Country summary

Overview

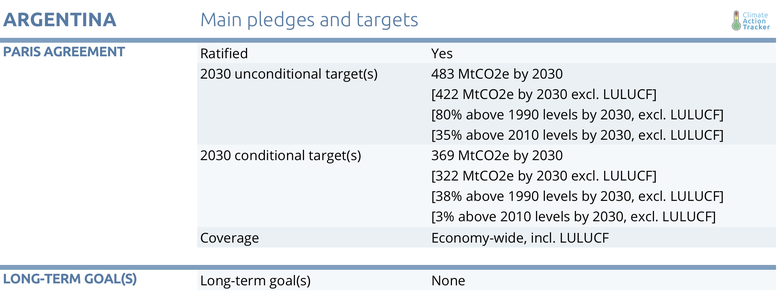

Argentina is one of the few countries that has updated its NDC targets since the adoption of the Paris Agreement. Even though it belongs to the present NDC cycle, this NDC update took place in 2016 and is not part of the recent series of updates between 2019‑2020. The CAT still rates Argentina’s NDC “Highly Insufficient”, indicating that the climate commitment is not consistent with holding warming to below 2°C, let alone limiting it to 1.5°C as required under the Paris Agreement (see “fair share” section).

On 27 October 2019, Alberto Fernández was elected President and replaced Mauricio Macri in office. To date it is uncertain how - or whether - this change will affect the country’s climate policy. During the last term of office of Ferndández’ new vice president, former president Cristina Kirchner (2007-2015), environmental issues, including climate change, had been very low on the political agenda.

President Fernández’ election platform included a very vague section on environment and sustainable development, and it remains unclear how this will translate into government policy. While it will be difficult to completely stop programmes and processes that have been initiated under his predecessor Macri, such as the RenovAr programme or the NDC revision and Long-Term Strategy (LTS) processes, progress may get delayed, depending on the extent to which there will be changes in the technical teams working on climate issues in the respective ministries and secretariats.

For full details see pledges and targets section.

Under the previous government of President Macri (2015-2017), Argentina has shown significant positive developments in the climate arena by adopting policies such as the ‘Biofuels Law’, the ‘Renewable Energy Law’ and a carbon tax on fossil fuels. The renewables support scheme RenovAr completed four auctioning rounds and a fifth round has been announced to be held at the end of 2019. In July 2019, Argentina declared a climate emergency and the Senate passed a draft Climate Change Law. Macri also announced the goal of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050. The development of these policies is rather uncertain given the change of government.

On the other hand, Marci’s presidency witnessed a push by parts of the government towards the exploitation of domestic fossil resources which has threatened progress in climate action (See our analysis of current policies): some sections of the government were strongly promoting exploiting national non‑conventional oil and gas reserves for domestic consumption and export, and seemed to prioritise this over expanding renewable electricity installations and improvements in electricity grids. It remains to be seen whether this pattern continues under President Fernández’.

It is clear that Argentina would have the capacity to reduced emissions significantly - in December 2017, the then Ministry of Energy released a set of energy scenarios, which project significantly lower emissions—if additional measures were implemented—compared to CAT’s current policy projections. With this ‘additional policies’ scenario, Argentina could even overachieve its unconditional climate target (NDC) submitted under the Paris Agreement.

Argentina is going through a severe economic crisis, which, under the former government, has led to changes in the structure of ministries with the objective of decreasing government spending. Included in these changes were departments dealing with climate change: the former energy ministry and the environment ministry both became secretariats, reporting to the Ministry of Economics and the president’s office, respectively. Similarly, the Ministry of Agriculture became a Secretariat of the Ministry of Production.

It is unclear whether there will be new structural changes under the new government, and which impact these will have on climate policy. The direct impact of decreased economic activity on emissions is also still unclear.

Whether Argentina will achieve its unconditional NDC depends mostly on the development of the energy sector. Uncertain variables are the speed of renewable energy expansion, additional nuclear plants, and demand projections. Under the most optimistic scenario, if Argentina were to implement additional policies to scale-up low carbon energy sources and reduce energy demand, it could even significantly overachieve its unconditional NDC target.

The scenarios from the former Ministry of Energy and Mining suggest an increase of renewable energy capacity of 14–18 GW by 2030, compared to only 4.7 GW that have to date been contracted under the renewable auctioning scheme RenovAr. The scenarios also assume further additions of nuclear capacity of almost 2 GW by 2030, although the scenarios show that investment costs for nuclear are about seven times higher than the costs of renewables and gas in Argentina. Also, solar PV is projected to be cost competitive with gas turbines before 2030.

Under more conservative assumptions, which only consider renewable and nuclear capacity additions currently underway, Argentina will miss its targets, unless it revises the energy split or implements actions in other sectors. Our policy projections, as well as the new scenarios from the Ministry of Energy and Mining, do not yet reflect the recently implemented carbon tax, and no studies yet exist that quantify the impact.

In January 2018, Argentina implemented a carbon tax covering most liquid fuels sold in Argentina, based on a price of 10 USD/tCO2e. In January 2019, the tax also became operational for fuel oil, mineral coal, and petroleum coke, at 10% of the full tax rate, with an annual increase of 10 percentage points until reaching 100% in 2028. The tax is estimated to cover 20% of the country’s GHG emissions. Natural gas is exempted from the tax, as is international aviation and shipping as well as the export of covered fuels.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter