Policies & action

Policies and action rating

The CAT rates the US’ policies and actions as “Highly Insufficient.” The “Highly Insufficient” rating indicates that US policies and action in 2030 are not at all consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C. If all countries were to follow the US approach, warming could reach over 3°C and up to 4°C.

The CAT projects GHG emissions under current policies, partially accounting for the impact of OBBB, will reach between 5.2–6.1 GtCO2e in 2030 and 4.5–5.7 GtCO2e in 2035 (excluding emissions from land use, land use change and forestry, or LULUCF). Emissions will be reduced by 19%–30% in 2030 and 24%–41% in 2035 from 2005 levels (excl. LULUCF).

In comparison to the CAT’s last policy projections, which considered all major climate policies enacted under the Biden Administration, emissions under the Trump Administration are projected to be 14%–15% higher in 2030 and 13%–18% higher in 2035 (excl. LULUCF).

The Trump Administration implemented the most aggressive, comprehensive, and consequential executive and legislative rollback of climate policies and actions that the Climate Action Tracker has ever analysed. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBB), passed in 2025, represents a significant setback for US climate policy. The OBBB undoes much of the potential of the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). The IRA mobilised historic investment in clean energy, driving clean energy technology deployment, creating hundreds of thousands of jobs, and attracting private sector funding. Under the direction of the Trump Administration, the EPA began the process of repealing emissions standards for the power and transport sectors, which were strengthened in 2024.

Further information on how the CAT rates countries (against modelled domestic pathways and fair share) can be found here.

Policy overview

Our analysis shows the Trump Administration’s policies and actions are not at all compatible with limiting warming to 1.5°C.

Compared to CAT projections from November 2024, the latest emission projections consider the passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBB), as well as the likely rollback of the US Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) emissions regulations for the power and transport sectors. As a result of these policy developments, the US’ emissions projections increased significantly relative to the CAT’s previous projections.

President Trump signed the OBBB into law in July 2025. The OBBB rolls back most of the tax credits for clean electricity, fuels, vehicles, and industry introduced and expanded by the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). The OBBB will significantly slow the deployment of renewable energy: cumulative capacity additions for wind and solar will be halved by 2035 compared to levels projected under the Biden Administration.

The OBBB will also substantially curb demand for EVs and, in doing so, undermine automakers' investment decisions in domestic EV and battery manufacturing that were supported by IRA. Prior to the OBBB’s passage, the IRA was set to inject USD 370bn into the US economy until 2032 and, in doing so, mobilised historic private investment in the US energy transition, accelerating the buildout of renewable energy, and the production and adoption of clean energy technologies.

Under the direction of the Trump Administration, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) used contentious scientific evidence to propose the rescission of the 2009 Endangerment Finding, which serves as the EPA’s legal basis for regulating GHG emissions. If the EPA revokes the finding, the agency will no longer enforce emissions standards in the power, transport, industry, and methane sectors.

Alongside its proposal to revoke the Endangerment Finding, the EPA is reconsidering its vehicle emissions standards for passenger cars, light-duty trucks, and medium-duty vehicles, which were strengthened under the Biden Administration. The standards were made more stringent in 2024 and would have resulted in auto manufacturers producing 30%–56% battery electric vehicles in 2032. The EPA has also proposed repealing all GHG emissions standards for fossil fuel-fired power plants.

The Trump Administration seeks to limit subnational efforts to reduce emissions. The administration directed the US Department of Justice (DOJ) to identify and challenge all state laws that “address ‘climate change’ or involve ‘environmental, social, and governance’ initiatives, ‘environmental justice,’ carbon or ‘greenhouse gas’ emissions, and funds to collect carbon penalties or carbon taxes.”

Power sector

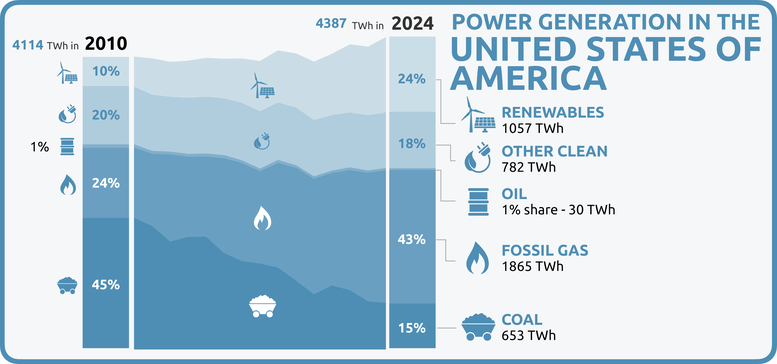

The power sector contributed 25% of total US GHG emissions in 2022 (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2024c). Total annual emissions in the power sector have declined steadily since 2010, mainly driven by a shift from coal to fossil gas and renewables. The Trump Administration—which has abandoned the Biden Administration’s target for a carbon-free electricity system by 2035—aims to prolong coal power generation, expand fossil gas power generation, and reduce renewable power generation. The administration’s policies and actions in the power sector will substantially decelerate emission reductions.

Electricity production from renewables overtook production from coal and nuclear power for the first time in 2022, making renewables the country’s second largest source of electricity generation after fossil gas (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2023c). Coal has now become the least relevant generation source in the US.

The Trump Administration declared a national energy emergency in January 2025, under which it directs all federal agencies to expedite the development of energy production and generation capacity (The White House, 2025a). The national energy emergency appears to be a pretext for expanding fossil fuels, as the declaration applies to the expansion of all domestic fossil fuel sources but not to wind and solar.

Growth in electricity demand is driven by the emergence of large-scale data centres, the increase in manufacturing facilities, the enhanced demand for building cooling and heating, and the introduction of hydrogen fuel plants. For instance, electricity demand from data centres, which currently account for around 4% of electricity demand, is expected to grow to between 4.6%-9.1% of electricity demand by 2030 (Electric Power Research Institute, 2024).

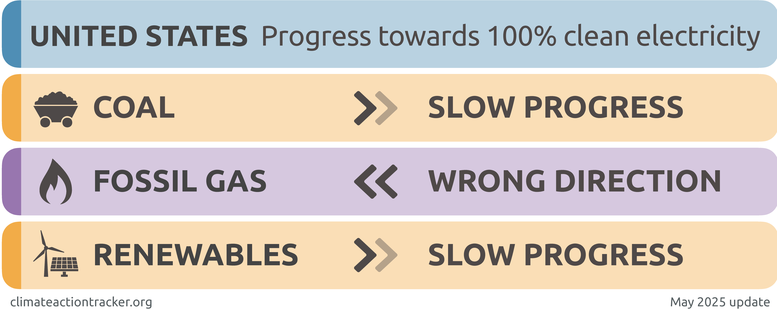

Renewables

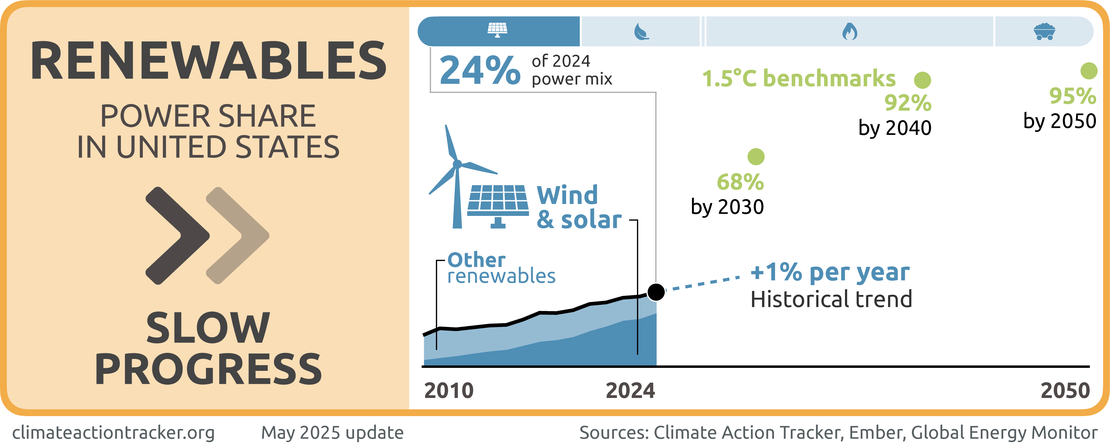

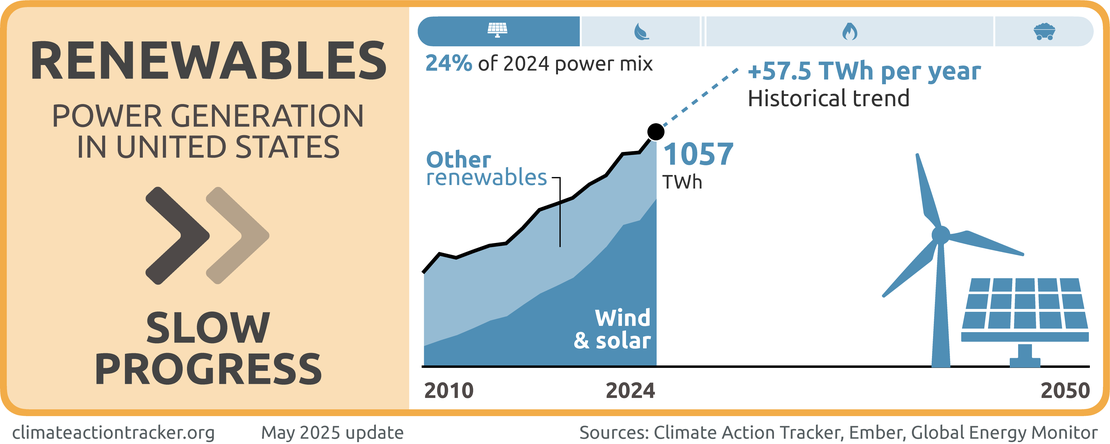

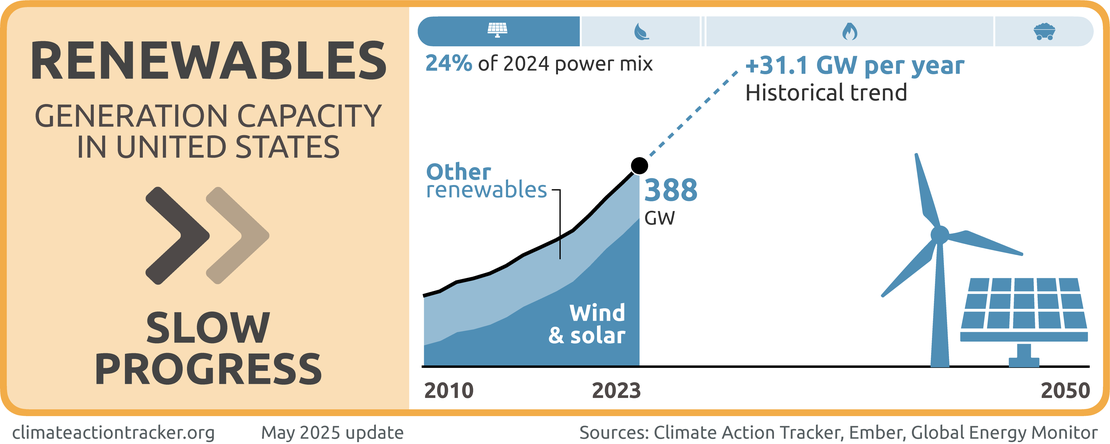

The US making “Slow Progress” on deploying renewables. Although the share of renewables in US electricity generation has gradually increased in recent years and accounted for approximately 24% of total US electricity generation in 2024, the outlook for renewable energy has severely worsened under the Trump Administration, which has initiated executive and legislative actions that obstruct deployment of renewables in favour of fossil fuels (Ember, 2025).

The OBBB will substantially slow the deployment of renewables, especially wind and solar. The Trump Administration has acted to restrict wind development on federal land and revoke approval for wind projects under active construction.

Under the Biden Administration, increasingly cost-competitive renewables, in combination with federal- and state-level measures, resulted in renewables accounting for over 90% of new generation capacity in the US in 2024 (Energy Innovation, 2025). The deployment of renewables still needs significant acceleration over the next three decades to be compatible with 1.5°C. To align with 1.5°C, the share of renewables in the US would need to increase to 68% by 2030, to 92% by 2040, and to 95% by 2050.

Renewable energy incentives

The OBBB modifies federal tax credits for utility-scale renewable energy deployment that are expected to particularly reduce the buildout of wind and solar energy in the US over the next decade. The OBBB makes several changes to the Clean Electricity Production Tax Credit (PTC) and the Clean Electricity Investment Tax Credit (ITC)— introduced by the IRA as technology-neutral, emissions reductions-based incentives for domestic clean energy development—that specifically restricted access for new wind and solar projects from 2026.

To qualify for the PTC and ITC, new wind and solar facilities must begin construction before July 2026 and must enter service by the end of 2027. Before the OBBB’s passage, wind and solar projects that commenced construction in 2026 had until 2030 to operationalise. The OBBB introduces complex prohibited foreign entity (PFE) restrictions for the PTC and ITC, which seek to limit the involvement of certain foreign companies, including Chinese companies. Coupled with the accelerated phase-out of the credits, the PFE rules present an additional barrier for developers to construct and operationalise new wind and solar capacity by 2027. For non-wind and solar renewable energy sources—notably, geothermal and hydropower—the PTC and ITC are preserved until 2033 without modification (Cockerham et al., 2025).

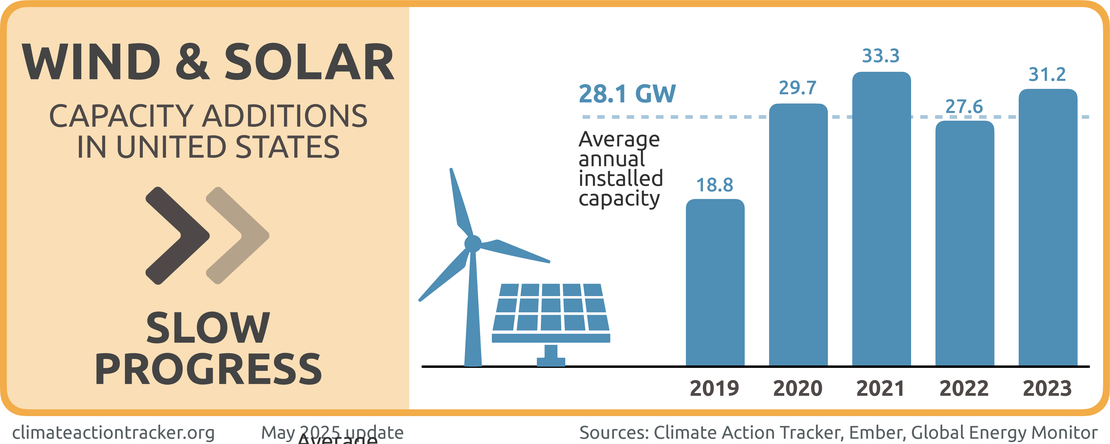

The OBBB’s changes to the PTC and ITC sabotage the pipeline for wind and solar projects that emerged following the IRA’s enactment. Research suggests that the OBBB will more than halve annual average wind and solar capacity additions through 2035 in comparison to before its enactment; cumulative solar and wind generation capacity additions will be reduced by approximately 300 GW by 2035 (Jenkins et al., 2025). Between 2019 and 2023, installed solar and wind capacity increased by an average of 28 GW per year (Ember, 2025). Before the OBBB’s enactment, installed wind and solar capacity was forecasted to accelerate significantly and increase to an average of nearly 70 GW per year until 2035 (Jenkins et al., 2025).

Beyond targeting tax credits for utility-scale wind and solar projects, the OBBB terminates tax credits for distributed, residential wind and solar deployment. The Act phases out the Residential Clean Energy Credit at the end of 2025 (IRS, 2025b). The credit, which was expanded by the IRA and was set to expire in 2033, reduced the cost of installing residential solar panels and wind turbines, as well as geothermal heat pumps and battery storage solutions (IRS, 2025c).

The OBBB also targets domestic manufacturing for wind energy components. In 2028, wind energy components will no longer be eligible for the Advanced Manufacturing Tax Credit, which will likely result in constrained supply chains for domestically manufactured wind energy components (Lorch et al., 2025). Coupled with the OBBB’s strict PFE restrictions for wind energy development, the restricted supply of US-made wind energy components will only further obstruct wind deployment.

Renewable energy permitting

The Trump Administration has taken several steps to hamper the buildout of solar and wind, especially offshore wind, on federal lands and waters. In January 2025, the US Department of the Interior (DOI) paused approvals for new renewable energy developments on federal lands and waters (U.S. Department of the Interior, 2025b). Research estimates that federal lands offer potential for 5,750 GW of utility-scale solar energy and 875 GW of land-based wind energy (Mai et al., 2025).

In May 2025, the DOI proposed to increase fees for new solar and wind projects on federal lands and waters, which were decreased by the Biden Administration to encourage greater variable renewable energy deployment. In July 2025, the DOI introduced new centralised, bureaucracy-intensive review procedures for approving new wind and solar projects on federal lands. The review process will likely result in significant project delays and introduce additional uncertainty for investors (Slack and Johnson, 2025). Jointly, the DOI rule changes create a policy environment that will deter wind and solar development in the US.

The Trump Administration is reviewing and, in some cases, revoking permits for offshore wind developments that were issued under the Biden Administration, creating significant uncertainty and risk for project developers. As of September 2025, Trump Administration has halted construction of three offshore wind developments. Most notable is the case of Revolution Wind, a USD 6bn wind energy project that was 80% completed when the Trump Administration revoked its permit. In August 2025, the US Department of Transportation (DOT) pulled nearly USD 700m in federal funding for offshore wind projects (U.S. Department of Transportation, 2025).

Before the Trump Administration, permitting and siting were already major barriers for the buildout of renewable energy capacity. Current project build times average four years. The IRA included USD 1bn through the Permitting Action Plan, which sought to accelerate the federal permitting and environmental review process for transmission lines and clean energy production. In addition to complex permitting processes, renewable energy developers continue to face higher interest rates, outdated transmissions infrastructure, and thin supply chains (Bird and Womble, 2024).

State-level efforts for renewable energy deployment

States can play an important role in facilitating the buildout of renewable energy. At the state level, renewable portfolio standards (RPS) and clean energy standards (CES) have been major drivers for growth in renewables. In total, 35 states have enacted RPS or CES legislation (Climate XChange, 2025). Of these, 15 states and D.C. have signed 100% clean electricity goals into legislation, while seven states have enacted such a target through state-level executive orders (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2023d).

States oversee permitting and siting processes within their jurisdiction. California and Massachusetts have implemented promising approaches for streamlining the permitting process for clean energy projects that could be replicated by other states (Bird and McLaughlin, 2023).

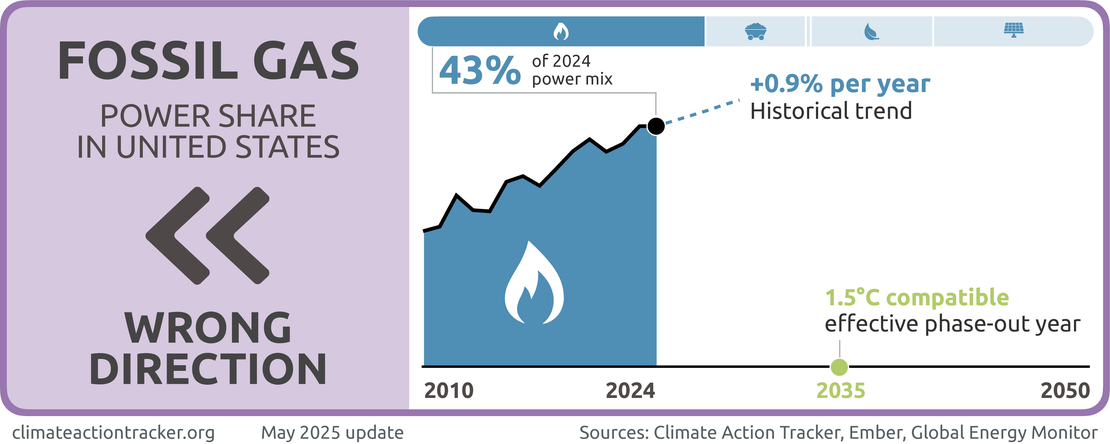

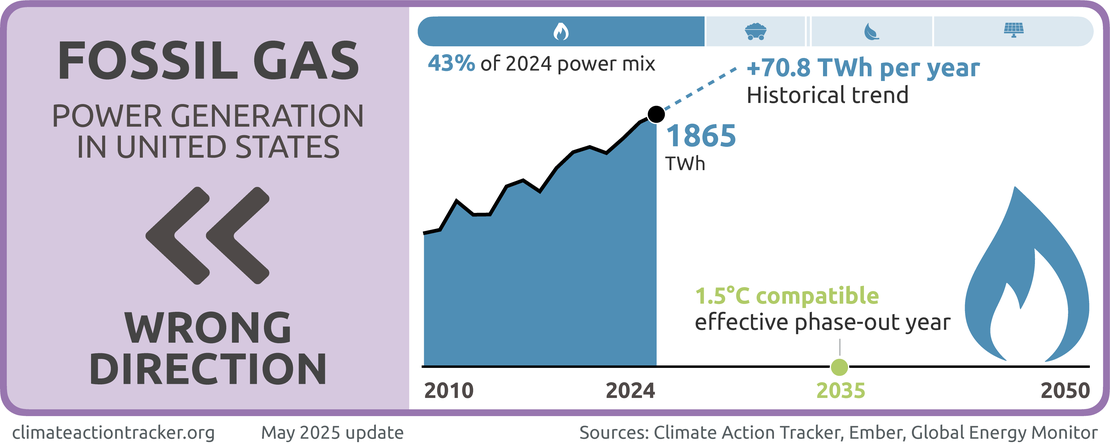

Fossil gas

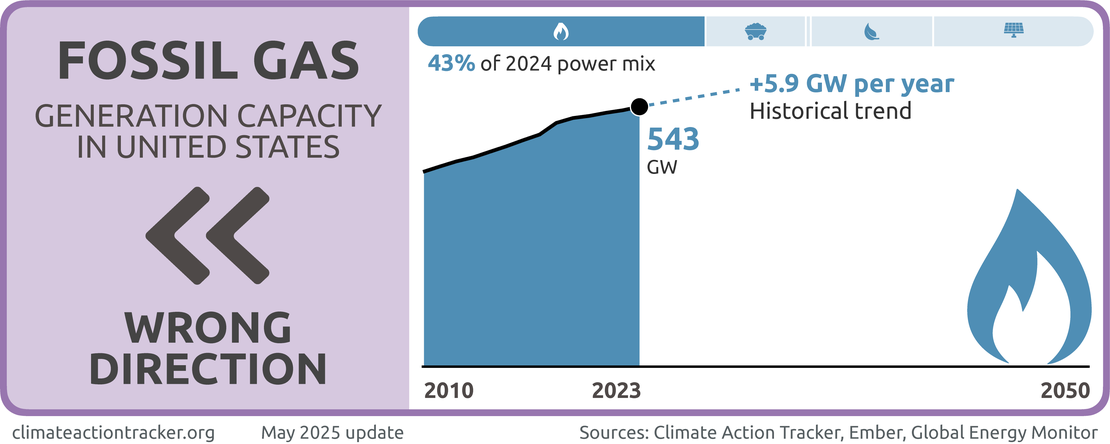

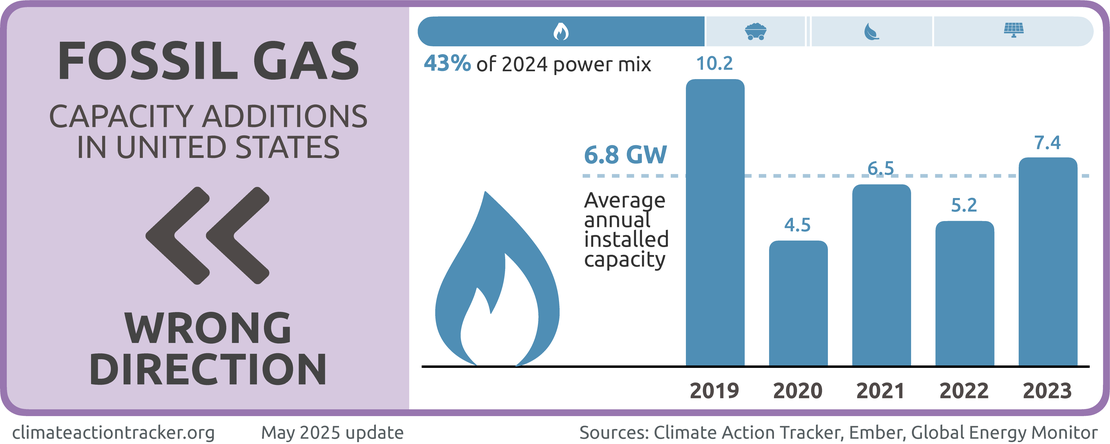

The US is headed in the “Wrong Direction” on fossil gas. In 2024, fossil gas was the largest source of electricity, generating 43% of all electricity (Ember, 2025). Under the Trump Administration, the US is poised to accelerate the expansion of fossil gas generation capacity, which was already increasing under the Biden Administration.

Emissions standards for fossil gas-fired generation

Under the direction of the Trump Administration, the EPA proposed repealing all GHG emission standards for fossil fuel-fired power plants in June 2025 (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2025f). The proposal would overturn the Carbon Pollution Standards to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Power Plants (CPS), revised by the Biden Administration in 2024 (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2024a). The standards apply to new and reconstructed fossil gas-fired power plants and mandate such plants to capture 90% of emitted CO2 using carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies by 2032.

Pipeline for new fossil gas-fired generation

Under the Trump Administration, the pipeline for additional fossil gas generation capacity has more than doubled (Maguire, 2025). As of August 2025, the US is developing more gas plants than any other country: over 160 GW of new fossil gas capacity is under development, which will result in additional emissions of 265 MtCO2 per year on top of the current gas plant fleet’s emissions of over 900 MTCO2 per year (Global Energy Monitor, 2025b). In addition to 543 GW of existing fossil gas generation capacity, at least 80 GW of new fossil gas generation capacity is expected to be operational by 2030 (Shenk, 2025).

To be 1.5°C compatible, the US needs to phase out fossil gas by 2035. However, research suggests that the lifetime use for fossil gas-fired plants breaks even after 9–17 years of operation. The longevity of gas-fired power plants jeopardises the US ability to phase out fossil gas by 2035 and, therefore, invites the deployment of CCS.

It is important to note that CCS technologies are neither commercially viable nor proven at scale, despite large public subsidies for research and development globally. Heavily relying on unproven CCS for power generation simply prolongs the use of fossil fuels, diverting attention and resources away from the necessary and urgent transition to renewable energy generation that drives down emissions.

The use of CCS should be limited to industrial applications where there are fewer options to reduce process emissions—not to reduce emissions from the electricity sector where renewables are cost-effective mitigation alternatives, not least because CCS does not remove 100% of emissions from power plants.

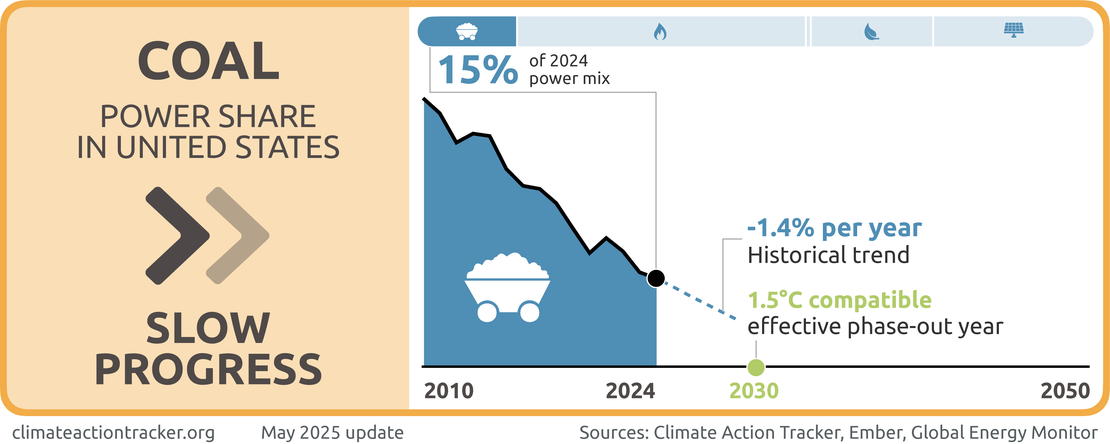

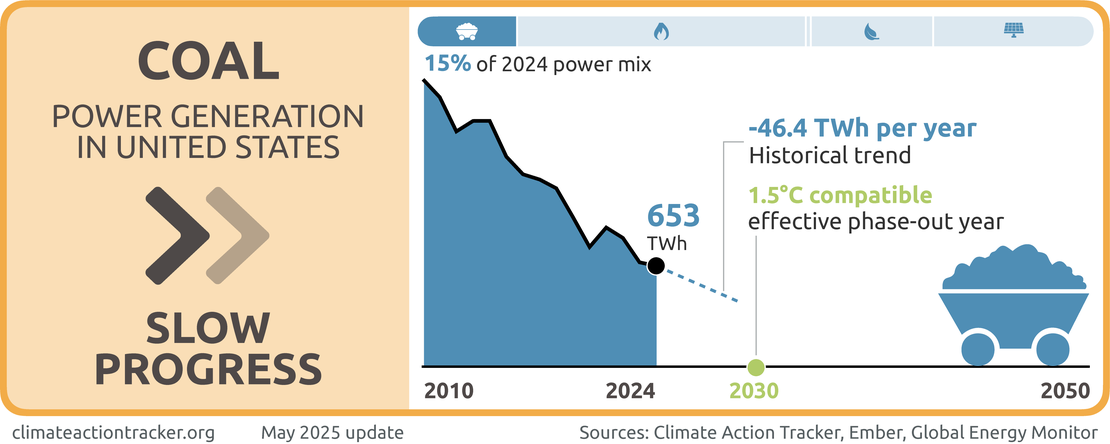

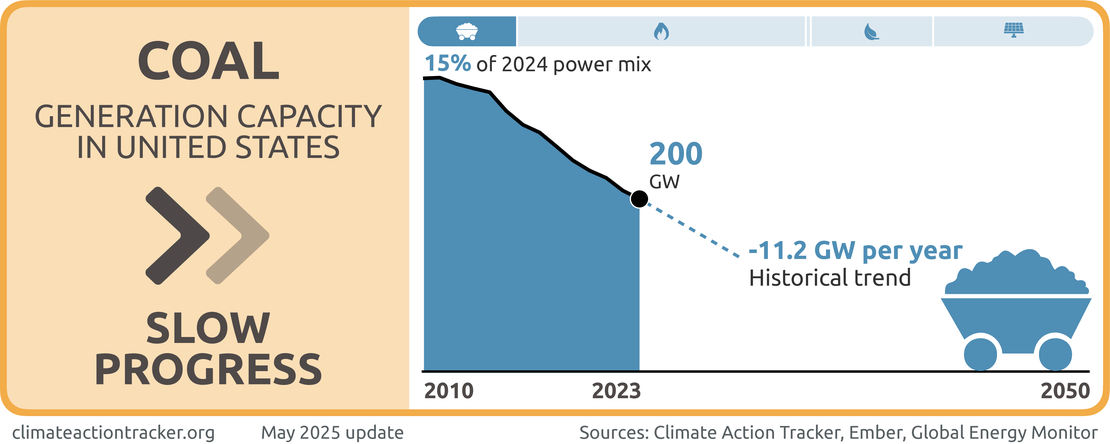

Coal

The US is making “Slow Progress” on reducing the share of coal in its power mix. For the past five years, the share of coal in electricity generation has decreased by 1.4% per year (Ember, 2025; Global Energy Monitor, 2025b). The decline is largely the result of the increasingly unfavourable economics of coal generation amid the buildout of fossil gas and renewable generation. In an attempt to counteract market forces, the Trump Administration is mounting a policy push to prolong the use of coal for power generation in the US.

Emissions standards for coal-fired generation

The EPA’s proposal to repeal all GHG emissions standards for fossil fuel-fired power plants would void the Carbon Pollution Standards to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Power Plants (CPS), which apply to existing and modified coal-fired power plants (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2024a, 2025f).

The CPS, strengthened by the Biden Administration in 2024, apply to existing coal-fired power plants that plan to operate beyond 2032. Plants that retire before 2039 must reduce emissions equivalent to co-firing 40% by fossil gas by 2030. Plants that operate beyond 2039 need to capture 90% of emitted CO2 using CCS by 2032. The CPS, if maintained, are expected to accelerate coal plant retirements until 2040, resulting in an additional 22 GW of coal-fired capacity going offline by 2035 (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2024d).

Legislative and executive actions on coal

The Trump Administration has taken a series of executive actions to expand domestic coal production and consumption. In April 2025, the Trump Administration lifted a ban on coal leasing on federal lands, expedited permitting processes for new coal mines on federal lands, reclassified coal as a strategically critical “mineral,” and instructed all relevant federal agencies to remove regulatory barriers for coal extraction and combustion. The administration seeks to prevent aging coal-fired power plants from retiring. The administration also exempted over 65 coal-fired power plants from EPA regulations on mercury and other toxic air pollutants.

The Trump Administration’s actions will likely extend the operating lifetimes of existing coal-fired power plants. In 2025, approximately 8 GW of coal-fired capacity, or 5% of the US coal fleet, is set to retire (U.S. Energy Information Agency, 2025). In comparison, annual coal retirements averaged 11 GW between 2015 and 2020 (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2023b). The OBBB offers additional incentives to the US coal industry. The Act mandates millions of acres of federal lands be used for coal mining and reduces the royalty rate for coal companies on federal lands.

However, even with the executive and legislative support, it is highly unlikely that new coal-fired generation capacity will be added. Since 2013, no new coal-fired capacity has been installed in the US, while 145 GW of coal-fired capacity has been retired (Global Energy Monitor, 2025a).

Oil and fossil gas extraction

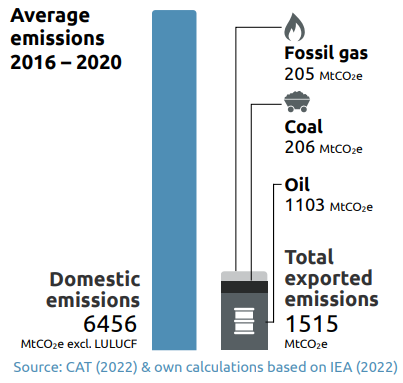

The US is the world’s largest oil and fossil gas producer

The US is the world’s largest producer of crude oil and fossil gas. Under the Biden Administration, the US reached unprecedented levels of oil and gas extraction. The Trump Administration is projected to further increase oil and gas production in 2025. Liquified natural gas (LNG) exports are expected to reach an all-time high in 2025.

Oil and fossil gas production and export volume

The US has been the world’s largest producer of crude oil since 2018 (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2018). US crude oil production is projected to reach an all-time high of 13.4m barrels per day in 2025 (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2025b). Increased production is driven by increased demand for US crude oil in Europe and Asia. In 2024, crude oil exports reached record levels, peaking at 4.1m barrels per day.

Refined petroleum product exports also reached an all-time high in 2024: 6.6m bpd were exported. Since 2020, growth in propane exports has driven growth in overall petroleum product exports; approximately 1.8 million barrels were exported per day in 2024 (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2025e).

The US became the world’s largest LNG exporter in 2022. LNG exports continue to increase year after year. Under the Trump Administration, the US is poised to increase liquified natural gas (LNG) exports by 25% in 2025 relative to 2024.

The growth in LNG exports has been driven by demand in Europe and Asia. In 2024, Europe accounted for over 50% of all LNG exports. In Asia, exports from the US continue to increase: the share of LNG exports to Asia increased from 26% to 33% from 2023 to 2024 (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2025d).

LNG export capacity additions

The Trump Administration lifted the Biden Administration’s pause on the development of new LNG export terminals in January 2025. The Biden Administration imposed a moratorium on new LNG export infrastructure in January 2024 (Daly, 2024). The pause did not impact operational or approved LNG terminals. The pause only affected one-quarter of planned LNG export capacity and, as a result, did not significantly impact US LNG export capacity, which is to double by 2028 (Rozansky, 2024). By the end of the Biden Administration, the US had eight operational LNG export terminals, while an additional five terminals were under construction (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2025c). As of May 2025, the Trump Administration granted permits to five new LNG export terminals (Baurick, 2025).

The US has some of the largest expansion plans for oil and gas projects in the world. The country accounts for over one-third of planned global expansion in oil and gas extraction between 2023 and 2050. With 22 oil and gas mega-project plans in place, the US accounts for more than one-fifth of potential emissions from major carbon emitting energy projects in the world. Together, these 22 mega-projects have the potential to emit nearly 143 GtCO2e in their lifetime, almost four times more than the entire world emits each year (Kühne et al., 2022). The planned US expansion of oil and gas projects is entirely incompatible with the goal of limiting warming to 1.5C.

Fossil fuel production subsidies

Direct and indirect federal subsidies for fossil fuels have and will continue to spur the expansion of fossil fuel projects in the US.

Research indicates that two of the largest and longest standing direct subsidies—the ‘expensing of intangible drilling costs’ (IDC) subsidy and the ‘percentage depletion’ subsidy—increased the expected value of new oil and gas projects by upwards of USD 20bn over the past two decades (Erickson and Achakulwisut, 2021).

The IRA reduced the IDC subsidy in 2022, but the OBBB reinstates the full IDC subsidy for oil and gas production. By restoring full tax deductibility for IDCs, the OBBB provides immediate tax relief and encourage further capital investment in oil and gas extraction.

Expansion of oil and gas projects is driven by planned increases in oil and gas fracking and LNG extraction(Ioualalen and Trout, 2023). In 2023, US subsidies for coal, natural gas, and petroleum producers, as defined as budgetary transfers, tax expenditures, and general supply and demand-side financial support, reached their highest level on record: subsidies amounted to USD 5.35bn in 2023 (Fossil Fuel Subsidy Tracker, 2025).

New fossil fuel auctions and project approvals

In January 2025, the Trump Administration reopened the entire Atlantic and Pacific coasts, as well as much of the Arctic Ocean, to offshore oil and gas drilling; coastal areas where the Biden Administration had previously barred oil and gas leasing (The White House, 2025c). During the first Trump Administration, a similar move was deemed unlawful in 2017, which may make oil and gas companies hesitant to engage in reopened waters (Frazin, 2025).

In response to the Trump Administration’s declaration of a national energy emergency, the US Department of Energy (DOI) updated its permitting procedures to accelerate review and approval for the development of certain energy sources on federal lands and waters (U.S. Department of the Interior, 2025a). The expedited permitting procedures apply to oil, gas, coal, and petroleum projects, but, notably, do not apply to wind and solar projects. The DOI’s new permitting procedures aim to cut a multi-year process down to a maximum of 28 days.

The OBBB requires oil and gas lease sales on certain federal lands and waters. The Act mandates at least 36 new oil and gas leases in the Gulf of Mexico and off the Alaskan coast until 2040. In doing so, the act overrides the Biden Administration’s stricter rules for offshore oil and gas leasing from 2023 (Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, 2023). The OBBB also reduces royalty rates for oil and gas exploration and production, which were increased under the IRA.

Before the OBBB’s passage, the IRA provided concessions to the fossil fuel industry. The IRA requires the federal government to offer an annual minimum area of specified public lands for oil and gas drilling. The act also required prioritisation of oil and gas auctions over renewable energy on federal lands and offshore developments. As a result, the Biden Administration approved several large oil and gas projects on public lands.

State-level action to end fossil fuel production

California is the only oil and gas producing state that plans to end oil and gas production. The state banned new fracking permits from 2024 and plans to phase out oil production by 2045. California is a founding associate member of the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance (BOGA), launched at COP26. Washington state joined BOGA at COP27 in 2022 and has implemented measures to ban new fossil infrastructure, including oil refineries (BOGA, 2021, 2022). The US is not a member of BOGA.

Transport

In 2022, the transport sector accounted for 28.5% of total US GHG emissions: the largest contributor to total US GHG emissions. Total sector emissions increased by 19.4% between 1990 and 2022, driven by increased motorised transport demand. Road transport is responsible for most of the sector’s emissions: light, medium, and heavy-duty trucks and passenger cars accounted for 79.8% of total sectoral emissions in 2022 (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2024c).

Progress towards reducing emissions from transport—especially from road transport—is projected to slow significantly under the Trump Administration. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has moved to repeal its GHG emissions for new vehicles, while the US Department of Transportation (DOT) has laid the groundwork to overturn its fuel economy standards for new vehicles.

The passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBB) will substantially slow the sale of electric vehicles (EVs). In combination, these executive and legislative actions will prolong the production and sale of emissions-intensive internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles and obstruct the US transition towards EVs, accelerated under the Biden Administration through the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) and the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

Before the OBBB’s enactment, the IRA was expected to reduce transport sector emissions by 15%–35% in 2035 relative to 2005 (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2023).

Transport decarbonisation targets

In January 2025, the Trump Administration eliminated the Biden Administration’s target for 50% of all new vehicles sold in 2030 to be battery electric vehicles (BEVs), plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs), and fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) (The White House, 2021a). It is important to note that the previous administration’s target is not aligned with limiting warming to 1.5°C. To be compatible with limiting warming to 1.5°C, the CAT finds that 95–100% of new light-duty vehicle sales in the US must be EVs by 2030 (Climate Action Tracker, 2020).

The Trump Administration has categorically abandoned the Biden Administration’s commitment to achieving net zero emissions across all sectors by 2050 (U.S. Department of Energy, 2025b). In doing so, the Trump Administration has discarded the Long-Term Strategy’s (LTS) emission reduction target for the transport sector, which sought to reduce the transport sector’s emissions by 80%-100% by 2050 below 2005 levels.

Electric vehicle incentives

The OBBB eliminates key federal purchase incentives for EVs, which will substantially decrease the light-duty EV sales and increase GHG emissions from road transport. The OBBB discontinues three tax credits for EVs that were expanded by the IRA: the New Clean Vehicle Credit, the Qualified Commercial Clean Vehicle Credit, and the Used Clean Vehicle Credit.

All three tax credits were set to expire in 2032 but will now be phased out by September 2025 (IRS, 2025b). The three credits, which are described in more detail in the CAT’s previous US assessment, have driven growth in EV sales, which tripled between 2021 and 2024. In 2024, EVs accounted for approximately 10% of all new light-duty vehicle sales. By phasing out the credits, the OBBB introduces significant instability into the US regulatory framework for EVs, jeopardising consumer demand for EVs and industry investment in EV production.

The termination of the IRA’s EV tax credits will effectively halve the share of EVs in the new light-duty vehicle sales in 2030. Following the OBBB’s passage, EVs are projected to make up approximately 20%-30% of new light-duty vehicles sales in 2030 (Energy Innovation, 2025; Jenkins et al., 2025). Prior to the OBBB’s passage, the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) forecast that battery electric vehicles (BEVs), plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs), and fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) would account for 50% of new light-duty vehicles sales by 2030; achieving the Biden Administration’s target for electric vehicle sales in 2030 (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2025a). Other research suggests that, if the IRA’s tax credits had remained in place, EVs could have made upwards of 60% of new light-duty vehicles sales in 2030(King et al., 2024a). The resulting impact on direct and indirect emissions is considered in the CAT’s current policy projections (see Assumptions section).

Beyond eliminating demand-side tax credits for EV sales, the OBBB also modifies supply-side tax credits for EV component manufacturing. The Advanced Manufacturing Production Tax Credit, expanded by the IRA, spurred domestic production of clean energy components for energy and transport, including EV batteries. The OBBB does not eliminate the credit for battery production but introduces strict domestic manufacturing requirements. Such requirements could stimulate capital investment in US-based battery manufacturing. However, given that the OBBB eliminates the tax credits that are driving domestic demand for EVs, the introduction of stringent domestic production requirements will more likely decrease, rather than increase, battery manufacturing capacity additions in the US.

Before the OBBB was enacted, the Advanced Manufacturing Production Tax Credit, in combination with the Clean Vehicle Tax Credits’ domestic production requirements, mobilised over USD 100bn in capital investment in EV assembly and battery manufacturing plants in the US and created over 100,000 jobs (Jenkins, 2025; Turner, 2025). Domestic EV assembly capacity was projected to double by 2030, if the OBBB had not become law.

The OBBB phases out the Alternative Fuel Vehicle Refueling Property Credit, which will directly slow growth in the deployment of EV recharging points and indirectly slow growth in the deployment of EVs. The tax credit, which was set to expire in 2032, will be eliminated in June 2026. Since the IRA’s passage, the number of publicly accessible EV recharging points increased by approximately 85%: the US has over 230,000 publicly accessible EV recharging points as of August 2025 (Joint Office of Energy and Transportation, 2025; U.S. Department of Energy, 2025a).

The OBBB rescinds USD 4.7bn in federal funding for decarbonisation initiatives in the transport sector. Most notable is the recission of unobligated funding for the Low-Carbon Transportation Materials Program and the Clean Heavy-Duty Vehicles Program. The Clean Heavy-Duty Vehicles Program provided USD 1bn in grants to subnational governments to offset the costs of replacing heavy-duty vehicles with zero-emissions alternatives and installing related recharging and refuelling infrastructure.

Emissions and efficiency standards

The Trump Administration is seeking to repeal standards for vehicle tailpipe emissions and fuel efficiency, which were strengthened under the Biden Administration.

Under the direction of the Trump Administration, the EPA, in July 2025, proposed to revoke all GHG regulations for light, medium, and heavy-duty vehicles and engines by rescinding the 2009 Endangerment Finding, which serves as the EPA’s legal basis for regulating greenhouse gas emissions from stationary and mobile sources (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2025e).

Independent of the EPA’s proposed rescission of the Endangerment Finding, the EPA, in March 2025, announced a separate reconsideration of the Multi-Pollutant Emissions Standards for passenger cars, light-duty trucks, and medium-duty vehicles. The standards were made more stringent under the Biden Administration in early 2024 and were planned to phase in from 2027 through 2032, and set progressively stricter fleet-wide CO2 emissions targets for auto manufacturers. If the standards were to remain in effect, auto manufacturers would have to produce between 30-56% battery electric vehicles in 2032 to meet the average emissions target (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2024b).

In June 2025, the US Department of Transportation’s (DOT) National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) issued an interpretive rule to reset the light-duty vehicle Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2025b). The CAFE standards, which establish fleet-wide fuel economy targets for auto manufacturers, function as a key regulatory driver for improving vehicle efficiency, lowering consumer costs, and reducing GHG emissions.

In the interpretive rule, the NHTSA does not alter existing fuel economy standards but reframes its authority and methodology for setting future standards. Most notable is that the NHTSA will no longer consider electric vehicles and their contribution to improving fleet-wide fuel economy in future standards. As a result, the interpretive rule enables the NHTSA to reissue lower, less stringent fuel economy standards. The NHTSA’s rule also similarly reconsiders the medium and heavy-duty fuel efficiency (MDHD) standards. Under the Biden Administration, the NHTSA raised the CAFE and MDHD standards’ ambition. In combination, the standards would have reduced emissions by over 710 MTCO2 by 2050.

Irrespective of the NHSTA’s future CAFE standards, the OBBB compromises the existing CAFE standards’ implementation by removing non-compliance penalties for auto manufactures. By removing penalties, carmakers are no longer fined for producing light-duty vehicles that do not meet the CAFE standards. The penalties previously incentivised auto manufactures to produce more fuel-efficient vehicles, which simultaneously reduce GHG emissions and consumer costs. Between model years 2010 and 2020, the NHSTA collected over USD 1bn in non-compliance fines (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2025a)

State-level transport decarbonisation efforts

The OBBB’s elimination of federal incentives for EVs is partially offset by state-level purchase and tax incentive schemes. In 2024, more than half of all US states provided additional incentives for light-duty EV purchases. State governments also provide additional incentives for heavy-duty EVs.

State-level vehicle emissions standards and EV sales targets can further counteract regulatory changes at the federal level. However, the federal government is seeking to limit states’ abilities to regulate vehicle emissions and scale EV uptake.

In May 2025, the Senate revoked California’s ability to enforce its Advanced Clean Cars II (ACC II) regulation, which progressively strengthens vehicle emissions standards and ultimately phases out light-duty ICE vehicles in 2035 (Rotondi et al., 2025). The Senate’s disapproval of the ACC II regulation does not only impact California: 12 other states duplicated and adopted the ACC II regulation, resulting in over one-third of all LDV sales in the US being subject to the 2035 ICE vehicle phase out target (IEA, 2024; California Air Resources Board, 2025). The Senate’s revocation means that California, as well as the other 12 states that have adopted the ACC II regulation, cannot enforce the phase-out of ICE vehicles.

The US did not sign the 100% EVs declaration at COP26. Signatories agreed that by 2040, 100% of new car and van sales should be electric vehicles (Race to Zero, 2021). Despite the absence of the federal government’s signature, many US subnational and non-state actors, including states, cities, and automakers, signed the declaration (UK COP 26 Presidency, 2021).

Aviation decarbonisation

Emissions from commercial aviation in the US are projected to double by 2050 without ambitious policy action and technological improvement. Sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs) can support the decarbonisation of aviation in the short term. The IRA introduced two tax credits—the Clean Fuel Production Credit and the Sustainable Aviation Fuel Tax Credit—to encourage the production and adoption of sustainable fuel technologies in the aviation industry.

The Clean Fuel Production Credit encourages the production of clean transport fuels, including SAFs. The OBBB makes several amendments to the Clean Fuel Production Credit (Cockerham et al., 2025). Positively, the OBBB extends the credit from 2027 until 2029. However, the act also reduces the tax credit value, introduces new domestic production requirements, and excludes indirect land use change emissions when calculating fuel lifecycle emissions. The exclusion of indirect land use change emissions—a critical measure for understanding the unintended emissions impact of biofuel production—significantly undermines the credibility of the lifecycle emissions analysis.

The Sustainable Aviation Fuel Tax Credit, which phased out at end of 2024, incentivised the sale and use of sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs) that reduced lifecycle GHG emissions by at least 50% compared to petroleum-based jet fuel (U.S. Department of Energy, 2022).

Industry

Direct GHG emissions from industry accounted for 23% of total US emissions in 2022, making it the third largest contributor to US GHG emissions after the transport and power sectors.

Industrial emissions have remained largely stable over the past decade, even as the US economy transitioned from a manufacturing to a service-based economy and as industrial processes have become more energy efficient and shifted to less emissions-intensive fuels.

Under the Biden Administration, the US implemented a diverse patchwork of financial incentives to research and develop critical technologies for industrial decarbonisation. However, the Biden Administration did not introduced instruments to facilitate the commercialisation of many of the technologies needed in hard-to-abate industrial subsectors.

The 2025 One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBB) modifies federal incentives—many of which were established by the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)—to encourage energy- and emissions-intensive industry in the US and abroad. We incorporate the OBBB’s effects on non-CO2 emissions into our current policy projections (see Assumptions section).

Carbon capture incentives

The OBBB revises the main federal subsidy for carbon capture technologies to incentivise the utilisation of captured CO2 for fossil fuel extraction. The OBBB alters the Tax Credit for Carbon Sequestration so that CO2 storage and utilisation, including for enhanced oil recovery (EOR) and natural gas recovery, receive the same tax credit. Before the OBBB, geologically storing captured carbon received a larger tax credit than commercially utilising captured carbon. By providing the same tax credit for CO2 storage and CO2 utilisation, the OBBB encourages fossil fuel extraction.

It is important to note that carbon capture technologies, despite decades of large subsides for research, development, and implementation, have yet to demonstrate commercial viability or operational scalability. Continued federal support for unproven carbon capture technologies coincides with sustained lobbying efforts by fossil fuel interest groups, which spent nearly USD 1bn on lobbying legislative and executive government officials on carbon capture policy between 2005 and 2024 (Gulden and Harvey, 2025).

Steelmaking coal incentives

The OBBB incentivises the emissions-intensive extraction of metallurgical coal, a type of coal used for steel production. The US Department of Energy (DOE) reclassified metallurgical coal as a “critical mineral” in May 2025, which enabled the OBBB to extend coverage of the IRA’s Advanced Manufacturing Production Credit to subsidise metallurgical coal’s production. The credit, worth 2.5% of production costs, applies to metallurgical coal production, regardless of whether the production occurs in the US or not.

Through the tax credit, the US coal industry is expected to receive an annual tax benefit of USD 200m-300m. Even before the OBBB’s passage, the US coal industry was increasingly shifting its focus towards metallurgical coal because of growing export demand (Hedgepeth and Lavelle, 2025). Approximately 75% of all metallurgical coal produced in the US is exported to foreign markets, where it is used in emissions-intensive steel production (Buffie et al., 2025).

Hydrogen production incentives

Hydrogen played a central role in the Biden Administration’s strategy for decarbonising hard-to-abate industrial processes and replacing fossil fuel-based feedstock with cleaner alternatives. The IRA established the Hydrogen Production Tax Credit to incentivise domestic production of clean hydrogen (The White House, 2023). The OBBB maintains the Hydrogen Production Tax Credit but makes the credit less accessible.

Fluorinated gas regulations

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is reconsidering a key rule—the Technology Transitions Rule—that underpins the American Innovation and Manufacturing (AIM) Act, which seeks to phase down the production and imports of hydrofluorocarbon emissions (HFCs) by 85% by 2036. The AIM Act was enacted under the first Trump Administration in 2020. Nevertheless, the second Trump Administration instructed the EPA to reconsider the rule as a part of its broader deregulatory agenda. The AIM Act, if retained, is expected to reduce emissions by 4.7 GtCO2e by 2050 (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2021). In 2024, the US reduced HFC emissions by 40% below 2020 levels (Haroldsen, 2024).

Buildings

In 2022, direct GHG emissions from buildings accounted for 13.5% of total US GHG emissions; 7.3% came from commercial buildings and 6.2% from residential buildings. When accounting for indirect, electricity-related emissions, the buildings sector made up nearly one-third of US total GHG emissions in 2022. To be 1.5°C compatible, the CAT estimates that emissions from buildings in the US should be 60% lower in residential buildings and 70% lower in commercial buildings by 2030 compared to 2015 (Climate Action Tracker, 2021, 2025).

The Trump Administration is sidelining energy conservation and emissions reductions in the buildings sector. The administration has revoked federal support for retrofits, heat pumps, building codes, and energy performance standards, which will have significant repercussions for sectoral emissions. Unlike in other sectors, key mitigation technologies and measures have high upfront costs or are not yet cost-competitive. Other challenges for reducing emissions from the sector include the long lifetimes of buildings and their technologies, as well as highly diverse, context- and climate-specific needs for buildings.

Decarbonising heating

Several policy instruments, at both the federal and state level, incentivise the transition to low-carbon heating technologies. Heat pumps have emerged as the key technology for decarbonising the buildings sector, which also offer public health benefits and protect households from volatile fossil fuel prices. The market share of heat pumps in residential cooling equipment has risen from 34% to 44% over the last decade, but traditional air conditioning units still dominate the market (RMI, 2025)Fossil fuels remain the most common heating source in the buildings sector: fossil gas, propane, and oil are used by nearly 60% of households. Electricity, including both older electric resistance heaters and modern heat pumps, is used to heat 40% of homes (Muyskens et al., 2025)

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBB) eliminates a key federal incentive for heat pumps. The OBBB phases out the Energy Efficient Home Improvement Credit at the end of 2025, which offered homeowners a tax credit of up to USD 2,000 annually for the installation of heat pumps, as well as biomass stoves and boilers (IRS, 2025a).

Low and middle-income households are eligible for point-of-sale rebates under the High-Efficiency Electric Homes Rebate Act (HEEHRA), which offers up to USD 8,000 for heat pumps and USD 14,000 for full electrification project. As of August 2025, the programme had not been eliminated, and funds appear available until 2031 (Schubel, 2025).

Several states and municipalities offer their own tax credits and rebates and have made low-interest loans available for electrification projects. Washington's building codes, for example, mandate the installation of heat pumps for space and water heating in new residential and commercial buildings. Colorado is implementing the US's first Clean Heat Standard, which requires heating fuel providers to gradually increase the amount of clean heat provided (BDC, 2024)

Energy efficiency improvements

Before the Trump Administration, two primary policy instruments supported energy efficiency improvements in buildings: financial incentives and building codes. The 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) and the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) allocated substantial funding through tax credits and rebate programmes to promote home energy efficiency. However, many of these initiatives have been scaled back or eliminated under the Trump Administration.

The OBBB phases out the Energy Efficient Home Improvement Credit by the end of 2025. The credit offered homeowners an annual tax credit of up to USD 1,200 for improvements, including insulation and window replacements (Stanek, 2025). The OBBB also rescinds much of the federal funding that was allocated under the IRA’s rebate programmes; notably, the Home Efficiency Rebates (HOMES) program and the HEEHRA program. In doing so, the OBBB undermines the ability of states to implement these rebate schemes effectively.

Building codes are a key driver of energy efficiency improvement in new construction and renovations. Building codes are primarily developed and enforced at state and local levels, while the federal government contributes financial and technical support. Under the Trump Administration, there has been a significant reduction in federal leadership and support.

The BIL allocated USD 225m to support state and local implementation of energy codes; facilitating code adoption, enforcement, training, and technical assistance. Complementing this, the Biden Administration's National Initiative to Advance Building Codes unlocked USD 1 billion in IRA grants to help subnational governments adopt modern building and energy efficiency standards, with support from multiple federal agencies. One of these agencies, FEMA, has since been directed to halt its effort to promote stronger disaster-resilient codes by the Trump Administration, while the OBBB rescinded significant grant funding originally allocated to these programmes (Sommer, 2025).

Building codes typically only apply to new construction or are triggered by major structural changes during renovation projects. As a result, the majority of existing buildings remain unaffected by energy or building codes, since no regulatory instruments mandate minimum energy efficiency standards or require renovations. Moreover, there is no overarching framework that outlines a clear roadmap with concrete measures for achieving an energy-efficient building stock.

Improving the energy efficiency of products and appliances

The US Department of Energy (DOE) sets out mandatory minimum energy performance requirements for a wide range of products under the Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA). Products that do not meet these standards cannot be sold in the US. According to a 2023 review, standards for consumer products and appliances in the US are generally ambitious: most meet or exceed international best practice (Mavandad and Malinowski, 2023).

However, while more stringent standards for refrigerators and freezers, air conditioners, clothes washers and dryers were finalised by the DOE in 2023 and 2024—expected to reduce emissions by an average of 20 MtCO2e per year (U.S. Department of Energy, 2023a, 2023b, 2024b)—the agency has since announced it will withdraw several products from the EPCA’s covered products list. Furthermore, energy conservation or efficiency standards, as well as test procedures, for several products have been revoked.

In May 2025, the Trump Administration began dissolving the EPA’s Office of Atmospheric Protection, which will eliminate the ENERGY STAR program. The ENERGY STAR programme is a voluntary labelling initiative designed to identify and promote products that meet high energy efficiency standards set by the EPA. The programme has saved over 5 trillion kWh of electricity and 4bn MTCO2e since 1992 (ENERGY STAR, 2023).

Embodied carbon

The construction of buildings contributes significantly to embodied life-cycle carbon emissions. Recent estimates suggest that the building construction industry is responsible for 6% of total U.S. GHG emissions (Huynh et al., 2023).

There are several policy measures that can address embodied carbon emissions. Under the IRA, USD 100m was allocated to support the development of standardised labels for low-embodied carbon building materials. With the OBBB, and before implementation had begun, the labelling funds were permanently removed (IRA Tracker, 2025). The Buy Clean Initiative of 2022 further aimed to reduce emissions associated with materials like steel, concrete, and glass by promoting the use of low-carbon alternatives in federal procurement (Chase, 2024). After the Trump Administration abandoned the federal Buy Clean strategy, multiple states have stepped in to continue the effort, aligning the initiative with their own sustainable procurement policies (U.S. Climate Alliance, 2025).

Commercial and public services buildings

Under the Trump Administration, many programmes offering financial incentives to improve the energy efficiency of commercial and public buildings have been terminated. In May 2025, the DOE began reconsidering its emissions standards for federal buildings(Columbia University, 2025). The standards, which were revised under the Biden Administration, mandated federal buildings to reduce on-site fossil fuel use in new construction and major renovations by 90% between 2025 and 2029 (U.S. Department of Energy, 2024a).

These setbacks in both financial support and regulation are significant, as the federal government is the largest energy consumer in the US, and federal buildings represent a notable share of its emissions (Council on Environmental Quality, 2024).

Agriculture

Greenhouse gas emissions from the agriculture sector made up 9% of US emissions in 2022. Between 1990 and 2022, agriculture emissions increased by 8%, driven by the growth of the livestock sector and the intensification of farming practices. Nitrous oxide emissions from soils accounted for half of the sector’s emissions. Enteric fermentation and manure management from livestock are other significant sources.

The Trump Administration has reversed, restructured, and deprioritised climate change-related activities and funding streams in the agriculture sector (Liliston, 2025). Recently established initiatives, such as the USD 3bn Partnerships for Climate-Smart Commodities programme, were cancelled, while portions of the Inflation Reduction Act’s (IRA) conservation funding have been revoked or redirected (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2025).

The IRA had initially earmarked USD 19.5bn for mitigation activities in the agriculture sector, mainly by directing funds towards existing conservation programmes, such as the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) and the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) to offer financial and technical support to farmers to reduce emissions (Monke et al., 2022).

The OBBB increases baseline funding for EQIP and CSP (National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition, 2025). However, the act also weakens environmental requirements under EQIP and CSP and rescinds the IRA’s targeted mitigation and adaptation funding. Historically, the programmes’ funding was difficult to access due to high demand and limited institutional capacity (Happ, 2023; Tham, 2023). While the increased funding may reach more farmers, it primarily benefits large, monoculture producers.

Only one-fifth of total EQIP spending went towards the implementation of agricultural practices that directly reduce GHG emissions in 2019 and 2020 (Schechinger, 2022). A significant portion of funding also goes towards manure management practices, including biodigesters that convert manure into biogas, which can be sold for profit and, therefore, may incentivise farmers to maintain or increase their herd sizes (Happ, 2024; Schechinger, 2024).

The Farm Bill remains a major area of contention because it is a policy that heavily influences farmers’ decisions on what food to produce and how to produce it. The 2018 bill was extended through FY2024, but the 2025 Farm Bill is still stalled in Congress over debates on its renewal. However, the OBBB’s passage has effectively reauthorised key Farm Bill measures and bypassed the traditional political channels by embedding major provisions under broader budgetary measures (Faber and Hayes, 2025).

The Trump Administration has also moved to disincentivise renewable energy development on farmland. The administration reduced federal support for solar uptake and revised the Rural Energy for America Program (REAP) to instead favour core farm operations.

The US lacks regulations on emissions from animal production or incentives to reduce herd sizes (Center for Biological Diversity, 2020). Instead, concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), which are detrimental to animal and environmental welfare, continue to be subsidised by the government (Happ, 2024). The US has one of the highest rates of meat and dairy consumption in the world. Historically, the meat industry has lobbied against key demand-side policies, such as changes to dietary guidelines, which constitute the basis of federal nutrition programmes and policy (Evich, 2016; Sebastian, 2024).

The US has a very high volume of food waste. Approximately one-third of available food is lost or wasted, and it may account for up to 6% of the country’s total GHG emissions when considering embodied emissions (Harwood et al., 2023). While the EPA set a goal to halve food loss and waste by 2030, the US is not on track to meet this target due to insufficient federal and state-level policies (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2024e). There is also little focus on food losses, which occur during the production and processing stages, due to a lack of data. Increased immigration enforcement under the Trump Administration has heavily impacted the US agricultural labour force and has led to widespread crop loss and food waste (Rahman and Gooding, 2025). Future action on food waste under the Trump Administration is unlikely.

Forestry

In 2022, the net CO2 removals from the land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF) sector corresponded to roughly 15% of total US GHG emissions. Between 1990 and 2022, the net carbon removal in the sector decreased by 13% due to the declining rate of net carbon accumulation in forests and on cropland, as well as an increase in emissions from urbanisation. The declining sink is attributed to aging forests and increasing CO2 and non-CO2 emissions from fires (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2024c).

The Trump Administration has shifted federal policy from carbon sink conservation and preservation to “active management” of carbon sinks which involves the rapid expansion of timber production under the pretext of wildfire suppression (The White House, 2025b). The administration announced its intention to revoke the 2001 Roadless Rule, which protects over 23 Mha of undeveloped national forests from most logging, large-scale mining, and road building activities (Hay, 2025).

In parallel, the OBBB puts the US forest carbon stock further at risk by mandating a 25% increase in logging on federal lands and locking in long-term timber contracts (Carbon180, 2025). The IRA initially provided support programmes, including further investments in the National Forest Service and Forest Legacy Program (The White House, 2023). However, the OBBB rescinded all unobligated funding from the IRA and other climate-specific forestry programmes, redirecting resources to generic conservation programmes.

The OBBB has additionally cut staffing and federal oversight measures for new forest projects such as environmental reviews and public consultation procedures, making it easier to expand logging while undermining transparency and safeguards (Carbon180, 2025). Furthermore, it encourages tree burning and using forest feedstocks for “sustainable aviation fuel” by subsidising new biomass and biofuel facilities (Smith, 2025).

While the Biden Administration reinstated the protections on Alaska’s Tongass National Forest following Trump’s reversal of a long-standing rule that severely restricted logging on the forest’s 16 million acres (Friedman, 2023). The intent to revoke Roadless Rule protections would reopen large portions of the forest for logging and roadbuilding, framed as supporting local economic development (Earthjustice, 2025). Considering that the Tongass makes up over one-fifth of the nation’s forest carbon stocks, its protection is critical to preserving the considerable US carbon sink (Dellasala et al., 2022).

Even without considering Trump’s rollbacks of forest protections, research from the US Forest Service raises concerns about the potential of US forests to store carbon in the long term, with land conversion, increased timber demand, climate change-related natural disturbances reducing the carbon absorption capacity of aging forests. Under a high wood demand scenario, US forests could even become a carbon source by 2070 (U.S. Forest Service, 2023).

Waste

The waste sector only made up approximately 2.5% of national emissions in 2022 but contributed to 17% of anthropogenic methane emissions (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2024c). Therefore, reducing methane emissions from landfills is key for reducing overall methane emissions.

Under the Biden Administration, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) finalised emissions standards to ensure that large municipal landfills significantly reduce their methane emissions (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2025d). The agency also developed the Landfill Methane Outreach Program to support methane collection and distribution at smaller, unregulated landfills (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2025c). Both the standards and program remain in place under the Trump Administration.

Methane

Methane is an important source of GHG emissions in the US, representing 15% of total GHG emissions in 2022, which are split between the oil and gas industry (37%), agriculture (36%), waste (19%), and land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF) (8%) sectors (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2024e).

The Trump Administration is backtracking on the Biden Administration’s progress towards reducing methane emissions. In March 2025, the Trump Administration annulled the US Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Methane Emissions Reduction Program, which sought to reduce methane emissions by charging a fee for methane emissions from oil and gas projects (Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, 2025). The EPA’s program was established by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). The IRA also provided 1.5bn in financial and technical assistance to monitor and reduce emissions from petroleum and natural gas facilities (The White House, 2023).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter