gavenas et al., 2015). The Norwegian carbon tax, which was introduced in 1991, is one of the factors that explains its relatively low emissions intensity (Gavenas et al., 2015). This is due in part to the fact that it has helped to make carbon, capture and storage (CCS) viable on its oil and gas fields, with almost 1 MtCO2/yr being captured and stored since 1996 (Norwegian Petroleum, 2020). In 2015, Norway was ranked sixth out of 50 countries in terms of the lowest emissions intensity of crude oil extraction (Masnadi et al., 2018). Its performance in this regard compared to nearby Russia is shown in the Figure below. In April 2019, the leader of the opposition Labour Party called for setting a deadline for oil extraction to become fully emissions free (Holter, 2019).

Oil and Gas emissions intensity

In 2021, Norway’s state-owned coal company announced it will close its last mine in the Arctic area of Svalbard in 2023 (Reuters, 2021). The mine currently supplies a local coal power plant, one of very few remaining in Norway, that will be closed in 2023, with the main Svalbard settlement switching to diesel fuel temporarily before transitioning fully to renewable energy.

In a minor sign of progress, the Norwegian government agreed not to grant any oil and gas exploration licenses for virgin or little-explored areas in 2022 (The Local, 2021). This does not exclude new licenses to be granted for areas that have already been heavily exploited, with new licenses for such areas offered in March 2022 (Reuters, 2022).

This comes on the heels of a decision by the European Court of Human Rights to take up a case that is challenging Norway’s plans for new oil and gas drilling in the Barents Sea (Schwartzkopff, 2022). The case charges that approval of such permits would constitute a breach of fundamental human rights. In April 2022, the Norwegian government requested the case be found inadmissible, with that decision still pending as of June 2022 . The court noted that this case may potentially be designated an “impact” case, which could provide a new route for holding governments accountable for similar actions.

In the decade to 2022, the Norwegian government awarded more than 700 oil and gas exploration licenses, more than in the previous 47 years (Oil Change International, 2022). These licenses represent 2.8 billion barrels of new oil and gas resources, and if development of oilfields already licensed but not producing is permitted, this could lead to an additional 3 GtCO2 of emissions abroad if these fuels are sold and consumed.

The Norwegian Government supported investment in carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects by setting aside NOK 80 million (USD 9.6 million) in 2018 to fund Front End Engineering and Design (FEED) studies (Ministry of Petroleum and Energy., 2018). In January 2019, Norway’s Ministry of Oil granted a license to the country’s major, state-owned, energy company, Equinor (formerly Statoil) to develop carbon storage, aiming to receive around 1.5 MtCO2 annually from onshore installations (Reuters, 2019). In September 2019, Equinor signed preliminary agreements with potential customers, including cement and steel companies, to develop a subsea storage for up to 5 MtCO2 in the framework of the Northern Lights project (Adomaitis, 2019). Equinor is currently also investigating whether CO2 from a cement factory Brevik and/or a waste incineration plant in Oslo can be stored in a reservoir in the North Sea (Government of Norway, 2020b).

Norway’s government-owned climate investment body Enova announced an investment of EUR 100m in clean hydrogen production for three separate industrial projects, but just under three quarters of this funding will go towards producing ‘blue hydrogen’ from natural gas with carbon capture and storage (Bellona, 2021). The remaining EUR 27m will go towards producing renewable hydrogen. Funding blue hydrogen to such an extent is questionable given it still produces emissions and the vast renewable resources available to Norway for producing renewable hydrogen. In March 2022, Norway and Germany agreed to conduct a joint review to investigate the potential for large-scale transportation of hydrogen from Norway to Germany. A joint statement indicated that the intention is to utilise blue hydrogen for a transition period, with the German Economy Minister Robert Habeck indicating his preference for receiving ‘green’ hydrogen produced through electrolysis powered by renewable energy.

Transport

The decarbonisation of Norway’s transport system is one of the three main goals of its National Transport Plan (NTP) 2022–2033 (Government of Norway, 2021a). This plan includes a target to reduce transport emissions by 50% below 2005 levels by 2030 (36% below 1990 levels). Since the power sector is largely decarbonised, Norway has been focusing on reducing emissions in the transport sector to help achieve emission reduction rates similar to the EU (with whom they share the same reduction target).

Emissions from road transport decreased by almost a fifth between 2015 and 2020 (from 10.1 MtCO2 in 2015 to 8.2 MtCO2 in 2019) (Government of Norway, 2022). Indeed, the transport sector has shown the largest drop in emissions in recent years, an outlier relative to many other countries where transport emissions have either been stagnant or rising.

The Government allocated NOK 1,076 (USD 118) billion to realise initiatives in the NTP, including (Royal Ministry of Finance, 2019)expansion of the rail network and improving existing services, but almost half of this funding is allocated to roadworks, something that is primarily a byproduct of Norway’s low population density.

The rapid increase in sales of electric vehicles in Norway is unmatched anywhere in the world. In 2021, zero emission passenger vehicles reached a 65% market share, compared to 54% in 2020, and 42% in 2019 (Klesty, 2022). The market share of zero emission vehicles and plug-in hybrid vehicles combined reached 86% in February 2022, placing Norway on track to reach 100% as early as the end of the year (Holland, 2022). Of the total passenger car fleet in Norway, 16% were fully electric by the end of 2020, with a further 6% hybrid electric (Ferris, 2022).

Historical, current and expected future battery electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles market share in Norway, the EU and the US

The increasing share of electric vehicles has had an impact on the average CO2 emissions of new passenger cars, reaching just 60 gCO2/km in 2019, less than half the 2019 EU average of 122 gCO2/km (EEA, 2021; OFV, 2020). The electrification of transport has also had an impact on overall emissions from this sector: after a continuous increase between 1990 and 2014, emissions from passenger vehicles declined by roughly a quarter between 2015 and 2020 (Statistics Norway, 2021b). Primarily as a result of the increased market share of electric vehicles, total sales of diesel and petrol have fallen for three years in a row by 336 million litres in total over this time. This is a larger decrease than the overall decline from the 1974 oil crisis, after the 1987 stock market crash and after the 2008 financial crisis (Norsk elbilforening, 2020).

Norway has established a number of electric vehicle incentives, including an exemption from 25% VAT on purchases, access to bus lanes, and a maximum charge of 50% of the full price for parking and ferry fees, which have been extended to the end of 2022 (Norsk elbilforening, 2021). With its legislation, Norway has targeted all new passenger cars and light vans to be zero-emissions vehicles by 2025, and that new city buses will be zero-emissions or run on biogas by the same target year (Government of Norway, 2021a). At the end of 2021, there was just 251 electric buses in Norway compared to over 2,400 diesel and gas buses (Statistics Norway, 2022a).

Electrification is also planned for railways, substituting old diesel-fuelled lines to achieve emission reductions, but also higher train speeds and cost competitiveness against road transport, given the country’s low electricity costs. By 2030, all heavier vans, 75% of new long-distance buses, and 50% of all new lorries should be zero-emission vehicles.

Norway is also a pioneer in electric ferries. The Norwegian parliament has passed a resolution which calls on the government to transform its fjords into a zero-emissions control area by 2026 (Brown, 2018). The world’s largest electric ferry launched in March 2021 which will transport passengers between the two cities of Moss and Horten, Norway’s busiest ferry route (Daily Scandinavian, 2021). Norway’s first electric ferry was brought into service in 2015. Avinor, which operates most civil airports in Norway and is fully owned by the state, aims to electrify all domestic aviation by 2040 (Avinor, 2018).

Buildings

Norway has tightened building regulations over the last two decades, resulting in direct emissions from the buildings sector decreasing by 76% between 1990 and 2019. In November 2015, new Building Codes called TEK17 were adopted, introducing stricter limits for different categories of new and refurbished builds that became binding for all homeowners in 2017: 100 kWh/m2 for single houses, 95 kWh/m2 for apartments and 115 kWh/m2 for offices (Buildup, 2015; Direkoratet for Byggkvalitet, 2017; Faschevsky, 2016).

Under the EU’s Energy Performance of Buildings directive, all new buildings should be near-zero energy buildings (NZEBs) by the end of 2020. This target was agreed upon by the Norwegian parliament in 2012, however, since then, a national definition of NZEBs has not been finalised, meaning that the target cannot yet be fulfilled (Brekke et al., 2020). The above numbers are not, however, in line with this target.

Homeowners are also encouraged to increase the share of renewables produced domestically. Should an equivalent of more than 20 kWh/m2 be produced on the property, the respective limit on energy consumption can be exceeded by 10 kWh/m2 (Buildup, 2015). The production of renewable energy should not justify an increase in gross energy consumption, as this will still lead to increasing emissions if fossil heating is in use.

Norway has also introduced a ban on fossil fuel (oil and paraffin, given the unavailability of natural gas) heating systems. This ban has been phased in since 2016 and has been in full force from 2020 onwards. The ban applies to both new buildings and renovations and both private homes and public spaces of businesses and state-owned facilities (Reuters, 2017). According to Norway’s Seventh National Communication this ban will reduce emissions in the country by 400 ktCO2 in comparison to business-as-usual (Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment, 2018a).

Norway has a substantial carbon sink in its forests which equals approximately half of Norway’s annual emissions. Since 2005 the forest area in this country has been increasing and in 2020 reached 33.4% of the land surface – around 0.2% more than a decade earlier (World Bank, 2021). The volume of growing wood stock increased between 2011-2020 by 12.5% (SSB, 2021).

According to its national forestry accounting plan, between 2021-2025 Norway’s average removals from this sector will amount to slightly over 24 MtCO2e (Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment., 2019). As part of its recently updated Climate Action Plan, Norway has committed to introduce a minimum logging age in its Forestry Act in line with the PEFC Forest Standard, and to facilitate afforestation of new land, though no quantitative targets were set (Government of Norway, 2021c). In November 2021, Norway signed the forestry pledge at COP26 that committed to halting and reversing forest loss and degradation by 2030 (UK Government/UNFCCC, 2021). Given Norway’s forestry sector is already an increasingly large emissions sink, this is not particularly ambitious.

In addition, Norway has pledged up to NOK 3 billion (USD 343 million) a year in the framework of the Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative (NICFI) to reduce deforestation in other countries (Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment, 2018b).

Finance

In March 2019, Norway’s government decided to follow on the advice of Norwegian Central Bank and phase-out investment of its Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG), worth around USD 1.35tn, in companies dealing with oil and gas exploration and production (Royal Ministry of Finance, 2018). This will result in gradually selling shares of 134 companies worth USD 8bn, increasing supply and consequently reducing share prices (New Scientist, 2019). Divestment announcements can also affect investor sentiment, potentially also negatively impacting prices and reducing firm profitability. While a belated step in the right direction, this decision will still allow the GPFG to invest in companies providing oil and gas services, such as BP or Shell, which currently constitute a significant share of the Fund’s investment amounting to USD 2.9bn and USD 5.9bn respectively (Norges Bank, 2019a). These efforts are part of a broader divestment campaign that has led to over USD 40tn in pledged divestment from fossil fuel companies (Global Fossil Fuel Divestment Commitments Database, 2022).

Following a proposal by a government-appointed commission in mid-2021 that the GPFG should push firms that it invests in to cut their GHG emissions to zero by 2050, the fund outlined its intention to be an “active shareholder” and push firms to make the transition to net zero emissions (Norges Bank, 2021). The GPFG specified that it would not divest from such companies that are major emitters of GHG emissions.

In June 2019, Norway’s Parliament voted to divest from eight coal companies and around 150 oil producers (Ambrose, 2019). As a result, stocks worth more than USD 10 billion will be divested. The Fund is no longer able to invest in any company generating more than 10 GW of electricity from coal or mining more than 20 million tonnes of coal annually (Nikel, 2019). This should be reduced to zero to send a stronger signal to companies that they must phase out coal as soon as possible.

In May 2020, Norges Bank – the Norwegian Central Bank – which manages the state-owned oil fund divested from five companies for their coal activities (Norges Bank, 2020). The fund was a major shareholder in all companies and its decision to divest sends a strong signal and may be followed by others (Milne, 2020).

Since 2019, the Oil Fund can invest in renewable energy projects that are not listed at the stock exchange (Ministry of Finance., 2019) and which represent 71% of the investable market. (McKinsey&Company, 2018). Since these projects come at a higher risks, the Government has introduced a cap on investments in unlisted renewable energy projects at 2% of the Fund, amounting to around USD 20 billion (Ministry of Finance., 2019). The 2020-2022 strategy document provides that renewable energy investment should make up 1% of the Fund towards the end of 2022 (Norges Bank, 2019b).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter