Country summary

Overview

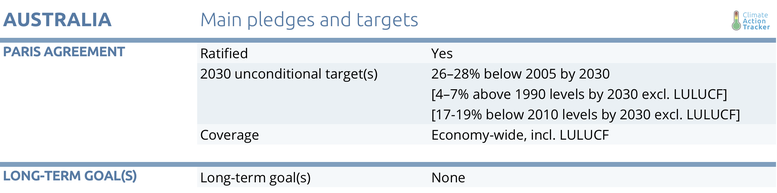

Australia’s Paris Agreement target is 26-28% reduction below 2005 levels by 2030 (including LULUCF). With current policies total emissions including LULUCF are projected to be about 7% below 2005 levels by 2030, rising from 15% below in 2013 the last full year before the present government repealed the carbon pricing system. After factoring out the highly uncertain LULUCF sector to focus on energy and industry emissions Australia’s Paris Agreement target translates to a 14-16% decrease from 2005 levels by 2030. Under current policies, Australian emissions are headed for an increase of 8% above 2005 levels by 2030 (excluding LULUCF), and if rated would be “highly insufficient”.

This means Australia’s emissions are set too far outpace its “Insufficient” 2030 target. Emissions excluding the LULUCF sector have increased by around 1% per year on average since 2014, the year in which Australia’s national carbon pricing scheme was repealed.In developments over the last year the Australian government dismissed the findings of the IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C , discontinued its funding to the Green Climate Fund (GCF), ignored the call by the UN Secretary General and its Pacific Island neighbours to increase its climate action, let alone the expressed desire of Australians for more action – and its emissions continue to increase, despite Government protestations to the contrary. Australia’s emissions from fossil fuels and industry continue to rise. The rapid ramp-up in the production of liquified natural gas (LNG) for export means LNG processing has driven huge increases in greenhouse gas emissions in Australia.

One bright spot is the growth of renewable energy in the power sector which is quite rapid, driven initially by the large-scale renewable energy target for 2020, which the Federal government will not renew. The State of South Australia has a 100% renewable by 2030 target, and others have also ambitious 2030 goals, and as well there are world-leading innovations in the electricity sector to accommodate the rapid growth of variable renewable energy. The outlook is clouded though as many analysts believe further incentives and/or structural changes are needed in the electricity market for recent rates of renewable deployment to continue and grow.

In contrast to the Australian Federal Government, every state and mainland territory government in the country has made either aspirational or legislated commitments toward zero-emissions. Victoria has legislated a net zero emissions by 2050 target, and the ACT has legislated a target to be net zero by 2045.

The “Climate Solutions Package” announced in February 2019 confirms that the Australian government is not intending to implement any serious climate policy efforts. Instead, it wants to meet its targets by relying on carry over units from the Kyoto Protocol, which would significantly lower the actual emission reductions needed. The National Hydrogen Strategy released in November 2019 risks becoming a brown hydrogen strategy in favour of propping up coal and carbon capture and storage technology, rather than focusing on renewable energy and green hydrogen.

The government also wants to continue relying on the inadequate policy instrument, the Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF) now re-named the “Climate Solutions Fund” which is failing to contribute to any significant emissions reductions. Recent ERF auctions have seen fewer emissions abatements contracted, projects have been dropped from the fund for failing to meet abatements, there are issues of additionality, and the fund is dominated by land use sector abatements with a high risk of reversal, for example through bushfires.

The government continues to consider underwriting new coal fired power generation and extending the lifetime of old coal plants - completely inconsistent with the need to phase out coal globally by 2040 and in OECD countries by 2030. If all other countries were to follow Australia’s “Highly Insufficient” current policy trajectory, warming could reach over 3°C and up to 4°C.

While the federal government continues to repeatedly state that Australia is on track to meet its 2030 target “in a canter”, the Climate Action Tracker is not aware of any scientific basis, published by any analyst or government agency, that would support this. The OECD has warned the Australian Government that it will not achieve its target without intensified mitigation efforts. It describes current climate policy as a “piecemeal approach”.

The Government intends to achieve its target mainly through the use of Kyoto carry over - a move that a number of other countries with such carry overs have explicitly rejected. These carry over units make up more than half of the abatement task based on current government projections. Australia’s emissions have been increasing since 2014 excluding the LULUCF sector, when the federal government repealed the carbon pricing system. Emissions are projected to grow through 2030, instead of reducing in line with the 2030 target. While the latest quarterly update shows a slight decrease of total emissions including LULUCF since 2014, based on recalculation of energy consumption data, emissions excluding LULUCF have still increased – by around 1% per year on average since 2014.

The federal government continues to promote coal and is considering to underwrite new coal-fired power generation, which creates barriers to renewable energy and obfuscates its climate policies. The National Hydrogen Strategy adopted in November 2019 has an explicitly technology-neutral approach and only a small portion of funds is allocated to supporting electrolysers to produce hydrogen from water, while there is much higher funding at federal level for one single coal to hydrogen project. In contrast, the reality on the ground at the state level, in public opinion and across the business sector in Australia, is very different. All states (and in addition, the Northern Territory and ACT) now have either aspirational or legislated zero emissions targets, and some have strong renewable energy targets as well as green/renewable energy hydrogen strategies in place. These goals are not without effect, but a federal level commitment to zero emissions and a Paris Agreement consistent 2030 target as well as a renewable energy target beyond 2020 are necessary to ensure a consistent federal framework for a fast transition.

Households across Australia are massively deploying small-scale solar and increasingly combining this with battery storage: about 32% of dwellings in South Australia, 33% in Queensland and 27% of Western Australia had solar PV by 2018, with substantial shares in several other states and territories as well, a trend that is showing no sign of slowing down.

In a recent poll, published in November 2019, climate change ranked second as the most important problem facing Australia, a concern that had increase since 2018. In another survey published just before the elections in May 2019, more than 80% of Australians want the government to enhance their climate action, and more than 90% want to see more renewable energy. Three quarters want to see the Government do more to increase the number of electric cars.

In a survey capturing the views of Australian business and industry, 92% of respondents say Australia’s current climate and energy policy is insufficient to meet the required targets. A further sign of escalating and widespread public disquiet and concern at their government’s lack of action on climate change were the unprecedented, nationwide strikes by school children in late November 2018 and March 2019 followed by larger protests joined by unions and the general public in September 2019 before the UN Climate Summit with an estimated 300 000 people attending in Australia.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter