Policies & action

The CAT rates South Korea’s current policies as “Insufficient”. The rating indicates that South Korea’s climate policies and action in 2030 need substantial improvements to be consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C. If all countries were to follow South Korea’s approach, warming would reach over 2°C and up to 3°C.

The policies and action rating has changed from “Highly Insufficient” to “Insufficient” compared to the 2023 CAT assessment due to a methodological update of our modelled domestic pathways (MDPs[1]), which now also incorporate the latest global least-cost pathways from the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report. This change in rating does not necessarily represent a meaningful improvement in climate action on the ground compared to our previous assessment. In fact, the upper end of South Korea’s projected emissions under current policies has increased following a considerable upwards revision in historical data and updated projections from the government.

South Korea’s emissions under current policies will reach between 638–701 MtCO2e/year in 2030, or 11–19% (excl. LULUCF) below 2018 levels in 2030, falling well short of reaching its domestic (i.e. excluding international credits) 2030 NDC target of 32% below 2018 levels. The upper end of South Korea’s projected emissions under current policies has increased following a considerable upwards revision in historical data and updated projections from the government. In particular, the industrial sector, South Korea’s largest energy consumer, could hinder emissions reduction efforts. This underscores the need for the South Korean government to ramp up implementation to close the gap between its current policies and NDC target and align with a 1.5°C-compatible trajectory.

Compared to the 10th Plan, the 11th Basic Plan for Electricity Supply and Demand, finalised in February 2025 under the Yoon administration, depicts a greater reliance on fossil gas, a slight reduction in coal, and maintains nuclear power as the dominant source of electricity generation at 32%. At the same time, it keeps the targeted share of renewable energy the same at 22% in 2030. This underscores the need for the Korean government to ramp up implementation to be able to close the gap between its current policies and NDC target, and to align with a 1.5°C-compatible trajectory.

Prior to his impeachment, former president Yoon Suk-Yeol pursued a nuclear-focused strategy, approving two large scale nuclear projects in 2024 which were denied by the Moon administration following its denuclearisation policy. While the draft 11th Plan had proposed three new large reactors, the final plan scales this back to two, reflecting a slight increase in planned renewable energy capacity. Yoon also approved an offshore drilling project led by the Korea National Oil Corporation (KNOC), targeting potential reserves of up to 14 billion barrels of oil and gas. Although KNOC stepped back from further drilling after early results showed limited commercial potential, it is still seeking external investors to help advance future exploration efforts. As one of the world’s largest importers of oil and gas, South Korea should prioritise renewable energy development to avoid technology lock-in and risks of stranded assets rather than expand fossil fuel production.

South Korea’s energy policy has continued to shift across administrations, although these developments are not yet reflected in our current policy projections. Since he was elected in June 2025, President Lee Jae-Myung and his Democratic Party have made decisions which appear to signal a positive change toward more climate action: announcing a coal phase-out date and joining the powering Past Coal Alliance, along with agreeing on a new 2035 headline target, and adapting Phase 4 of the Emissions Trading Scheme to better meet its 2030 target, and making more positive statements about renewables.

While South Korea’s coal phase-out announcement represents a considerable step towards decarbonising the power sector, the planned pace is insufficient for near-term climate goals, and the role of fossil gas/LNG as a transition fuel raises questions about the overall impact.

Further information on how the CAT rates countries (against modelled domestic pathways and fair share) can be found here.

[1] The changes to our modelled domestic pathways are particularly significant for South Korea. These result from updating our global least-cost pathways from the IPCC's Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels (SR1.5) to the Sixth Assessment Report (AR6). SR1.5 consisted of only five regions (R5ASIA/LAM/REF/OECD/MAF, with South Korea grouped under R5ASIA). The AR6 expanded the regional resolution to provide 10 regions, and ASIA was split into CHINA, INDIA and REST_OF_ASIA (with South Korea grouped under REST_OF_ASIA). While grouped in R5ASIA, South Korea's emissions allowance was influenced by strong trends of rapidly falling emissions (specially from China). When the added regional resolution separates China and India from the rest of Asia, South Korea is grouped with developing countries where emissions could still slightly grow, therefore resulting in a higher emissions allowance than before.

Policy overview

Under current policies, the CAT estimates that South Korea’s 2030 greenhouse gas emissions projections span a wider range compared to the 2023 CAT update, while the average has remained broadly unchanged. The government has upwardly revised historical emissions data, at about a range of 40 Mt per year, due to previously unaccounted-for coal consumption from private power plants, and reported emissions from industrial F-gases appear to have considerably increased. New government projections also anticipate rising emissions in the future, particularly in the industrial sector. Our current policy projections do not consider the potential impact of the newly announced coal phase-out on emissions. See more detailed assumptions here.

The CAT projects that South Korea’s policies will lead to an emissions level of 638–701 MtCO2e/year in 2030 (11% to 19% below 2018 levels) (excl. LULUCF). This leaves a gap of 134–197 MtCO2e to meet South Korea’s domestic climate target, and even deeper reductions are required to reach an emissions level of 459 MtCO2e by 2030, compatible with the CAT’s 1.5°C MDP trajectory.

The political changes in South Korea have led to a shift in climate and energy policy. Former President Yoon Suk-yeol, who took office in 2022 and was then impeached in 2024, moved away from his predecessor’s denuclearisation policies and reversed them. After being on hold since 2017, the Yoon administration granted approval for the development of two nuclear power plants (1.4 GW each) in 2024, which are scheduled to be fully constructed between by 2038 (Agence France-Presse, 2024).

South Korea has 26 nuclear reactors operating (IAEA, 2024; KEEi, 2024). The 11th Plan includes the construction of two new large-scale nuclear reactors (up to 2.8 GW) and an SMR (0.7 GW) by 2038 to meet rising energy demand while cutting emissions. One of the initially proposed units in the draft plan was omitted from the final version due to opposition parties in the National Assembly pushing for a larger share of renewables, with slightly higher capacity and generation targets (Kim, 2025).

Although nuclear electricity generation does not emit CO2, the CAT doesn’t see nuclear as the solution to the climate crisis due to several risks such as nuclear accidents and proliferation, high and increasing costs compared to renewable alternatives, long construction times, incompatibility with the flexible supply of electricity from wind and solar, and its vulnerability to heat waves. The previous government’s shift in focusing funding on nuclear power risks causing renewables development to stagnate (Enerdata, 2023; IEEFA, 2024).

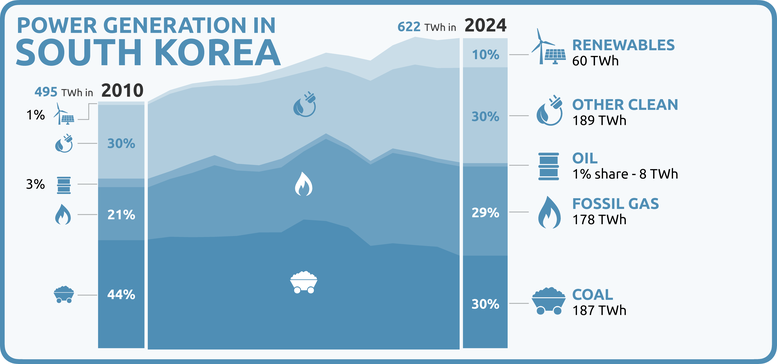

South Korea’s renewable energy development continues to lag behind both national and global targets. In 2024, renewables accounted for only 10% of electricity generation (Ember, 2025). The 10th Basic Plan updated the renewable target to 22% by 2030 and 31% by 2036, falling short of the 30% target in the updated 2030 NDC. The 11th Basic Plan depicts a similarly slow uptake of renewables, reaching only 33% by 2038.

The development of renewable energy projects has faced roadblocks such as infrastructure gaps, regulations and grid limitations, which have contributed to industry and public reluctance towards renewable energy. While the new government under President Lee Jae-Myung has expressed support for expanding renewable energy development and targets, it remains to be seen how quickly and effectively these it will implement these ambitions. The recent coal phase-out commitment, joining of the Power Past Coal Alliance, and Emissions Trading Scheme reform suggest a potential shift toward stronger climate action.

At COP30, South Korea announced a commitment to phase out its unabated coal-fired power plants by 2040, with 40 out of its 61 plants already scheduled for retirement (PPCA, 2025). While this marks a concrete step towards power sector decarbonisation, this timeline is insufficient to align with near-term climate goals. In the interim, fossil gas is expected to remain a major part of the electricity mix, as the government plans to convert several retiring coal plants to LNG.

The coal phase-out will leave an estimated 40 GW of capacity requiring replacement (Argus Media, 2025). The South Korean government’s approach on transitioning away from coal through LNG is counterproductive towards the 1.5°C temperature goal. To ensure the coal phase-out leads to real emissions reductions, South Korea will need to speed up renewable energy deployment to meet future energy demand.

In November 2025, South Korea finalised the allocation plan for Phase 4 of its nationwide Emissions Trading Scheme (K-ETS), covering 2026–2030, alongside its updated 2035 climate target. The plan tightens the overall emissions cap and increases the share of allowances that companies must purchase rather than receive for free, although it maintains free allocations for many high-emitting industrial sectors in recognition of competitiveness concerns. These reforms are intended to help align the ETS with the country’s 2030 NDC, but their effectiveness will depend on how the scheme is implemented and how companies respond to the tighter rules (ICAP, 2025).

Other policy developments

In line with the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol, the government enforced the Ozone Layer Protection Act in April 2023, aiming for a gradual phase-down of the consumption and production of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) (IIR, 2023). In South Korea, HFCs and hydro chlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) are widely used for air cooling, refrigerators and freezers. In December 2024, the government announced a target to reduce HFCs by 20 million tonnes below a 61 million ton baseline by 2035, with the implementation phase set to begin in 2027 (Min-hee, 2024).

At COP28, South Korea introduced the "Carbon Free Alliance", a public-private initiative involving major South Korean corporations such as Hyundai, Samsung, and state-owned firms such as the Korea Electric Power Corporation (KEPCO), Korea Hydro and Nuclear Power, and the Korea Energy Agency. The initiative is aimed at promoting the diversification of energy sources and expanding carbon-free energy, with a focus on hydrogen, nuclear and renewables to help achieve carbon neutrality. The initiative, however, faced challenges in attracting global participation due to concerns over its credibility (Dong-hwan, 2023).

Electric vehicle adoption in South Korea is still growing overall, with EVs comprising 9.3% of total sales in 2023. This figure represents a slight decline from the 9.7% recorded in 2022, in part due to increasing concerns about insufficient charging infrastructure, rising prices, and safety issues (The Chosun Daily, 2024; The Korea Herald, 2024).

The government aims to capture 12% of the global electric vehicle market by 2030. It has shown huge support for the EV industry through tax incentives, subsidies, expanding charging station instalment and support in production facilities and R&D, but its growth will likely be impacted by external factors such as US tariffs on exports. During his presidential campaign, Yoon had pledged to ban the new registration of combustion-engine vehicle in 2035, but did not follow through with an explicit commitment (Climate Transparency, 2022; The Korea Bizwire, 2022).

The government has established its domestic ESG regulatory framework to improve corporate sustainability efforts and deter greenwashing. In 2022, the government laid out K-ESG guidelines to establish standards for corporate sustainability (Invest Korea, 2022; MOTIE, 2022). To strengthen the country’s response to the changing ESG landscape, the Private-Public Joint ESG Policy Council was launched in 2023.

The government also plans to introduce a mandatory ESG disclosure system for listed companies with assets exceeding KRW 2 tn (USD 1.4bn). Although initially set for 2025, the implementation of the system has been delayed until after 2026. To finance projects aimed at shifting to low-carbon production, the government pledged to allocate up to KRW 420 tn (USD 313.4 bn) in policy loans from the state budget by 2030 (Financial Services Commission, 2024). On top of that, the Korean Development Bank, alongside five big Korean banks, plans to establish a “future energy fund” amounting to KRW 9 trillion (USD 6.26bn) until 2030, dedicated for clean energy investment. The plan also includes mobilising additional green finance to support renewable energy projects and the development of climate technologies (Ministry of Climate, Energy and Environment, 2024). However, there is limited information on specific measures to boost participation in the programme and the compliance mechanisms involved.

Power sector

In 2024, South Korea’s electricity supply was predominantly sourced from coal (30.5%), natural gas (28.5%) and nuclear (30%) and renewables (10%) (Ember, 2025). The power sector accounted for over half of energy-related CO2 emissions in 2023 (IEA & KEEi, 2022).

South Korea’s energy policy has continued to shift as different administrations come into power. Before his impeachment, former president Yoon Suk-Yeol envisioned a prominent share of nuclear in the country’s energy mix, reversing the nuclear phase-out policies set by his predecessor and rolling back the renewables target outlined in South Korea’s 2030 NDC. However, this nuclear-focused direction may be challenged by the newly elected parliament by Yoon’s successor. The victorious Democratic Party and President Lee Jae-Myung hold differing views on both nuclear and renewable energy, suggesting South Korea’s energy strategy may shift again (Daul, 2024; Yu & Roh, 2024).

Every two years, South Korea releases a Basic Plan for Electricity Supply and Demand, outlining the government’s strategy for managing electricity needs for the next 15 years. The government approved the 11th Basic Electricity Plan in February 2025. The plan sets the share of nuclear in the electricity mix to reach 32% in 2030 and up to 36% by 2038, exceeding the 24% target initially planned in the NDC. In contrast, the share of renewables in the electricity mix is projected at 22% by 2030, falling short of the 30% target in the 2030 NDC, and 33% by 2038 (Kim, 2025).

South Korea’s Emissions Trading Scheme (K-ETS) enters Phase 4 in 2026, with a tighter overall emissions cap intended to align with its 2030 target and a new linear reduction factor differentiated between the power and non-power sectors. The allocation plan also embeds sector-specific reduction trajectories, targeting a 69–75% reduction in emissions in the electricity sector (compared to 2018 levels) by 2035, although its effectiveness will depend on how the sector responds to the tighter rules and allowance requirements (ICAP, 2025).

At COP 30, South Korea took a concrete step towards power sector decarbonisation by joining the Powering Past Coal Alliance, committing to halt the construction of new unabated coal power plants and to phase out existing ones by 2040 (PPCA, 2025). Questions remain, however, about the role of LNG in the coal phase-out and the pace of other measures to expand renewable energy.

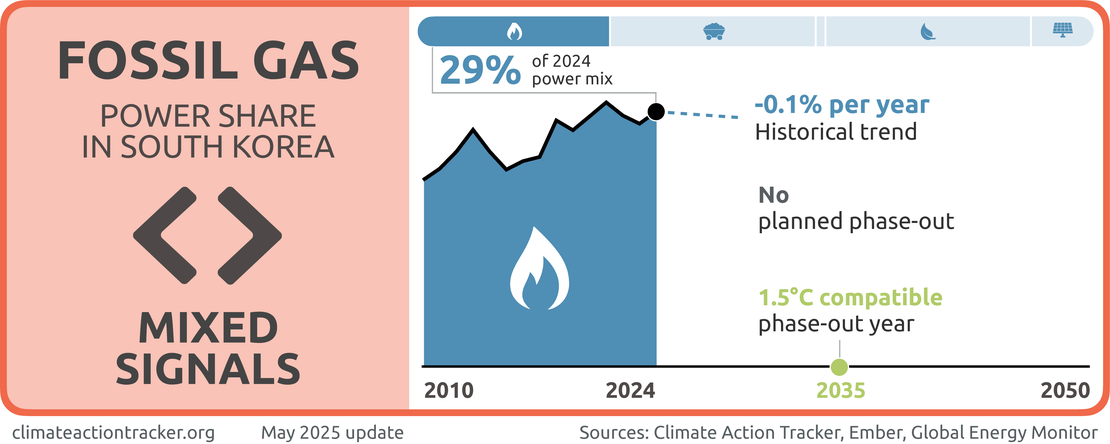

South Korea has no explicit commitment to phasing out fossil gas from the power sector. The government plans to produce hydrogen and ammonia power in their existing coal and LNG generators (MOTIE, 2024a). A recent study indicates that a 1.5°C-compatible pathway for South Korea would require power sector emissions to decrease by roughly 90% below 2022 level by 2030, ultimately reaching zero by 2034. Gas-fired power generation would need to drop by 60% within this decade, and be fully phased out from the power sector by 2034. There must be no room for new fossil gas after 2023, and coal-to-gas conversion is not compatible with a 2034 phase-out timeline (Climate Analytics, 2023).

A clean power system is possible for South Korea; it has enough renewables potential to shift away from fossil fuels to meet its future electricity demand. The current government’s reliance on LNG imports imposes risks on energy security, economic loss, and public health.

Coal

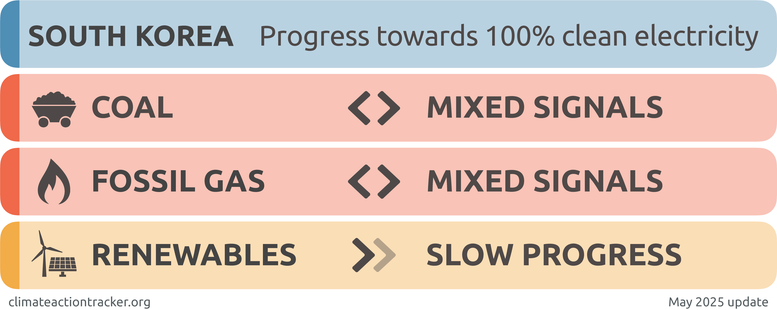

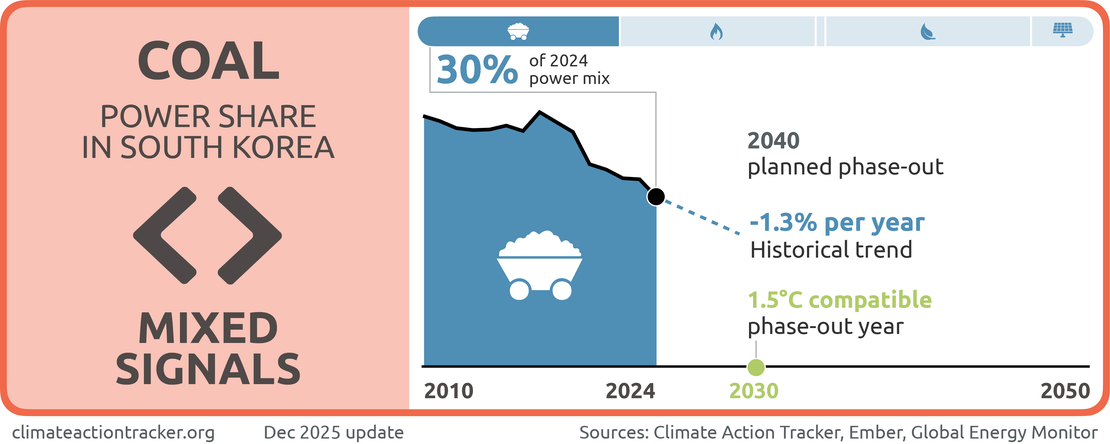

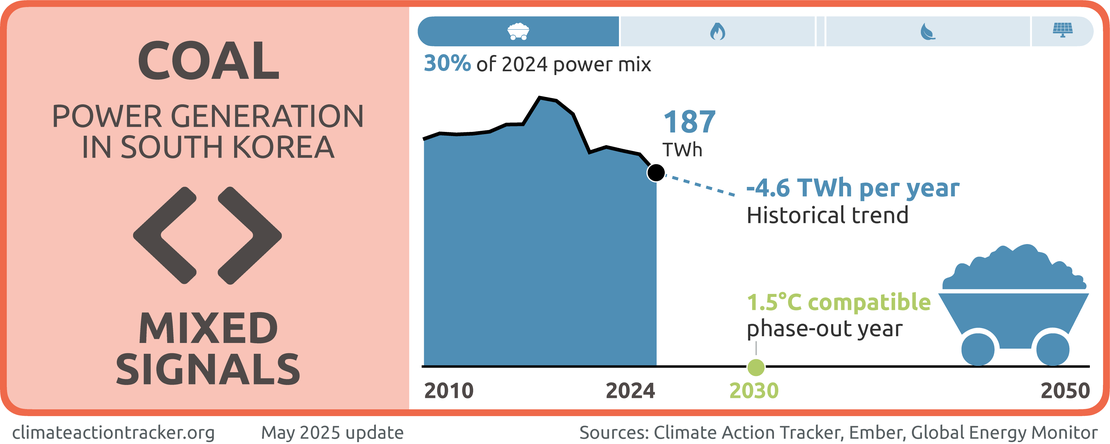

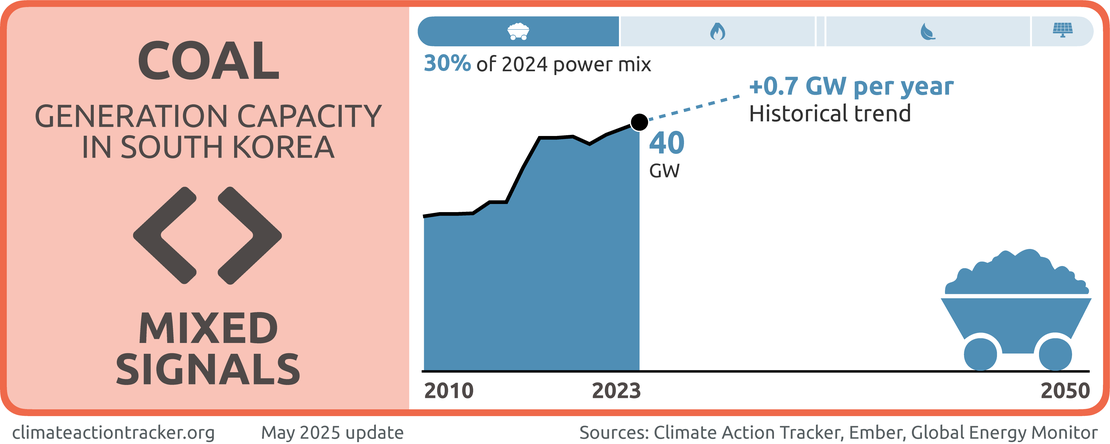

South Korea is sending “Mixed Signals” on coal.

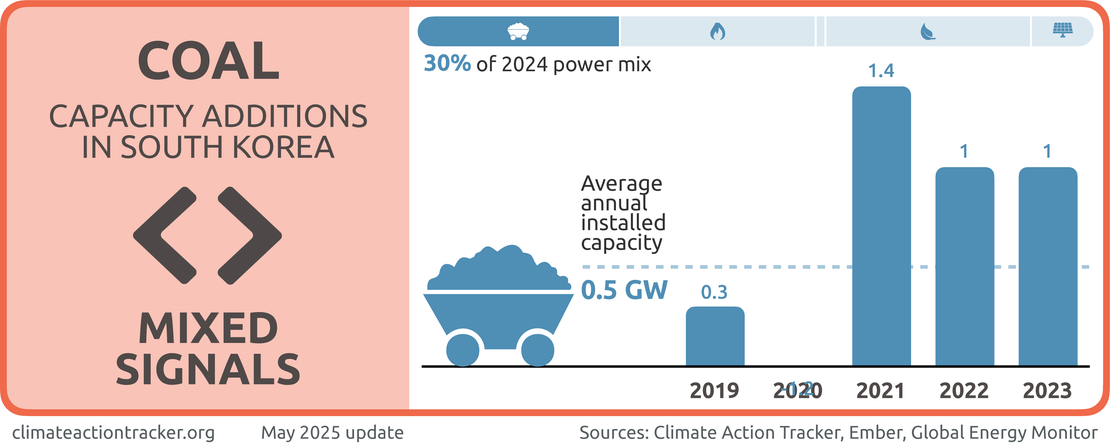

Although the share of coal in the power mix has steadily declined in the last five years, falling from 42% in 2019 to 30% in 2024, until recently, South Korea has continued to expand its coal capacity, with around 1.1 GW of coal projects remaining in the development pipeline (Ember, 2025; Global Energy Monitor, 2025).

At COP 30, however, the government joined the Powering Past Coal Alliance and announced its commitment to stop building new unabated coal power plants and to phase out existing and unabated plants. While 40 out of South Korea’s 61 existing coal power plants are confirmed to phase out by 2040, the phase out date for the remainder will be determined based on public discussions on economic and environmental feasibility (PPCA, 2025).

Coal has dominated South Korea’s electricity matrix. In 2024, total electricity generation from coal reached 191 TWh (around 30% of total generation) (Ember, 2025). According to the 11th Basic Electricity Plan, total power generation from coal will reach 111.9 TWh (17% of total) by 2030, lower than the target set in its 2030 NDC. By 2036, South Korea plans for coal to account for 72 TWh (10.3% share) of its power mix.

South Korea is among the world’s top five coal importers. While import volumes have been declining since 2018, resulting from a variety of reasons such as KEPCO restrictions on coal power generation, declining import volumes from Russia and Indonesia, and growing electricity generation from nuclear, the total magnitude of imports has increased by 73% in 2023 compared to 2000s volumes (Argus Media, 2021; Maguire, 2025).

The Ministry of Trade, Investment and Energy (MOTIE) plans to produce hydrogen and ammonia power in existing coal and LNG generators as part of the coal phase-out strategy. The government targeted commercialising at least 30% hydrogen co-firing by 2035 and a total coverage by 2040. The government also plans to apply 20% ammonia co-firing power generation over more than half of existing coal power plants (total 45 units) by 2030. A recent study warns that ammonia cofiring could risk several environmental hazards, including toxic gas and fine dust pollutions on top of the coal combustions related negative externalities (SFOC, 2024a).

According to a recent study, the cost of compensating operators for the early retirement of all coal plants that began operation after 2014 using public financing is expected to be KRW 1.8 tn (USD1.4bn) by 2035, with the cost of retirement by 2030 estimated to be KRW 6.6tn (USD 5bn) (SFOC, 2023). Concrete preparations to assist a just transition for coal industry workers are required in South Korea and globally.

South Korea has historically been a major donor of fossil fuel project overseas, estimated around USD 10bn per year (SFOC, 2024b). Fossil fuel projects account for 74% of the overseas energy portfolio of South Korea’s public finance agencies, mainly fossil gas (58%) and oil (16%) (SFOC & GESI, 2025). The Moon administration had intended to turn the tide against cross-border coal financing (White House, 2021). However, concerns emerged under the following Yoon administration about potential backpedalling. In the OECD negotiations in November 2024, South Korea, together with Türkiye, opposed the fossil fuel finance restriction, leading to a stalemate (SFOC, 2024b).

The policy direction of the current government under President Lee with respect to overseas fossil fuel finance has not yet been clearly articulated, highlighting the need for greater clarity on the government’s future approach to overseas fossil fuel finance.

Fossil gas

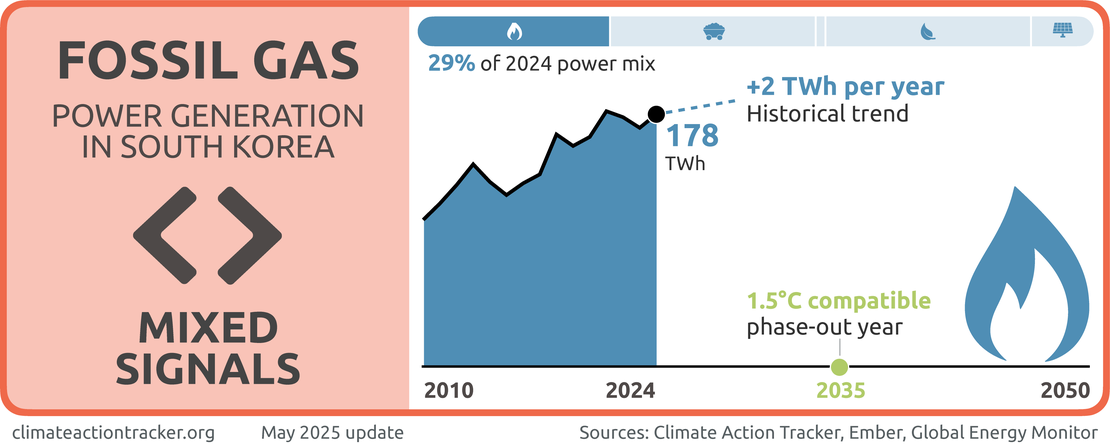

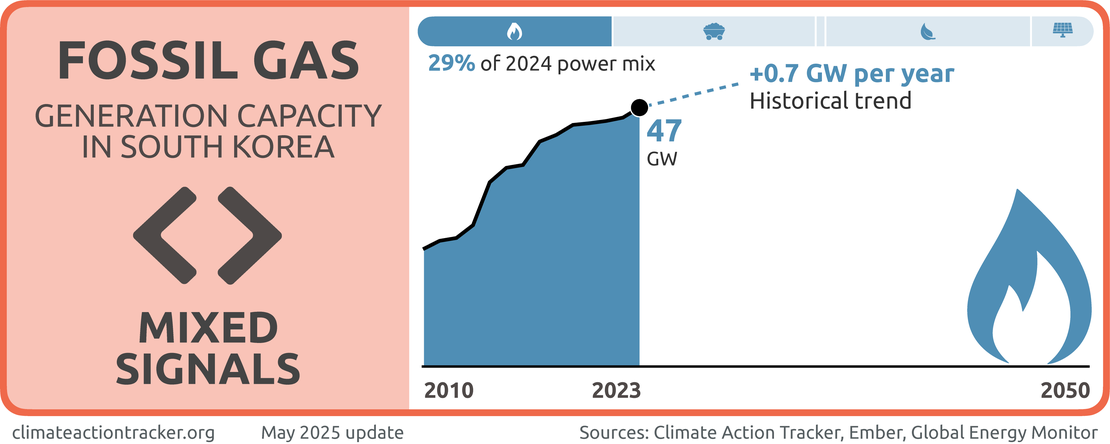

South Korea is also sending “Mixed signals” on fossil gas.

The share of fossil gas in South Korea’s electricity mix has remained stagnant in the last five years, with actual generation largely unchanged. However, the government is currently pursuing a coal-to-gas strategy that will significantly expand fossil gas capacity. In 2024 alone, 1.8 GW of new fossil gas capacity was installed, and a large pipeline of additional projects is currently under development (Ember, 2025; Global Energy Monitor, 2025).

Following South Korea’s recently announced coal phase-out commitment, it is critical that the transition does not involve replacing coal with expanding fossil gas infrastructure. LNG-fired power generation is expected to account for 21.6% of power generation in 2030, which reflects South Korea’s plan to convert 26 existing coal power plants (13.7 GW), expecting to reach the end of their operational life by 2036, to LNG. Five new LNG plants will be built to generate an additional 4.3 GW of electricity.

Recent studies argue that the South Korean government’s approach on transitioning away from coal through LNG will do little to help achieve the 1.5°C temperature goal. Fossil gas generation in South Korea must drop by 60% within 2022–2030, and be completely phased out by 2034 and as soon as 2031 to be aligned with a 1.5°C-compatible pathway (Climate Analytics, 2023).

Fossil gas was the third largest of electricity source in South Korea in 2023 (IEA, 2024b). The Korean Gas Corp. (KOGAS) imported 90% of its LNG, making the country the world's third largest LNG importer (EIA, 2023; ITA, 2020). Under the 11th Basic Electricity Plan, fossil gas is set to account for 25% and 11% of power generation in 2030 and 2036, respectively, a 2% increase in 2030 compared to the 10th Basic Electricity Plan.

In June 2024, then-President Yoon approved an exploratory drilling project off South Korea’s east coast, targeting potential reserves of up to 14 billion barrels of oil and gas and having committed over USD 363m to this project, with initial results expected in the first half of 2025. The government claims the project could generate enough fossil gas to power the country for 29 years and a sufficient amount of oil for four years, significantly reducing South Korea's reliance on imported LNG. Led by the Korea National Oil Corporation (KNOC), the current project aims for commercial production by 2035 and may involve drilling up to 10 wells, each costing approximately KRW 100 bn (Journal of Petroleum Technology, 2024; Park & Kim, 2024). Although KNOC stepped back from further drilling after early results showed limited commercial potential, it is still seeking external investors to help advance future exploration efforts.

In 2023, the government released its carbon neutrality roadmap, which put a notable emphasis on South Korea’s reliance on Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) as a key technology for mitigating GHG emissions (Ministry of Climate, Energy and Environment, 2023b). CCS technology is planned to be applied to all fossil-fuel and LNG power generation. The perpetuation of the fossil fuel industry could jeopardise the necessary efforts to pressure high-emitting industries to make a rapid transition to renewable energy sources.

CCS refers to technologies which use engineered methods to capture CO2 from a source and store it geologically. CCS can be applied to a range of different CO2 sources in different sectors. CCS technologies are neither commercially viable nor proven at scale, despite large public subsidies for research and development globally.

Heavily relying on unproven CCS for power generation simply prolongs the use of fossil fuels, diverting attention and resources away from the necessary and urgent switch to renewable energy generation that drives down actual emissions.

The use of CCS should be limited to industrial applications where there are fewer options to reduce process emissions—not to reduce emissions from the electricity sector where renewables are cost-effective mitigation alternatives, not least because CCS doesn't remove 100% of emissions from power plants.

Renewables

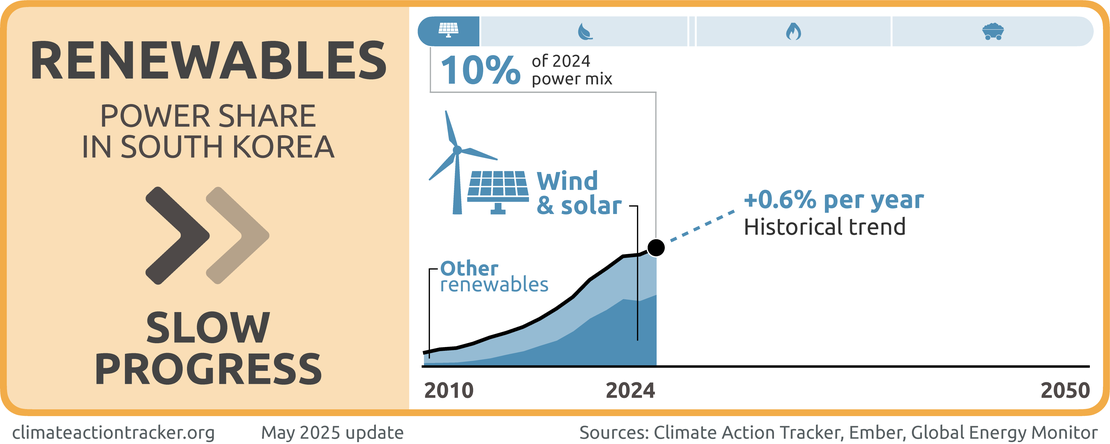

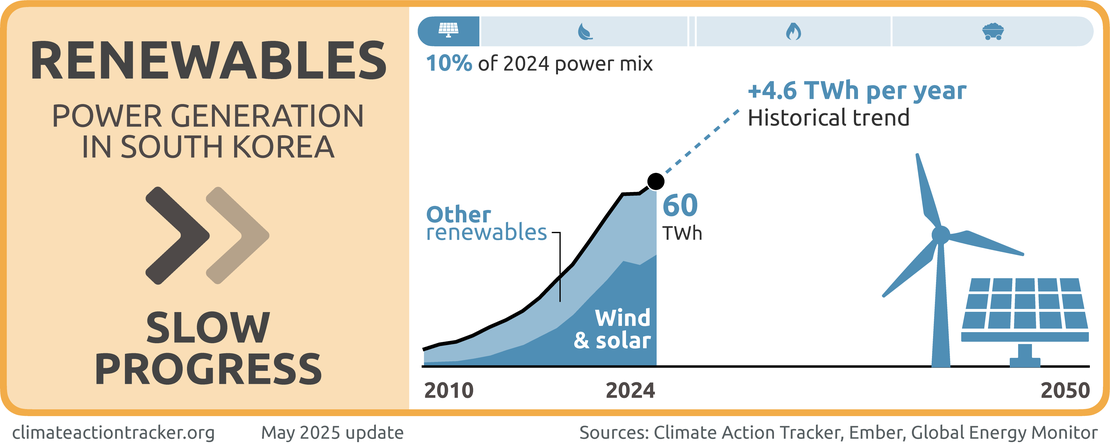

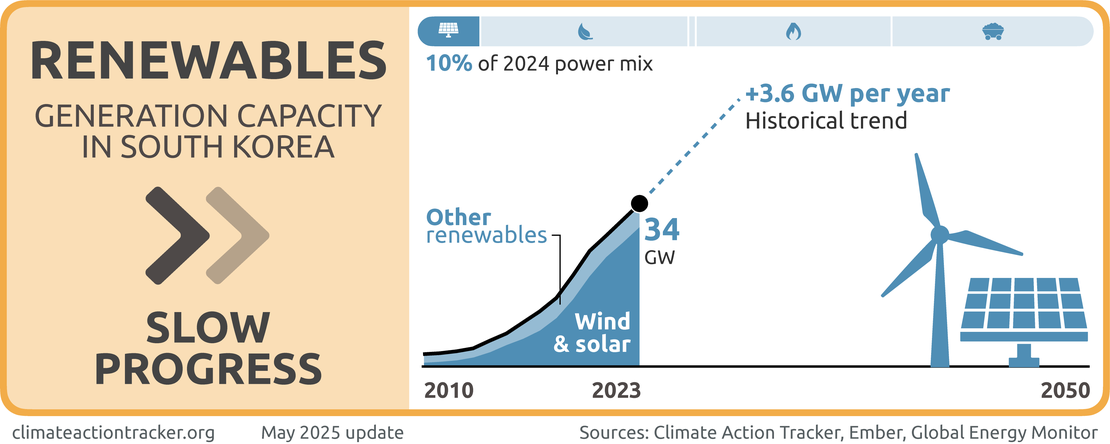

South Korea is making “Slow Progress” in deploying renewables.

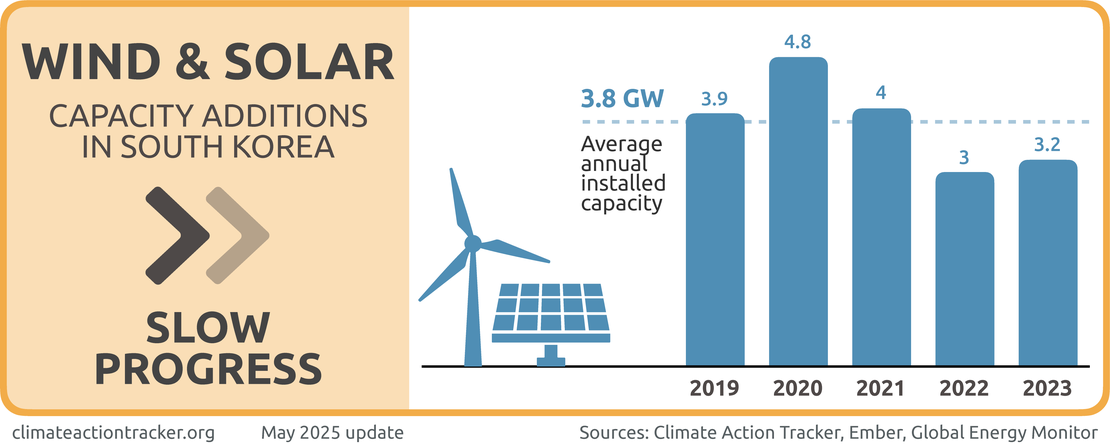

The share of renewables in the power mix has gradually increased in the last five years, rising from 6% in 2019 to 10% in 2024. South Korea continues to expand its renewable capacity, adding an average of 3.8 GW of wind and solar to the grid each year over this period (Ember, 2025; Global Energy Monitor, 2025).

However, South Korea has one of the lowest shares of renewable energy of any country in the OECD and G20. The pace of future deployment also remains uncertain. While former President Yoon Suk-yeol decided to drop South Korea’s renewables target outlined in its 2021 NDC, and reversed his predecessor’s denuclearisation policy (2017–2022), claiming that renewables are “too expensive”, the new government has signalled its intent to expand South Korea’s renewable energy sector, though concrete new policies are yet to emerge.

A study suggests that South Korea’s ample renewable energy resources would be able to generate almost 5000 TWh annually from wind and solar, with offshore wind and open-field PV holding the highest technical potentials (Climate Analytics, 2023). Several underlying issues around renewables development include complex permit and bureaucratic systems, an outdated and inefficient market system and grid limitations, contributing to industries’ and public reluctance towards renewable energy (Buchan, 2023; Climate Analytics, 2023; IEEFA, 2024).

The 11th Basic Plan, finalised in early 2025 under the Yoon administration, outlines electricity generation sourced from renewables at 22% and 33% by 2030 and 2038, respectively (Kim, 2025). This has not improved from the initial share in the 10th Plan, and falls short of the 30% renewables target from its 2021 NDC. This also compares poorly with other OECD countries, already at an average share of 34% renewables in 2023 (IEEFA, 2024).

The Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) replaced the feed-in tariff scheme in 2012 and is the main policy instrument to promote renewable energy. The RPS scheme requires major electricity utilities (capacity over 500 MW) to generate a specific electricity quota from renewable and “new energy”, which comes with fines upon failure to meet the target.

Obligations can be fulfilled through investing in direct renewable generation and purchasing Renewable Energy Certificates (REC). The RPS quota in 2022 was 14% and is planned to increase from 17% to 25% from 2023 to 2026. However, the government amended the plan in 2023 through the Renewable Energy Act. The annual RPS was reduced to 13% and 15% by 2023 and 2025, respectively, and extended the 25% quota target for 2030. Further RPS quota adjustment is expected in 2025. A study has reported that many utilities companies have failed to meet the target since 2019 (IEEFA, 2024).

The Korean Emission Trading Scheme (K-ETS) has served as the core regulatory framework for renewables since 2015. It regulates the emissions allocation for 804 entities within the power, industrial, buildings, waste, transport, aviation and domestic maritime transportation sectors. The revenue will be allocated to climate mitigation and low-carbon innovation actions (ICAP, 2022).

South Korea still faces significant roadblocks in renewable energy development due to critical gaps and policy shortcomings, including:

- The national energy policy lacks specific renewable energy implementation plans and emphasises alternatives like LNG and ammonia/hydrogen co-firing, which perpetuate fossil fuel use instead of fully transitioning to renewable energy sources. Additionally, a nuclear-centred energy policy dominates, in part overshadowing renewable energy development.

- Past governments have suspended new permits for renewable energy projects in regions like Honam, citing grid saturation, while failing to provide alternative measures or to consult stakeholders. Additionally, restrictive policies on renewable energy generation at controlled substations further stifle development in regions that account for the majority of renewable energy production.

- Lastly, drastic budget cuts and the reduction or abolition of support systems for renewable energy businesses have severely weakened the sector, directly impacting domestic solar power companies and leading to reduced supply and operational struggles (Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 2024).

Recent studies suggest that South Korea would require an additional 1500 TWh of renewable generation by 2035 to fulfil growing electricity demand and phase out fossil fuels. The country has ample renewable energy potential of about 5000 TWh, way above projected demand (Climate Analytics, 2023).

Nuclear

Former president Yoon Suk-Yeol revitalised South Korea’s nuclear power programme and scrapped his predecessor’s nuclear phase out policy (2017–2022). His government pledged to develop a nuclear power roadmap to 2050 to support carbon neutrality objectives and enact necessary legislative support for the nuclear power industry (KBS, 2024).

The 11th Basic Plan for 2024–2038 has specified for “carbon-free” energy (incl. nuclear) to make up 70% of the power mix by 2038, with nuclear power providing over half of that share. The draft plan had proposed the additional construction of three nuclear power plants (4.4 GW) from 2037 to 2038 and one unit of SMR (0.7 GW) by 2036. However, in the final version of the plan, renewable generation targets were slightly increased and one of the proposed new nuclear units was omitted (Kim, 2025).

In 2024, the Yoon government approved two large-scale nuclear projects (namely Shin Hanul units 3 and 4, with a capacity of 1.4 GW per unit), which were on hold since 2017 following the Moon administration’s denuclearisation policy (Agence France-Presse, 2024). The plants are estimated to be completed in 2032 and 2033, respectively (World Nuclear News, 2024). South Korea has 26 reactors operating and two retired reactors, with an additional 3 units in operation expected by 2038 based on the 11th Plan.

The government amended the K-Taxonomy Guideline in September 2022. The adjustments were influenced by the EU’s taxonomy that categorised nuclear energy as a sustainable energy source and eligible for low-interest green finance. The guidelines consist of two classifications of green economic activities, a ‘green’ and ’transition’ category (Jang-jin, 2022). Thus, nuclear projects can now access low-interest financing, signalling strong support to this industry.

Although nuclear electricity generation does not emit CO2, the CAT doesn’t see nuclear as the solution to the climate crisis due to its risks such as nuclear accidents and proliferation, high and increasing costs compared to alternatives such as renewables, long construction times, incompatibility with the flexible supply of electricity from wind and solar and its vulnerability to heat waves.

Industry

In 2023, the industrial sector accounted for 38% of national emissions and around half of South Korea’s electricity consumption (IEA, 2025; Republic of Korea, 2025b). The sector has played a crucial role in South Korea’s economic growth, employing roughly one-fourth of its labour force and contributing to almost a third of South Korea’s GDP (Investopedia, 2024). South Korea’s major manufacturing industries include machinery (vehicles, shipbuilding and general-purpose machinery manufacturing), materials (steel, oil and chemical industries), and ICT (electronics industry, semiconductor) (National Atlas of Korea, 2021).

The main policy regulating industrial emissions is the K-ETS (Korea’s Emissions Trading Scheme), which in Phase 3 (2021-2025) covered 73.5% of national GHG emissions and 685 companies in 69 subsectors, including main industries like steel, cement, and petrochemicals (Republic of Korea, 2021c). Companies subject to the ETS are eligible for financial support from the government, which can be used to install energy-efficient equipment and processes.

In November 2025, the government announced updates to the K-ETS for Phase 4 (2026–2030), including reductions in free carbon allowances and the inclusion of additional sectors. While the reforms tighten the overall emissions cap and are intended to encourage companies to accelerate decarbonization, free allocations will still be maintained for many high-emitting industrial sectors to address competitiveness concerns, which could limit the overall impact of the policy (ICAP, 2025).

As one of the world's manufacturing powerhouses, South Korea’s decision to reduce its emission reduction target in the industrial sector (to 11.4% below 2018 levels by 2030, previously set at 14.5%), has raised concern. The gap will be compensated through renewables energy use and overseas reduction (Ministry of Climate, Energy and Environment, 2023b), with the government arguing it will be able to achieve its 40% cumulative target nevertheless. However, the weakened target shows the government’s intention to delay heavy industry decarbonisation, which needs urgent and progressive action.

The implementation of the European Cross-Border Carbon Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is predicted to considerably impact Korean industry as the EU is a major market for South Korean industrial outputs, accounting for 96% of total EU-Korea trade in 2023 (The EU Commission, 2024). The Korean steel industries are reported to having opposed the EU CBAM together with Japan (Influence Map, 2024). The government raised concerns regarding compliance hurdles, such as reporting systems, complex supply chain requirements, and high compliance costs. The government hopes to negotiate a recognition of the K-ETS scheme and exempt companies that have certified their emissions from the EU CBAM (Kallanish Commodities, 2024).

South Korea has launched several initiatives to promote industrial energy efficiency such as the Korea Energy Efficiency Partnership (KEEP30). The KEEP30 targets the 30 largest energy-intensive companies (accounts for ca. 60% of industrial energy use). The KEEP30 is comprehensive; it covers regulation on energy efficiency standards and labelling, energy audits applied to energy-intensive business, and ETS.

The government also provides incentives such as financial support, tax reductions, consulting, etc. Through its Energy Efficiency Resource Standards (EERS), the government mandated the state-owned energy suppliers (KEPCO and KOGAS) to support large corporations to improve energy efficiency. The energy efficiency policies are regularly revised and tracked, though a more thorough examination of the outcome would be required to quantify their influence (The World Bank, 2023).

The Korean government includes Carbon Capture and Storage (CCUS) as a core mitigation measure in its LTS and plans to capture and store 11 MtCO2 by 2030 (Republic of Korea, 2021a). In February 2024, its National Assembly passed the Act on the Capture, Transportation, Storage, and Utilisation of Carbon Dioxide (the "CCUS Act") as a legal basis to establishment of CCUS business covering administration procedures and licencing, which previously were a major challenge for CCUS related business (MOTIE, 2024b). The CCUS Act also set safety and environmental standard, as well as promoting support schemes such as subsidies, corporate research and development and various technical support (Kim & Chang, 2024).

Heavily relying on unproven CCS for power generation simply prolongs the use of fossil fuels, diverting attention and resources away from the necessary and urgent switch to renewable energy generation that drives down actual emissions.

The use of CCS should be limited to industrial applications where there are fewer options to reduce process emissions—not to reduce emissions from the electricity sector where renewables are cost-effective mitigation alternatives, not least because CCS doesn't remove 100% of emissions from power plants.”

Transport

In 2023, the transport sector contributed 19% (106 MtCO2) of the country's CO2 emissions from fuel combustion (IEA, 2025; Ministry of Climate, Energy and Environment, 2023c). South Korea’s 2021 NDC update set an emissions reduction target in the transport sector of 38% below 2018 levels (about 61 MtCO2e) by 2030.

The South Korean government is supporting electric vehicle (EV) industries through tax incentives, subsidies, expanding charging station instalment and support in production facilities and R&D. In 2024, the government revised its Special Taxation Act, which is a tax incentive for eco-friendly vehicles to be enforced from January 2025, and extended the tax reduction benefit for an additional two years (National Assembly, 2025).

The Korean government provides various subsidies for EVs, depending on the size of the vehicle and its overall performance. The subsidy plan is annually revised to take into account latest policy and demands. In 2024, the government introduced a new EV subsidy plan that contains but is not limited to:

- a change in performance subsidies for all type of EVs,

- subsidies for battery safety for units equipped with On Board Diagnostics-II system,

- incentives for units with fast charging features,

- revised eligibility criteria where subsidies are only applied to vehicle with basic unit price below 85 million KRW (USD 64,008),

- a 20% subsidy for low-income buyers, and a 10% subsidy for young age buyers,

- charging infrastructure subsidies, and more (Jung-joo, 2024).

In 2025, the government further reformed the subsidy scheme, increasing the subsidy for young buyers by 20%, tightening performance and safety requirements for eligible vehicles, and expanding differentiated support for first-time buyers and multi-child households (Ministry of Climate, Energy and Environment, 2025).

In 2023, EVs made up roughly 9.3% of all new car purchases in South Korea, with 162,000 EVs sold from the 1.74 million in total sales (The Korea Times, 2024). This figure represents a slight decline from the 9.7% recorded in 2022, likely due to increasing concerns about insufficient charging infrastructure, higher costs, and safety. On the other hand, the used EV car market is showing an upward trend, accounting for total 2% of total used car sales in 2024 (The Chosun Daily, 2024).

There has been a growing consumer reluctance over EVs, especially due to a recent massive battery fire case in Incheon, leading to panic sales of used EVs. Experts predict this incident will further slow down EV demand in the coming years. Following the incident, automakers are offering massive promotions to counter the EV markets potential decline, while the government plans to prohibit fully charging the battery to deter fires and to initiate a battery certification scheme (Park, 2024).

Following the win of Donald Trump in the 2024 US election, EV-related stocks from major South Korean companies plummeted due to the president-elect's plans to repeal the Biden administration’s EV tax credit. The tax reform would end the USD 7,500 consumer tax credit, putting South Korean EV and battery manufacturers in jeopardy (Ha-Nee, 2024; Lassa, 2024). The Trump Administration went on to enact the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, confirming these concerns, with the industry projecting substantial revenue losses and heightened policy risks for manufacturers exposed to the US market (Sang-Hyeon, 2025).

On December 18, 2023, the Korean government held the sixth Hydrogen Economy Committee meeting. During this meeting, key policy measures were announced to accelerate the transition to a clean hydrogen ecosystem and foster the hydrogen industry. Among the initiatives is the expansion of fuel cell electric vehicle (FCEV) distribution, with a production target of 300,000 FCEVs and installing more than 660 hydrogen charging stations by 2030 (Moon, 2023).

After committing to the Net Zero Government Initiative in 2022, South Korea developed the "Plan for a Carbon-neutral Public Sector", which was finalised by the Presidential Commission on 2050 Carbon Neutrality and Green Growth in November 2023. The plan requires public institutions to exclusively purchase or lease eco-friendly vehicles. To further encourage the adoption of zero-emissions vehicles, the government will reinforce the requirement for public institutions to install charging stations. Additionally, by 2030, South Korea aims to have 83% of the public ship fleet be energy efficient and powered by environmentally-friendly energy sources (Ministry of Climate, Energy and Environment, 2023b)

Buildings

In 2022, the buildings sector emitted 45 MtCO2, representing 8% of the country’s total CO2 emissions. Fossil gas makes up the largest energy source in the residential sector, accounting for half of final consumption, with electricity making up 30%. The residential sector accounts for 12% of final energy consumption (IEA, 2025). South Korea’s net zero roadmap sets a mid-term target of reducing emissions in the sector by 37.6%.

The Green New Deal allocates approximately USD 4.5bn for green remodelling initiatives. This effort aims to ensure that both new and renovated buildings are energy-efficient and built using sustainable materials (Ministry of Economy and Finance, 2020). By 2025, the Green New Deal seeks to remodel 225,000 homes, 440 daycare centres, and 1,148 other facilities. Under the Framework Act on Carbon Neutrality and Green Growth, South Korea plans to develop carbon-neutral cities as parts of its efforts to achieve “spatial carbon neutrality” (Ministry of Climate, Energy and Environment, 2022).

Following its commitment to the Net Zero Government Initiative, South Korea introduced the "Plan for a Carbon-neutral Public Sector." Finalised in November 2023 by the Presidential Commission on 2050 Carbon Neutrality and Green Growth, the plan mandates that newly constructed public buildings above a certain size must obtain zero-energy building certification. All public buildings will be required to implement an integrated intelligent building energy management system (BEMS) to optimise and control energy consumption (Ministry of Climate, Energy and Environment, 2023a).

Methane

In 2022, South Korea’s methane emissions accounted for 4.9% of its total GHG emissions (excl. LULUCF), mainly from the agriculture (49%), waste (36%) and energy (14%) sectors (Republic of Korea, 2025b).

South Korea joined the Global Methane Pledge at COP26. In 2023, the government presented South Korea’s 2030 Methane Emissions Reduction Roadmap. The roadmap sets a target of reducing methane emissions from 28 MtCO2e in 2018 to 19.7 MtCO2e in 2030, a 30% reduction in line with the pledge (CCAC, 2023).

To reach this target, the plan outlines sectoral reductions of 2.5 MtCO2e from the agriculture sector, 4 MtCO2e from the waste sector, and 1.8 MtCO2e from the energy sector by 2030. However, one study shows that South Korea’s 2030 Methane Emissions Reduction Roadmap risks falling short of its ‘methane budget’ aligned with the 1.5°C temperature limit, when compared to certain IPCC socioeconomic pathways. It finds that South Korea’s methane reduction responsibility should be more than twice its current target, or 18 MtCO2e below 2018 levels. The study also criticised that the roadmap only focuses on the 2030 target and lacks long-term measures to 2050 (SFOC, 2024c).

At COP29, South Korea signed the Declaration on Reducing Methane from Organic Waste. The declaration emphasises some key measures, such as integrating a methane target in the NDC, developing roadmaps and regulations for waste and food systems, mobilizing finance, improving data systems, increasing community participation, and tapping into international cooperation (COP29, 2024).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter