Targets

Target overview

In its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), the US has set a target to reduce emissions by 50%–52% below 2005 levels by 2030 (U.S. Government, 2021). This target covers all sectors and all greenhouse gases (GHGs). The CAT assessment excludes emissions from land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF) from this target, resulting in a 45%–50% reduction below 2005 levels by 2030. The CAT rates the US domestic target as “Almost sufficient” when compared to the reductions needed within its borders and as “Insufficient” when compared to its fair share contribution.

The US submitted a long-term strategy (LTS) to the UNFCCC in November 2021, officially committing to net zero emissions by 2050 at the latest (U.S. Department of State, 2021).

| USA — Main climate targets |

|---|

| 2030 NDC target | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Formulation of target in NDC | 50–52% below 2005 levels by 2030 (incl. LULUCF) | ||

|

Absolute emissions level in 2030 excl. LULUCF |

3,790–4,131 MtCO2e [37%–43% below 1990 by 2030] [42%–47% below 2010 by 2030] |

||

| Status | Submitted on 22 April 2021 | ||

| Net zero & other long-term targets | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Formulation of target | Net-Zero Greenhouse Gas Emissions by 2050 | ||

| Absolute emissions level in 2050 excl. LULUCF |

558–1,540 MtCO2e [77%–92% below 1990 by 2030] [78%–92% below 2010 by 2030] |

||

| Status | Submitted on 1 November 2021 | ||

NDC Updates

The US submitted its current, more ambitious NDC target on 22 April 2021. President Biden moved to re-join the Paris Agreement on his first day in office in 2021. In line with its re-joining the agreement, the US submitted a strengthened NDC, in which the government commits to reducing emissions by 50%–52% below 2005 levels by 2030 (including emissions from land use, land use change and forestry, or LULUCF).

The CAT estimates that the target would translate to a range of 3,790–4,131 MtCO2e absolute GHG emissions in 2030, excluding LULUCF (or 45%–50% below 2005 levels), depending on whether the sink from LULUCF is at the high or low end of the projections (U.S. Department of State, 2022).

The current NDC target represents major progress beyond the Obama-era target of 26%–28% below 2005 levels by 2025. Nevertheless, the NDC is not ambitious enough to bring US domestic emissions in line with what would be needed to achieve the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C limit.

CAT analysis indicates that the US should aim to reduce its national emissions by at least 58% below 2005 levels by 2030 (incl. LULUCF) and provide support to other countries in order to be consistent with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C limit. Doing so will also put the US on track to achieve the Biden Administration’s 2050 net zero target (Climate Action Tracker, 2021b). The US has not submitted an update to its NDC since 2021, even though the Glasgow Climate Pact mandates countries revisit and strengthen their NDCs.

| USA — History of NDC updates | 2016 NDC | 2021 NDC Update |

|---|---|---|

| 1.5°C compatible |

|

|

| Stronger target | N/A |

|

| Fixed/absolute target |

|

|

| USA | First NDC | 2021 NDC Update |

|---|---|---|

| Formulation of target in NDC | 26–28% below 2005 levels by 2025 (incl. LULUCF) | 50–52% below 2005 levels by 2030 (incl. LULUCF) |

|

Absolute emissions level excl. LULUCF |

5,450–5,689 MtCO2e in 2025 | 3,790–4,131 MtCO2e in 2030 |

|

Emissions compared to 1990 and 2010 excl. LULUCF |

14%–17% below 1990 by 2025 20%–23% below 2010 by 2025 |

37%–43% below 1990 by 2030 42%–47% below 2010 by 2030 |

| CAT rating | Critically insufficient* |

Domestic target: Almost sufficient Fair share target: Insufficient |

| Sector coverage | Economy-wide | Economy-wide |

| Separate target for LULUCF | No | No |

| Gas coverage | All greenhouse gases | All greenhouse gases |

| Target type | Absolute emissions reduction below a base year | Absolute emissions reduction below a base year |

* The ‘Critically insufficient’ rating was based on the fact that the US had withdrawn from the Paris Agreement and was not an assessment of the NDC emissions level, which itself would fall in the ‘Insufficient range’ based on the CAT’s prior rating system (which was updated in September 2021).

Target development timeline & previous CAT analysis

CAT rating of targets

The CAT rates NDC targets against what a country should be doing within its own borders as well as what would qualify as a country’s fair contribution to achieving the Paris Agreement’s long-term temperature goal. For assessing targets against the fair share, we consider both a country’s domestic emissions reductions and any emissions reductions it supports abroad through the use of market mechanisms or other ways of support, as relevant.

The US does not intend to use market mechanisms and will achieve its NDC target through domestic action alone. We rate its NDC target against both domestic and fairness metrics.

We rate the target of reducing emissions by 50%–52% (or 45%–50% excluding emissions from land-use, land-use change and forestry or LULUFC) below 2005 levels by 2030 as “Almost sufficient” when compared to modelled domestic emissions pathways.

The “Almost sufficient” rating indicates that the US target in 2030 is not yet consistent with the 1.5°C temperature limit but could be, with moderate improvements. If all countries were to follow the US approach, warming could be held at—but not well below—2°C. Although the target represents a significant improvement compared to its first NDC, the current target is not stringent enough to limit warming to 1.5°C and needs further improvements.

We rate the target of reducing emissions by 50%–52% (or 45%–50% excl. LULUCF) below 2005 levels by 2030 as “Insufficient” when compared with its fair-share emissions allocation.

The “Insufficient” rating indicates that US’ NDC target for 2030 needs substantial improvement to be consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C. The US target is at the least stringent end of what would be a fair share of global effort. The target is not consistent with the 1.5°C limit, unless other countries make much deeper reductions and comparably greater effort. If all countries were to follow US’ approach, warming would reach over 2°C and up to 3°C.

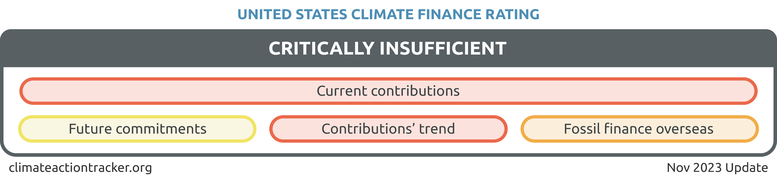

The US’ international climate finance contributions is rated “Critically insufficient” (see below) and is not enough to improve the US’ fair share rating.

We rate the US’ international public climate finance contributions as “Critically insufficient.” The US has committed to increase its climate finance, but contributions to date have been much lower than its fair share. To improve its rating, the US needs to ramp up the level of its international climate finance contributions and accelerate the phase-out of all fossil fuel financing abroad (and not only coal).

Contribution levels and trends

The US Congress approved a budget allocation for international climate finance of no less than USD 0.9bn (Congressional Research Service, 2024) for FY2024, although the Biden Administration requested an allocation of USD 5bn. As a result of a more stringent federal spending cap, the FY2024 finance provision is less than the provision in the first years of the Biden Administration (Thwaites, 2024). For FY2025, the administration accordingly reduced its requested funding to USD 3.5bn.

The US State Department, however, claims it is on track to reach its pledge to contribute USD 11.4bn per year by 2024, with a projected contribution of USD 9.5bn in FY2023 (U.S. Department of State, 2024). This discrepancy between the climate finance commitment approved Congress and that claimed by the US State department is due to the fact that Congress’ funding only represents a small share of US’ total international climate finance, as other agencies contribute the bulk of financing (Thwaites, 2024; U.S. Department of State, 2024). However, the sources of the US’ climate finance are not transparently reported.

While Congress’ budget allocation does not include any funding for the Green Climate Fund (GCF), the US government has pledged to contribute USD 3bn to the GCF. The GCF is the primary international vehicle for supporting developing countries in their efforts to respond to and build resilience to the climate crisis (DeLauro, 2022).

The commitment of USD 11.4bn per year by 2024 falls short of the US’ fair contribution. While the OECD reported in 2022 that international climate finance provided by developed countries exceeded the USD 100bn goal per year for the first time, a “new collective quantified goal on climate finance” post-2025 is already being discussed by UNFCCC parties (UNFCCC, 2024).

To demonstrate global leadership on climate finance and to contribute towards its fair share, the US needs to substantially scale up its international climate finance provisions in future. The CAT finance rating would improve if the US were to successfully augment its level of finance through a sustained upwards trend in annual contributions.

The US has historically provided a significant portion of its climate-related financial contributions as grants, which are more concessional than loans. Climate finance contributions declined during the Trump Administration, but this trend has since been reversed by the Biden Administration, which in 2021 increased its bilateral climate-related Official Development Assistance (ODA) (OECD, 2022).

Bilateral climate finance by the US, as reported as principal and significant financing, further increased in 2022 as a result of an increase in adaptation financing. Principal mitigation financing actually decreased by half, from almost USD 1bn to less than USD 500m, reflecting a shift by the Biden Administration towards adaptation financing (OECD, 2024). Overall, the US' allocation of funding to bilateral climate-related ODA increased from 3% in 2021 to 10% in 2022 of total ODA spending, but remains well below the OECD's Development Assistance Committee (DAC) member countries' average of 24% (Donor Tracker, 2021, 2023). This continues to highlight a substantial shortage in the US' financial commitment to addressing climate change through ODA. Increasing these contributions would not only allow the US to play a larger role in global climate action, but would also align with its renewed commitment to international cooperation under the Biden Administration.

Fossil fuel financing abroad

The US, along with several other countries, agreed to “end new direct public support for the international unabated fossil fuel energy sector” by the end of 2022 (The White House, 2021b). The 2023 G7 Communique claims to have achieved this goal (The White House, 2023d). However, the US has neither developed plans nor introduced policies to implement these commitments. The US also has not supported a proposal put forward by the European Union to end fossil fuel finance from export banks, which stands in stark contrast to the US commitment mentioned above (E&E News by POLITICO, 2024).

In 2023, the Export-Import Bank of the US (EXIM), an independent US government agency that provides concessions for projects that seek to boost US exports, continued to lend money to foreign fossil fuel projects, including USD 100m to Indonesia’s national oil company to expand an oil refinery and boost production. Estimates suggest that EXIM’s total lending amounted to USD 1bn in 2023 (Aronoff, 2023).

While the US government claims to be actively working with EXIM to end its financing of fossil fuel projects, the export agency itself does not seem to take a proactive role in doing so, claiming it has no jurisdiction to end these projects (Friends of the Earth US, 2024). In January 2024, EXIM’s lack of action resulted in two members of the agency’s climate advisory board resigning over a decision on a fossil fuel project in Bahrain (Friedman & Tabuchi, 2024). EXIM plans to finance further fossil fuel projects abroad, including in Guyana, Malaysia, Mexico, Mozambique, and Papua New Guinea (Friends of the Earth US, 2024).

Although the US has not approved any new domestic coal projects in more than a decade (Friedman & Tabuchi, 2024), the US continues to support existing coal projects abroad, such as the Jawa 9-10 Suralaya Coal Plant in Indonesia and the Long Phu 1 Coal Plant in Vietnam (EndCoal, 2020). The US should stop supporting all fossil fuel developments abroad to improve its climate finance rating.

Net zero target

The Biden Administration submitted an updated long-term strategy (LTS) to the UNFCCC in November 2021, in which the US officially commits to net zero emissions by 2050 at the latest. The net zero target covers all greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, makes transparent assumptions on CO2 removal by nature-based and technology-based solutions, and specifies several key components for comprehensive planning (U.S. Department of State, 2021).

The US government has several avenues to improve the scope, target architecture, and transparency of its net zero target. The US government could include international aviation and shipping in its target coverage, and explicitly commit to reach net zero emissions within its own borders without the use of international offsets.

The target itself could be enshrined in law in combination with adopting a legally binding review, revision, and reporting mechanism. The US government should further explain how its net zero target is a fair contribution to the global goal of limiting warming to 1.5˚C above pre-industrial levels, and transparently address any existing gap between its net zero target and what would be a fair target.

For the full analysis of the net zero target, click here.

2020 pledge

The effects of COVID-19 induced a temporary drop in emissions that helped the US meet its 2020 targets under the Copenhagen Accord. Total emissions in 2020 decreased by 22% below 2005 as a result of the pandemic-induced economic slowdown. The US 2020 target was to reduce emissions by 17% below 2005 levels by 2020 (U.S. Department of State, 2010). Despite reaching the 2020 target, GHG emissions bounced back to pre-pandemic levels in 2021.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter