Policies & action

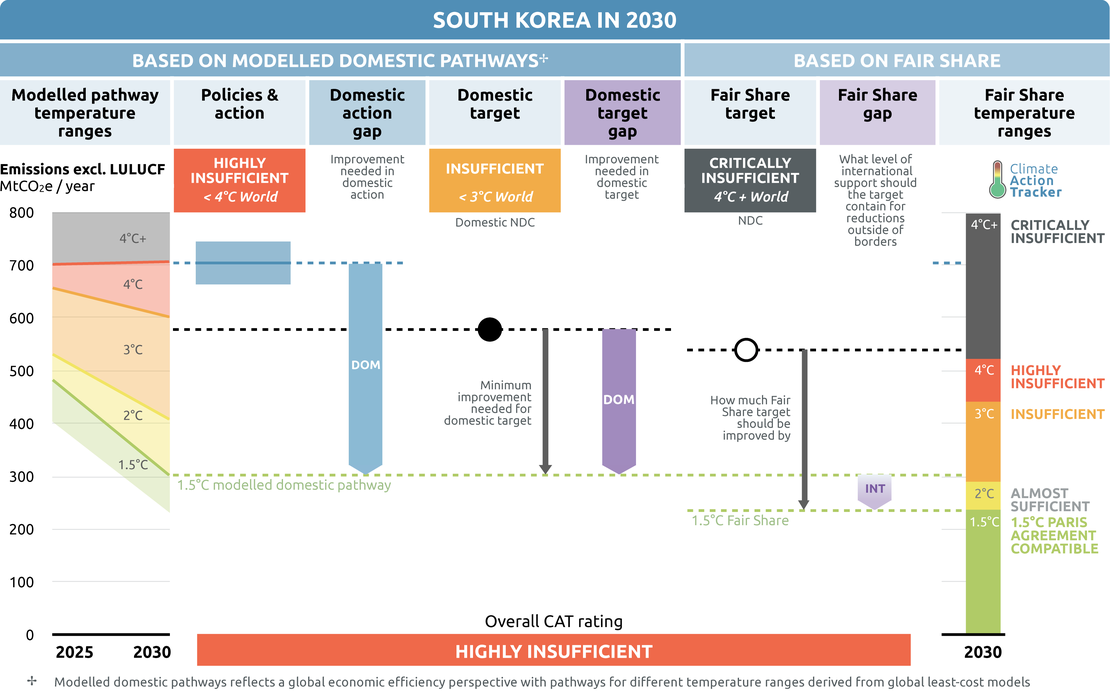

We rate South Korea’s policies and action as “Highly insufficient”. The “Highly insufficient” rating indicates that South Korea’s policies and action in 2030 are not at all consistent with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C temperature limit. If all countries were to follow South Korea’s approach, warming could reach over 3°C and up to 4°C. The range of projections under current policies spans two rating categories, with the median of the scenarios just about falling in the “Highly insufficient” range. A small upward change in the scenarios would result in a downgrade to “Critically insufficient” of South Korea’s policies and action.

The assessment below has not been updated and shows the status of the last update: 30 July 2020.

Currently implemented policies are estimated to lead to emissions levels of 665-743 MtCO2e/year in 2030 (‑7% to +4% relative to 2017 levels, 123% to 150% above 1990 levels) depending on the eventual impact of the COVID-19 crisis, and excluding emissions from land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF).

For the power sector, the impact of the Eighth Electricity Plan is not quantified in CAT’s analysis of South Korea’s current policy projections, due to the lack of laws or measures to implement them. The CAT estimates that if fully implemented (and taking into account the expected lower level of electricity demand highlighted above), these announcements would lead to about 20% reduction in electricity-related emissions below the upper bound projections of the current policies scenario in 2030 (see our December 2019 update) and result in similar emission levels as the lower bound projections of the current policies scenario.

The Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS), which replaced a previous feed-in tariff scheme and has been in place since 2012, is the main policy instrument to promote renewable energy. The RPS scheme requires major electric utilities to increase their renewable and “new energy” share in the electricity mix to 10% by 2023 (Korea New and Renewable Energy Center, 2019). Our current policies scenario projections on renewable electricity are modest partly due to this unambitious RPS.

One of the main cross-sectoral policy instruments implemented to date is the Korea Emissions Trading Scheme launched in 2015 (ICAP, 2019b). The ETS cap for Phase II (2018–2020) was announced in July 2018 and is set to increase from 1,686 CO2e in Phase I (2015–2017) to 1,796 CO2e in Phase II.

In the transport sector, the number of annual electric vehicles (EVs) sales doubled from 2017 to 2018 to 33,000, accounting for over 2% of total new car sales in 2018 (IEA, 2019b). The South Korean Government is pushing the uptake of EVs through subsidies and tax rebates (IEA, 2019b), with the goal of having 430,000 EVs on the road by 2022. The government is also investing in a programme to improve charging infrastructure.

On 14 July 2020 President Moon Jae-In announced a “New Deal” to the tune of KRW 160 trillion (USD 130 billion; including private and local government spending) (Cheong Wa Dae, 2020). The announced New Deal contained a KRW 42.7 trillion (USD 35 billion) plan to boost renewable energy deployment and low-carbon infrastructure, including support to put 1.13 million electric vehicles and 200,000 hydrogen vehicles on the roads by 2025 (Shin and Cha, 2020).

However, the New Deal did not deliver what the ruling party promised during the general election campaign: no net zero emissions target by 2050, no carbon tax and no commitment to end financing coal power plants overseas. The South Korean government also did not commit to a phase-out timeline for internal combustion vehicles.

Policy overview

Between 1990 and 2014, South Korea's emissions more than doubled. Emissions steeply increased in the early 1990s, with growth then continuing at a slower pace, and the CAT projects that GHG emissions growth will continue to slow. Actual emissions levels in the period 2010–2014 were above the BAU projections from the Third National Communication.

South Korea is one of the countries with the fastest growing emissions in the OECD. The high export rates from South Korea’s manufacturing industry play a critical role in South Korea’s increasing emission levels (Kim et al., 2015). In other developed economies such as the US, Australia or Canada, energy consumption per capita is projected to decline as economies shift towards the service sector and improve energy efficiency. However, South Korea is an exception: energy per capita is expected to continue to rise as industrial energy use increases and population declines (APERC, 2019; UN DESA, 2019).

Currently implemented policies are estimated to lead to an emissions level of 665 to 743 MtCO2e/year in 2030 (-7% to 4% in relative to 2017 levels, that is 123% to 150% above 1990 levels) depending on the eventual impact of the COVID-19 crisis, excluding emissions from land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF). South Korea currently commits, in its NDC, to achieve 539 MtCO2e/year excluding LULUCF (81% above 1990 emission levels). To reach this target, South Korea will have to significantly strengthen its climate policies, even more so if the country really wants to carbon neutrality by 2050.

One of the main cross-sectoral policy instruments implemented to date is the Korea Emissions Trading Scheme launched in 2015 (ICAP, 2019b). To reduce sectoral emissions, South Korea introduced the GHG and Energy Target Management System (TMS) in 2012, a precursor to the Emissions Trading System (ETS) and which covered 60% of total emissions. The TMS still covers emitters consuming significant amounts of energy that are not covered by the ETS. As a result of TMS operations, 65 companies collectively reduced their emissions by 0.74 MtCO2e/year in 2015 compared to business-as-usual, equating to just over 0.1% of national total emissions (Republic of Korea, 2016a).

The ETS covers 68% of national GHG emissions and nearly 600 companies from 23 sub-sectors (ICAP, 2019b) from steel, cement, petrochemicals, refinery, power, buildings, waste and aviation sectors. This includes all installations in the industrial and power sectors with annual emissions higher than 25 ktCO2e. The ETS system includes both direct and indirect emissions (emissions from electricity use).

The ETS cap for Phase II (2018–2020) was announced in July 2018 and is set to increase from 1,686 CO2e in Phase I (2015–2017) to 1,796 CO2e in Phase II. In this phase, 97% of the allowances is allocated for free and the remaining 3% will be auctioned. For Phase III (2021–2025), more than 10% of allowances are set to be auctioned (ICAP, 2019b). For comparison, 57% of the allowances will be auctioned over the current phase (Phase III: 2013–2020) of the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) (ICAP, 2019a).

In the revised 2030 GHG roadmap, South Korea provides details on sector-specific reduction targets as well as policy measures to be further encouraged. For the building sector, the plan mentions strengthening permit standards for new buildings, promoting green renovation, identifying new circular business models, and expanding renewable energy supply. For the industry sector, the plan focuses on energy efficiency and industrial process improvement measures but also on the promotion of eco-friendly raw materials and fuel (Ministry of Environment, 2018). These planned measures are not considered in our current policy projections.

Energy supply

In 2017, the electricity and heat sector represented 54% of national CO2 emissions from fuel combustion. South Korea’s power generation increased fivefold over the period 1990–2017 and is dominated by coal-fired (45% in 2017) and nuclear generation (26% in 2017) (IEA, 2019a). The average CO2 emissions factor of electricity generation has made little progress since 1990 and renewable electricity share is notably lower than the EU, Japan and the US (see Figure below).

Motivated by air pollution, concerns over safety of nuclear power plants and climate change, President Moon Jae-In intends to reverse the policy direction of his predecessors by reducing reliance on nuclear and coal-fired power and increasing the share of renewable electricity.

The two framework policies for the energy supply sector are the third Energy Master Plan adopted in June 2019 for the period up to 2040 (MOTIE, 2019a) and the eighth 15-year Plan for Electricity Supply and Demand ( “the eighth Electricity Plan”) adopted in December 2017 for the period up to 2030 (MOTIE, 2017). The third Energy Master Plan has supposedly been developed in concert with the eighth Electricity Plan. As part of the country’s effort to tackle air pollution, the Government announced in November 2019 to retire six older coal-fired power plants by 2021, one year earlier than the initial plan (Reuters, 2019).

The third Energy Master Plan aims to increase the renewable electricity share to 20% by 2030, and 30–35% by 2040 - up from 3% in 2017 (IEA, 2019c) mainly by increasing the total renewable power capacity up to 129 GW. In contrast, the new Energy Master Plan neither sets targets for reducing the share of coal and nuclear power, nor a timeline for the phase-out of coal-fired power plants.

For 2030, the eighth Electricity Plan adopted in December 2017 set clear electricity mix targets, which confirmed the Moon administration’s intention to shift electricity generation away from coal and nuclear towards more renewables (Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, 2017a).

The eighth Electricity Plan would result in an electricity generation mix in 2030 based on 23.9% nuclear, 36.1% coal, 18.8% natural gas and 20% renewable energy (Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, 2017a). The significant difference with previous targets comes from the drop in natural gas-based generation (27% in a May, 2017 announcement) that is mostly compensated by the share of coal-based generation remaining very high.

The eighth Electricity Plan also projected electricity capacity would peak in 2030 at 100.5 GW, 11% lower than the previous 2015 edition of the plan. The current power capacity surplus (generated by recently built coal-fired power plants) provides headroom for a rapid build-out of renewable energy generation (Webb and Kim, 2018) that also represents an opportunity for Korean companies to expand into the renewables market.

The plan also revised the estimated electricity demand for 2030 from 657 TWh (as defined in 2015) to 579.5 TWh (MOTIE, 2017). The CAT concludes, based on the assessment of recently published studies (Keramidas et al., 2018; APERC, 2019; Wood Mackenzie, 2019), that South Korea will remain short of reaching its targeted 20% renewable energy share by 2030.

The CAT does not quantify the impact of the eighth Electricity Plan in our analysis of South Korea’s current policy projections, due to the lack of laws or measures to implement it. Our December 2019 update estimated that if fully implemented (and taking into account the expected lower level of electricity demand highlighted above), these announcements would lead to about 20% reduction in electricity-related emissions in 2030. This would result in a national total emissions level similar to the lower bound of the current policies scenario projection. The ninth Electricity Plan is currently under development; the draft plan calls for increasing the renewable electricity share to 40% by 2034 among other targets, which would be a major step forward towards decarbonisation of the South Korean power sector (Yonhap News Agency, 2020).

In terms of research and development of advanced technologies, the roadmap for hydrogen economy published in January 2019 (MOTIE, 2019b) sets a goal of increasing the cumulative domestic fuel cell production volume (not the power generation capacity) from 308MW in 2018 to 15GW by 2040.

With regard to specific policy instruments to support renewables, the Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS), which replaced a previous feed-in tariff scheme, has been in place since 2012. The RPS scheme requires the 13 major electric utilities to meet annual generation targets from renewable and new energy, with the objective to increase renewable and “new energy” share to 10% in 2023 (Korea New and Renewable Energy Center, 2019). “New energy” technologies include fossil fuel-based technologies such as coal-fired Integrated Gasification Combined Cycle (IGCC) plants. Given its current status of technological development and global deployment, IGCC is likely to play a very minor role in future electricity generation. Our current policies scenario projections on renewable electricity are modest partly due to this unambitious RPS.

All these policies and policy plans in place in the power sector are far from being consistent with 1.5 °C-consistent pathway, under which coal-fired power must be phased out by 2029. South Korea could aim for a renewable energy share of more than 50% in 2030, particularly given a number of studies demonstrate that South Korea could achieve high shares of renewable energy, including reaching close to 100% by 2050. (Climate Analytics, 2020). Our current policies scenario (pre-COVID) projects a coal-fired power generation share of 28% to 38% and a renewable energy share of 8% to 17% in 2030.

Transport

In 2017, the transport sector represented 17% of national CO2 emissions from fuel combustion (IEA, 2019a).

South Korea is the world’s fifth largest car manufacturing country (OICA, 2019) with major companies such as Hyundai and Kia headquartered there. In 2014, South Korea strengthened its light-duty vehicle emissions standard to 97 gCO2/km by 2020 (Transportpolicy.net, 2019), which is comparable to the EU’s new standards (95 gCO2/km) (ICCT, 2019).

The number of annual electric vehicles (EVs) sales doubled to 33,000 from 2017 to 2018, accounting for over 2% of total new car sales in 2018 (IEA, 2019b). The South Korean Government is pushing the uptake of EVs, with a goal of having 430,000 EVs on the road by 2022 through subsidies and tax rebates (IEA, 2019b). The government is also investing in a programme to improve charging infrastructure (ibid.)

Based on the recently adopted revised 2030 GHG roadmap, South Korea intends to expand the supply of eco-friendly vehicles (including the supply of 3 million electric vehicles in 2030) (Ministry of Environment, 2018). The Korean Government also announced in January 2019 a roadmap for hydrogen economy, which sets goals of producing 6.2 million fuel cell electric vehicles and building 1,200 fuelling stations across the country by 2040 (MOTIE, 2019b).

Buildings

In 2017, the buildings sector represented 9% of national CO2 emissions from fuel combustion (aggregate of residential and commercial sectors) (IEA, 2019a). When indirect emissions from electricity consumption are taken into account, the sector’s share increases to 32% (IEA, 2019a, 2020). South Korea is gradually applying stricter energy conservation designs to meet zero-energy buildings standards for all new buildings by 2025 (APERC, 2019).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter