Country summary

Assessment

After failing to adopt a reform of its CO2 Act in December 2018, Switzerland is now missing an essential instrument in achieving its 2030 pledge of a 50% emissions reduction, making it even less likely that it will meet this goal without decisive policy action. We therefore rate Switzerland’s currently implemented policies as “Insufficient”. The renewed discussion concerning the update of the law, scheduled for September 2019, presents itself as an opportunity to improve this rating.

In early 2019 Switzerland agreed to link its emissions trading system to the EU ETS, starting in 2020. The much higher prices of EU ETS allowances may also result in higher costs of carbon in the Swiss emissions trading system.

An increase in the carbon levy in 2018 from CHF 84 (USD 84) to 96 (USD 96) per tonne of CO2 was a step in the right direction. With some of the proceeds spent on modernising the building stock and the rest returned to the citizens on per capita basis, the mechanism increases the acceptance for Swiss climate action. A further increase in the levy would accelerate emissions reductions: Whereas the rejected CO2-Act would allow increasing the carbon levy to CHF 210 (USD 209), the CO2-Act in its current form adopted in 2011 allows for this, with a maximum level of CHF 120 (USD 119) per tonne of CO2.

The transportation sector, responsible for almost a third of Switzerland’s emissions, is one of the areas in which accelerated climate action is needed, especially in light of the fact that today’s emissions are higher than in 1990. Despite this worrying trend, no major policy to reduce emissions was introduced – to the contrary, the penalty for importing cars with emissions higher than those prescribed in 2012 was significantly reduced in 2017. While the Roadmap Electric Mobility 2050, adopted in late 2018, introduces the goal of increasing the share of electric vehicles to 15% by 2022, the document has no legal character and the goal is far from what can be perceived as ambitious.

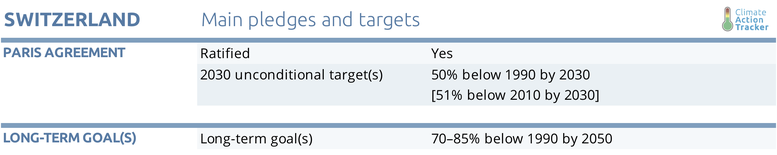

We rate Switzerland’s 2030 pledge as “Insufficient”. The update of the NDC offers an opportunity to increase Switzerland’s level of ambition and improve this rating. For full details see pledges and targets section

A May 2017 referendum adopted the Energy Strategy 2050, a package of measures aiming at increasing energy efficiency, reduction of CO2 emissions, and steadily replacing nuclear energy by renewables, and many of these measures were included in the reform of the Energy Law that went into effect inJanuary 2018.

Transport is particularly important: in 2018 around 3.2% of all vehicles sold in Switzerland were electrically chargeable vehicles. In the first quarter of 2019 their share increased to 5.3%, but with a significant increase in the share of battery-only (4.2%) and a decrease in plug-in hybrid vehicles. While the uptake of electric vehicles accelerates, their share remains significantly below that of some countries with a comparable level of income that makes electric cars more affordable (e.g. 13% in Sweden, 10% in the Netherlands, 61% in Norway).

In December 2018 the Swiss government, responding to consultations with stakeholders from the auto and electricity industries, buildings sector, and local authorities, adopted the new Roadmap Electric Mobility 2050. It includes a goal of increasing the share of electric vehicles in new sold vehicles to 15% by 2022.

Such a goal is unambitious as it barely goes beyond the continuation of the increase already observed. The rate of increase in the share of electric vehicles needed to achieve a 15% share by 2022 is only just above 2% annually, far slower than what’s needed to phase-out the sale of combustion cars altogether by 2035, a goal considered compatible with the Paris Agreement, Also, instead of any actual mechanism to decrease the role of combustion vehicles, the Roadmap instead suggests a public relations approach of “awakening of positive emotions”.

The share of freight transported by rail in Switzerland in 2017 was, at 37%, much higher than in the EU (19%), and appears to be going in the wrong direction. In 2017, the amount of products transported by rail decreased by 7% while the amount of products transported by road increased by 1.5%.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter