Mid-year check on 2035 climate plans

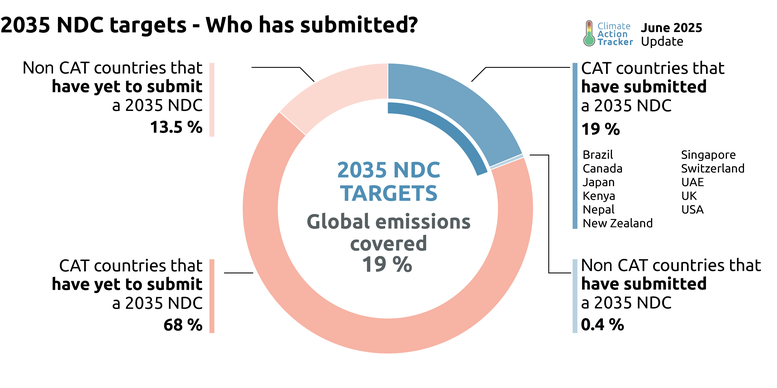

Only 11 CAT countries have submitted a 2035 target

Halfway through 2025 and, despite an early deadline this year, only 11 of the 40 countries the Climate Action Tracker (CAT) assesses have submitted a 2035 climate target (NDC). Of them, just one has put forward a domestic target that is 1.5˚C compatible if followed by increased international finance.

CAT countries account for around 85% of global emissions. Including 11 additional submissions made by non-CAT countries, 22 countries had submitted new targets by 19 June 2025, representing 19% of global emissions in 2022. The remaining CAT countries yet to submit their NDCs account for approximately 68% of global emissions.

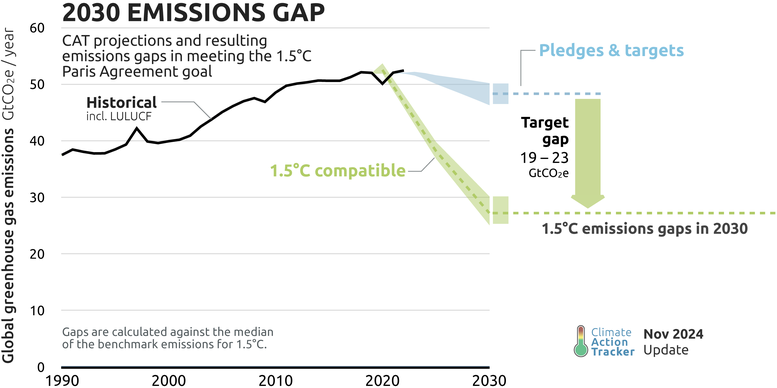

To keep the 1.5°C goal within reach, governments must strengthen their 2030 targets to help close the 19–23 GtCO2e gap[1] and halve global emissions by the end of the decade. They must also put forward robust 2035 targets that put the world on track to reach net zero greenhouse gas emissions in the second half of the century.

The 2035 NDCs submitted so far show a limited increase in ambition:

None of the countries we track have strengthened their 2030 targets in this latest round of submissions: an absolute necessity given the need to halve emissions by 2030 to keep the world on a pathway to avoiding dangerous climate change. A failure to substantially strengthen current 2030 targets and action would mean risking the ability to limit global warming to 1.5°C, likely leading to a multi-decadal, high overshoot of this limit, even if followed by strong 2035 targets.

- While many countries have proposed stronger targets for 2035 compared to 2030, the gap between those targets and a 1.5°C pathway has actually grown, signalling a weakening, not strengthening, of ambition.

- Though both Canada and Switzerland have set 2035 targets that are stronger than their 2030 targets, the gap between the new 2035 targets and the countries’ respective 1.5°C modelled domestic pathways have increased both in absolute and relative terms compared to their 2030 targets.

- Governments are relying on land sector sinks to enhance the ambition level of their national targets, rather than prioritising the urgently needed reductions in fossil fuel use for industry, transport, and other sectors. There is a pressing need for governments to report separately on the contribution of the land sector towards their targets, as growing scientific evidence shows that land sector sinks cannot substitute cutting fossil fuel emissions.

- Assessing Brazil's recently submitted 2035 NDC target was challenging, largely due to the lack of published government data on the expected contribution of the land use sector to the NDC target. We assumed a contribution from the land sector based on various data sources, which, in turn, leads to an unusually wide range of estimated emissions levels for all other sectors (excl. LULUCF) that are consistent with the NDC target.

- Canada does not include the emissions or removals from the land sector in the base year but allows accounting for land sinks in the target year in its 2035 NDC. This "gross-net" accounting leads to an unclear and difficult to quantify reduction target for the rest of the economy.

- An increasing number of countries are looking at relying on buying international offsets through the Paris Agreement's Article 6, to meet their targets. The Paris Agreement requires Article 6 to be used to increase ambition, not to weaken it.

- In the process of defining the EU’s 2035 and 2040 targets, some Member States are pushing for the introduction of international carbon credits under Article 6. The EU’s laws require the 2030 target and 2050 net zero target to be met without offsets. Reintroducing offsets into its plans would severely weaken the EU’s domestic ambition by opening the door to accounting loopholes and would put the achievement of the EU’s net zero target at risk.

- The lack of transparency on the share of emission reductions to be achieved domestically versus through international carbon credits makes it almost impossible to assess the stringency and ambition of Switzerland’s 2030 and 2035 targets.

Lack of progress is deeply concerning

The CAT global temperature projections for the end of the century have remained unchanged for the past three years, underlining the widening gap between science and action. This lack of progress is deeply concerning, especially as climate impacts are intensifying across every region of the world. We are seeing an alarming rise in catastrophic climate events, including record-breaking heatwaves, floods, and wildfires. The urgency to step up mitigation efforts and avoid weaking targets by relying on offsets and sinks has never been greater.

Current commitments and policies - the CAT “policies and actions” pathway - if unchanged, would see the world warming to 2.7˚C by 2100. They are not aligned with the level of action needed, increasing the risk that long-term global average temperatures will exceed 1.5°C, potentially in the early 2030s. The earlier the overshoot, the more difficult it is to come back from it.

Such an overshoot could lead to irreversible damage and long-term consequences for ecosystems and human societies alike. If governments don't turn around this pathway of current policies by 2030, we will exceed 1.5˚C at least for a few decades no matter what we do. But it is critical to continue to push for the highest possible ambition as every 0.1˚C matters.

There is still time to close the gap ahead of COP30 in Belém. While they have missed the February deadline, governments can - and must - do the following to increase the ambition of their climate action:

- Put forward stronger 2030 targets that close the 19–23 GtCO2e gap and halve global emissions by the end of the decade compared to 2019 levels.

- Present 2035 targets that align global emissions with a 1.5°C compatible trajectory.

- Transparently communicate climate finance contributions and needs.

- Clearly separate carbon sinks and other removals from emissions reduction efforts in other sectors, to ensure transparent targets and prevent creative accounting.

- Only use Article 6 to increase ambition, meaning it should represent additional emissions reductions, beyond 1.5°C aligned domestic action.

The opportunity to course-correct is still within reach. Renewable energy is growing exponentially, as is the uptake of EVs. Investments in clean energy are now double those for fossil fuels, particularly oil and gas, for the first time, while investment in clean manufacturing capacity is growing rapidly.

NDC series

To support governments in raising ambition ahead of COP30, the CAT has produced seven country-focused reports: six on major emitters that have not yet submitted updated NDCs (China, India, the European Union, Indonesia, South Africa, and Australia) and one on the COP30 host country, Brazil. Together, these 7 countries accounted for around 50% of global GHG emissions (including LULUCF) in 2022.

These reports aim to provide a clear picture of how each country can strengthen its climate action in upcoming NDCs, in line with limiting warming to 1.5°C. Although Brazil submitted its 2035 NDC last November, it falls short of a 1.5°C pathway and lacks clarity on the role of LULUCF. As COP30 host, Brazil has a unique opportunity to lead by example. We included it in our series to urge a more ambitious and transparent NDC: one with stronger 2030 and 2035 targets that truly aligns with a 1.5°C pathway, separate LULUCF goals, and a clear long-term strategy for achieving climate neutrality by 2050.

In-depth country analyses

Frameworks used

We present 1.5°C-compatible 2030 and 2035 targets for each country, assessed using the two key frameworks applied by the CAT: modelled domestic pathways and fair share. The modelled domestic pathways show what is technically and economically feasible for a country to achieve within its own borders, based on global least-cost mitigation. For some countries, this is only achievable with significant international climate finance. The fair share approach considers a wider range of equity principles - such as historical responsibility, capacity to act, and equality - to determine a country’s overall fair contribution to the global effort.

Comparing a country’s fair share range and modelled domestic pathways offers insights into which governments should provide climate finance and which should receive it. Developed countries with large responsibility for historical emissions and high per-capita emissions, must not only implement ambitious domestic climate action but must also support climate action in developing countries with lower historical responsibility, capability, and lower per-capita emissions.

By comparing both frameworks, we highlight not only the level of ambition required within each country but also the global dynamics of responsibility and support. To ensure consistency and comparability in tracking progress, targets in the country-focused reports are presented using each country’s own NDC reference year.

Brief assessments of the NDCs submitted so far (CAT countries only)

The CAT is assessing the new 2035 NDC targets and, for countries it tracks, provides an analysis of each target’s ambition and alignment with a 1.5°C compatible pathway.

Brazil: Brazil submitted a target to reduce emissions between 59–67% below 2005 levels by 2035. Assessing the ambition of this target has been difficult due to the lack of transparency on how much the land sector sink will contribute to the target, given the country's need for urgent reductions in the energy sector.

This results in an extraordinarily wide range of estimated emissions from all other sectors (excl. LULUCF) that are consistent with the NDC target. The lack of transparency is a clear issue for climate integrity – the public and the scientific community need to be able to understand what a government is proposing to do and in the present situation, Brazil’s NDC provides no clarity on this. We conclude that Brazil’s 2035 NDC target is not 1.5°C compatible.

Canada: Canada’s 2035 NDC sets a target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 45–50% below 2005 levels by 2035. However, this target is based on a ‘gross-net’ approach, where reductions from the land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF) sector are counted towards achievement, even though LULUCF is excluded from the baseline. This approach reduces the pressure to achieve real reductions in fossil fuel emissions and introduces uncertainty into the stringency of the target. Excluding LULUCF, the target translates to a 40–49% reduction below 2005 levels, which is not 1.5°C compatible, falling well short of the 65% cut required for a 1.5°C pathway. Canada’s 2035 target does not include sectoral targets, and the gap between its NDC targets and what is needed for 1.5°C is widening. The lack of an updated, ambitious 2030 target further undermines Canada’s climate credibility.

New Zealand: The new 2035 NDC is weak, and could even allow for higher emissions than under the 2030 mitigation target. It falls well short of being 1.5°C-aligned with our modelled domestic pathways.

New Zealand’s 2035 NDC target aims to reduce net emissions by 51–55% below 2005 gross levels but may even allow for higher gross emissions relative to the 2030 target and introduces greater uncertainty in its reduction pathway due to the wide range between the estimated minimum and maximum emission values. Shifting from a multi-year to a single-year target, combined with its reliance on unproven technology for emission reductions, increases the uncertainty of achieving its 2035 and the long-term target.

Switzerland: While Switzerland’s 2035 NDC target of reducing GHG emissions to at least 65% below 1990 levels appears to reflect an increase in ambition compared to its 2030 target, the new target not only remains insufficient, but it is also diverging from a 1.5° aligned pathway.

The gap between the new target and our cost-effective 1.5°C modelled domestic pathway has increased both in absolute and relative terms compared to the 2030 target. The lack of transparency on the share of emission reductions to be achieved domestically versus through international carbon credits makes it almost impossible to assess the stringency and ambition of this target.

UAE: While the UAE submitted a significantly more ambitious 2035 mitigation target compared to its 2030 target, we do not consider its overall NDC commitment as 1.5°C compatible. It has not updated its 2030 target, which implies an unrealistic acceleration of mitigation action - from a 7% reduction in 2030 to a 44% reduction in 2035, below 2019 levels. The UAE is not on track to meet its 2030 target with its current policies and without details on how emissions cuts will be achieved, the 2035 target is not credible.

The UK: About the only bright spot in the NDC landscape is the UK’s 2035 NDC, which is beginning to align its actions at home with a 1.5° pathway, which should provide an inspiration to other developed countries to take a big step forward. The UK would need to support its 2035 NDC target - of reducing emission by 81% below 1990 levels by 2035 - with more international climate finance to be a fully 1.5°C aligned contribution to the Paris Agreement. What matters most now is action to reduce emissions in the real economy.

The new government has inherited a vast implementation gap, with existing policies covering only 24% of the emissions reductions needed to meet the new 2035 target. Urgent action will be needed to introduce, strengthen and implement policy mechanisms that turn this new ambition into reality.

USA: The Trump Administration is walking away from climate science and action and favouring the expansion of oil and gas; attempting to unwind the policies introduced by former President Biden. This will be a major setback to climate action in the US and if the Trump Administration is successful in pushing its agenda globally, it could get a lot worse.

In December 2024, the Biden Administration submitted the US 2035 NDC to the UNFCCC, and while the Trump Administration is withdrawing from the Paris Agreement, the NDC can still be a guiding document for the roughly half of the US states who support continued climate action. With the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act at risk, these subnational actors must resist rollbacks and raise the ambition of their own climate policies to keep the 2035 target within reach.

Footnotes

[1] This is according to the latest CAT Warming Projections Global Update released in November 2024. This “target gap” is the difference between the emissions reductions countries have currently pledged, and the level of reductions needed to keep global warming below 1.5°C.

[2] Kenya and Japan have also submitted 2035 targets, which we will be analysing soon.

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter

Australia report

Australia report

Brazil report

Brazil report

China report

China report

EU report

EU report

India report

India report

Indonesia report

Indonesia report

South Africa report

South Africa report