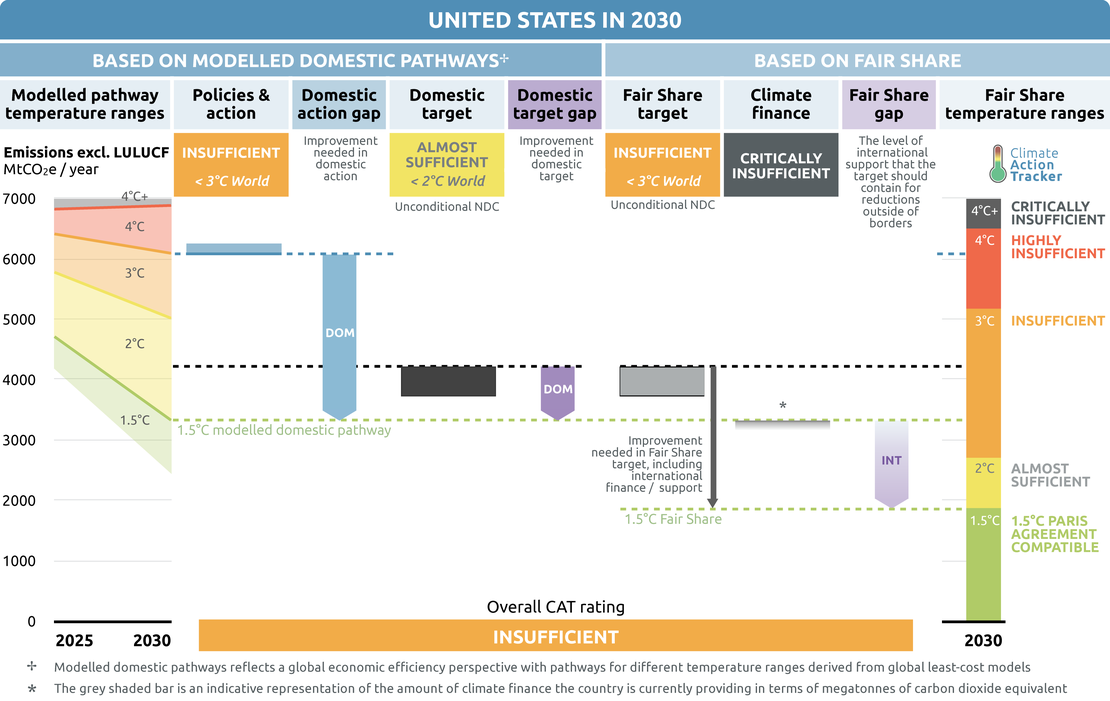

Policies & action

According to our analysis, the US will need to implement additional policies to reach its proposed targets. The projected COVID-19 induced drop in emissions helped the US to meet its 2020 targets under the Copenhagen Accord. The emissions projections for 2020 are 20% below 2005 levels, which is 2 to 6 per cent points lower than the 2020 target (excl. LULUCF).

The Biden administration has set the goal to decarbonise the power sector by 2035, which is consistent with a Paris Agreement pathway. To achieve this, the Biden administration intends to set a Clean Energy Standard (CES) and invest USD 65 billion in modernising the power grid as part of its infrastructure plan. These measures must still be approved by the US Congress.

President Biden has also begun to target emissions reductions in the transport sector. The Biden Administration has set the goal to make half of all new vehicles sold in 2030 zero-emissions vehicles, which is not consistent with a Paris Agreement pathway. To achieve this, the administration proposed a stricter fuel efficiency and emissions standards for light-duty vehicles. California is again allowed to set more ambitious emissions standards than the federal government that can be adopted by other states, a position outlawed by the Trump Administration. Thirteen other US States and the District of Columbia have signed on to the California standard.

We rate the US policies and action as “Insufficient”. The “Insufficient” rating indicates that the US’ climate policies and action in 2030 need substantial improvements to be consistent with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C temperature limit. If all countries were to follow the US approach, warming would reach over 2°C and up to 3°C. The range of policy projections for the US spans two rating categories: “Highly insufficient” and “Insufficient”.

For such cases, the CAT evaluates which end of the range is more likely. Given the ongoing policy developments and the reversal of the rollbacks of the Trump administration, the CAT finds it more likely that the emissions will follow the lower end of the range. If we rated the upper end of the range, policies and action would categorise as “Highly insufficient”, and this would also shift the overall rating to “Highly insufficient”.

The Biden administration proposed stricter fuel economy and GHG emissions standards for passenger vehicles for model years 2023-2026 and a phase down in the production and consumption of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) over the next 15 years. The implementation of these policies would lead to 2% reduction in emissions in 2030 compared to current policy projections. The quantification of these two policies is reflected in the ‘Planned Policies’ scenario.

Further information on how the CAT rates countries (against Modelled domestic pathways and Fair share) can be found here.

Policy overview

With an anticipated strong economic recovery and without rapid implementation of further policy measures, emissions are expected to bounce back after the worst phase of the COVID‑19 pandemic in the US in 2020. The CAT estimates that US GHG emissions in 2020 will be 9% lower than 2019 and will rise again by 5% in 2021. Other studies estimate a 10% drop in emissions in 2020 (Rhodium Group, 2021b).

The impact of COVID-19 and corresponding lockdown measures in 2020 reduced energy demand in every energy end-use sector and had a corresponding impact on emissions. Energy-related CO2 emissions decreased by 11% in 2020. Transport and electricity generation, the two largest US GHG emitting sectors, saw reductions in CO2 emissions of 15% and 10% in 2020 compared to the previous year, respectively (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2021d).

According to our analysis, the US will need to implement additional policies to reach its proposed targets. If no further policies are implemented, the CAT projects that, after an increase in GHG emissions in 2021-2022, US emissions will remain relatively high and reach between 6.1 and 6.2 GtCO2e/year by 2030 (16%–18% below 2005 levels; and 3%–6% below 1990), excl. LULUCF. The CAT projects US emissions levels in 2030 would be between 64%–68% above the upper limit of the 2030 target if no further climate action or policies are implemented.

Our projections of US policies and action do not include policies in the two pieces of legislation currently before Congress: President Biden’s USD 1tnAmerican Jobs Plan (infrastructure bill) and the USD 3.5tn budget bill, as the two bills have yet to be passed by the House of Representatives and are subject to negotiation.

The US is very likely to achieve its 2020 targets, as the projected drop in emissions due to the COVID-19 pandemic would result in emissions of about 20% below 2005 levels in 2020 (excl. LULUCF) and its 2020 target is 14%–18% below 2005 levels (excl. LULUCF).

Compared to CAT projections in July 2020, US emissions projections, based on existing policies, have increased by 1%–7% in 2030. The main drivers of this increase are:

- Policy rollbacks passed by the previous administration;

- Emissions in 2030 are higher due to an update of the estimation of 2020 emissions, which are slightly (2%) higher than initially anticipated, and are followed by a spike in emissions in 2021 and 2022 because of COVID‑19 recovery, and remain at high levels until 2030.

The impact of policy rollbacks and updated estimations of 2020 emissions are partly offset by lower emissions in the electricity sector. The EIA’s Annual Energy Outlook 2021, used as the reference scenario for the current policy projections, projects 5% lower emissions from electricity generation in 2030 compared to the 2020 outlook, with increased electricity generation from renewables, and decreased generation from coal. Coal is now projected to account for 15% of generation in 2030 (down from the 17% projected in 2020), renewables for 35% of electricity generation (up from to 32% projected in 2020), and gas remains at a 35% share, with nuclear making up the rest (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2021a).

Increased state and local action, in addition to market pressures, may contribute to additional reductions. A pre-COVID-19 analysis of recorded and quantified commitments from sub-national and non-state actors in the US suggests that if these commitments were fully implemented they could lead to substantial reductions (America’s Pledge, 2019). If subnational efforts are reinforced with strong federal climate policies over the next decade, the US could reduce emissions 49% below 2005 levels by 2030. These commitments are not included in the CAT current policy scenario unless they are supported by implemented policies (see table below).

In December 2020, over 1,800 US private and financial institutions signed a statement calling for a national climate target that is “ambitious and equitable”. In 2021, prior to the announcement of the new NDC, the group “America Is All In” was launched with a call to at least halve US emissions by 2030 and businesses, universities, scientists, activists, and others declared their support for an ambitious NDC (America Is All In, 2021). Similarly, the coalition “We Mean Business,” composed of 408 businesses and investors, signed an open letter to President Biden indicating their support for the Biden administration’s commitment to ambitious climate action (We Mean Business coalition, 2021)

The interest, engagement and commitment of non-federal actors in climate action enhances the feasibility and credibility of achieving ambitious climate targets, which require the buy-in and commitment of the private sector, civil society and subnational institutions. The importance of this alignment is evidenced by the impact of climate actions coming from non-federal actors, who counter-balanced the inaction of the federal government in climate policy over the past four years.

Selected state level policies included in CAT projections

The CAT current policy projections for energy-related CO2 emissions are based on the EIA’s Annual Energy Outlook (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2020), which includes the following state level policies:

- California Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006 (SB32)

- California’s cap and trade system (California Global Warming Solutions Act)

- Repeal of California Advanced Clean Cars program including the Zero Emissions Vehicle program.

- 30 State Renewable Portfolio Standards and the District of Columbia Renewable Portfolio Standards

- Northeast Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative

- State motor fuels taxes

Recent developments

On his first day in office, on January 20 2021, President Biden signed an Executive Order to re-join the US to the Paris Agreement, reversing the active undermining of climate ambition of the previous four years, and signalling that the incoming administration puts climate at the centre of its agenda. President Biden also signed other executive orders that directs agencies and departments to enact climate-friendly policies across the government and to review and address the promulgation of the climate rollbacks of the previous four years (The White House, 2021j, 2021b, 2021k).

The high priority that the Biden administration places on climate change is explicitly stated in one of his first executive orders “Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad”. The executive order reaffirms the goal to achieve net zero GHG emissions by 2050, encourages a government-wide approach to tackle climate change, mandates the use of federal purchasing power, property and public lands and waters to support climate action, and establishes high-level interagency groups to facilitate coordination, planning and implementation of climate action at federal level (The White House, 2021b).

The executive order establishes the creation of the Climate Policy Office, the National Climate Task Force, the White House environmental justice advisory council (WHEJAC), and the Interagency Working Group on Coal.

- The Climate Policy Office is responsible for the coordination of climate policy-making processes and ensure that domestic climate-policy decisions and programs are consistent with climate targets.

- The National Climate Task Force consists of cabinet-level leaders from all federal agencies and senior White House officials to mobilise and facilitate the organisation and deployment of a government-wide approach to tackle climate change, and facilitate planning and implementation of key Federal climate actions.

- The WHEJAC aims to increase the Federal Government’s efforts to address environmental injustice through monitoring, enforcement and advisory in climate mitigation, adaptation, clean energy transition, among other areas.

- the Interagency Working Group on Coal coordinates the identification and delivery of Federal resources to revitalise the economies of coal, oil and gas, and power plant communities as the country shifts to a clean energy economy.

The Biden administration also directed heads of agencies to identify fossil fuel subsidies and take steps to stop them, suspended oil and natural gas drilling leases in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and revoked the permits for the Keystone XL pipeline (The White House, 2021b, 2021a; U.S. Department of the Interior, 2021b). Less encouragingly, the Biden administration has defended a new oil and gas project in the North Slope of Alaska (The New York Times, 2021a)

In addition to the immediate actions taken via Executive Orders, the Biden administration has taken important steps to break with his predecessor and pursue a green recovery. The American Rescue Plan Act, signed into law on March 11 2021, primarily focused on COVID-19 and economic stimulus measures for households, but also included a number of climate-relevant provisions. The law provides over USD 30bn to assist mass transit systems that experienced funding shortfalls from reduced ridership during the pandemic. The law also provides USD 350bn to state and local governments which play an important role in implementing and enforcing local energy and climate measures (U.S. Congress, 2021).

In late July, the US Senate passed a USD 1tn infrastructure investment bill (“Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act”) with bipartisan support, which aims to spur economic recovery and update the country’s infrastructure while accelerating climate action. The bill includes USD 550 billion in new spending, while the rest is comprised of previously-approved funding. Overall, the plan focuses spending on transit, pollution clean-up and to upgrading the nation’s infrastructure to be better prepared against the impacts of climate change such as intensifying wildfires, hurricanes and flooding (U.S. Senate, 2021b).

Although it would be the largest federal investment into infrastructure projects in more than a decade, the roughly half trillion USD in new spending is less than a quarter of the size of the more ambitious infrastructure investment plan that President Biden originally proposed in March (the USD 2.3tn “American Jobs Plan”). Compared to the original plan, the bipartisan bill significantly scaled back or eliminated most of the components relevant to climate action, including investments in clean energy, transport infrastructure, industry, buildings, and research and technology infrastructure. The implementation of a more ambitious plan such as that originally proposed would be key to helping the US transition and reach its climate target of reducing greenhouse gases 50%-52% below 2005 levels by 2030 (The White House, 2021i).

The following components were removed from the final version of the bill passed by the Senate:

- USD 35bn investment in R&D in climate science, clean technology, and innovation (such as research and demonstration projects in utility-scale storage, CCS, hydrogen, floating offshore wind, etc.).

- USD 46bn investment in clean energy manufacturing.

- USD 40bn investment in sector-based training programs focused on growing clean energy and manufacturing sectors.

- Extend the 48C tax credit, which originally provided a 30% investment tax credit to 183 domestic clean energy manufacturing facilities.

- Eliminate tax preferences for fossil fuels and make sure polluting industries pay for their emissions.

Other sectoral elements of the “Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act” and their differences with the original proposal are presented in the analysis of each individual sector.

Before President Biden can sign it into law, the infrastructure bill must still pass the House of Representatives. The legislation might face delays in the House of Representatives until the Senate passes a far more ambitious USD 3.5tn budgetary plan bill. This budget proposal, presented by the Democrats and intended to pass later this year through a budget reconciliation, is expected to contain many of the climate-ambitious components that were left out of the bipartisan infrastructure plan, such as billions on direct payments to utilities achieving clean energy goals or to incentives to make homes more energy efficient. However, it is expected to face significant obstacles and it will likely not receive the bipartisan support of the infrastructure plan.

Non-state actors have also urged the need for green stimulus packages for the US. An open letter (“A Green Stimulus to Rebuild Our Economy”) from a group of climate and social policy experts in academia and civil society (Green Stimulus Proposal, 2020) proposed a recovery package to create millions of green jobs and accelerate a Just Transition away from fossil fuels. The Bluegreen Alliance urged the US Congress to pass a robust set of stimulus packages that meet sustainability and climate resilience principles and standards.

The proposal includes the following action points: forward-looking planning and investments to meet environmental standards, investment in strategic low-carbon solutions, renewal and expansion of clean energy and tax credits, and establishment of a new loan fund and grant programme for climate-resilient infrastructure, among others (BlueGreen Alliance, 2020). At the state level, New York passed new legislation that makes renewable energy an integral part of New York state’s post-COVID-19 economic recovery (PV Magazine, 2020).

Reversing Trump-era policy rollbacks

On his first day in office, President Biden signed Executive Orders directing all agencies to review and rescind the rollbacks of the previous four years that were deemed a threat to the government’s ability to confront climate change (The White House, 2021b, 2021k). While most of the rollbacks have been addressed in one way or another, many are still pending on final rulemaking (The New York Times, 2021c; Washington Post, 2021).

In May 2021, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) rescinded a Trump-era regulation that restricted which public health benefits could be factored into new air rules (know as the cost-benefit rule). The original rule effectively weakened the government’s ability to curb air pollution and it would make it easier for polluting companies to fight regulations in court. The new rule changes the way cost-benefit analyses are used, which is now designed to allow the EPA to factor in the economic costs and co-benefits of new clean air and climate change rules by allowing regulators to put a price on proved health benefits (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2021e).

Other sector-specific rollbacks from the previous administration and their status are addressed in each of the sectoral analyses below.

While these are positive developments, it is not enough for President Biden to simply restore environmental rules and reverse the previous administration’s rollbacks on climate policy. The US needs to step up climate action and implement ambitious polices to reduce its own emissions by 2030 that are at least consistent with its own climate target (NDC), if not the Paris Agreement 1.5°C warming limit.

Finance

The Biden administration announced its International Climate Finance Plan the same day the US submitted its new climate target. The plan focuses on the role of the US to scale up and mobilise international climate finance and align it with country needs, strategies, and priorities to help unlock deep GHG emissions reductions in developing countries. Notably, the plan also calls for a phase out of international finance for “carbon intensive fossil fuel-based energy” both bilaterally and through multinational fora (The White House, 2021e).

The plan aims to provide the US government with a strategic vision on international climate finance with a 2025 horizon and outlines instruments to mobilise USD 100bn a year for developing countries from public and private sources. With this, the US intends to double annual public climate finance to developing countries by 2024 (relative to the average level during President Obama’s second term, 2013-2016). The plan directs US departments, agencies, and development partners to define a climate change strategy and incorporate climate considerations into their international work and investments. The US also intends to ensure that future reporting is transparent and aligned with the strategic approach to climate finance (detailed reporting, tracking finance and enhanced reporting on mobilisation and impact).

Domestically, the US Treasury has taken a lead role in redirecting financial flows to support climate action with a new “Treasury Climate Hub” and “Climate Counsellor” to coordinate the different climate activities in domestic finance, economic policy, international affairs, and tax policy.

An additional Executive Order from the White House has called for “consistent, clear, intelligible, comparable, and accurate disclosure of climate-related financial risk” (The White House, 2021c). The US Securities and Exchange Commission had already started a public consultation on disclosure so as to enable investors to make better informed decisions considering climate risks (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, 2021). In line with the new policy, the US EPA has already urged the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (an independent body), to consider lock-in and stranded assets risks for gas pipelines (S&P Global Market Intelligence, 2021).

Electricity generation

Electricity supply contributed to 25% of the total 2019 US GHG emissions (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2021a). Total annual emissions in the power sector have declined steadily since 2010. The decline is mainly driven by a shift in generation away from coal to lower and non-emitting sources of generation, such as natural gas and renewables (see below).

In line with positions announced during the election campaign, the Biden administration has announced a target of a carbon-free electricity system no later than 2035. This target has been reiterated in several official documents, including the submission of the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), all executive orders relevant to climate change signed and other national plans, including Biden’s proposed infrastructure plan (“American Jobs Plan”).

In one of his first Executive Orders, President Biden ordered federal agencies to develop a procurement plan for carbon-free electricity in line with this target, an initial step towards meeting this objective (J. Biden, 2020; The White House, 2021b; US Government, 2021). In addition to the Executive Orders however, this target will require other policy changes including laws that must be passed by the US Congress.

This goal is aligned with the Paris Agreement, based on the benchmarks defined by the CAT: our analysis indicates that, to be compatible with the Paris Agreement 1.5 ̊C temperature limit, emissions in the US power sector need to be rapidly reduced to reach zero in the 2030’s (Climate Action Tracker, 2020).

By 2019, total GHG emissions in the US were already 13% below 2005 levels (incl. LULUCF). This trend was primarily driven by emission reductions in the US power sector, which decreased by 33% in 2019 compared to 2005 levels (equivalent to 92% of the total emissions reduction since 2005).

Emission reductions in the sector have been mainly driven by market forces that increase the participation of cheaper renewables and gas in the energy mix, replacing dirtier coal. A full decarbonisation of the power sector by 2035, as pledged by President Biden, would alone reduce emissions by 20%-25% below 2005 levels by 2030. If this plan were accompanied by ambitious electrification policies in other sectors, such as defining a 2030 target of 100% national EV sales or electrification of building heating, it would put the US on track to meet the new target under the Paris Agreement of 50%-52% below 2005 levels (incl. LULUCF).

However, additional policies are needed to reach the proposed goal. The emissions intensity of total electricity generation in the US has decreased over the past 15 years, from 636 gCO2/kWh in 2001 to 433 gCO2/kWh in 2016. If no additional policies are implemented, the CAT projects that emission intensity of electricity generation would be around 254 gCO2/kWh in 2035, a long way from the goal of 0 gCO2/kWh.

Recent developments

The economic crisis resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic and the reduced energy consumption led to a slowdown of carbon dioxide emissions from the power sector in the US in 2020. This is largely explained by the strong link between economic activity and the dominance of fossil fuel sources of energy. After decreasing by 2.8% in 2019, U.S. energy-related carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions decreased by 11% in 2020 compared to the previous year (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2021e).

The lockdown and changes in lifestyles have also had an impact on the supply and demand of electricity, altering the participation of renewables and coal in the sector. As a consequence of the economic slowdown, electricity demand in the US declined by 4% in 2020. However, the reduction in total power generation is not evenly distributed among energy sources (Rhodium Group, 2021b; U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2021e).

In 2020, coal generation fell by 20% compared 2019 levels, while generation from wind and solar grew 26% and 14%, respectively (leading to an increase in the share of renewables in the generation mix to 20% in 2020, compared to 17% in 2019). This is explained because, at every moment, electricity is generated with the cheapest resources available (i.e., economic dispatch). Most of the decline in electricity supply is reflected in lower generation from fossil fuels, especially coal-fired power plants that are more expensive to run than renewable plants that cost little to operate and do not require fuel to generate electricity.

Even before the pandemic, coal-fired power generation had declined year on year over the last decade, while natural gas and renewable sources, mainly wind, increased their share in the generation mix. In 2016, natural gas became the main source of power generation that was previously dominated by coal, and in 2019, onshore wind leapt forward to become the number one source of renewable electricity. These changes are mainly driven by market forces that increase the participation of cheaper renewables and gas.

The reduced participation of coal‑fired generation in the energy mix is not only a result of the pandemic but mainly because market forces and emission requirements (such as for mercury and toxics) over the last decade have displaced coal with cheaper renewables and natural gas energy sources. As a result, the average capacity factor of coal power plants dropped from 72% in 2008 to 47.5% in 2019, electricity emissions intensity has been constantly decreasing (see figure above), and in 2017, the electricity sector, for the first time, dropped from first to second-highest GHG emissions source in the country, with the first place now taken by the transport sector.

Coal plant retirements were already accelerating before the pandemic. In 2019, a total of 13 GW of coal-fired plants retired, the same amount as in 2018 and as twice as much as in 2017. Between 2008 and 2020, coal-fired generating capacity decreased from 313 GW to 223 GW. Over the course of 2021, as of April 2021, six coal-fired power plants have been retired, totalling about 729 MW of capacity, and an additional 3.7 GW of coal-fired capacity is expected to be retired by the end of the year. Cheaper renewables and gas in recent years have put coal-fired power producers under economic pressure, with eight of them filing for bankruptcy in 2019. The Tennessee Valley Authority, a US-owned utility, plans to shut its four remaining coal plants by 2035, totalling 6 GW of capacity combined (Krauss, 2019; Reuters, 2021b; U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2021b, 2021c).

Through Executive Orders, the Biden administration aims to use government purchase power, property and public lands and waters to increase renewable energy on public lands and set a goal to double offshore wind by 2030 (The White House, 2021b).

As a first step, the Biden administration announced a plan to deploy 30 GW of offshore wind by 2030, gave access to USD 3bn in federal loans for offshore wind and transmission projects and completed an environmental review for the first offshore wind project in the country, an 800 MW offshore wind energy project off the coast of Massachusetts, expected to come online by 2023. While these siting permits faced several delays with the previous administration, the Biden administration streamlined the process. Another 12 offshore wind projects are under federal review (The White House, 2021f; U.S. Department of the Interior, 2021c, 2021a)

At the subnational level, 30 states and district of Columbia have enacted mandatory renewable portfolio standards (RPS) and, by the end of 2020, nine had voluntary renewable energy targets. Of these renewable portfolio standards, nine states and the District of Columbia have enacted 100% clean electricity goals into legislation. Virginia was the latest state to establish a renewable portfolio standard (100% carbon-free or renewable energy by 2050), where previously only a voluntary renewable portfolio goal was in place (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2021f). Five US cities have already achieved their goals of 100% renewable energy (America’s Pledge, 2019).

The ongoing record-breaking cost reductions of renewable technologies and state-level RPS, which provide regulatory certainty, have driven the steady increase in the share of renewables in the US electricity generation mix since the turn of the century, reaching a record of 20% in 2020. The CAT projects that this share will continue to increase in the future, reaching 35% in 2030 and 42% 2050. However, these penetration levels are not enough to meet President Biden’s goal of a carbon-free power sector by 2035.

President Biden is urging Congress to pass a nationwide clean electricity standard, which would require power providers to get a certain amount of their energy from fossil-fuel-free sources (Reuters, 2021d; The White House, 2021i). However, the design and level of ambition of the clean electricity standard is unclear, and could also include nuclear and carbon capture and storage (CCS). Further, this measure also faces a long and uncertain road, given it would also need to be passed by the US Congress.

In April 2021, shortly before the US announced its new NDC, 13 major publicly owned electric utilities signed a letter requesting President Biden to require power companies to generate a certain percentage of their electricity from clean sources (i.e., nationwide clean electricity standard). The companies argued that such a mandate was both achievable and necessary to achieve a deep decarbonisation of the power sector. This mandate, which also demands to encourage flexibility in the system, would ensure a reduction of about 80% of the sector’s emissions by 2030 and put the country on track to reach net-zero emissions by 2050 (Reuters, 2021a).

Economic recovery

The USD 1tn Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act passed by the US Senate in August 2021 includes a USD 65 billion investment to modernise the nation’s electricity grid, which would increase flexibility and reliability in the system to facilitate the integration of higher shares of renewables. Although it is the single largest federal investment in power transmission in history of the country, it is only a fraction of the sum requested by President Biden in his infrastructure plan proposed in March (USD 100bn). The legislation also includes more than USD 300m to develop technology to capture and store carbon dioxide emissions from power plants, and USD 6bn to support struggling nuclear reactors (U.S. Senate, 2021b).

The bill significantly scaled back or eliminated most of the original components related to clean energy from the investment plan proposed by President Biden in March 2021 (The White House, 2021i). The following elements that were part of the original proposal were removed or scaled back in the final bipartisan plan:

- Utilities funding fell by USD 466bn, including a USD 363bn cut in clean energy tax credits.

- There is no mention of Energy Efficiency and Clean Electricity Standard (EECES) although it was previously referred as the preferred instrument to incentivise development of clean energy.

- Investment tax credit to build more than 20 GW of high-voltage (HV) transmission lines.

- Extension of investment tax credit and production tax credits for renewable electricity generation and storage.

- Extend the 30% investment tax credit to 183 domestic clean energy manufacturing facilities (known as the 48C tax credit).

- Expand the bipartisan Section 45Q tax credit, which aims to support carbon capture and storage (CCS) and retrofits of existing power plants.

- Investment on clean energy research and demonstration projects (including green hydrogen, carbon capture and storage, utility-scale storage).

Beyond the implementation of the investment plan, current policy projections show that emissions from the electricity sector are still lower than our previous assessment due to the greening of the electricity sector as a result of increasing competitiveness of renewable energy and battery storage.

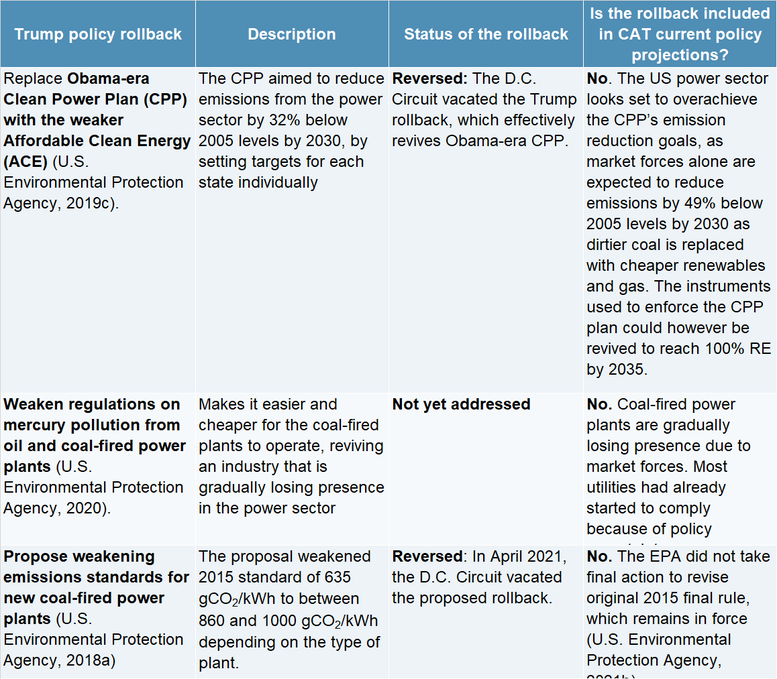

Reversing Trump-era policy rollbacks

On his first day in office, President Biden signed executive orders revoking form President Trump’s Executive Orders deemed to be a threat to the Government’s ability to confront climate change, and directs all agencies to review and rescind the climate rollbacks of the previous four years (The White House, 2021b, 2021k). The following table presents the status of selected rollbacks in the electricity sector.

Oil and gas

In 2018, the US became the world’s largest producer of crude oil (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2018a). While in 2019 crude oil production increased by 11% and exports increased by 48% from the previous year, this trend was interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. The production of crude oil decrease by 8% and crude oil exports grew only by 7% in 2020 compared to 2019 levels (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2021h)

The US is already the largest producer of natural gas (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2018b). In 2019, the US became the world’s third-largest liquified natural gas (LNG) exporter, behind Australia and Qatar (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2019). US LNG exports continued to grow in 2020 despite the economic slowdown derived from the pandemic. LNG exports increased by 31% in 2020 compared with 2019 levels and set an all-time record in March 2021 (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2021g)

Although natural gas is often seen as a ‘cleaner’ source of energy, extracting, transporting and burning it in demand sectors still emits GHGs both through fugitive emissions, as well as through the use of energy in the supply chain. To achieve the Paris Agreement’s long-term temperature goal, the power sector needs to rapidly transition to being carbon-free by around 2030. This requirement for a complete CO2 emissions phase-out results in a dwindling role for natural gas in the power sector (Climate Action Tracker, 2017).

The Biden administration directed heads of agencies to identify fossil fuel subsidies and take steps to stop them, suspended oil and natural gas drilling leases in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and revoked the permits for the Keystone XL pipeline (The White House, 2021b, 2021a; U.S. Department of the Interior, 2021b). Around 25% of US oil and gas production comes from federal land and waters. The suspension of drilling leases reverses one of the last Trump Administration moves that began the process for selling leases to allow oil and gas drilling in the Arctic National Wildfire Refuge (U.S. Department of the Interior, 2019). The temporary moratorium on new permits to extract oil or natural gas on public lands or offshore waters is pending completion of a comprehensive review that includes climate impacts.

The development of the Keystone XL pipeline, which was projected to carry oil from Canada, was blocked by the Obama administration in 2015 but President Trump overturned it within his first days in office. President Biden revoked the permit on his first day in office, and on June 9, 2021, the developer abandoned the project, which was 8% completed. Investments and developments in new oil and gas infrastructure would prevent the US from meeting its 2030 climate target and net-zero emissions goal by 2050, and will lead to significant stranded assets in a Paris Agreement-compatible future.

The USD 1tn Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act includes a USD 21bn investment to plug and clean up abandoned coal mines and oil and gas wells which continue to emit significant amounts of methane and other pollutants long after they are no longer active (U.S. Senate, 2021b). This was one of the few components that increased compared to the original investment plan (USD 16bn). Although the legislation passed the Senate in August 2021, it still needs to be passed in the House of Representatives before President Biden can sign it into law.

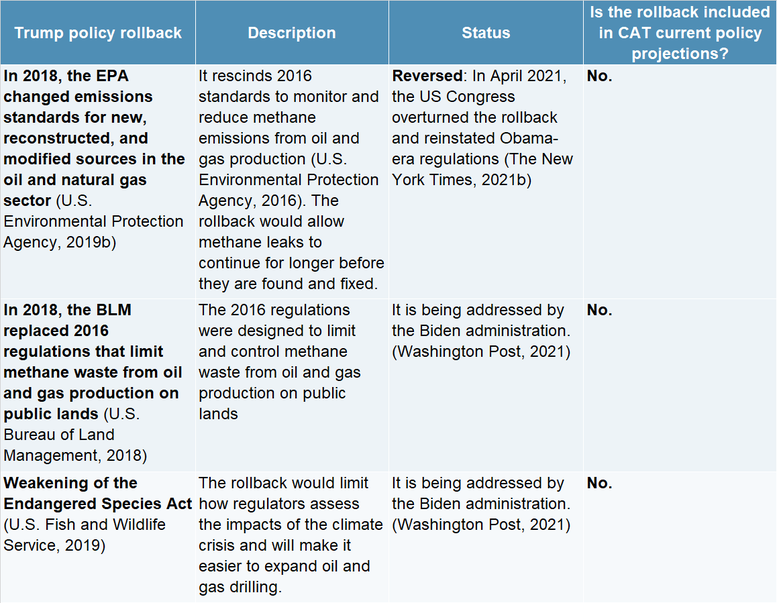

Reversing Trump-era policy rollbacks

On his first day in office, President Biden signed executive orders revoking previous executive orders of former President Trump deemed as a threat to the Government’s ability to confront climate change and directs all agencies to review and rescind the climate rollbacks of the previous four years (The White House, 2021b, 2021k). The following table presents the status of selected rollbacks in oil and gas extraction.

Transport

In 2019, GHG emissions from the transport sector accounted for about 29% of total emissions in the US and, since 2017, has been the largest contributor in GHG emissions. This is explained by the increase demand for travel, where the average number of vehicle miles travelled (VMT) per passenger cars and light-duty trucks increased by 47.5% from 1990 to 2019 (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2021a).

Similar to other sectors, the lockdown and travel restrictions caused by the measures taken to cope with the pandemic severely impacted the US transport sector. Energy-related CO2 emissions fell by 15% in the transportation sector in 2020 relative to the previous year, largely because of restricted travel, working from home and reduced commuting (Rhodium Group, 2021b; U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2021e).

Passenger transport

President Biden has signalled his intention to push for cleaner mobility, focusing on the electrification of light-duty passenger vehicles (LDV). As part of his plans to accelerate the adoption of cleaner vehicles, the President Biden set a goal to make 50% of all new vehicles sold in 2030 zero-emissions vehicles, including battery electric, plug-in hybrid electric, or fuel cell electric vehicles (The White House, 2021h). The target was backed up by major automakers including Ford and General Motors, which in a joint statement, announced their “shared aspiration” to achieve sales of 40%-50 % electric vehicles by 2030.

This goal is not aligned with the Paris Agreement. The CAT indicates that to be compatible with the Paris Agreement, 95%-100% of sales of new light-duty vehicles (LDV) in the US should be zero-emissions at the national level by 2030. Under current policies, however, it is projected that by 2030 just 9%-25% of LDV sales will be electric (Climate Action Tracker, 2021c).

Current plans and policies to decarbonise the US road transport sector are insufficient to reach Biden’s target by 2030, let alone to meet the 1.5°C Paris Agreement temperature goal.

US electric vehicles reached 2% of new vehicle sales in July 2018 (Kane, 2018), an average that dipped slightly to 1.9% in 2020 (Edmunds, 2021) but this is expected to increase to 2.5% in 2021 thanks to a larger selection of EV options and growing consumer interest. Platts Analytics estimates that the cumulative number of EVs in the United States displaced the use of 36,000 barrels per day of gasoline, up 19% from 2019 and is expected to grow steadily (Ryser, 2021).

In August 2021, the Biden administration took initial regulatory steps to erase the rollback of Trump-era greenhouse gas emission (GHG) emissions and fuel economy standards for passenger vehicles and propose stricter standards. The proposal sets GHG standards that would increase in stringency from model years (MY) 2022 to MY 2023 by 10%, followed by a nearly 5% stringency increase in each MY from 2024-2026. This proposal would significantly strengthen current standards, which are only 1.5% more stringent each year. Given the lead time for automakers to conform to the proposed standards, the emissions standards remain unchanged for the MY 2021-2022 (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2021g).

The proposed emissions standards are aiming for fleet average of 52 miles per gallon (mpg) by 2026, slightly more stringent than levels that existed under President Obama (50.1 mpg by 2025) but weakened in 2020 under the Trump administration (43.3 mpg by 2026). The new rules accounted for California’s ZEV mandate (and its adoption by a number of other states) in developing the baseline for the proposal, and has also accounted for the Framework Agreements between California, BMW, Ford, Honda, VWA, and Volvo. However, these rules are rather an attempt to reinstate the Obama-era standards, and might not be ambitious enough to put the US on the pathway to meet its sectoral and emission reduction targets by 2030.

In a departure from the approach taken by the previous administration, the proposed rule also contains an extensive cost-benefit assessment in terms of emissions savings, monetary saving accounting for pollution and health damage and an estimation of climate relevant indicators such the impact of the rules on global temperature by the end of the century and increase in sea level. The proposal estimates that roughly 2 GtCO2 of cumulative emissions would be avoided through 2050 compared to current standards. In annual terms, the estimated impact is 46 MtCO2 of avoided emissions in 2030 and 109 MtCO2 in 2050, or 2.5% and 6% of carbon emissions from the transport sector in 2019, respectively.

The final rule is expected to be issued by end of the year and stricter standards are expected for future models beyond MY 2026.

Current federal tax credits provide a USD 7,500 subsidy towards the purchase of an electric vehicle for the first 200,000 sold, these are often further complemented by manufacturer incentives (Electrek, 2021). The Biden climate plan included incentives to develop electric automobile industry and infrastructure, including public investment in half a million electric vehicle charging stations. President Biden also initiated a process to make use of the federal purchasing power to spur clean energy in the sector and replace the entire federal vehicle fleet with zero-emissions models, but has not yet provided a timeline for its implementation (J. Biden, 2020; The White House, 2021b).

The single most effective policy instrument at the federal level for the US transport sector to become 1.5˚C compatible would be a 2030 phase-out of fossil fuel light duty vehicle sales (Climate Action Tracker, 2021c). This is the kind of ambitious policy required across all sectors for the US to meet its new 2030 NDC and its 2050 net-zero target. This has been acknowledged by the US in its NDC, with a commitment to develop further policies over time.

Although there are no nationwide targets to ban the sale of new vehicles with internal combustion engines (ICE), much progress has been made at the non-federal level where states and automakers have set targets of 100% zero-emissions new vehicles sales by 2030-2035. The US states of Washington (2030), California (2035), and Massachusetts (2035) have also announced bans, and GM, one of the big three US manufacturers, recently pledged to only sell electric light duty (LDV) vehicles by 2035 (Associated Press, 2021; California Air Resources Board, 2021; Reuters, 2021c; Scientific American, 2021).

The new Transport Secretary outlined new priorities for the Department of Transport policy measures including particular attention paid to the climate impact of policies (Bort, 2021). One cited example was the promotion of walkable and bikeable “complete streets” to encourage modal shift, a measure that he has promoted as mayor of South Bend, Indiana (Duncan, 2021).

The Department of Transport will collaborate with the Department of Housing and Urban Development to encourage modal shift and transit-oriented development, with an emphasis on access to public transport. This implies that there would be a shift to not only focussing on fuel-efficiency standards and tailpipe emissions but also actively promoting modal shifts, electric vehicles through public procurement, tax credits, and support for charging infrastructure.

Freight transport

The Heavy-Duty Vehicle National Program sets greenhouse gas emissions and fuel efficiency standards for heavy-duty vehicles, which the EPA estimates will reduce emissions by 200 MtCO2/year by 2050 (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency & U.S. National Highway Safety Administration, 2016). To be compatible with the Paris Agreement’s long-term goal, freight trucks need to be almost fully decarbonised by around 2050 (Climate Action Tracker, 2018).

At state level, California passed a rule that requires warehouses operators to slash emissions from trucks, which would curb diesel emissions from trucks and spur electrification of freight trucks. The options in the rule to reduce or offset emissions include replacing diesel trucks with ZEVs trucks, installing zero-emissions charging or fuelling infrastructure (e.g., electric charger, hydrogen fuel stations) or installing onsite clean energy systems such as rooftop solar panels (South Coast Air Quality Management District, 2021).

Policies on shipping and aviation are not clear. Notably, for aviation, the White House’s statement outlined “the development and deployment of high integrity sustainable aviation fuels and other clean technologies that meet rigorous international standards, building on existing partnerships”, as well as the intention to work with partners in the International Maritime Organization and participating in ICAO’s offsetting scheme, CORSIA (The White House, 2021g)

Economic recovery

The USD 1tn Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act passed by the US Senate in August 2021 has some components relevant to the decarbonisation of the transport sector, including investments to modernise roads and public transit and to boost the electric vehicle market (U.S. Senate, 2021b). However, funding in transportation fell by $263 billion compared with the original proposal (The White House, 2021i). The following elements are included in the legislation passed by the senate :

- USD 7.5bn to develop electric vehicle charging stations across the country. This represents the largest shrink from the original investment proposal of USD 174bn to strengthen the EV manufacturing industry, build half million EV chargers across the country by 2030, replace more than 50,000 diesel vehicles, electrify 20% of the school bus fleet and fully electrify federal fleet.

- USD 39bn to modernise public transit. This could be positive if it triggers modal shift to cleaner transportation modes (e.g., rail, buses, etc). This component was reduced from the original proposal of USD 85bn.

- USD 66bn to ‘climate-friendly’ passenger and freight railways. This component was reduced from the original proposal of USD 80bn.

- USD 110 bn to invest on roads, bridges and other transportation projects. Further investments in highway infrastructure may however further induce transport emissions.

- $7.5 billion for clean buses and ferries but is not enough to electrify about 50,000 transit buses within five years, as originally proposed.

- $25 billion for airports. This component was not modified with respect to the original proposal.

- The combination of new working from home policies implemented by many employers and the plan’s proposal to build high-speed broadband infrastructure (USD 66bn) to expand coverage may have a long-lasting impact on commuting behaviour.

- Research in climate science, innovation and demonstration projects, including electric vehicles, smart charging infrastructure were removed from the final plan passed by the Senate.

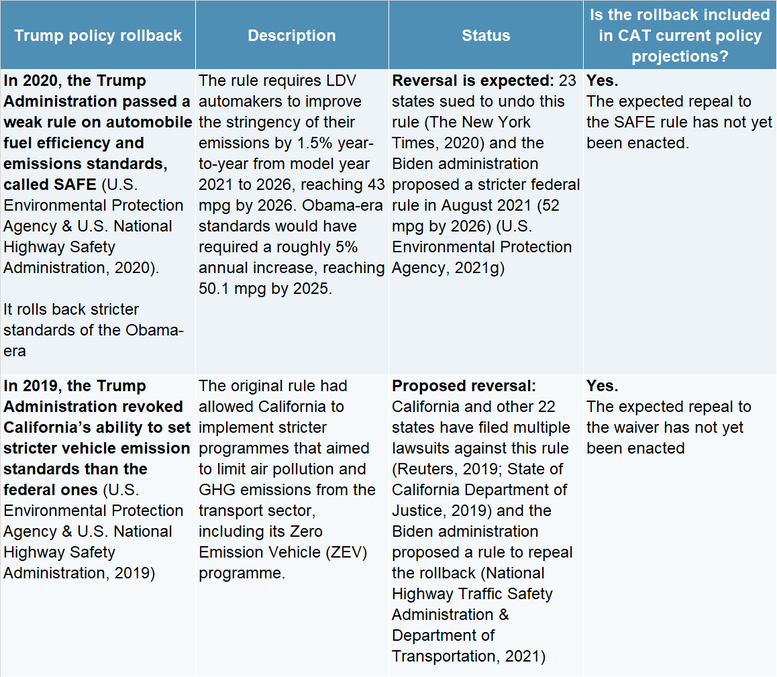

Reversing Trump-era policy rollbacks

On his first day in office, President Biden signed Executive Orders revoking former President Trump Executive Orders deemed to be a threat to the government’s ability to confront climate change, and directs all agencies to review and rescind the climate rollbacks of the previous four years (The White House, 2021b, 2021k). The following table presents the status of selected rollbacks in the transport sector.

An early measure of the Biden administration was to order US agencies to revisit the Trump Administration’s rollback of previous automobile fuel efficiency standards. The SAFE rule is the most significant regulatory rollback yet implemented and it would have been a major step backward in addressing the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the US. During the presidential election campaign, Biden had called for the establishment of “ambitious fuel economy standards”.

Undoing the Trump era rules is important because according to the official rule assessment, the rollback would have allowed cars to emit nearly 923 MtCO2 more over the lifetime of the vehicles produced between 2021–2026 than they would have emitted under the Obama-era standards (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency & U.S. National Highway Safety Administration, 2020). CAT calculations suggest that this could result in an increase in cumulative emissions of about 468 MtCO2e between 2020–2035. The Rhodium group estimates that if the administration reinstated the Obama-era fuel economy rules, combined with passage of a new law that would spend roughly $300bn over a decade on promoting electric vehicles, it could reduce 180 MtCO2 in 2031, roughly 11% of 2020 sector emissions (Rhodium Group, 2021a).

Notably, regardless of what happens on the federal level, a new Transport Department policy will reinstate California’s legal authority to set its own fuel economy standards (Puko & Restuccia, 2021). This has an impact beyond California because 13 other states and the District of Columbia, representing 31% of vehicles sales in the US, have adopted part or all of California’s tighter standards, including nine states that adopted Zero Emissions Vehicle targets (America’s Pledge, 2019)

Within the US, the state of California has been implementing ambitious policies for road transport for over 30 years and provides a demonstration of what is possible nationally with its Zero Emission Vehicle (ZEV) Program launched in 1990. California has continuously updated and expanded the policy over time, and its latest iteration requires 22% of LDV sales to be ZEVs by 2025.

It has implemented a slew of other supportive policies including its own tax credit in addition to federal subsidies, government fleet vehicle requirements, favourable highway and parking access, component replacement rebates and, in January 2021, an executive order to end the sale of internal combustion passenger vehicles by 2035. An aggressive expansion of California’s public charging network has ensured EV owners can easily travel throughout the state, alleviating the range anxiety that has previously acted as a perceived barrier to EV uptake (California Air Resources Board, 2018, 2021; California Code of Regulations, 2018; U.S. Department of Energy, 2021)

Several automakers representing more than one third of the US market share made a voluntary agreement with California at a compromise level of improving fuel efficiency standards by 3.7% per year through the model year 2026, which is stricter than the weak 1.5% improvement of the rollback but lower than the 5% annual increase originally agreed (Electrek, 2020).

Industry

Direct GHG emissions in the industry sector accounted for 23% of total US emissions in 2019, making it the third largest contributor to US GHG emissions after transport and electricity (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2021a).

In 2020, as a result of the slowdown in manufacturing operations due to responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, US greenhouse gases emissions in the industry sector dropped by 7% (Rhodium Group, 2021b) and energy-related CO2 emissions fell by 8% in the industrial sector (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2021e). Emissions from the combustion of coal fell by 15%, followed by an 8% and a 2% drop in emissions from consuming petroleum and natural gas, respectively. Electricity-related emissions in the industry sector also fell by 15% in 2020 compared to 2019 levels.

By Executive Order, President Biden directed his administration to ratify the Kigali Amendment which aims to phase down hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) worldwide. The US signed the amendment in 2016 in the last days of Obama administration but this was not ratified during the Trump presidency. Its ratification still requires the consent of the US Senate (NRDC, 2021a). HFCs are among the world’s most potent greenhouse gases, with warming potentials hundreds of times higher than CO2.

In December 2020, the US Congress enacted legislation to tackle HFCs as part of coronavirus relief, under the American Innovation and Manufacturing (AIM) Act. The AIM Act directs the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to address HFCs by providing new authorities in three main areas, to phase down the production and consumption of listed HFCs, manage HFCs and their substitutes, and facilitate the transition to next-generation technologies (U.S. Congress, 2020).

Accordingly, on May 19 2021, the EPA proposed a regulation that establishes the mechanism to achieve the objectives of the AIM Act and sets national limits on HFCs for the first time in the US. The proposed rule, which would take effect in 2022, aims to gradually reduce the production and imports of HFCs by 85% over the following 15 years after its implementation. The mechanism proposed in the rule is an allowance allocation and trading program, in which the allowances to companies will gradually decrease as the market for alternatives to HFCs grows. EPA also included in the assessment of the rule the health-related and climate change impacts of HFCs emissions (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2021c).

The EPA estimates that the rule would reduce emissions equivalent to 4.7 GtCO2e by 2050, nearly equal to three years of U.S. power sector emissions at 2019 levels. In 2036 alone, the final year of the proposed regulation, this rule is expected to prevent the equivalent of 187 MtCO2e. According to another study, the phase down of HFCs may be one of the most effective emission reduction measure taken in over a decade and has the potential to reduce emissions by 900 MtCO2e over the next 15 years (Rhodium Group, 2020).

The remaining 15% not covered by the rule is intended for critical uses of HFCs in industry where there are no alternatives. Although there is no single alternative that replaces all HFCs, there are alternatives to HFCs that are economically viable and with significantly lower global warming potential (GWP). The selection of an alternative depends on the specific application. For example, ammonia has the lowest GWP of all refrigerants and has strong synergies with green hydrogen production in an emissions-free economy. For domestic refrigeration, isobutane is a viable substitute, having been used to cool fridges in the EU, for example, for nearly three decades (Gschrey et al., 2018).

Economic recovery

The USD 1tn Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act passed by the US Senate in August 2021 (U.S. Senate, 2021b) left out all measures targeted to decarbonise the industry sector that were included in the original proposal presented by President Biden, including the following (The White House, 2021i):

- Reform and expand the bipartisan Section 45Q tax credit, which aims to support carbon capture and storage (CCS) in hard-to-abate industrial applications.

- Investment on clean energy research and demonstration projects of carbon capture retrofits for steel, cement and chemical production facilities.

A USD 3.5tn budgetary plan proposal, presented by the Democrats and intended to pass later this year through a budget reconciliation, is expected to contain many of the climate-relevant components that were left out of the bipartisan infrastructure plan. However, it is expected to face significant obstacles and it will likely not receive the bipartisan support of the infrastructure plan.

Reversing Trump-era policy rollbacks

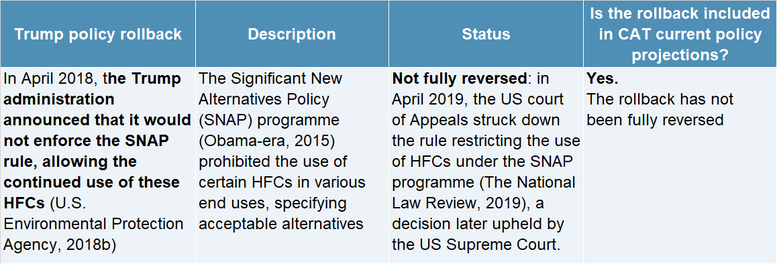

On his first day in office, President Biden signed Executive Orders revoking former President Trump’s Executive Orders deemed a threat to the Government’s ability to confront climate change and directs all agencies to review and rescind the climate rollbacks of the previous four years (The White House, 2021b, 2021k). The following table presents the status of selected rollbacks in the industry sector.

The original SNAP rule was estimated to reduce emissions by 54–64 MtCO2e/year in 2025 and by 78–101 MtCO2e/year in 2030 in comparison to a business as usual scenario (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2015). Note that the avoided emissions were estimated in 2015. By comparing current projections with the original business as usual scenario that was used as reference to quantify the impact of the policy, the CAT estimates that the emissions reductions are lower than initially anticipated: 30–35 MtCO2e/year in 2025 and by 40–52 MtCO2e/year in 2030.

More than a dozen states have either banned HFCs or restricted their use. California, Vermont and Washington have adopted measures to backstop the SNAP rollback within their own jurisdictions, which were followed by announcements from New York, Maryland, Connecticut and Delaware which plan to adopt similar measures (World Resources Institute, 2020).

The new administration has partly addressed the 2018 rollback. In May 2021, the EPA published a rule that expands the list of substitutes for refrigeration and air conditioning HFCs. However, the rule does not address the court’s decision that issued a partial vacation of the 2015-rule ‘‘to the extent it requires manufacturers to replace HFCs with a substitute substance’’ (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2021d). The court decision allows the continued use of these HFCs.

Buildings

In 2019, direct greenhouse gas emissions from buildings accounted for 13% percent of total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, with 7% from commercial buildings and 6% from residential. Direct GHG emissions in buildings have remained relatively constant in the last decades, increasing 8% between 1990–2019. (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2021a).

The economic slowdown and the restriction measures resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic impacted energy consumption and emissions in the buildings sector in 2020. Although electricity consumption increased in 2020, mainly in the residential sector due to restricted mobility and working from home, the emissions associated with energy use in the commercial and residential sectors fell by 12% and 6% in 2020 respect to the previous year. This is a consequence of lower carbon intensity of the electricity grid due to higher share of renewable sources and the lower presence of coal in the energy mix (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2021e).

The US has numerous federal and state level policies in the building sector, primarily focused on energy efficiency. These policies include the National Appliance Energy Conservation Act of 1987, with appliance standards that were updated in 2015, and the Energy Policy Act of 1992 and 2005, which includes whole house efficiency minimums. The EPA runs the Energy Star programme, which uses a voluntary labelling system to increase consumer awareness of energy efficiency (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy, 2019).

The US does not have federal targets for constructing net zero energy buildings (nZEBs), although California and Massachusetts do. This is in contrast to the EU, for example, which requires all new buildings to be “near” nZEBs starting in 2021 (European Commission, 2020). For Paris Agreement-compatibility, all new buildings globally should be nZEBs starting in 2020, and renovation rates should increase to 3%–5% per year (Climate Action Tracker, 2016a).

The CAT estimates that to be Paris compatible, emissions from the US buildings should be around 60% lower in residential buildings and 70% lower in commercial buildings than in 2015 (Climate Action Tracker, 2021d, 2021b).

Economic recovery

The USD 1tn Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act passed by the US Senate in August 2021 (U.S. Senate, 2021b) left out all measures targeted to decarbonise the building sector that were included in the original proposal presented by President Biden. The original plan called for USD 213bn investment to improve commercial and residential buildings, USD 137bn investment in public buildings and the following complementary measures (The White House, 2021i):

- Build and retrofit more than two million housing units with a focus on energy efficiency and electrification.

- Investments on improving energy efficiency and electrification to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases from public buildings: USD 100bn to upgrade and build public schools, USD 18bn to modernise public hospitals, and USD 10bn to modernise federal buildings.

- USD 20bn in tax credits to build and rehabilitate more than half million housing units

- USD 40bn to improve public housing, including measures in enhance energy efficiency

- Establish a USD 27bn Clean Energy and Sustainability Accelerator to mobilise private investment into distributed energy resources, retrofits of residential, commercial and municipal buildings, and clean transportation

A USD 3.5tn budgetary plan proposal, presented by the Democrats and intended to pass later this year through a budget reconciliation, is expected to contain many of the climate-relevant components that were left out of the bipartisan infrastructure plan. However, it is expected to face significant obstacles and it will likely not receive the bipartisan support of the infrastructure plan.

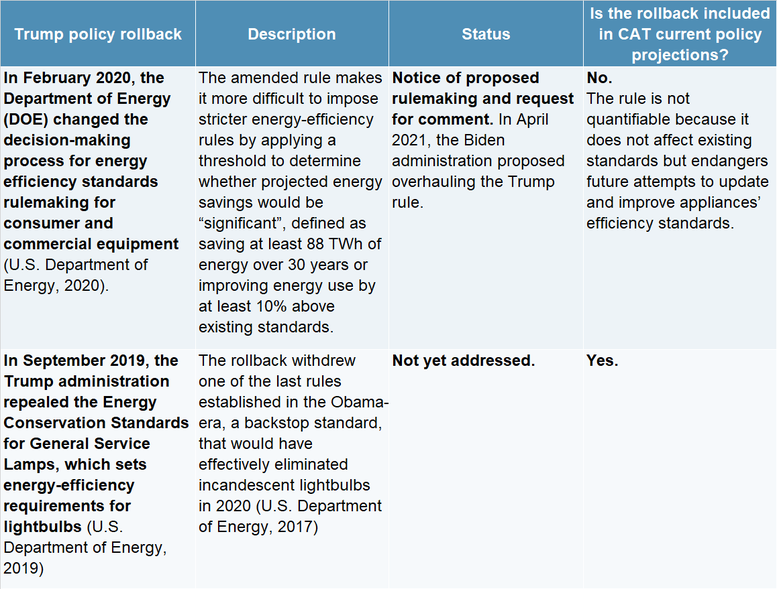

Reversing Trump-era policy rollbacks

On his first day in office, President Biden signed Executive Orders revoking former President Trump Executive Orders deemed to be a threat to the Government’s ability to confront climate change and directs all agencies to review and rescind the climate rollbacks of the previous four years (The White House, 2021b, 2021k). The following table presents the status of selected rollbacks in the buildings sector.

Agriculture

Greenhouse gas emissions from the agriculture sector made up 10% of national emissions in 2019, which increased by about 11.5% percent since 1990 (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2021a).

In its updated Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) the US commits to reduce emissions from forests and agriculture and enhance carbon sinks through a range of programmes and measures for ecosystems ranging from forests to agricultural soils. Actions mentioned in the NDC include, for example, reducing emissions and sequestering more carbon dioxide by scaling up support to climate smart agricultural practices (e.g., cover crops, rotational grazing, and nutrient management practices) (US Government, 2021).

In one of the Executive Orders, “Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad”, the Biden administration explicitly mentions measures in agriculture to address climate change. It requests the Secretary of Agriculture to submit recommendations for an agricultural and forestry climate strategy and to create a Civilian Climate Corps initiative to conserve and restore public lands and waters, increase reforestation, promote carbon sequestration in the agricultural sector and the sourcing of sustainable bioproducts and fuels (The White House, 2021b).

Accordingly, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) is developing a climate-smart agriculture and forestry strategy and plans to engage with a range of stakeholders to explore opportunities to encourage the voluntary adoption of “climate-smart” agricultural and forestry practices.

The Growing Climate Solutions Bill was reintroduced in April 2021 in the US Senate. The US Senate passed the bill in June 2021, and it still has to be passed by the House of Representatives (U.S. Senate, 2021a). The bill directs the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) to provide technical assistance and certification programme to remove barriers and assist producers and forest owners seeking to participate in voluntary carbon markets and be rewarded for climate-smart practices. This initiative aims to create new sources of income for agricultural activities tied to climate practices. The act, which has bipartisan support in the House of Representatives and the backing of major agricultural lobbies, has a good chance of becoming law.

The US Department of Agriculture (USDA)’s “Building Blocks for Climate Smart Agriculture & Forestry” foresees a set of voluntary activities involving farmers and companies. The Obama-era measures targeted reductions in emissions from agriculture (e.g. improved fertiliser use and other agricultural practices, avoiding methane from livestock) and land use and forestry (e.g. improved soil management, avoid deforestation and reforestation) (The White House, 2016a).

Forestry

Historically, the LULUCF sector has been a net sink for greenhouse gas emissions in the US, ranging between 0.6 and 0.8 GtCO2e annually between 1990 and 2019, although forest fires exacerbated by drought and extreme weather events such as heat waves have been a growing source of emissions from managed forests.

In the submission of the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) the US commits to reduce emissions from forests and agriculture and enhance carbon sinks through a range of programs and measures for ecosystems ranging from forests to agricultural soils.

Actions mentioned in the NDC include, for example, that federal and state governments will invest in forest protection and forest management, and engage in intensive efforts to reduce the scope and intensity of wildfires, and to restore fire-damaged forest lands. Alongside these efforts, the US will support nature-based coastal resilience projects including pre-disaster planning as well as efforts to increase sequestration in waterways and oceans by pursuing “blue carbon” (US Government, 2021).

In October 2019, the government proposed reversing a long-standing rule that limits logging in the largest national forest, Alaska’s Tongass National Forest (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2019). The proposed rule would open up nearly half of the 16.7 million-acre Tongass National Forest to logging, reducing the sinks from forestry and land use. A broad coalition of Indigenous groups, local businesses, and environmental organisations sued to block the rollback (NRDC, 2021b).

Waste

The EPA finalised standards to reduce methane emissions from new, modified, and reconstructed municipal solid waste landfills in 2016. In August 2019, the EPA passed a rule to amend the standards, postpone the compliance period, and postpone the due date for state plans to limit methane emissions from landfills (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2019a). This could mean increased emissions from landfills in the future.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter