Country summary

Assessment

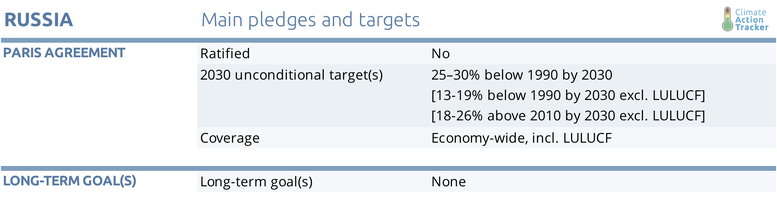

While it is more than likely that Russia will achieve its INDC target, the target is so weak that it would not require a decrease in GHG emissions from current levels—nor would it require the Government to adopt a low-carbon economic development strategy. As a result, we have given Russia our lowest rating: “Critically Insufficient.”

Despite its high vulnerability to the impacts of climate change (confirmed by a 2017 report from the Environment Ministry), Russia has made little progress in climate action implementation—indeed, the government is delaying the adoption of ambitious climate targets and policies, which has led to the Russian Federation being the only big emitter that has not yet ratified the Paris Agreement. Their national strategy may delay ratification.

Following his re-election for a fourth term, in May 2018 President Putin pushed for the country achieving a technological, environmental and economic breakthrough. The Environment Ministry then drafted the “Ecology” (Экология) programme focusing on air pollution reduction, reforestation, and improving waste management. None of the ten directions in the Ecology programme relate directly to GHG emissions reductions, although the “clean air”, “waste management” and “preservation of forest” could have important synergies with climate change mitigation. The budget that had been initially planned for the Plan was also cut by 17%.

In December 2018, the government introduced new draft legislation that would establish a cap-and-trade system for major carbon emitters by 2025 and require companies to report their emissions. The bill may be passed by parliament as early as June 2019.

Russia is likely to meet its INDC, because it is so weak.

According to our latest estimates, Russia’s currently implemented policies will lead to emissions of between 2.6 and 2.7 GtCO2e in 2020 and between 2.8 and 3 GtCO2e in 2030 (both excluding LULUCF), which is 0-4% and 6-14% above 2016 emission levels, respectively. This represents a decrease in emissions from 1990 levels of 27-29% in 2020 and 20-25% in 2030, all below the INDC targets, which allow emissions to grow 6–24% above 2016 levels by 2020 and 15–22% by 2030.

With this approach, the Russian economy is at risk of losing global competitiveness in the medium to long term in a market that is moving fast towards the development of low-carbon technologies.

A first step towards contributing to the Paris Agreement’s goalswould be for Russia to speed up the national process for ratification of the Agreement and present a 2030 target setting out actual emissions reductions beyond the current policy scenario. This would not only be more credible from an international perspective, but would also help to align national policy developments with the long-term emissions reductions needed to avoid dangerous levels of climate change, which represent high risks to the national economy.

The proposed new legislation would establish a cap-and-trade system for major carbon emitters by 2025 and require companies to report their emissions. It would allow the government to introduce targets for GHG emissions and charge companies for excess emissions, which would feed into the Emissions Reduction Support Fund. Despite objections by the Russian Union of Industrialists, Parliament may pass the law as soon as June 2019.

Since 2017, President Vladimir Putin seemed to have taken a U-turn in his public position regarding climate change and the Paris Agreement, returning to a sceptical attitude. Russia’s leadership has stated that it expects long-term risks for the national economy from climate change as well as from the global economic trends resulting from the implementation of the Paris Agreement. This neglects the significant short and medium-term risks that a low-carbon global pathway entails for an economy largely based on the export of fossil fuels and mineral resources.

These statements have been challenged by the findings of a 900-page report “On the status and protection Environment Russian Federation” of the Ministry of Natural Resources and Ecology, which breaks down the past and future consequences of climate change for the country. It concludes that Russia is already being hit by the natural disasters and other impacts of climate change, and projects this trend to increase in the future (e.g. heatwaves, widespread forest fires, epidemics, drought, mass flooding and food shortages).

In 2016 (the last year for which data is available) Russia’s energy sector accounted for 87.3% of all emissions without LULUCF. An increase in renewable energy investments in Russia has been observed recently, which will slow emissions growth. Between 2016 and 2017, Russia adopted three decrees and orders in the field of energy efficiency and promotion of renewable energy, including a plan of measures to further stimulate the development of generation facilities based on renewable energy sources with installed capacity up to 15 kW.

Installed renewable power generation capacity increased to approximately 54 GW by the end of 2017, equivalent to 21% of the country’s total power generation capacity, with hydropower representing the majority of the installed capacity (52 GW).

Under current policy projections, the upward trend in the share of renewable sources in primary energy demand will continue, from around 3.4% in 2016 to 4.3% by 2030. Russia has a 2.5% Renewable Energy Target for 2020 (excluding large hydro), which we estimate would increase the share of RE sources slightly to 4.4% of primary energy demand by 2030.

This upward trend and the increasing number of regulations promoting renewable energy deployment has been attributed to the benefits of renewable energy sources in Russia which include contributing to economic growth, diversifying the energy mix, and reducing energy supply costs in remote areas of the country.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter