Country summary

Assessment

Canada continues with the incremental implementation of its Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate, its overarching strategy for reducing emissions, adopted in 2016; often in the face of provincial pushback. The Government is implementing its coal-fired power plant phase-out, but it clearly needs to take more climate action, as emissions are projected to still be above 1990 levels beyond 2030, far from its Paris Agreement target and nowhere near a 1.5˚C-compatible pathway.

The federal government had been facing strong headwinds against climate action at the provincial level, with four provinces (Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, and New Brunswick) challenging the constitutionality of its mandatory federal carbon pricing system. These provinces have no - or insufficient - climate plans and the carbon pricing system applies to them while these court challenges proceed. The first of the cases was recently decided in favour of the federal government and will now be appealed to the highest court in the country, the Supreme Court.

The headwinds reached gale force in April with the election of a conservative government in Alberta. The new government has already begun rolling back the province’s climate policy, while the federal government has stated that it will apply the federal carbon pricing ‘backstop’ to Alberta as well.

Canadians will head to the polls this October to elect their next federal government. It is possible that climate change will be a ballot box issue. There are a number of key pieces of legislation working their way through Parliament to regulate or - ban - oil and gas industry activity that the current government hopes to pass into law before the summer, all of which may have some bearing on the future of the country’s emissions and fossil fuel exports.

Canada, a member of the Powering Past Coal Alliance, adopted performance standards on coal and natural gas-fired power stations in December 2018, which will ensure it meets its 2030 coal phase-out date. However, it is expected that many of the coal-fired plants will be replaced by new natural gas plants or coal-to-gas conversions, all of which run the risk of becoming stranded assets, given that gas has a limited role to play as a bridging fuel.

There have been some positive developments in Canada in the transport sector; though more work is needed. Canada has adopted sales targets for zero-emissions passenger vehicles of 10% by 2025, 30% by 2030 and 100% by 2040. To reach full decarbonisation of the road transport sector worldwide, the last fossil fuel car should be sold before 2035. In the 2019 Federal Budget, the Canadian government allocated $300 million CAD to support consumers and businesses purchase zero-emissions vehicles. The Advisory Council on Climate Action has recommended that the government follow up on these initiatives by imposing supply commitments on car manufacturers.

Canada is also vying for a seat on the UN Security Council for 2021-22 and has stated that climate change would be a key focus of its tenure. The UN Secretary General will host a summit to accelerate action on climate change in September. This is a key opportunity for Canada to demonstrate to the world what leadership on climate change would look like by enhancing its NDC.

In past assessments, the CAT has rated the Canadian NDC as ‘Highly insufficient’ due to the uncertainty around the extent to which it would rely on its forestry sector sink to meet its target. In its latest 2030 projections, Canada has quantified the extent of that contribution for the first time. It is estimated that the forestry sector (LULUCF) will contribute a 7-46 MtCO2e reduction towards meeting its 2030 target. With this greater clarity, the CAT has changed Canada’s rating to ‘Insufficient’.

Based on the policies implemented as of September 2018, we estimate that Canada’s GHG emissions will remain above 1990 levels beyond 2030. In 2020, emissions would be 17–21% above 1990 levels (excluding LULUCF), while in 2030, emissions are projected to be between 5-27% above 1990 levels (excluding LULUCF).

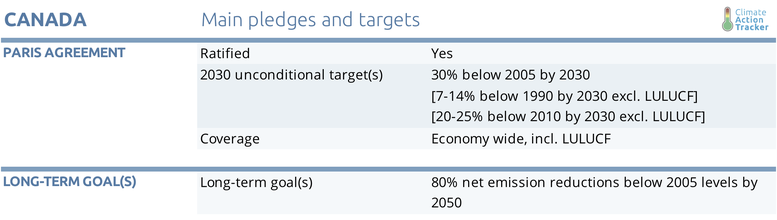

For full details see pledges and targets section.

Full implementation of planned policies would bring emissions down slightly, though they would still remain above 1990 levels. Even with these additional measures, Canada is likely to miss its Paris Agreement (NDC) target.There is no clarity as to how many international credits Canada plans to use to meet its NDC target. The use of international carbon credits implies that a portion of Canada’s emissions reductions will not be met by domestic mitigation efforts.

Canada’s current policies fall within the CAT “Highly insufficient” rating. While the full implementation of its planned policies under the Pan-Canadian Framework would result in further emissions reductions, projected emissions including these additional measures would also fall into the “Highly insufficient” category.

June will be a busy month as the government seeks to close a number of files ahead of the summer recess and pre-election activities. These include:

- A decision by June 18 on whether or not to proceed with the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion. The government purchased the pipeline last year.

- Passing legislation to ban oil tanker traffic off the country’s northern west coast. This legislation was a 2015 election promise of the Trudeau government and is currently before the Senate (the upper house of Parliament).

- Passing legislation on environmental impact assessments that has been opposed by the oil industry.

In early 2019, Health Canada released a new version of the Canada Food Guide. It is the first time the guide has not included a meat category, instead choosing to focus on “protein foods”. It recommends choosing plant-based protein more often than other sources. Reducing emissions from agriculture, including through shifting consumer behavior to a more plant-based diet, will be key to meeting the Paris Agreement’s temperature goal.

Climate policy has been rolled back in Canada’s two highest emitting provinces following changes in government. Last July, newly elected Premier Doug Ford repealed Ontario’s cap-and-trade programme. In April of this year, Jason Kenny, a former federal minister in Stephen Harper’s government, was elected as Premier of Alberta. As part of the election campaign, Kenny promised to roll back a number of the province’s climate policies including the carbon tax and caps on oil sands emissions, as well as replace the entire Alberta Energy Regulator board and stop leasing rail cars for oil transportation. He also vowed to create a ‘war room’ to support the oil and gas sector. True to his promise, Kenny’s government passed the Carbon Tax Repeal Act on June 3 which repealed the province’s carbon tax effective retroactively as of 30 May 2019.

It is an open question whether climate change will be a ballot box issue in the upcoming federal election; however political maneuvering around the issue has already begun. The center-left Trudeau government was forced to vote against a motion to declare a climate emergency by the left-of-center New Democratic Party (NDP), which called for adopting a 1.5°C compatible 2030 target, cancelling the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion and eliminating all federal fossil fuel subsidies. The government’s own motion to declare a ‘national climate emergency’, which would require the government to meet its current target under the Paris Agreement as well as make deeper reductions in line with the Agreement’s temperature goal, was still being debated by Parliament as of 3 June 2019. The Conservatives, the main rival to Trudeau’s Liberals, have yet to release their climate action plan, but have called the carbon tax ‘a betrayal of Confederation’s early promise’ due to the disunity with the provinces it has caused.

The Green Party has had some historic wins lately. A second Green Party member was elected in a federal by-election in early May. In April, the Green Party became the Official Opposition in Canada’s smallest province, Prince Edward Island; another first for the party, though some polls had suggested that they could have formed government. Three Green Party members have held the balance of power in British Columbia’s minority NDP government since the province’s 2017 election.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter