Policies & action

We rate Saudi Arabia’s policies and actions against modelled domestic pathways as “Critically Insufficient”. This rating indicates that Saudi Arabia’s policies and action in 2030 reflect minimal to no action and are not at all consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C. If all countries were to follow Saudi Arabia’s approach, warming would exceed 4°C.

Further information on how the CAT rates countries (against modelled domestic pathways and fair share) can be found here.

Policy overview

Saudi Arabia has done little to decarbonise its economy. We expect its emissions to rise to 800–830 MtCO2e in 2030, a 15–19% increase from 2021 levels. It remains difficult to assess whether Saudi Arabia’s current policies reach its NDC target, given the significant uncertainties around its target (see details in the Assumptions section).

Saudi Arabia’s energy sector remains dominated by fossil fuels, which represented almost 100% of the total energy supply in 2022 (IEA, 2023b). The Saudi government expects the overall demand for energy, including for oil and fossil gas, to continue increasing until 2030 and beyond (KAPSARC, 2021).

Saudi Arabia’s “Vision 2030” aims to diversify its economy beyond oil, which accounted for around two thirds of total budget revenues in 2022. However, the government clearly has no intention to phase out fossil fuels. Saudi Arabia is betting on carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies as a smokescreen to continue expanding oil and gas production.

While Aramco abandoned its plan to increase oil production capacity to 13 million barrels per day (mb/d) by 2027, this decision appears largely driven by strategic considerations rather than a commitment to phase out fossil fuels. This reversal reflects changes in the global oil market, including slowing demand growth and increased production from non-OPEC countries, particularly the U.S.

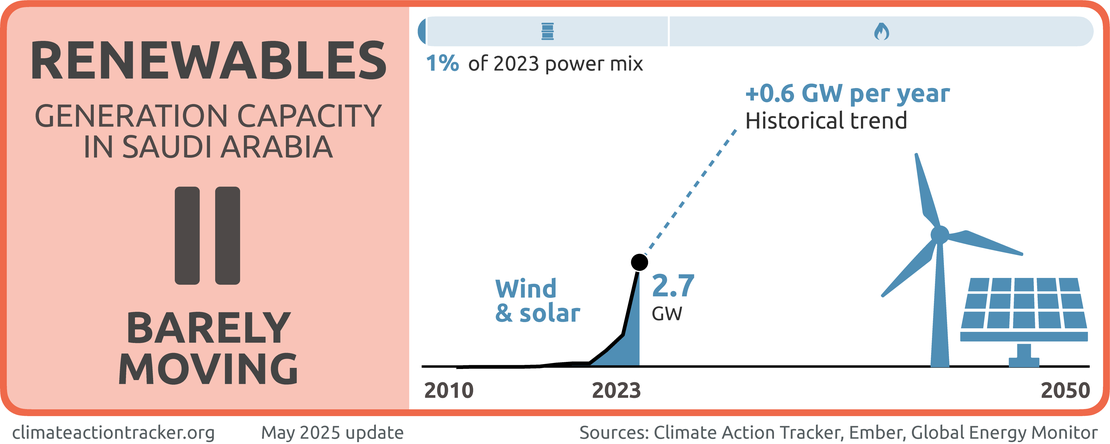

Even if Saudi Arabia were to reach its 50% target for renewable energy in the electricity mix, we project that emissions would still rise to 730–770 MtCO2e by 2030. Despite its vast solar energy potential, Saudi Arabia has only installed about 2.7 GW of renewable energy capacity as of 2023, generating around 1% of total electricity (IRENA, 2024b).

Carbon crediting schemes

In 2022, Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund, the Public Investment Fund (PIF), and the Saudi Stock Exchange Tadawul set up a voluntary carbon market in the Middle East and North Africa. The first auction in November 2022 offered one million tonnes of carbon credits (Bloomberg, 2022).

Saudi Arabia has also announced the launch of a domestic carbon crediting scheme in early 2024, which will purportedly enable companies to offset their emissions by buying credits compliant with Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. The scheme appears to be voluntary, project-based and covers all sectors (Carbon-Pulse, 2023; Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2024).

Despite the apparent focus on companies procuring credits, Saudi Arabia also appears to plan on using the credits to meet parts of its national climate pledge, including its 2060 net zero target. Based on the information published as of November 2024, it is unclear how this could work in practice in a manner that avoids both a company and the government from claiming rights to the same emission reductions ("double counting") – an outcome that would undermine the integrity of the credits, and potentially lead to an overall rise in emissions.

The establishment of a voluntary carbon market in Saudi Arabia should complement and not serve to distract from - or displace - critically-needed domestic mitigation efforts. Information on how the Kingdom intends to use its carbon crediting scheme remains unclear or lacks details, and presents major risks that it will seek to use carbon credits with questionable integrity as a smokescreen to justify continuing its trajectory of maintaining high levels of domestic emissions. For more information on the role of voluntary carbon markets under the Paris Agreement and their associated risks, see Fearnehough et al. 2020.

Power sector

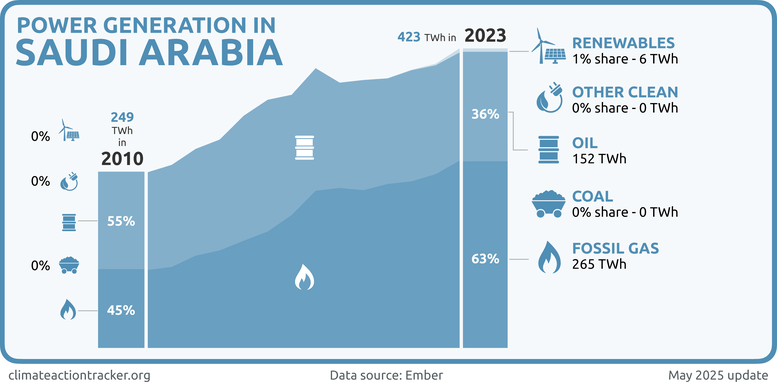

The power sector is the largest source of GHG emissions in Saudi Arabia. In 2023, Saudi Arabia still produced nearly 100% of its electricity with fossil fuels—around 63% with fossil gas and 36% with oil (Ember, 2025).

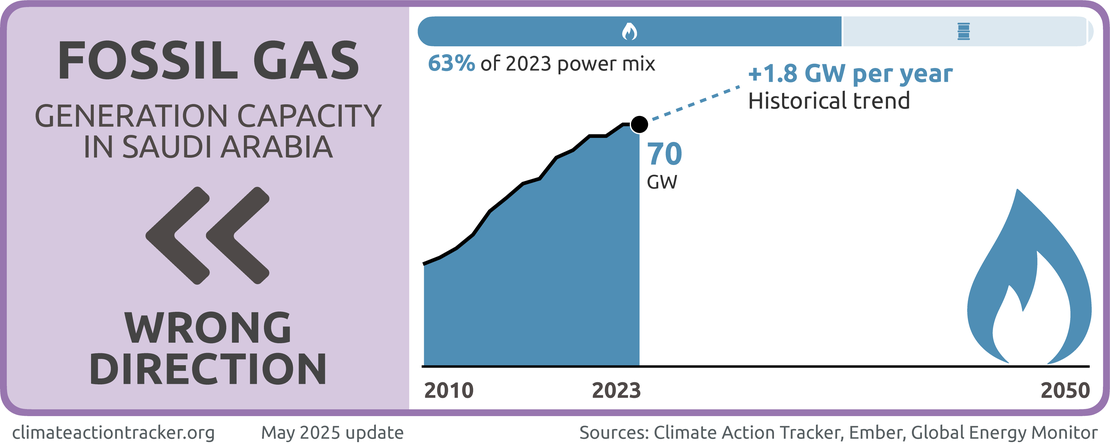

Fossil gas

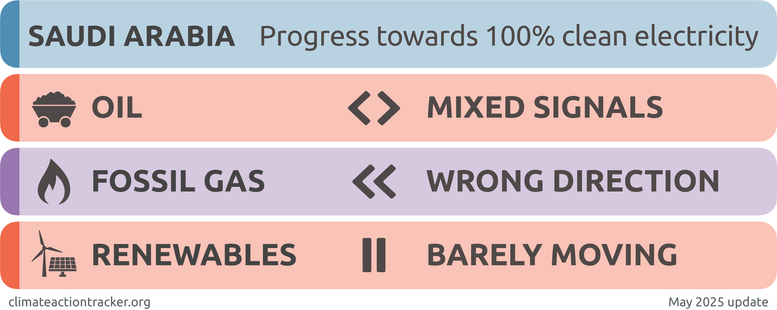

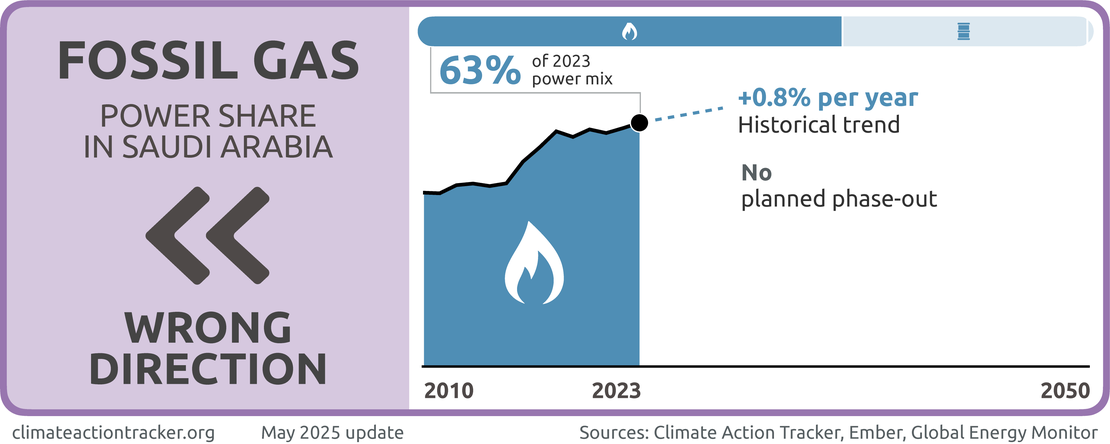

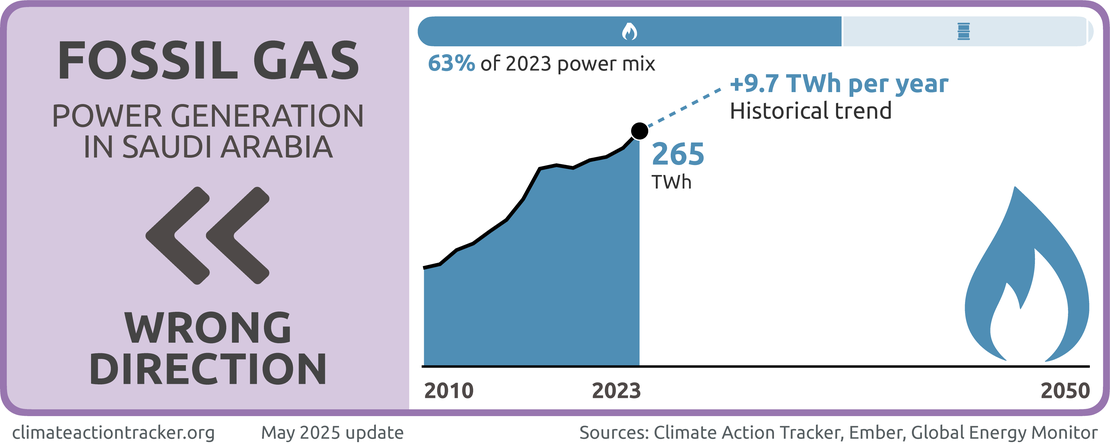

Saudi Arabia policy is headed in the “Wrong Direction” on fossil gas. The share of gas in the power mix has remained relatively stagnant in the last five years, but generation in absolute terms has increased from 224 TWh in 2019 to 265 TWh in 2025 (Ember, 2025). Saudi Arabia has no intention of phasing out fossil gas from its power sector. It currently aims for 50% of total electricity to be generated with fossil gas by 2030.

Saudi Arabia is planning to further expand its fossil gas power capacity, with a substantial number of projects currently under development. In December 2023, four gas-fired power plants with a total capacity of 5.6 GW started operation, and additional plants with a total capacity of 8.4 GW are currently under development (Saudi & Middle East Green Initiatives, 2023).

Fossil gas is a fossil fuel and needs to be phased out as part of the global decarbonisation needed to reach the 1.5˚C temperature warming limit—by 2035 in developed countries and 2040 in developing countries (Climate Action Tracker, 2023).

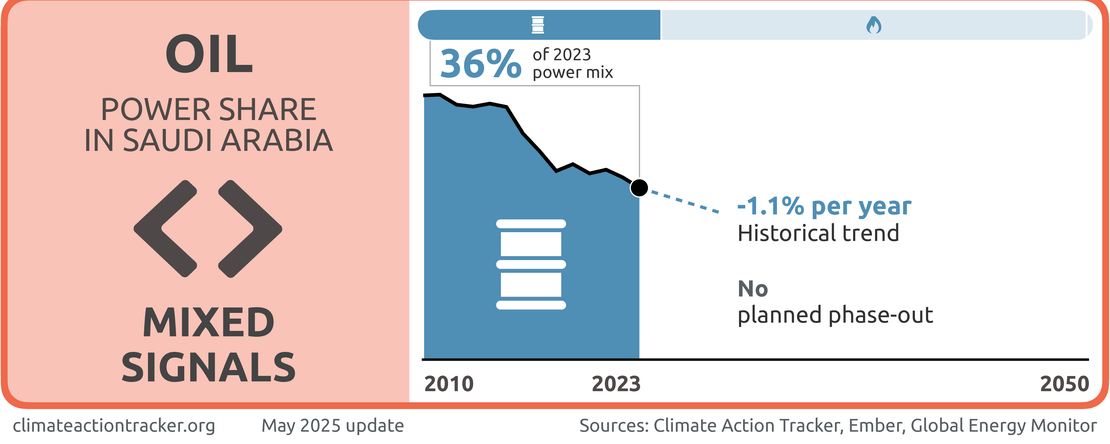

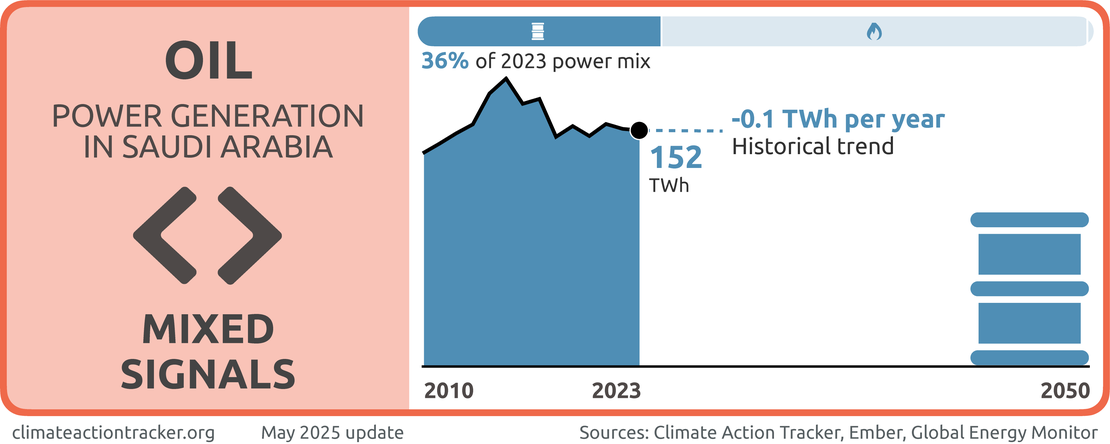

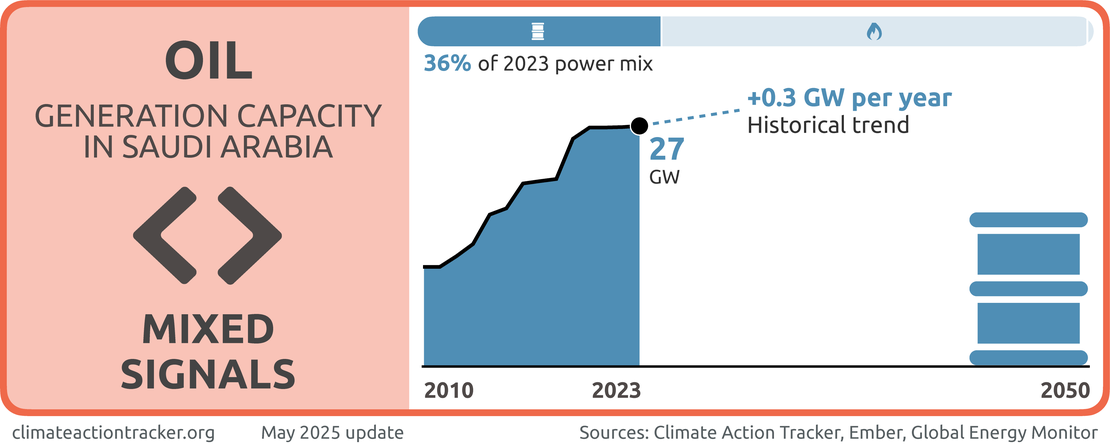

Oil

Saudi Arabia is sending “Mixed signals” on oil. While the Kingdom aims to fully phase out oil from its power sector by 2030, it remains off track. Although the share of oil in the power mix has decreased over the last five years, falling to 36% in 2023, absolute amount of oil generation has remained largely stagnant (Ember, 2025).

Fossil fuel subsidies

In 2022, Saudi Arabia had the G20's highest share of fossil fuel subsidies per capita (IMF, 2023). Fossil fuel subsidies, both direct and indirect, continue to distort energy prices by keeping oil and fossil gas prices artificially low, discouraging investment in cleaner alternatives.

Saudi Arabia, acknowledging the need for reform in its “Vision 2030” strategy, took initial steps to address this issue (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2021c). The government introduced a 5% VAT on fuel and increased VAT rate for goods and services from 5% to 15%, including those in the hydrocarbons sector (SPA, 2020).

However, fossil fuel subsidies (explicit and implicit) provided by the government jumped from USD 141bn in 2019 to USD 253bn in 2022, accounting for 16% of Saudi Arabia’s GDP in 2019, to 27% in 2022 (IMF, 2023). Driven by soaring energy prices and the demand rebound following the pandemic, these subsidies have primarily benefited the domestic oil sector.

Research shows that adequate pricing of fossil fuels could help cut 36% of global CO2 emissions (Parry et al., 2021). Setting prices that reflect the true costs of fossil fuels would also further increase the cost-competitiveness of mitigation technologies, such as renewable energy.

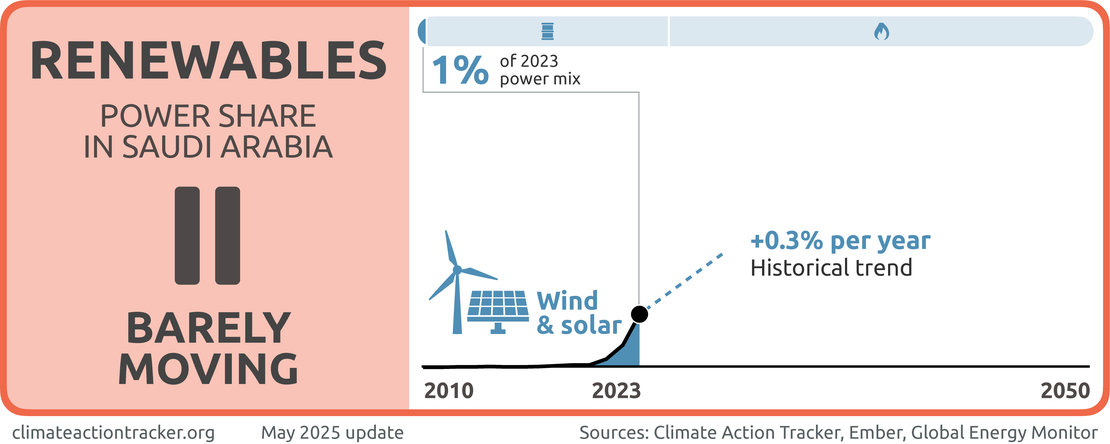

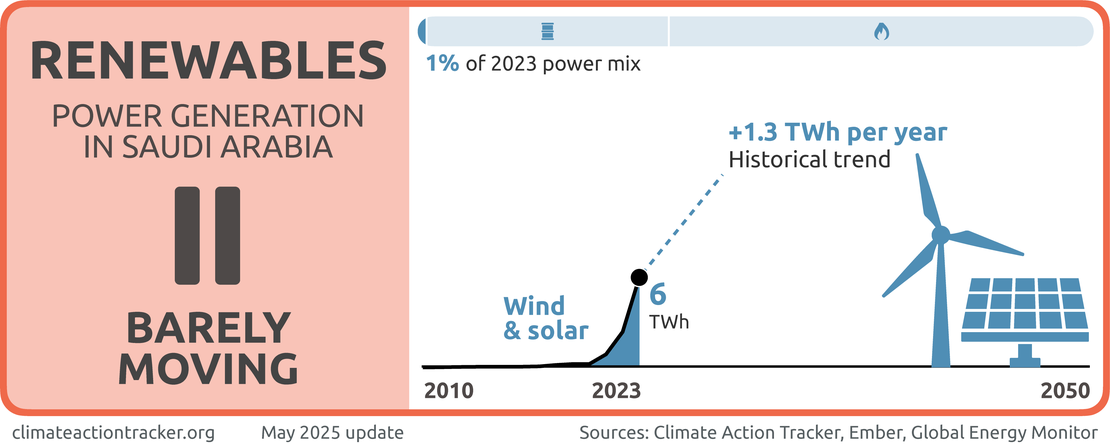

Renewables

The renewable energy sector remains in its fancy in Saudi Arabia. In 2023, installed renewable energy capacity stood at 2.7 GW, generating around 1% of electricity, with around 1.9 GW (mostly solar) additional capacity installed between 2022 and 2023 (Ember, 2025)

Despite its vast potential, Saudi Arabia’s renewable energy sector has been mired in uncertainty, with ambitious announced plans and projects having yet to materialise. In the first iteration of “Vision 2030” released in 2016, the government revised its renewable energy target downward to an ‘initial’ 9.5 GW installed capacity by 2023 (Borgmann, 2016; Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2016). In 2019, the Ministry of Energy released an updated version of the strategy, which aimed to install 27.3 GW of renewable energy capacity by 2023 and 57.8 GW by 2030. The latest target aims for 50% of electricity to be generated with renewable energy and 50% with fossil gas in 2030 (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2021c; Saudi Arabia, 2024).

Despite some limited progress in the last two years, the pace of renewables deployment in Saudi Arabia remains far too slow to meet the Kingdom’s latest 2030 target. We evaluate progress in this sector as “Barely Moving”.

Hydrogen

Saudi Arabia hopes to position itself as a leader in the global hydrogen market. The government announced plans to build a large green hydrogen production facility in its smart city NEOM (Al Arabiya News, 2023b; Saudi & Middle East Green Initiatives, 2023). The plant is expected to be operational in 2026 and produce 600 tonnes per day of green hydrogen using renewable electricity.

The government is pursuing “clean hydrogen” development with a view to diversifying its revenues and becoming less reliant on hydrocarbon exports (Saudi Arabia, 2024). Considering its strategic location near global shipping lanes and its vast renewable energy potential, Saudi Arabia is also well-positioned to lead the decarbonisation of the maritime sector. It has the potential to lead the way by producing green hydrogen at scale as an alternative fuel source (KAPSARC, 2023b). It should, however, first prioritise rapid scaling-up of renewable capacity to decarbonise the domestic economy.

Building the pipeline of renewable capacity to first meet domestic energy demand and then potentially exploiting the global market for “green” hydrogen will take time, given the low base of renewables in Saudi Arabia. A substantial policy commitment and investment in renewable electricity today is a critical enabler for Saudi Arabia to position itself as a future leader in “green” hydrogen. Without this shift in the status quo, it will only be able to rely on fossil gas and unproven CCS technologies to produce “blue” or “grey” hydrogen, neither of which are "renewable".

While hydrogen production from fossil gas has been the cheapest option to date, it remains expensive, as lot of energy is lost in the conversion process and is highly susceptible to market price volatility. Gas price fluctuations caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine tripled the cost of grey hydrogen in 2022. Emission penalties under carbon pricing are expected to further increase the cost of fossil fuel-derived hydrogen. On the contrary, with falling renewable energy costs and technology improvements, green hydrogen – particularly produced with solar PV and wind – could become cost-competitive with fossil fuel-derived hydrogen as early as 2030 (NewClimate, 2023).

Nuclear energy

Saudi Arabia has recently reiterated its intention to build a nuclear power plant, although no concrete plan had been announced as of November 2024 (World Nuclear News, 2023). While nuclear electricity generation does not emit CO2, the CAT doesn’t see nuclear as the solution to the climate crisis due to its risks such as nuclear accidents and proliferation, high and increasing costs compared to alternatives such as renewables, long construction times, incompatibility with flexible supply of electricity from wind and solar and its vulnerability to heat waves.

Grid infrastructure

In 2019, Saudi Arabia’s Renewable Energy Project Development Office (REPDO) completed a study claiming that 13.5 GW of renewable energy could be integrated without major grid upgrades (National Renewable Energy Program, 2018). Beyond this, and in order to meet its 2030 renewable energy target, the government will need to significantly invest in grid infrastructure.

Saudi Arabia is moving ahead with grid interconnection plans with neighbouring countries, focusing on smart grid technologies, which could facilitate a future uptake and integration of renewables (Al-Gahtani, 2024). Saudi Arabia is currently working on grid interconnection project with Iraq, India, Jordan and Egypt (RE Global, 2023).

Industry

Oil production

Oil extraction has been the backbone of the Saudi economy for decades. Saudi Arabia is the world’s second largest oil producer after the United States and is OPEC’s leading oil producer (BP, 2023). It produced approximately 12% of the world’s oil in 2022 and held 17% of proven oil reserves.

While the government has taken small steps to diversify the economy, Saudi Arabia remains highly dependent on hydrocarbon revenue. In 2022, Saudi Arabia reported USD 362bn in total crude oil export revenues and an additional USD 45bn in refined petroleum export revenues: several orders of magnitude higher than the oil export revenues from any other country (OEC, 2024). Oil is Saudi’s most exported commodity, accounting for 75% of the total value of exports in 2021 (OPEC, 2023).

Over the past two decades oil rents, which are the difference between crude oil market prices and production costs, have consistently contributed at least 20% of Saudi’s annual GDP (World Bank, 2021). This close dependency between Saudi’s GDP growth and the oil market puts the sustainable growth of Saudi’s economy at risk. Recent geopolitical conflicts have once more shown the vulnerability of the global oil market to exogenous shocks.

Saudi Arabia does not plan to end investment in new oil production, which is required to hold global warming to 1.5°C (IEA, 2023a). While Aramco recently abandoned its plan to increase oil production capacity to 13 million barrels per day (mb/d) by 2027, this decision appears largely driven by strategic considerations rather than a commitment to phase out fossil fuels. This reversal reflects changes in the global oil market, including slowing demand growth and increased production from non-OPEC countries, particularly the U.S (FT, 2024).

The government’s current diversification plans include no scenario with a decline in global oil consumption in the coming decades, which is required to meet the objectives of the Paris Agreement and reach net zero CO2 emissions by mid-century (IEA, 2023a; IPCC, 2018). Both the “business-as-usual” and the “2030 renewable energy target” scenarios outlined in KAPSARC’s Energy Policy Solutions project hydrocarbon exports to significantly increase until 2050 (KAPSARC, 2021).

At COP28, Saudi Aramco signed the Oil and Gas Decarbonisation Charter (OGDC), a new initiative which aims to “accelerate climate action” in the fossil fuel sector. However, the OGDC only addresses a fraction of relevant emissions from oil and gas production. Although most emissions come from fuel combustion, the initiative solely focuses on reducing emissions within the operations of oil and gas companies, such as in drilling and refining processes. Without a commitment to reducing the extraction and burning of fossil fuels, the charter fails to tackle the main driver of climate change. So far, none of the signatories have agreed to cut fossil fuel production.

Carbon capture and storage

Saudi Arabia is betting on carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies to reach its climate goals while sustaining its fossil fuel production and exports. As of 2024, it only had one operational CCS plant—which is used for enhanced oil recovery (EOR), rather than reducing emissions from fossil fuels (Global CCS Institute, 2023).

The government has a target to capture and store 44 million tonnes of CO2 annually by 2035. To this end, Saudi Arabia is in the process of building a CCS hub at the industrial complex of Jubail, which it plans to capture CO2 from fossil gas plants. The hub is expected to be operational from 2027 and the plans are to capture up to nine million tonnes of CO2 per year from three Aramco fossil gas plants (The CCUS hub, 2023). But given the track record of CCS technology so far, these planned capture rates are questionable.

CCS technologies are not commercially viable, nor are they proven at scale, despite large public subsidies for research and development globally. Relying on CCS to the extent Saudi Arabia is planning diverts attention and resources away from cost-effective mitigation options. The use of CCS should be limited to industrial applications where there are fewer options to reduce process emissions—not to reduce emissions from the electricity sector where there are cost-effective mitigation alternatives, not least because CCS does not remove 100% of emissions from power plants.

Saudi Arabia is promoting the concept of a Circular Carbon Economy (CCE) to reduce emissions from oil and gas production (Luomi et al., 2021). This, however, only addresses a fraction of relevant emissions as most emissions come from fuel combustion rather than oil and gas extraction and processing. Saudi Arabia’s CCE plans largely rely on the development and deployment of CSS technologies (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2022).

Transport

The transport sector accounted for 29% of total final energy consumption in 2022 (IEA, 2024).

The sector is primarily individual, road-based transport but the Kingdom has sought to expand its public transportation network in recent years. The King Abdulaziz Public Transport project is a major initiative to modernise transportation in the city of Riyadh. The capital is set to become the second city in Saudi Arabia with a metro network after the Makkah metro opened in 2010 (Saudi Gazette, 2020). Following a delay, the Riyadh metro system is set to open to passengers at the end of 2024 (Railway Technology, 2023; The M Metro Rail Guy, 2024).

The Saudi government has also taken steps to invest in rail transport; however, it remains unclear whether the new networks will be electric or diesel-powered. In 2010, it launched the Saudi Railway Master Plan, aiming to construct a 9,900-km network by 2040 (Oxford Business Group, 2020). The first phase, running until 2025, includes constructing and upgrading 5,500 km of tracks for freight and passenger transport, including interlinkages to the wider Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) railway network. The light rail network in the smart city NEOM is complete as of 2024 (Godfrey, 2024).

Electric vehicles

Saudi Arabia has taken steps to develop its own electric vehicle (EV) industry. As part of its “Vision 2030” strategy, the government aims to produce 50,000 EVs annually by 2030 and for 30% of Riyadh’s vehicles to be electric by 2030 (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2021c).

In 2022, Saudi Arabia introduced its first domestic brand of EV called Ceer, through a joint venture between PIF and Taiwanese car manufacturer Foxxconn (Al Arabiya News, 2023a). Manufacturing facilities for Ceer vehicles are under construction and expected to be operational by 2025 (Al Jazeera, 2023). Additionally, in June 2023, Saudi Arabia signed a USD 6 bn deal with Chinese EV manufacturer Human Horizons to collaborate on the development, manufacture, and sale of electric vehicles (Reuters, 2023).

To further promote the use of EVs, by 2024 the government had built 2,800 EV charging points,, with plans to set up 30,000 new stations by 2030 (Mobility Foresights, 2024).

Despite the progress made, achieving Saudi Arabia’s 2030 EV target will be challenging. The government will need to accelerate the deployment of charging infrastructure and introduce incentives to promote greater EV adoption (Apricum, 2022).

Buildings

In Saudi Arabia, per capita emissions in the buildings sector remain above regional and world average, despite a slow decline in recent years (Climate Transparency, 2022).

In 2012, the Saudi Energy Efficiency Center (SEEC) launched the Saudi Energy Efficiency Program (SEEP), which targets key sectors of the country’s economy (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2022). Through this program, SEEC has introduced a series of measures in the building sector, including mandatory labelling for insulation materials and air conditioners (Acs). SEEC has also developed guidelines designed to optimise energy consumption in buildings, with a focus on Acs, washing machines, refrigerators, lighting, and heaters. Since their introduction, these standards and guidelines have been further refined and continue to be enforced.

Saudi Arabia is taking steps to improve energy efficiency in buildings. Through the national Energy Services Company, TARSHID, the government aims to renovate numerous government buildings, public schools, hospitals, and mosques throughout the country (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2021b). Efforts are also underway to develop and implement an Energy Use Intensity (EUI) ecosystem (Saudi Arabia, 2024).

Land use and forestry

In 2012, the latest year for which national data is available, the land use and forestry sink only stood at 9 MtCO2e (UNFCCC, 2020), with forests covering a mere 0.5% of Saudi Arabia’s total land area in 2021 (World Bank, 2023). The government has announced plans to plant 450 million trees by 2030 and 10 billion trees over the coming decades as part of the Saudi Green Initiative. According to the government, this initiative foresees afforestation and land restoration measures increase the Kingdom’s forestry sink to 200 MtCO2e by 2030. Yet progress has been slow: by the end of 2023, Saudi Arabia had reportedly planted 44 million trees (Saudi & Middle East Green Initiatives, 2023).

Methane

In 2022, the methane sector accounted for 10% of total GHGs, the majority coming from the waste and energy sectors (Gütschow et al., 2024).

At COP26, Saudi Arabia signed the Global Methane Pledge, in which signatories agreed to cut methane emissions in all sectors by 30% globally over the next decade. While its 2021 NDC does not have explicit emission reduction targets for non-CO2 gases, it includes several measures to manage methane emissions, such as the objective to achieve zero flaring in the oil and gas industry (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2021b). However, Saudi Arabia is still planning to ramp-up its oil production capacity towards the end of the decade, making it in practice difficult to reduce its methane emissions.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter