Country summary

Assessment

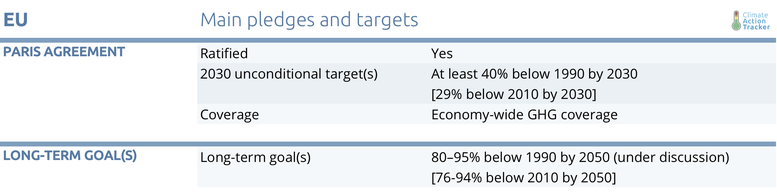

The European Union’s Paris Agreement target of at least a 40% reduction below 1990 levels by 2030 is rated as “Insufficient” and its policies are already on track to meet this target. There is an expectation the EU is planning to put forward a revised and more ambitious 2030 NDC target in 2020.

The European Parliament, the new head of the European Commission, and a number of leaders of the EU member states have already called for increasing the 2030 target to a 55% reduction, which would be a significant improvement - but not yet enough to reach a Paris Agreement compatible emissions pathway.

Available assessments show that the EU can substantially increase its 2030 Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) emissions reduction goal by going beyond the policies it has already adopted and take action congruent with its level of economic development. For example, the 2018 renewable energy and energy efficiency goals would already result in emissions reductions of around 48% by 2030.

After three years of remaining constant, in 2018 the EU’s emissions decreased by around 2.1%, driven mainly by a decrease in the energy sector. Another positive piece of news is that, the reform of the EU ETS – finalised in 2018 – resulted in higher-priced allowances. At least half the proceeds from the EU ETS allowance auction must be spent on climate action, which has increased resources available for low-carbon measures.

The adoption of eight pieces of legislation in the “Clean Energy for all Europeans” package in 2018 and early 2019 has created a framework for the decarbonisation of the energy and buildings sectors by the middle of the century.

New emissions reduction goals for passenger cars, as well as light and heavy-duty vehicles – if effectively implemented – will address increasing emissions from the transport sector. This is very timely as emissions in the transport sector, a fifth of the EU’s overall emissions, increased slightly in the past year.

An increasing concern relates to natural gas. While overall natural gas consumption decreased by 1.8% in 2018, some EU member states are increasing their support for the development of gas infrastructure that will increase EU dependency on energy imports, undermine energy security, lead to stranded assets, and jeopardise meeting the Paris Agreement goals. The decision of the European Investment Bank to stop funding investment in gas infrastructure is a step in the right direction. Shifting resources being used for natural gas infrastructure to achieve the EU’s climate goals is important.

This indicates that the EU’s climate action needs to be accelerated and broadened to other sectors, especially transport and buildings, which requires adopting additional measures in the short term and a clear long-term perspective driving innovation on the continent. Such a long-term perspective could be offered by the 2050 emissions neutrality goal currently under discussion at the European level – after the majority of the EU member states have already adopted such a goal. When, in June 2019, Poland, Czechia, Hungary, and Estonia (which has since withdrawn its opposition), blocked this goal, it was a major blow to the EU’s attempt to re-establish its position as a global leader on climate policy action.

To accelerate decarbonisation – especially in the transport and building sectors – legislation must be efficiently and effectively implemented. Whereas it is up to car manufacturers to find ways to achieve new emissions standards and quotas for zero and low emissions vehicles, national governments need to create a conducive framework for facilitating this process.

Member states and local public authorities also need to promote modal shift by investing in improved public transport and expand rail infrastructure. Implementation of best case practices in the building sector, introducing a pan-European ban on installing oil, gas and coal heating in new builds, flanked with support for low-carbon and zero carbon alternatives such as heat pumps, would not only result in emissions reductions, but would also reduce Europeans’ energy bills and promote the EU’s energy security.

The EU is on-track to meeting its NDC goal of reducing emissions by “at least 40%” and, if it implements current targets in place, may reduce emissions by almost 48% (excluding international aviation) by 2030. According to preliminary data, which includes proxy estimates for Cyprus, Romania and Bulgaria, emissions in 2018 decreased by 2.1%.

In 2018, two thirds of emissions in the EU’s power sector still came from coal-fired power plants. But the role of coal is falling: between 2017 and 2018 emissions from hard coal fell by 9% and from lignite by 4%. To some degree this generating capacity was replaced by renewables, the share of which increased from 30% in 2017 to 32% in 2018.

In the last six months, three additional countries: Portugal, Greece, and Hungary announced a coal phase out or accelerated their existing timeline and will achieve a phase out by: 2023, 2028, and 2030 respectively. With these declarations, only seven EU member states currently operating 43% of the installed coal power capacity are not planning to switch them off by 2030. This includes Poland which makes up half of the EU total installed coal capacity, and Germany which plans to still operate 17 GW of coal capacity after 2030.

The 2018 reform of the EU ETS, combined with higher price of allowances, will incentivize investment into energy efficiency in industry. Some of those investments can be implemented using the resources from the Innovation Fund which must be spent on “industrial innovation in low-carbon technologies and processes”.

Emissions from the transport sector continued to increase in 2018, even if at a smaller pace than in the preceding year – by 0.5%. At the same time the share of renewables in the transport sector also increased: from 7.6% in 2017 to 8.1% in 2018 – significantly below the 10% goal for 2020.

The legislation introduced in 2018 creates the possibility of changing this trend. The 2018 Renewable Energy Directive (REDII) introduced a new goal of a 14% share of renewables in the transport sector by 2030. This target has been flanked by limiting the share of first-generation biofuels. Uncertified biofuels that may create the risk of high indirect land-use change emissions cannot be counted toward meeting the 2030 target. The directive encourages use of energy from second-generation biofuels and electricity.

In December 2018, the European Parliament and the Council agreed on a regulation with the goal of reducing CO2 emissions from new passenger cars and vans, with 2030 goals and an intermediary improvement date. In February 2019, the European Parliament and the Council agreed on emissions standards for heavy duty vehicles.

Support for low carbon modes of transport in some member states has led to an increase in the sale of electrically-chargeable vehicles in the first nine months of 2019 to 2.6% from 2.0% in 2018. However, the share varies significantly by country, with Sweden (an 11% share of electric vehicles in new car sales), the Netherlands (12%) and Finland (6%) making the most progress. However, this was significantly below the values for Norway, where 56% of all vehicles sold in the nine three months of 2019 were electric vehicles.

Some EU member states have already announced plans to ban the sale of internal combustion cars in the coming decades, e.g. Denmark and the Netherlands by 2030, and the United Kingdom and France by 2040. According to CAT estimates, to be compatible with the Paris Agreement, the last internal combustion car needs to be sold by 2035.

The EU will need to take much more decisive action to meet a Paris Agreement-compatible emissions trajectory in its switch to electric vehicles. This may also have positive impact on the EU’s economy: In 2018, the EU’s trade surplus from exporting electric and hybrid electric cars amounted to €3 billion, mainly from Germany, Sweden and the UK.

Underdeveloped charging infrastructure remains a major hindrance to the uptake of electric vehicles. New directives, combined with additional funding from both national and European sources, has led to a significant increase in the number of charging points, from 59,200 in 2015 to 151,700 in 2019.

The EU’s new Energy Performance in Buildings Directive (EPBD), adopted in 2018 obliged each member state to submit a long-term renovation strategy leading to fully decarbonising its building stock by 2050. It remains to be seen whether this will help address the issue of the low rate of deep renovation of the existing building stock. An increase of the renovation rate to 5% would be necessary to make emissions from the building sector compatible with the 1.5°C temperature increase limit.

Since 35% of the EU’s building stock is over 50 years old and much of the overall lifetime reaches beyond 100 years, increasing the renovation rate could significantly reduce energy consumption and emissions. Much more effective has been European legislation dealing with the energy efficiency of household appliances.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter