Pledges And Targets

Summary table

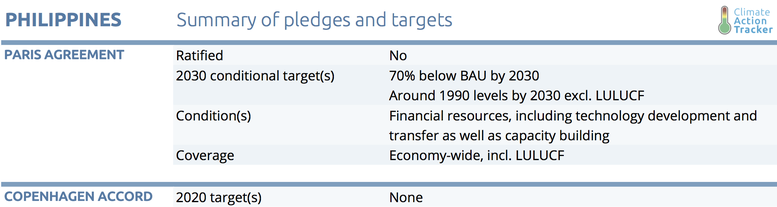

Paris Agreement

On 1 October, the Philippines submitted its Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), including a conditional target of a 70% reduction in GHG emissions below BAU projections by 2030. This emissions reduction target is conditional on financial resources, including technology development and transfer as well as capacity building. Even though the Philippines Senate cast an unanimous vote to ratify the Paris Agreement in March 2017 (ClimateAction, 2017), the Philippines has not yet submitted its NDC as of November 2017.

Uncertainty remains over whether President Duterte and his government will weaken the NDC’s ambition and revise its emission reduction target downward. In March 2017, Climate Change Commission Vice Chairperson Secretary Vernice Victorio indicated that the possibility to revise the Philippines’ NDC downward at a later point in time convinced President Duterte to ratify the Paris Agreement after the vote of the Philippine Senate (Ranada, 2017). In addition, the decision on the process and timeline to submit the NDC by 2020 remains unclear and is still pending (Fontanilla, 2017). For this assessment, the Climate Action Tracker assumes that the Philippines’ INDC became its NDC with the Paris Agreement ratification (UNFCCC, 2015). For this reason, we only refer to the NDC throughout this assessment.

Because the current NDC target does not distinguish LULUCF emissions reductions from reductions in energy, industry and agriculture emissions, and lacks a quantification of the BAU, the emissions reductions are difficult to estimate. Assuming the current policy projection (see the next section) is in line with BAU projections and the 70% emissions reductions are applied to non-LULUCF emissions, the NDC could result in emissions decreasing back to 1990 levels (excl. LULUCF).

In 2015, the Department of Energy (DoE) announced that more than 10 GW of coal-fired power plant capacity would be constructed in the Philippines by 2025 and released a Coal Roadmap 2017–2040 (Department of Energy, 2017b). If all these power plants were built, it would be difficult for the government to achieve its NDC target (excluding LULUCF), especially because the recent upswing of development in the coal industry has encouraged increased interest in coal exploration (Department of Energy, 2016a).

The current NDC covers all sectors including LULUCF, however, the NDC does not specify to which extent emission reductions ought to be achieved in each respective sector. There is high uncertainty particularly about reported emissions data in the LULUCF sector and their future projections. If the government expects larger carbon sinks from LULUCF than in our analysis, other sectors would have to decarbonise less to achieve the emissions reduction target.1 Although a net negative effect of the LULUCF sector contributes to global GHG emissions reductions, the decarbonisation of energy consumption and industry is pivotal to achieving long-term climate mitigation targets. A less ambitious emissions reductions target was hinted at in the Philippines’ draft NDC (Government of The Philippines, 2015b), with only a 10–20% reduction in GHG emissions from BAU in the energy sector.

The need for a transformation in all sectors is also recognised in the NDC as it states that the Philippines “views the need to peak its emissions as an opportunity to transition as early as it can to an efficient, resilient, adaptive, sustainable clean energy-driven economy, and it is determined to do so with partners from the global community.” A disentanglement in the commitment of LULUCF emissions from other emissions (from energy, industry and agriculture) would be in line with the mentioned transformation and peaking.

1 | This assumes that LULUCF emissions in the BAU scenario in 2030 are near zero, in line with the most recent estimate of actual LULUCF emissions in the Philippines from FAO (FAOSTAT, 2016) for 2012. Since the BAU is not provided in the NDC there is large uncertainty around the projected 2030 emissions assumed in the NDC.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter