Policies & action

NOTE: Our analysis was published before the release of the UK's Carbon Budget Delivery Plan. The CAT will integrate our analysis of the plan into our next assessment.

We rate the UK’s current policies until 2030 as 'Insufficient', when compared to modelled domestic pathways. The UK government needs to step up action to develop and implement climate policies to reduce emissions. Our 1.5°C modelled domestic pathway is based on global least-cost mitigation and defines the minimum level of emissions reductions needed at home to be 1.5°C compatible. It should be taken as the floor, not the ceiling, for domestic ambition.

Although UK climate action is insufficient, it is moving in the right direction – just too slowly. Stalled progress prior to the change in government in 2024 has meant that, without immediate and rapid change, the UK can no longer be considered a leader in global climate action. The new government’s climate action has indeed shifted UK policy closer to aligning with a 2°C trajectory, but this policy shift has not been deep enough to improve its rating as of 2025.

The 'Insufficient' rating indicates that the UK’s climate policies and action in 2030 need substantial improvements to be consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C. If all countries were to follow the UK’s approach, warming would reach over 2°C and up to 3°C.

Further information on how the CAT rates countries (against modelled domestic pathways and fair share) can be found here.

Policy overview

Over a year into the new UK government’s tenure, the direction of UK climate policy is becoming clearer. After inheriting a growing implementation gap where action drifted further away from achieving government targets, a significant shift was needed to get the UK back on track and meet its NDC goals.

When the new government took power in July 2024, only 24–32% of the emissions cuts needed to reach the UK’s climate targets were covered by credible policy (CCC, 2024). That number has since increased to 32–38% (CCC, 2025b). When plans with some risks (i.e. plans which are mostly satisfactory but carry delivery or funding risks) are included, the share of emissions needed to meet the 2030 NDC rises to 61% (CCC, 2025a). That leaves 39% of emissions which either have significant risks attached or are not covered by credible plans. While an improvement, it hardly represents the seismic shift needed to place the UK on a credible path to achieving its 2030 and 2035 NDC targets.

In 2024, the High Court declared that the UK’s current policies are not compatible with achieving its carbon budgets. Due to the general election results and resulting change of government, the deadline to submit a revised plan which is compliant with its climate targets was extended to October 2025 (Johnson, 2025).

Recent years have seen a breakdown in the cross-party consensus on climate that dominated British politics. The CCC’s science-policy expertise has formed the basis of a strategic approach to climate policy which benefitted from cross-party support, allowing a sustained effort to address a long-term challenge. Fossil fuel industry interests have begun to corrode that cross-party consensus. Weak lobbying laws have allowed the fossil fuel industry to influence legislation and normalise industry talking points (Healy, 2024; Stone, 2025). This influence has served to slow down the transition and, through certain sections of the media, promote opposition to climate policy.

Ultimately, initial resistance to climate policy gives way once the co-benefits are felt. Ambitious climate policy will inevitably see these co-benefits come to fruition, particularly when just transition principles are adequately integrated into policy planning. As the transition at Port Talbot steelworks demonstrate (see the industry section below), however, it is critical to support communities as they shift their local economies away from emissions-intensive industries. A failure to do so will leave communities behind.

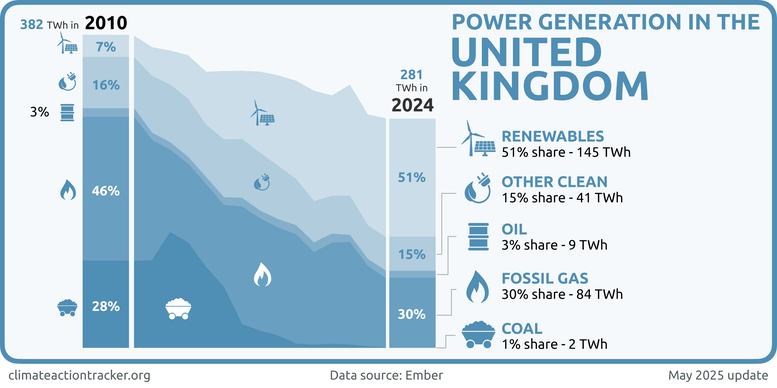

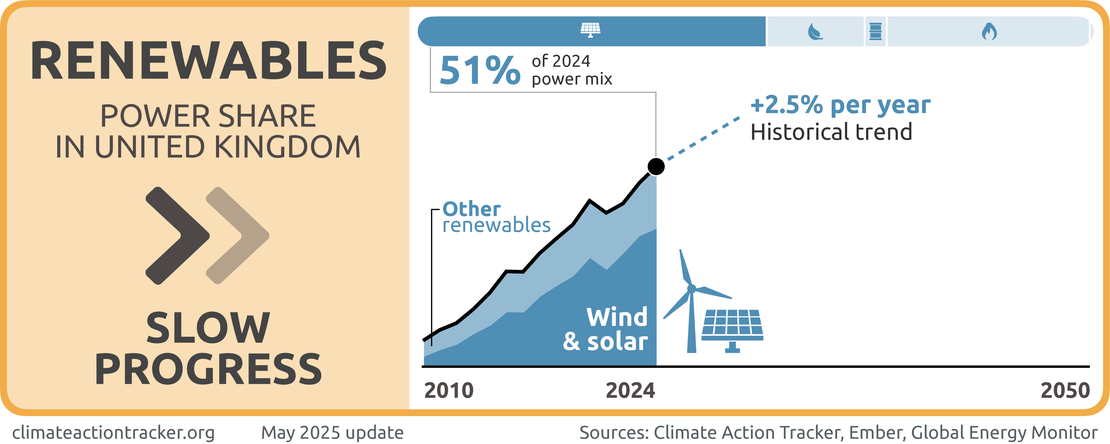

The government’s Clean Power 2030 Action Plan, a cornerstone of its programme, will mostly phase out fossil fuels from the electricity grid while increasing the share of low carbon technologies from 65% in 2024 to over 95% by 2030 (Ember, 2025; UK Government, 2024a). The target is ambitious and should be commended as clear, decisive policy which will bring the UK in line with European leaders like Denmark and Portugal (Ember, 2025).

Similarly, buildings sector decarbonisation is being supported by significant investments – in this case, the government’s Warm Homes Plan, which earmarks GBP 13.2 bn to roll out heat pumps, retrofit hundreds of thousands of homes, and develop homegrown British supply chains for buildings decarbonisation (UK Government, 2024d). This ambition is sorely needed, with the UK’s heat pump rollout currently well behind the European average.

The transport sector is the highest-emitting sector in the UK. The increasing electrification rate, driven by a rollout of electric vehicles and charging infrastructure, is placing government policy broadly in line with the Climate Change Committee’s recommended 2030 pathway, although the rate of progress needs to be sustained (CCC, 2025b).

The UK’s aviation policy, however, risks blowing out its carbon budget to the point of putting the UK’s climate targets at risk. A 180-degree shift in aviation policy is needed unless the UK intends to meet its targets through increased ambition from other sectors. Managing demand from frequent flyers can reduce sectoral emissions without burdening citizens who fly occasionally.

Power sector

The UK aims to build on last year’s successful coal phase-out by increasing the share of low carbon sources in electricity generation to at least 95% (UK Government, 2024a). To achieve this, the UK released the Clean Power 2030 Action Plan, which lays out its strategy to roll out renewables and upgrade the grid to manage higher shares of intermittent power sources.

The plan would lead to a carbon intensity of “well below 50g CO2e/kWh” (UK Government, 2024a). This remains slightly higher than our 1.5°C compatible benchmarks, which would see the UK’s carbon intensity fall to 7–10 CO2e/kWh. Depending on how much the UK relies on fossil gas in 2030, the Clean Power Plan is broadly aligned with our benchmarks.

Nevertheless, meeting the Action Plan’s 2030 target can make a significant contribution to mitigating climate change. The UK’s National Energy System Operator (NESO) considers the plan achievable without increasing costs and, depending on government policy and energy efficiency, can reduce consumer bills (NESO, 2024).

As electricity prices in the UK are well above the European average (Bolton, 2025), cutting the cost of electricity needs to be at the forefront of government policy. In particular, government policy costs (as opposed to wholesale costs or network charges) are 20 times higher for renewables than for gas. By reforming the Renewables Obligation, Energy Company Obligation, Feed-in Tariffs and legacy Contract for Difference payments, the typical household with a gas boiler can see its bills slashed by GBP 190, while households with a heat pump can see savings of GBP 490 (CCC, 2025b). Funding the Renewables Obligation and Feed-in Tariffs schemes can instead come from gas bills, while strengthening the Warm Home Discount can ensure households reliant on gas boilers will also see net savings (Sissons et al., 2025).

The focus must now turn to implementation. Streamlining the planning process, improving grid connections, and procuring enough wind and solar capacity in upcoming auctions will be critical to achieving the UK’s 2030 targets.

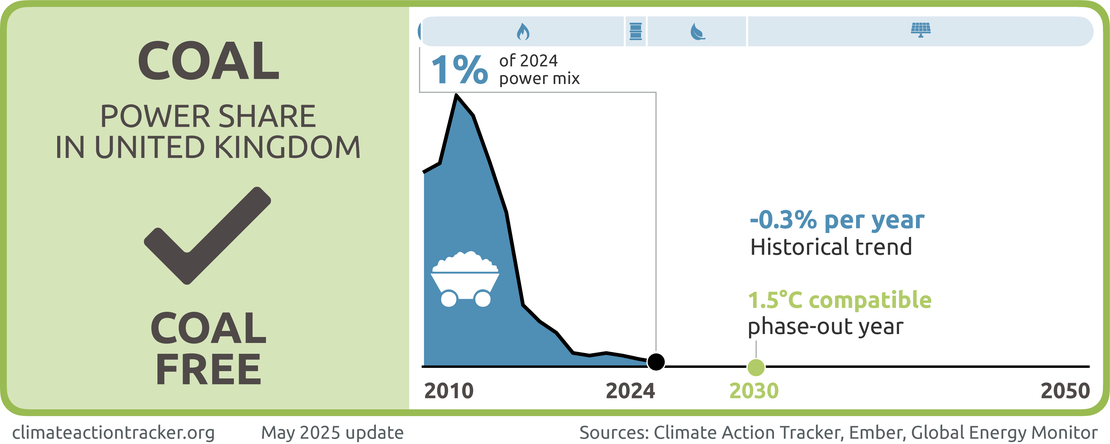

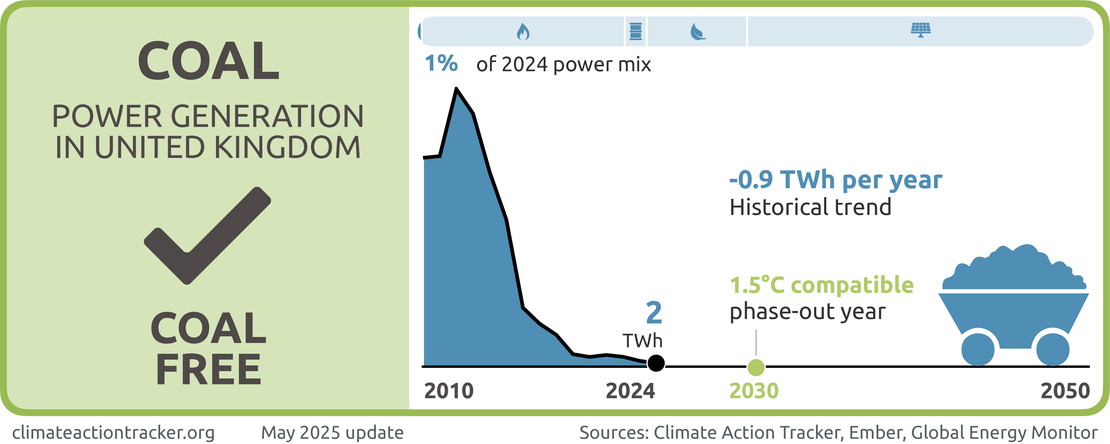

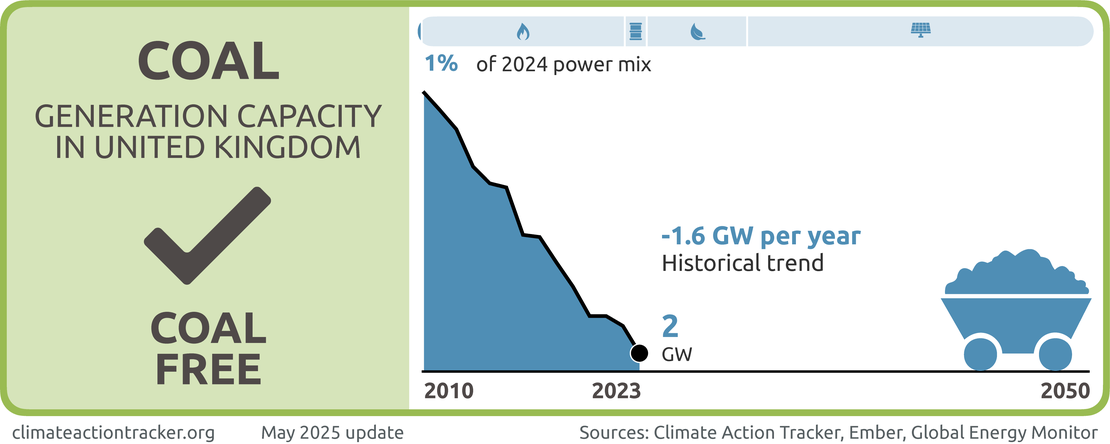

Coal

On the use of coal in the power sector, we evaluate the UK as 'Coal free'.

The UK’s last coal-fired power station closed in October 2024, marking the end of an era. This historic moment puts the UK as a front-runner in the transition away from coal in the power sector, phasing out coal six years ahead of the 2030 deadline for developed countries (Climate Action Tracker, 2023).

The UK’s coal exit is one of its main climate policy success stories of the past decade. As recently as 2012, coal provided 40% of the UK electricity mix (Ember, 2025). The rapid phase-out of coal means that power sector emissions fell, on average, by 10% each year between 2012–2022 (BEIS & DESNZ, 2023).

Fossil gas and oil

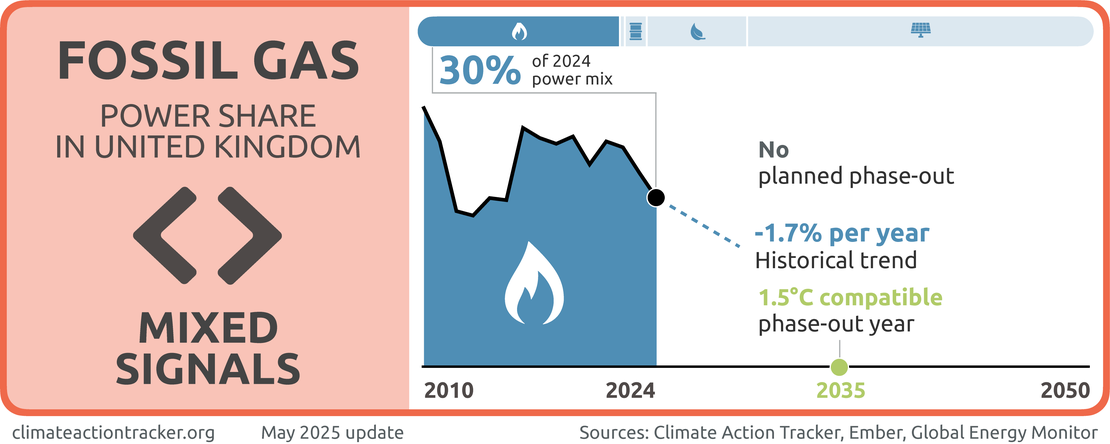

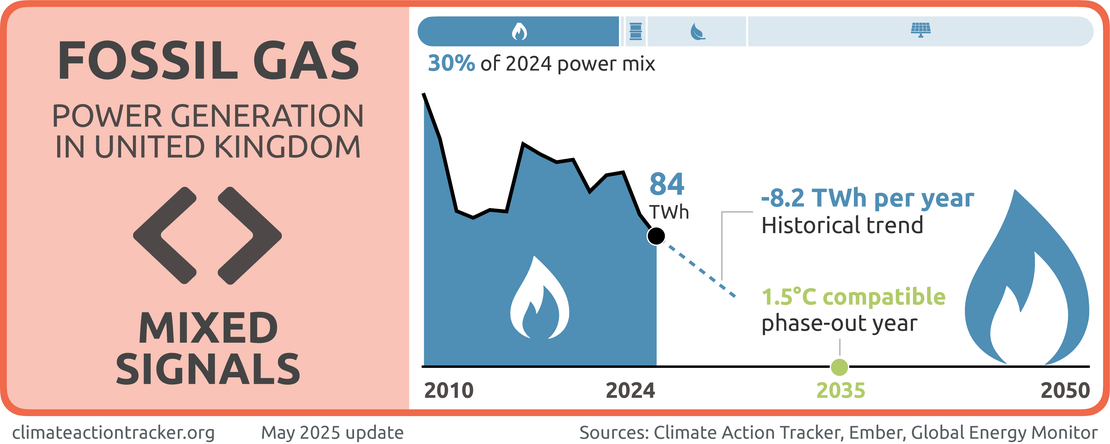

On the use of fossil gas and oil in the power sector, we evaluate the UK as sending 'Mixed signals'. While both the share of energy produced by fossil gas and oil sources and their contributions to the total power supply have fallen over the last five years, gas remains a significant source of the UK’s electricity, providing nearly 30% in 2024. Plans to move away from fossil gas must be accelerated, and the UK must take care not to view fossil gas as an acceptable proxy for truly clean energy.

The UK government’s 2030 “clean power” target maintains some fossil gas in the system, with 5% – at the very most – of generation being met by unabated gas. This represents a significant drop from 2024 levels, when gas accounted for 30% of generation (Ember, 2025). Reducing reliance on fossil gas will be critical to stabilising energy prices, with gas driving a 53% increase in the UK’s wholesale energy prices since 2021 (Evans & Lempriere, 2025). Gas will primarily serve as a dispatchable electricity source to ensure security of supply during periods of insufficient wind or sunshine (UK Government, 2024a).

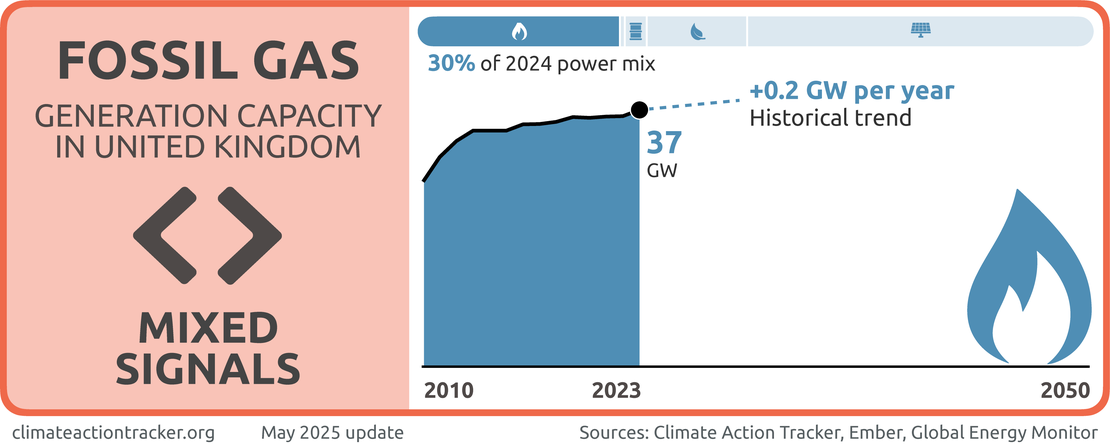

According to the CAT, aligning with the Paris Agreement would see the UK reduce the share of fossil gas to 2–4% of the electricity mix by 2030 and cut this further by 2035 (Climate Action Tracker, 2023). The UK’s target for clean power appears broadly compatible with these benchmarks. In practice, this will mean that size of the gas fleet will remain largely similar to current levels, but it will be used far less (Evans & Lempriere, 2024; UK Government, 2024a).

It is unlikely that the UK will be able to fully phase out fossil gas in the electricity mix by 2030. However, it is possible to substantially cut gas demand. Detailed modelling highlights that the share of gas in the electricity system could fall to below 2% by 2030 without compromising security of supply (Ember, 2022). Once alternative technologies become available at scale to balance renewables’ variability, gas can then be fully phased out.

There is a wide range of options that can help balance a clean grid, including batteries, hydrogen, pumped storage, interconnectors and demand-side management. Modelled scenarios in the Clean Power 2030 plan indicate the UK will bring 2–7 GW of low-carbon dispatchable power online by 2030, which will come from a mix of biomass with and without carbon capture and storage (CCS), gas with CCS, and hydrogen. Additionally, a combination of batteries, long duration energy storage, interconnectors, and consumer-led flexibility is expected to account for 49–59 GW, further reducing reliance on gas to manage renewable variability (UK Government, 2024a).

Fossil gas with CCS should play, at most, a minimal role in the power sector. Detailed modelling suggests that the UK could meet future electricity demand reliably in a grid dominated by wind and solar, with as little as 2.6 GW of fossil gas with CCS in the power sector in 2030, and only 0–5 GW by 2035 (CCC, 2023b; Ember, 2022).

Current CCS projects under development would be sufficient to reach this level. The UK should avoid embarking on a path of heavy reliance on fossil gas with CCS in the power sector, focusing instead on other measures to provide reliable zero-carbon electricity. Deploying turbines which can run on green hydrogen would be a key way to provide long-term flexible electricity generation without relying on CCS.

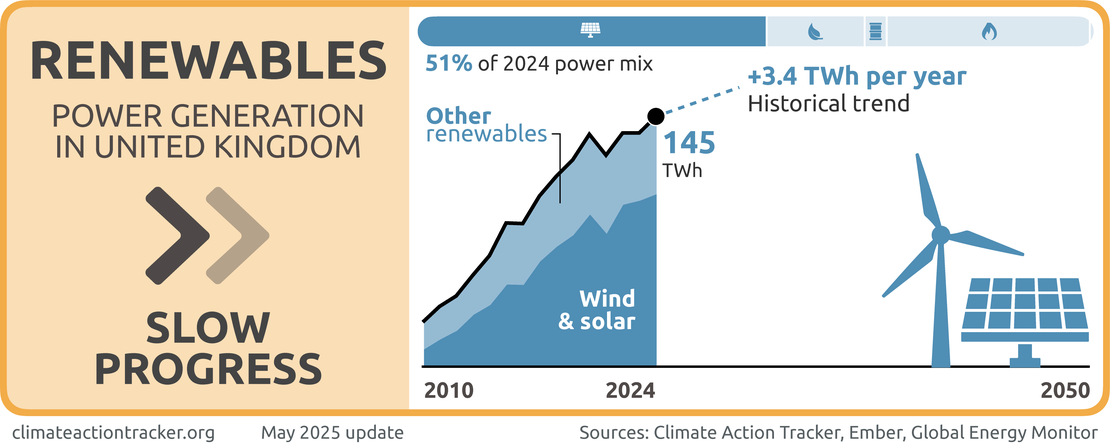

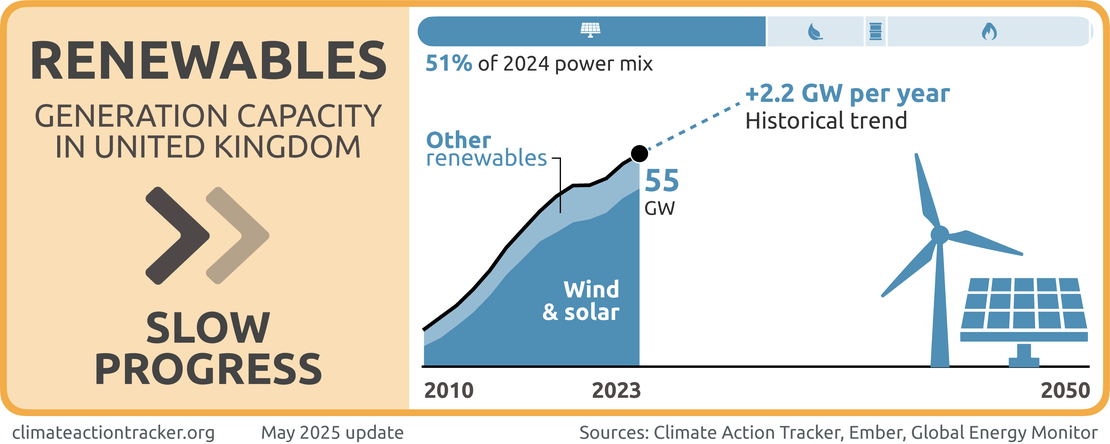

Renewables

On the use of renewables in the power sector, we evaluate the UK as making 'Slow progress'.” For wind and solar sources, both their share of the energy mix and contributions to the total power supply have increased moderately over the last five years. While this is a positive trend, it needs to dramatically accelerate in order to keep the UK on a 1.5°C compatible path to full decarbonisation.

Renewables will form the backbone of the Clean Power 2030 Action Plan. Accelerating their rollout is therefore critical to meeting the 2030 targets. In terms of absolute capacity, the UK government aims to increase installed capacity to:

- 43–50 GW of offshore wind (up from 15 GW in 2024)

- 27–29 GW of onshore wind (up from 14 GW)

- 45–47 GW of solar (up from 17 GW)

Turbocharging renewables will be crucial to aligning with 1.5°C, with the CAT finding that in the UK, the share of renewables in the power sector should reach 84–93% by 2030 (Climate Action Tracker, 2023). The UK’s Clean Power 2030 targets align with this.

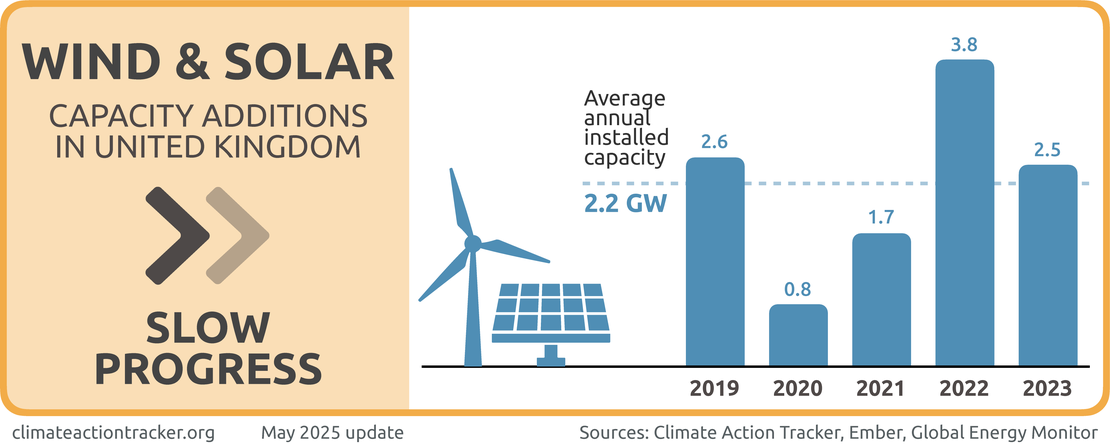

With strong targets in place, the UK’s efforts must now centre around implementation. Getting sufficient renewables capacity connected to the grid and generating before 2030 is a major challenge that requires coordinated planning. The central policy to support renewables deployment is the Contract for Difference (CfD) scheme, which offers a guaranteed price to renewable generators over their lifetime, with the price set by reverse auctions. This has encouraged competition and innovation in the sector and driven large-scale investment and deployment. Both wind and solar capacity has increased significantly, with the last CfD auction securing a record 9.6 GW of new capacity (UK Government, 2024b).

Wind capacity is on track to meet the government’s 2030 targets, helped by the government’s lifting of the de facto onshore wind ban which had been in place since 2015 (UK Government, 2024e). Solar capacity is not yet on track to align with the 45 GW target, however, meaning that the UK will need to ratchet up solar deployment in the near term (CCC, 2025b). The government’s recently-released Solar Roadmap lays out its five-year strategy. This will involve removing barriers to rooftop solar, reviewing regulations on plug-in panels for households, easing up front costs for consumers through lending support, and streamlining the planning process for utility-scale solar projects (UK Government, 2025d).

The UK’s planning system is a barrier not only to solar but to renewables deployment more generally. For years, the planning system wrapped wind and solar projects in red tape, impeding their rollout. The new government has introduced the Planning and Infrastructure Bill which, as of October 2025, is before parliament. As envisioned, the bill aims to streamline the planning process and provide greater certainty to developers and communities alike regarding construction of energy infrastructure (UK Government, 2025c). The government recognises resource constraints as a core reason for planning delays, with over 60% of the Environment Agency’s and 80% of Natural England’s delayed responses stemming from insufficient resources (UK Government, 2024a). This represents a key action item for the government to speed up the planning process.

Just as wind and solar projects are held up by the planning process, so too is the construction of new transmission and distribution (T&D) infrastructure. Any new wind or solar project needs wires and pylons built to connect it to the grid. Without this infrastructure, the projects are left isolated and unable to supply electricity to households and industry. There is currently a significant connections queue, where projects that have already been built are still waiting to connect to the grid (Abbott, 2024).

The rapid renewables rollout means that ever more projects are in need of grid connections. The new government has made substantial progress in this area by moving away from a ‘First Come, First-Served’ queuing system to a ‘First Ready, First Connected’ system (Ofgem, 2025). This new system prioritises projects that show progress in their construction over projects that applied for connection earlier but show no signs of moving towards completion. The new system unclogs the connection queue of ‘zombie projects’ that are years away from being ready. Nevertheless, progress needs to be sustained and further strengthened. Due to the length of time it takes to build T&D infrastructure, most new projects will need to be approved by the end of 2026 if they are to be ready by 2030 (UK Government, 2024a).

Industry

The UK’s Industrial Decarbonisation Strategy introduced by the previous government aims to reduce industrial emissions by two-thirds below 2018 levels in 2035 and 90% by 2050 (UK Government, 2021b). The new government plans to release an updated Industrial Decarbonisation Strategy in 2026. It already released an Industrial Strategy in 2025 which will impact emissions reduction efforts (UK Government, 2025e), though the decarbonisation strategy will provide greater clarity around the government’s agenda for aligning UK industry with net zero.

Industry emissions fell by 9% between 2023–2024, a significant drop. A large part of this reduction came from the steel industry, where blast furnaces at Port Talbot Steelworks are being replaced by electric arc furnaces (CCC, 2025b). These emission reductions need to be sustained, and policies to ensure a just transition for workers need to be rapidly implemented. To align with its climate targets, the UK will need to reduce industrial emissions by around 6% annually (CCC, 2025c, p. 176).

The recently announced linking of the UK and EU’s emissions trading schemes is a step in the right direction for UK industry. The move will accelerate emissions reductions across the UK and EU and is expected to stabilise carbon prices (International Carbon Action Partnership, 2025).

The UK’s current decarbonisation strategy has a three-pronged approach: switching to low carbon fuels, efficiency gains, and carbon capture and storage (CCS).

Fuel switching

In 2024, over 50% of industrial final energy was provided directly by fossil fuels (DESNZ, 2025d). This will need to be reduced substantially on the path to net zero. Two key options are the use of hydrogen, and direct electrification. The Industrial Decarbonisation Strategy set a target of 50 TWh of fossil fuels to be replaced by low-carbon alternatives by 2035 in the manufacturing sector (UK Government, 2021b). Very little progress has been made on this in the last two years, with fossil fuels meeting the same percentage of industrial energy demand as in 2022 (DESNZ, 2025d).

Ensuring widespread access to cheap electricity will be central to reducing fossil fuel consumption. While reducing the national grid’s reliance on fossil gas will stabilise costs, more needs to be done to support the economic case for electrification. As mentioned above, government policy costs are 20 times higher for electricity than for gas (CCC, 2025b). Shifting these costs away from electricity will make it cheaper, allowing industry to decarbonise its energy supply more cost-effectively. The new government aims to cut electricity costs by up to 25% from 2027 for certain energy-intensive industries, for instance through exemptions on the Renewables Obligation and Feed-in Tariffs (UK Government, 2025e).

The government could enhance the business case for decarbonisation by driving demand for low carbon products. Public procurement accounts for around one-third of public sector spending, making it a key lever the government can lean on to drive innovation (Aldersgate Group, 2025). Through green public procurement, public authorities can factor in a product’s environmental impact when assessing bids for a contract. When a product’s carbon intensity is factored into the procurement process, innovative companies are rewarded, thereby stimulating further low carbon innovation.

As noted above, the shutting down of blast furnaces at Port Talbot Steelworks has already had a notable impact on the UK’s industry emissions. The use of electric arc furnaces and recycled steel, which will be up and running by the end of 2027, are expected to cut the factory’s emissions by 90% (Deans & Glyn-Jones, 2025). However, there has not yet been sufficient planning on how to ensure a just transition which preserves jobs in local communities dependent on steelmaking, with 2,800 jobs being lost due to the closure of the blast furnaces. Although the government’s injection of GBP 500 million likely saved the factory from totally closing down, as the ageing infrastructure could not compete with cheaper foreign steel, the loss of half the workforce nonetheless has a huge impact on the local community (Beuret, 2025; Selvaraju & Nick, 2024). There are numerous cases across Europe where the transition to low-carbon steel production has been handled without major job losses, and in some cases several thousand jobs were created (Selvaraju & Nick, 2024). This is a critical gap that must be addressed – one that can only be met through proactive planning from government, industry, and the financial system.

Carbon capture and storage

The previous government set an aim of delivering 6 MtCO2/yr of industrial CCS by 2030, and 9 MtCO2/yr by 2035. This represents around 17% of total abatement in the industrial sector by 2035 (CCC, 2023a). The new government has continued this commitment to CCS, pledging GBP 22 bn of funding to drive CCS projects over the next 25 years (UK Government, 2024c). The government intends to integrate CCS into four industrial clusters (geographical areas with high industrial activity) (UK Government, 2025f). By connecting CCS to these clusters, the government sees a stronger business case for CCS.

However, relying too heavily on CCS to deliver emissions reductions in the industrial sector can be risky, as the majority of previous CCS projects have ended in failure (Abdulla et al., 2020). In many sectors the role and value of CCS is being eroded as the cost of renewables declines (Grant et al., 2021). CCS should be prioritised for applications where there are few alternatives, such as cement production (E3G, 2023).

Fossil fuel supply

Achieving the UK’s climate targets will require strong and sustained reductions in oil and fossil gas production, as well as improvements to the emissions intensity of any remaining extraction. Oil and fossil gas demand will need to fall around 30% by 2030 to achieve the UK’s NDC (CCC, 2020). The CCC also suggested that the emissions associated with oil and fossil gas extraction should fall 68% by 2030, through electrification of processes and addressing fugitive emissions (CCC, 2020).

The previous UK government moved in the opposite direction, continuing to support new oil and fossil gas extraction in the North Sea by approving the Abigail, Jackdaw and Talbot fields (Oil and Gas Authority, 2023; Thomas, 2022; Tidman, 2022). New licensing rounds were held annually (UK Government, 2023b).

The new government has changed course, having committed to end licensing for new oil and fossil gas fields (Lempriere, 2024). This is a good start and should be welcomed. However, it does not address the substantial pipeline of projects which have already received exploration licenses and are either waiting for development consent or are already in production (Dunne, 2024).

The government has published new guidance regarding how to consider applications for oil and fossil gas projects in response to a 2024 Supreme Court ruling which found that new projects should account for the full scope of emissions connected to a fossil fuel project (McCool, 2025). Since the guidelines were published, recent developments in international law have increased governments’ legal exposure if state support is directed towards fossil fuels, including granting new fossil fuel licenses (International Court of Justice, 2025). The government’s decision to end new licenses can therefore be considered in step with international law and reduces its legal exposure, avoiding major infrastructure projects being tied up in the courts. If the UK government grants development consent to oil and fossil gas projects which were approved by the previous government, it risks breaching international law and missing its climate targets.

The UK government can strengthen its position on oil and fossil gas by publicly committing to not approve this remaining pipeline of projects, and to set out a clear path to phasing out UK oil and fossil gas production in line with in Paris Agreement goals, including by joining the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance (BOGA).

Transport

The transport sector is the largest source of emissions in the UK, representing 30% of emissions in 2024 (DESNZ, 2025c). Emissions fell for the second year in a row, with transport emissions falling by 2% compared to 2023 (CCC, 2025b; DESNZ, 2025c). This drop is a result of the increasing share of electric vehicles (EVs) on UK roads, whose numbers have doubled in the last two years (CCC, 2025b). Sustaining this progress will be critical to reducing road transport emissions.

In the CAT’s last UK assessment, we highlighted two core areas which could drive emission reductions in transport – one was to reinstate the 2030 ban on petrol and diesel vehicle sales, and the other was to support EV uptake by removing barriers for the installation of EV chargers and electric vans.

Regarding the former, the government has reinstated the 2030 ban (Department for Transport, 2025b). This sets an important market signal to automakers and charging infrastructure investors, helping to drive EV uptake.

As for the latter, the number of charging points rose to over 86,000 in October 2025 (Department for Transport, 2025a). This increase is 3,600 lower than January-October of the previous year. As the rate of installations has been much faster in London, speeding up the rollout of charging points outside of the capital – especially ultra-rapid charging points on motorways – is pressing (Committee of Public Accounts, 2025). Recent rule changes to planning permission rules for public charging points removes red tape and likely accelerate the rollout of charging stations (Martin, 2025).

Electric van sales, which have been slower to break into the market compared to electric passenger cars, are now seeing an uptick in sales in 2025. Electric vans represented 9% of new van sales in the first nine months of 2025. Though an improvement, this is well below the government’s target of 16% of new van sales. Barriers include range, charging speed, and charger availability (Roberts, 2025).

Aviation

The UK’s Jet Zero Strategy, released in 2022, provides the guiding vision for the aviation sector out to 2050 (Department for Transport, 2022). The strategy aims for domestic aviation to reach net zero emissions by 2040, and total aviation emissions to reach net zero by 2050.

However, in this context, net zero does not mean eliminating the negative climate impacts of aviation, but rather allowing for a large-scale growth in emissions that would be compensated for via the UK emissions trading scheme, CORSIA and other offsetting mechanisms outside the aviation sector. The strategy also ignores the non-CO2 impact of aviation, which represents up to two-thirds of the sector’s overall climate impact (Lee et al., 2021).

The UK’s current strategy relies heavily on speculative technological innovation and carbon dioxide removal to enable a ‘net zero’ aviation sector, without addressing the elephant in the room – demand. Failure to address demand means that aviation is projected to be the highest emitting sector in the UK by 2040 (CCC, 2025c).

CCC pathways show no net growth in aviation demand out to 2035 (CCC, 2025c). The government instead envisages a 70% increase in demand by 2050, to be supported by large airport expansions (Tyers et al., 2025). Indeed, the government states that “the sector can achieve Jet Zero without the government needing to intervene directly to limit aviation growth” (Department for Transport, 2022). Increasing demand is pushing aviation emissions beyond the CCC’s net zero aligned emissions projections, putting the UK’s climate targets at risk (CCC, 2025c).

The UK government’s solution to counterbalance rising demand is to increase the share of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF). Current SAF targets aim to meet 10% of overall fuel use by 2030, rising to 22% by 2040 (UK Department for Transport, 2024). The government seeks to provide revenue certainty to the SAF industry, whereby SAF producers a guaranteed a set price in order to reduce investment risks and stimulate production (Hutton, 2025).

The government is currently on track to meet its 2030 SAF target, with the share of SAF rising from 0.7% in 2023 to 2.1% in 2024 (CCC, 2025c). However, there are supply chain risks connected to SAF. Feedstock limitations represent a supply chain risk for SAF, particularly as there is demand for these feedstocks from other sectors also (Rosales Calderon et al., 2024).

As a result, in 2050, the Jet Zero strategy expects that aviation will still be emitting around 19 MtCO2 per year, which will need to be compensated for by CO2 removal. Given the very limited potential for CO2 removal and uncertainties in the climate system, CO2 removal should be reserved to hedge against climate uncertainties and balance out truly hard-to-abate residual emissions (e.g. from agriculture), rather than to facilitate a stark increase in flying in one of the world’s wealthiest countries.

Key actions to manage aviation emissions can include:

- Include international aviation in an expanded UK ETS. Currently, only domestic aviation and flights to the EEA and Switzerland are included in the UK ETS. Expanding ETS coverage can ensure that the costs of aviation decarbonisation lies with the industry.

- Apply a fuel duty rate to jet fuel. Jet fuel is untaxed in the UK, meaning that airlines pay less tax on fuel than a motorist filling up their car. Independent analyses have found that, if fuel duty were applied to jet fuel, the UK could raise up to GBP 5.9 bn in revenue annually and cut 3.7 MtCO2 in emissions (Transport & Environment, 2024).

- Introduce a frequent flyer levy. 3% of the population account for 30% of flights taken by UK residents (Chapman, 2025). It is critical that demand reductions focus on the sector of the population that use well beyond their fair share of aviation’s carbon budget, not infrequent flyers who want to take an occasional holiday. An increased levy for frequent flyers can nudge demand towards more sustainable forms of travel in an equitable manner (Chapman, 2025; Chapman et al., 2021).

For more information on the need to align aviation and shipping emissions with the Paris Agreement, see the sectoral pages oninternational aviation and international shipping.

Buildings

Buildings were responsible for 21% of UK emissions in 2024 (DESNZ, 2025c). Sectoral emissions rose by 3% compared to 2023, likely due to lower gas prices stimulating more energy use (CCC, 2025b). It is now well established that low carbon technology leads to lower bills – over a 25 year period, a typical three bedroom house in the UK will save GBP 46,600 on their energy bills by installing heat pumps, solar panels and battery storage (The MCS Foundation, 2024).

While households that generate their own electricity can unlock the full benefits of low carbon technologies, many households install heat pumps alone. In these cases, high electricity costs remain a barrier to uptake. Reforming the energy system such as through reduced levies can cut electricity costs so that they are more in line with the European average (Galpin, 2025).

For many households, a key barrier to installing low carbon technologies is this issue of upfront costs. Government support to ease the initial investment can support families to reap the rewards of clean energy. To this end, the government has had mixed success. The number of heat pumps installed in 2024 increased by 56% from 2023, bringing annual installations up to 100,000 (BBC News, 2025; CCC, 2025b). This represents a decent improvement, and demonstrates the efficacy of government incentives – 23,000 heat pumps were installed under the Boiler Upgrade Scheme and similar levels were funded by the Energy Company Obligation (CCC, 2025b).

However, the heat pump market share remains well below the European average and is far from the government’s annual installation target of 600,000 by 2028 (European Heat Pump Association, 2025; UK Government, 2023a). The new government has also weakened policy around fossil fuel boilers, scrapping the 2035 ban on gas boilers and allowing new homes to be built with them. Indeed, 71% of new homes contain fossil fuel boilers (CCC, 2025b; Horton, 2025b). As retrofitting a home later is more expensive than building it with a heat pump, clear government policy in this area is sorely needed.

The Warm Homes Plan is the government’s flagship policy for the buildings sector. The plan earmarks GBP 13.2 bn to roll out heat pumps, retrofit hundreds of thousands of homes, and develop homegrown supply chains for heat pumps and other technologies which will decarbonise the buildings sector (UK Government, 2024d).

Heat pumps work better in well insulated buildings with lower energy demand (BRE Group, 2022). Given UK homes are poorly insulated relative to the European average, blending the heat pump rollout with a comprehensive insulation programme can increase uptake and cost savings for consumers (Innovation News Network, 2023). Serious failures exist with the UK’s current market-based approach to home insulation, with tens of thousands of homes being left with faulty installations (Archer-Brown et al., 2025). While the Warm Homes Plan is a step in the right direction in terms of reducing emissions reductions and lifting thousands out of fuel poverty, a transformative approach must be taken to ensure that the workforce is adequately trained and comprehensive oversight exists.

The government still has not implemented a comprehensive programme to decarbonise public sector buildings. While there has been some progress under Phase 4 of the Public Sector Decarbonisation Scheme, investments will need to be ratcheted up if there is to be a noticeable reduction in emissions (CCC, 2025b) Public buildings such as schools, hospitals and administrative buildings not only represent a low-hanging fruit which can deliver substantial emissions reductions quickly, but can support the development of low carbon industry through green procurement which can drive low-carbon domestic industry. Policies to decarbonise commercial buildings are even further behind, with policy in this area weak and ineffective.

Agriculture

Agriculture was responsible for 12% of UK emissions in 2024 (DESNZ, 2025c). There has been very little progress made in agricultural decarbonisation over the past decade.

The government should work with farmers to ensure they are fairly compensated for implementing sustainable farming practices. Removing barriers and providing financial incentives to preserve and restore habitats, diversify crops, and utilise farmland for renewable energy can shift farming practices to more sustainable methods, while providing much needed income to small farmers.

Key actions for the government include:

- Introducing policies to hedge against the risk of delivery failure. The existing approach to agricultural decarbonisation has relied heavily on measures which are technological and voluntary in nature: this is a significant delivery risk. Productivity improvements on their own will not necessarily reduce emissions, with a risk that farmers simply increase herd numbers instead of freeing up land. Policies need to be developed to address these risks.

- Introducing measures to address dietary change and food waste prevention. The government’s updated food strategy highlights the need to support a shift to more balanced diets that are higher in fruit and vegetables. (UK Government, 2025a). There are clear health benefits to doing so, along with evidence of consumer appetite for reduced meat consumption (Stewart et al., 2021; UK Government, 2022).

Meat intake has been falling in recent years, with the average person’s diet containing 100 grams less meat in 2022 than it did in 2020 (CCC, 2025b). There is also a need to tackle food waste. Given that 9.5 million tonnes of food is thrown out in the UK each year, despite over eight million people living in food poverty (WasteManaged, 2025). The government should work on reducing waste – not only from large businesses, but also at the household, farm and supply-chain stages where most of this waste occurs.

The UK has one of the lowest levels of forest cover in Europe, at 13.5% (Forest Research, 2024). The UK planted 20,700 hectares of new woodland in 2024 (CCC, 2025b). While a significant improvement compared to the year before, it remains well off the government’s target of planting 30 ha/yr by 2025.

This trend was driven primarily in Scotland, but funding cuts to woodland creation in Scotland threatens to jeopardise the growth in new woodland area (CCC, 2025b). To ensure the rate of woodland creation continues to grow, there is a need to provide clear long-term funding, and to streamline processes in order to draw in private capital. Meanwhile, ancient forests must be managed holistically than the current, more linear focus on timber harvesting (Woodland Trust, 2025)

Progress in protecting and restoring degraded peatland – a key habitat – is also well off track, though the situation has improved compared to the year before. The Climate Change Committee recommends that over 60,000 ha/yr of peatland is restored from 2025 onwards. In 2023/24 however, only 18,500 ha were restored (CCC, 2025b). The government’s burning ban on deep peat will help to the UK’s peatlands (Horton, 2025a; UK Government, 2025b). More needs to be done though. To align with its targets, the government needs to ramp up peatland restoration immediately.

Methane

Methane accounted for 15% of the UK’s total emissions in 2023 (DESNZ, 2025a), with 79% of these emissions coming from agriculture and waste (DESNZ, 2025b). The UK is a signatory to the Global Methane Pledge, which sets a target of reducing methane emissions by 30% over 2020–2030. However, to date methane emission reductions are not happening fast enough in the UK. On average, methane emissions have fallen by 1 MtCO2e/yr since 2020 (DESNZ, 2025b). This would need to increase to over 2.1 MtCO2e/yr to align with the Global Methane Pledge.

Specific actions for methane-intensive sectors include:

- Agriculture – methane suppressing feed additives, better slurry management, and dietary shifts away from red meat and dairy.

- Waste – Follow Scotland’s lead by imposing a ban on sending organic waste to landfill.

- Oil & gas – speeding up the phase out of fossil fuels is inevitably the strongest methane reduction measure for the sector. In the meantime, reducing gas leaks, venting and flaring can cut sectoral emissions (Hardy & Benton, 2022).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter