Policies & action

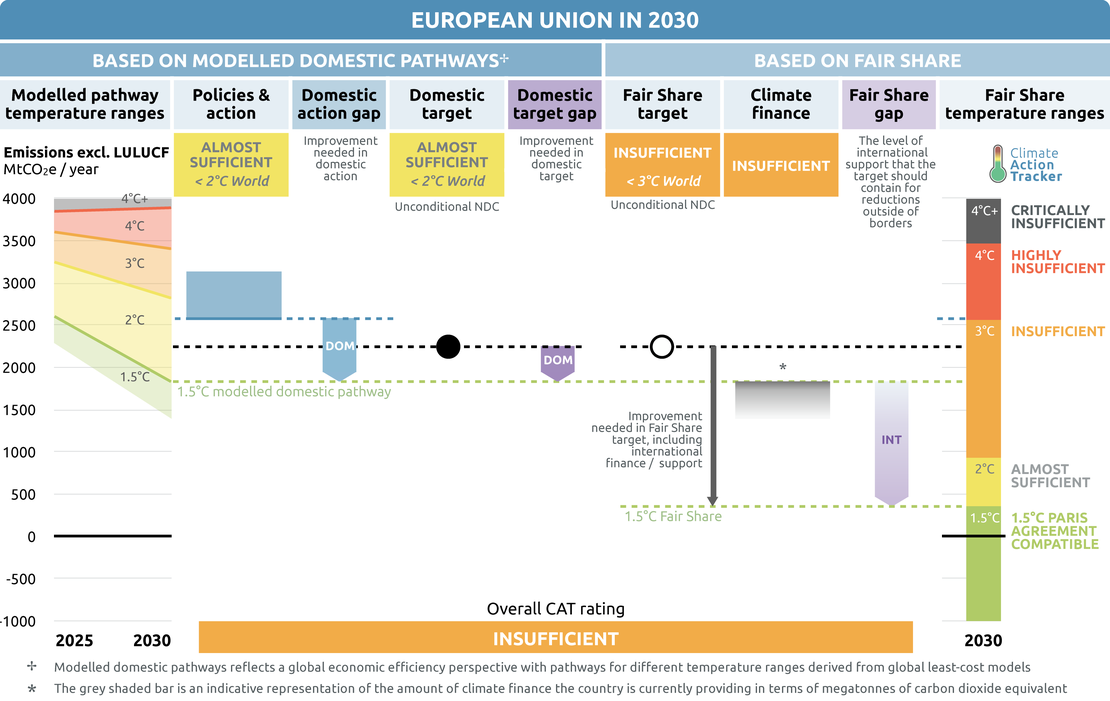

The EU’s emissions have decreased in recent years, with an accelerating trend since 2017 and a major dip in emissions in 2020 as a result of the impacts of COVID-19. Emissions may, however, increase in 2021 due to the economic rebound, and it remains to be seen whether the “Fit for 55” package will be sufficient to instigate a transformative change necessary for 1.5°C-compatibility. While the proposals presented by the European Commission in July 2021 would result in emissions reductions of around 54% below 1990 levels, policies implemented to date would only result in emissions reductions between 36 and 47%. This difference is a result of national policies lagging behind policies adopted at the EU level. We consider the lower emissions bound to be more likely and have based the CAT range on this estimate. The CAT rates the EU’s policies and action as “Almost sufficient”.

The “Almost sufficient” rating indicates that the EU’s climate policies and action in 2030 are not yet consistent with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C temperature limit but could be, with moderate improvements. If all countries were to follow the EU’s approach, warming could be held below—but not well below—2°C.

Further information on how the CAT rates countries (against modelled pathways and fair share) can be found here.

Policy overview

After a slight increase in 2017, EU’s emissions have been decreasing at an accelerated pace: by 2.3% in 2018, 4% in 2019 and—according to preliminary data—at least 11% in 2020. With emissions at around 3.2 GtCO2e in 2020, this would translate to a total emissions reduction of over 34% between 1990 and 2020. As the economy bounces back, emissions may increase in 2021. This increase may only be temporary: current policies adopted at the EU level, especially the renewable energy and energy efficiency goals, should result in emissions decreasing to 2.6 GtCO2e in 2030.

However, many of the policies implemented at the EU level have not yet been implemented by the member states: even if accounting for the overall lower GDP levels resulting from the pandemic, policies implemented by the member states would result in emissions reductions of less than 36% resulting in emissions at around 3.1 GtCO2e – only slightly below levels observed in 2020. Both scenarios are far off the recently adopted emissions reduction goal of “at least 55%” (including LULUCF), or 53.9% excluding LULUCF and intra-EU aviation and maritime.

To close the gap, in July 2021 the European Commission presented its “Fit for 55” package of policy proposals to achieve this new goal (European Commission 2021e). The package includes strengthening the EU ETS, which covers emissions from the electricity sector and industry. Instead of the current emissions reduction of 43% between 2005 and 2030, it should result in emissions reductions of 61% in the same period (European Commission 2021h). The emissions reduction goal in the non-EU ETS sectors has also been increased from 30% to 40% below 2005, with binding national emissions reduction targets between 10% and 50% (European Commission 2021j).

The “Fit for 55” package also includes proposals for a higher share of renewables and increased energy efficiency. The target for the share of renewables in energy consumption has been increased from 32% to 40%, with an additional indicative share of 49% of renewables in the buildings sector. According to the proposal, at least 50% of hydrogen used in the industry should be generated from renewables (European Commission 2021g).

On the package’s new energy efficiency goals, by 2030, EU member states should reduce their total primary energy consumption to no more than 1,023 Mtoe instead of the previous target’s 1,128 Mtoe. Their final energy consumption should not exceed 787 Mtoe. This was around 59 Mtoe less than in the preceding version of the Directive already amended to reflect Brexit (European Commission 2021i; The European Council 2019).

In early 2021, all member states ratified the EUR 750bn NextGenerationEU recovery fund, at least 37% of which has to be spent on climate action (European Parliament Think Tank 2021). In July 2021 the European Commission approved the first National Recovery and Resilience Plans submitted by 12 member states as their basis for spending the resources (European Council 2021). Combined, these countries applied for EUR 392bn, according to the governments’ own estimates, of which 39% is to be spent on climate change mitigation.

Energy supply

In the recent years, emissions from electricity and associated heat generation fell the fastest of all sectors. In 2019 they declined by 14%, resulting in an emissions decrease of 38% below 1990 levels (European Environment Agency 2021a). According to preliminary estimates, in 2020 emissions from electricity sector decreased by nearly 15% compared to 2019. This was due to electricity demand declining by 4%, driven by the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, and a replacement of coal with renewable energy and natural gas (European Commission 2021c, 2021t). As a result, the share of emissions from electricity and associated heat generation in the EU’s total emissions (excl. LULUCF) fell to 21% of total emissions in 2019.

In the last quarter of 2020, electricity consumption almost returned to pre-pandemic levels. This trend continued in the first quarter of 2021, driven by a number of one-off events, such as an exceptionally cold and long winter, and low supply of renewables. As a result, in the first three months of the year, emissions from this sector increased by 9% compared with the same period of 2020 (European Commission 2021s).

In the future, a significant increase in electricity demand driven by economic recovery and acceleration in deployment of electric mobility and heat pumps can be expected. Unless renewables are deployed at a much higher rate and fossil fuels are phased out faster, an increase in electricity demand may also result in a slower reduction in emissions.

Electricity emissions intensity

EU Emissions Trading Scheme

Contrary to the economic crisis of 2008/2009, which resulted in a collapse of the price of emissions allowances (EUA), the COVID-19 crisis led to a comparatively moderate decrease, especially in comparison to other commodities. After falling to EUR 5 per emissions allowance reflecting 1tCO2eq emitted in March 2020, the price of emissions allowances increased steadily to reach EUR 40 in March 2021 and almost EUR 60 in August (EMBER 2021).

To a large degree, this stability and subsequent increase results from moving a certain share of the oversupply of emissions allowances to the Market Stability Reserve (MSR). Between 2019 and 2023, every year a number of allowances corresponding to 24% of their oversupply currently in the market will be moved to the MSR. As a result, between January 2019 and August 2022, allowances corresponding to almost 1.4 GtCO2 — equivalent to 87% of the annual emissions from the EU ETS sector in 2021 — have been, or will soon be, taken off the market (European Commission 2018a, 2019b, 2020j, 2021q).

Further allowances are expected to be removed from the market as the oversupply exceeds the 833 million of allowances threshold. One of the major drivers of this continuous oversupply is the slow decrease in the emissions cap. Between 2013 and 2020, it decreased by 1.74% annually, much slower than the decrease in emissions in the EU ETS sector.

The aforementioned significant decreases in emissions in 2019 and 2020 are twice as high as initially projected by the member states for the whole 2018-2030 period (European Environment Agency 2019). The slight acceleration of the cap decreases to 2.2% annually post-2020 would not substantially improve the situation. For this reason, the proposal of the EU ETS reform tabled by the Commission in July as part of the “Fit for 55” package includes a stricter emissions reduction factor of 4.2% annually starting in 2024, complemented with a one-time decrease of the cap of 117 MtCO2e. This would result in EU ETS decreasing by 61% below 2005 levels, instead of the 43% resulting from the current legislation (European Commission 2021h).

Renewables

In 2020, the share of renewables in the EU27 power sector increased to 39%, almost 4 percentage points above 2019 levels, and exceeding the share of electricity from fossil fuels (European Commission 2020m, 2021t). While part of this increase was due to the increasing capacity of renewables, it was also caused by a decrease in electricity consumption. The latter resulted in lower wholesale electricity prices, which decreased the utilisation rate of fossil fuel-powered power plants. An increase in electricity consumption in 2021 may counteract the impact of this factor. In fact, the share of renewables in the first quarter of 2021 was, at 38%, around 2 percentage points lower than the same period in 2020 (European Commission 2021s).

Newly-installed wind capacity in the EU in 2020 fell slightly in comparison to 2019 and amounted to 10.5 GW, 80% of which was onshore. As a result, EU’s total installed wind energy capacity reached 220 GW, 88% of which is onshore. On average, 15% of electricity in the EU in 2020 came from wind energy, exceeding the share of coal in Q4 of 2020 (European Commission 2021t; WindEurope 2021).

Some countries are planning to increase the role of offshore wind in their future energy mix. In May 2020, Germany increased its 2030 goal for offshore wind from 15 GW to 20GW installed capacity (ZfK 2020). Denmark announced its plans to build two “energy islands” consisting of offshore wind turbines with a combined capacity of 4GW, and a potential to further increase this installed capacity to 10 GW (REcharge 2020). According to the European Commission, between 240 to 450 GW installed capacity in offshore wind will be needed to reach the 2050 emissions neutrality goal (European Commission 2020k). Achieving this goal will be challenging, due to numerous exclusion zones, especially in the North Sea. As a result, only up to 112 GW can be built cost effectively (WindEurope 2020).

To mitigate this issue, in November 2020, the European Commission published its Offshore Wind Strategy with the goal of increasing installed offshore wind capacity in the EU from 12 to at least 60 GW by 2030 and 300 GW by 2050. In addition, at least 1 GW of ocean energy should be installed by the end of the current decade, subsequently scaled up to 40 GW by 2050. For this purpose, the Commission would facilitate cooperation between member states, especially in terms of spatial planning. To reduce the potential for conflicts between offshore wind energy projects and nature protection, the Commission has also published a guidance document on wind energy development and nature legislation (European Commission 2020i, 2020e).

In 2020 newly-installed solar PV exceeded that of wind energy. Despite the pandemic, with estimated installed capacity at 18.2 GW, 2020 was the year with the largest newly-installed capacity except for 2011. Contrary to 2011, which was followed by a significant worsening of the political investment climate, decreased costs of this technology, spread of prosumerism, and an improving policy framework, indicate a further projected increase in installed capacity to 22.4 GW in 2021, 27.4 GW in 2022, 30.8 GW in 2023, and 35.1 GW in 2024 (Solar Power Europe 2020).

To facilitate development of renewables, in September 2020 the EU adopted a regulation implementing the Renewable Energy Financing Mechanism (European Commission 2020h). This Mechanism allows member states to reach their renewable energy goals by funding development of renewables in other EU member states where it could be more cost competitive. To avoid double-counting, the countries in which these projects are hosted cannot account for the installed capacity in their renewable energy goals, but benefit from the emissions reduction, job creation, and reduced energy dependency. The potential of the Mechanism is significantly increased by also opening it to private investors, and the possibility of using resources from the recovery fund. In February 2021 the EU established the European Climate, Infrastructure and Environment Executive Agency (CINEA), which will facilitate implementation of this mechanism, along with other actions (European Commission 2021b).

Coal phase-out

In 2020, electricity generation from coal decreased by 22% and its share in electricity generation fell to 13%, 4 percentage points below the 2019 level (Agora Energiewende and Ember 2021). This decrease was caused by the aforementioned development of renewables, a decrease in electricity consumption, an increase in the price of emissions allowances, and the implementation of coal phase-out plans in some countries. Combined, in 2020 over 12 GW or 9% of the installed coal capacity was retired.

However, at the same time, almost 3GW of new coal capacity was added to the grid: in Germany (1.1 GW), Poland (910 MW) and Czechia (660MW) (BeyondCoal 2021). As a result, the installed capacity decreased by only 7%, much slower than the generation indicating a significant decrease in the utilisation rate.

A coal phase-out is under discussion in all EU countries, except for Bulgaria. However, in many cases, especially in Poland and Germany which, combined, represented 60% of total installed capacity at the beginning of 2021, coal phase-out date is significantly behind what is needed to be compatible with the Paris Agreement.

Germany plans to reduce its installed coal capacity to 17 GW by 2030 and phase it out completely by 2038 at the latest (German Government 2020). However, the recent increase of the German emissions reduction goal to 65%, and resulting sectoral emissions reduction goals, will leave no more space for coal in the power sector in 2030 (Agora Energiewende 2021).

Poland is currently discussing phasing out coal by 2049, with between 38-56% of electricity coming from coal in 2030 and between 11-28% in 2040 (Polish Government 2021; Wyborcza 2021). Such a phase-out is significantly behind what is needed to be compatible with the Paris Agreement which requires emissions intensity of electricity generation to decrease to between 75-80 gCO2/kWh. Due to its high emissions-intensity, coal should be phased out in the EU at the latest by 2030 (Climate Action Tracker 2020).

Natural gas

As most EU member states phase out coal, some of them are increasing their dependency on natural gas and lobby for the utilisation of public money to develop natural gas infrastructure. This topic has been intensively debated in the discussions around the EU’s multi-annual budget and recovery fund with some countries, especially Poland, strongly advocating for continuing support for natural gas infrastructure (Reuters 2021).

The role of natural gas is also being intensively discussed in the context of the revision of the TEN-E Regulation which determines which infrastructural projects can be considered Projects of Common Interests (PCIs). Such projects can be co-funded from the European funds and benefit from fast-track environmental permits. In June the Council accepted a December proposal tabled by the Commission, deciding to allow the use of public funding for natural gas infrastructure until 2027 as long as it is also used to transport some hydrogen (Council of the European Union 2021b; European Commission 2020l).

It also agreed an exception to allow funding for two new pipelines exclusively for the transport of natural gas: the EastMed pipeline that would transport natural gas from offshore Israel to Cyprus, Greece, and elsewhere in the EU, and the Melita pipeline, which would transport gas from Sicily to Malta. It is now up to the European Parliament to improve the text.

While the revision of the TEN-E Regulation will influence which transboundary projects will receive EU support, under the sixth PCI list in 2023, by the end of 2021, the Commissions is set to publish the fifth PCI list. The current list of candidate projects includes 74 natural gas investments, the construction of which would cost a combined EUR 30bn, complemented by estimated EUR 780m annual operating costs (CAN Europe 2021; ENTSOG 2021). If all projects were accepted as PCIs, most of the resources would be spent in Greece, Bulgaria, and Poland.

Continued use of public funding for such projects not only extends the EU’s dependency on fossil fuels, but it also undermines EU’s energy security. The lack of need for new natural gas infrastructure was confirmed by an assessment conducted before the COVID-19-driven economic recession (Artelys 2020). Over a year later, such investments are even more difficult to justify due to the significant potential for reduced demand for natural gas in the coming years.

After an increase by 2% in 2019, natural gas consumption fell by 3% in 2020 (European Commission 2020m, 2021r). While this reduction could to a large degree be explained by economic recession, the decreasing costs of renewables, and implementation of the renovation wave announced recently by the European Commission, offer the potential to significantly reduce natural gas demand in the power and buildings sectors. In the medium and longer-term, deployment of green hydrogen could replace significant portions of natural gas consumed in the chemical industry sector. In fact, scenarios compatible with the EU’s new 2030 goal result in natural gas demand decreasing by almost 14% from 2020 levels (European Commission 2021f).

To avoid a carbon lock-in, a complete divestment from fossil fuels, including a commitment to refrain from new investment in natural gas infrastructure, is necessary. The decision of the European Investment Bank to phase out lending for all fossil fuel projects, including, from 2021, natural gas , is a step in the right direction, even if a belated one (EIB Group 2020). The EU should ensure that no public resources are used to support unnecessary and harmful investments that counter EU’s decarbonisation efforts.

Industry

After a decrease of 2.7% in 2019, emissions from the industry sector constituted 9.4% of all EU’s emissions (excl. LULUCF). This is roughly the same share as in 1990, indicating a similar speed of emissions reduction as overall emissions (European Environment Agency 2021b). A much more significant decrease is expected in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19-induced recession. However, this decrease is likely to be temporary, and emissions are likely to rebound as the economy recovers.

To decouple emissions from economic growth, in March 2020, the European Commission published its New Industrial Strategy for Europe with a number of measures that would allow industry to contribute to achieving the “climate neutrality” goal (European Commission 2020b). Some of these measures have been further elaborated in the Chemicals Strategy published in October 2020 (European Commission 2020f). In May 2021 the Commission updated the Industrial Strategy, reflecting the changes brought about by the pandemic (European Commission 2021w).

The update of the EU’s Industrial Strategy was accompanied by Staff Working Document “Towards Competitive and Clean European Steel”, which pointed out that the steel sector, responsible for 5.8% of the EU’s total emissions (including indirect emissions), could be “one of the first hard-to-abate sectors to produce green products”. The document listed a number of measures planned or already taken to accelerate innovation in the steel sector and deployment of low carbon steel. Apart from different streams of funding (e.g. Innovation Fund, InvestEU Fund, Recovery Fund), it also listed measures that could increase demand for low carbon steel (e.g. Construction Products Regulation, Sustainable Products Initiative, Public Procurement policies) (European Commission 2021v).

While emissions from the industry sector are covered by the EU emissions trading scheme and thus are affected by the increasing price of emissions allowances, the impact of this instrument is lessened by the fact that companies producing products on a so-called “leakage list” receive free allowances up to the average emissions of the 10% most efficient installations in the sector, or subsector, potentially affected by the risk of carbon leakage. Increasing stringency of the criteria that need to be fulfilled by a product to be listed as affected by carbon leakage resulted in a decrease in the share of allowances received for free by the manufacturing industry from 80% in 2013 to 30% in 2020 (European Commission 2020d).

One of the measures suggested in the Commission’s New Industrial Strategy, and also referred to in the European Green Deal, is the introduction of a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) – an additional charge on energy-intensive products from countries with no or very lax climate mitigation measures. In July 2021 the Commission tabled a proposal on the CBAM that would require EU importers of certain energy-intensive products to purchase CBAM Certificates, mirroring the price of emissions allowances traded in the framework of the EU ETS. The introduction of the mechanism should result in a steady phase-out of free allowances (European Commission 2021m).

In July 2020, the Commission presented its hydrogen strategy with the goal of realising 40 GW of installed electrolyser capacity in the EU by 2030 to generate green hydrogen from renewable sources of energy. This is to be complemented by a further 40 GW of electrolyser capacity installed in neighbouring countries.

The combined investment needed to develop this capacity, scale up solar and wind generation, and develop the necessary electricity and dedicated pipeline connections has been estimated to be between EUR 309 - 447bn. An additional EUR 11bn would need to be invested in retrofitting the existing hydrogen production plants with carbon capture and storage infrastructure (European Commission 2020a). While hydrogen can be used in many different sectors, e.g. as storage in the electricity sector, mobility or even heating, its first destination will be the industry sector, especially chemical and petrochemical, where it is currently used as feedstock. In the future, its role will also increase in the steel sector where hydrogen can be used instead of carbon monoxide in a reduction process (Hydrogen Europe 2020).

Industry emissions intensity (per GVA) MER

Transport

Contrary to the general trend of decreasing emissions, after an increase by 0.1% in 2018 emissions in the transport sector continued their upward trend, increasing by 0.8% in 2019. As a result, the share of emissions from this sector also increased significantly: from 14% of all emissions in 1990 to 23% in 2019. As the transport sector—with the exception of intra-European aviation—is not covered by the EU ETS, the European Union and its member states are trying to reduce emissions from the sector in four ways: (i) adopting sectorial renewable energy targets, (ii) introducing CO2 emissions standards for new vehicles, and (iii) increasing the share of zero and low emissions vehicles, and (iv) encouraging a modal shift, which also has an important role to play, particularly from road and air to rail transport.

Sectoral renewable energy targets

The 2009 Renewable Energy Directive introduced a 10% target for energy from renewable sources in transport by 2020 (European Parliament and the Council of the European Union 2009). In 2019, the EU member states were far from achieving this goal, with only 8.4% of energy consumed in the sector coming from renewable sources, an increase by 0.1% on 2018 (European Environment Agency 2020).

The 2018 Renewable Energy Directive (REDII) introduced a new goal of a 14% share of renewables in the transport sector by 2030. However, the proposal for the revision of the directive presented by the Commission in July 2021 replaces this goal by a greenhouse gas emissions intensity target. In addition, the share of biogas and advanced biofuels should increase to 2.2% and the share of renewable fuels of non-biological origin should increase to 2.6% by 2030 (European Commission 2021g).

In July 2021 the Commission also proposed a new regulation aimed at increasing the role of sustainable fuels in aviation. According to the proposal, their share should increase from 2% in 2025 to 5% in 20230, 32% in 2040, and 63% in 2050. An increasing role in achieving these goals should be played by synthetic aviation fuels, mainly hydrogen generated from renewables (European Commission 2021n).

For maritime transport, the proposal of the FuelEUMaritime Regulation does not propose any specific share of renewables. However, their uptake is promoted by a requirement to decrease emissions intensity by 2% in 2025, 6% in 2030, 26% in 2040, and 75% by 2050. In addition, when at berth, ships will be required to connect to onshore power supply, if such is available. To reduce emissions-intensity, ships may also use onboard solar for electricity generation or wind for assisted propulsion (European Commission 2021p).

CO2 emissions standards for vehicles

Emissions intensity of land-based passenger transport

The binding regulation obliges car manufacturers to decrease average emissions of new passenger cars and vans by 15% from 2025. From 2030, an average new passenger car is to emit 37.5% less CO2 than in 2021, whereas the emissions standards for new vans are to improve by 31%. The amendment of the regulation tabled by the Commission in July 2021 strengthened the 2030 target and added emissions reduction for new vehicles of 100% in 2035 (European Commission 2021k; European Parliament and the Council of the European Union 2019).

These emissions reductions cannot be directly applied to the existing 95 gCO2/km limit for passenger cars for 2021 and 147 gCO2/km limit for vans in 2020: due to numerous exceptions and different methodology, the real average emissions of new vehicles will very likely be higher. Recently, it has become clear that the increasing stringency of the emissions standards was accompanied by an increasing gap between test results and real-world performance: according to some estimates this gap reached 42% or 31 gCO2/km per vehicle in 2015 (Transport&Environment 2018). To limit and possibly remove this gap, the law replaces the current testing regime with the Worldwide Harmonised Light Vehicles Test procedure (WLTP) and empowers the Commission to take the steps necessary to implement this procedure (European Commission 2017).

In 2019, the EU was far from reaching its emissions standards for passenger vehicles. On average, new cars registered in the EU27+UK emitted 123 gCO2/km. The most polluting car fleets are in Bulgaria (138 gCO2/km), Luxembourg, Slovakia (133 gCO2/km each) Poland, Hungary, Lithuania (132 gCO2/km each), Lithuania (132 gCO2/km), and Germany (131 gCO2/km). The cleanest car fleets, that are still above the benchmark, are in Portugal (109 gCO2/km), France, and Ireland (114 gCO2/km). Only in the Netherlands is the emissions-intensity from new cars slightly below 100 gCO2/km (ACEA 2020a).

In February 2019, the European Parliament and Council agreed on emissions standards for heavy duty vehicles. Emissions from new vehicles should decrease by 15% in the period 2025-2029 and by 30% from 2030 onwards, in comparison to emissions of the new vehicles sold between July 1, 2019, and June 30, 2020. The regulation also includes a 2% benchmark for the share of zero and low-emission vehicles (ZLEV). Whereas failing to meet this benchmark does not result in any negative consequences, exceeding it leads to more lenient emissions standards for the remaining vehicles (The ICCT 2019).

Promoting low-carbon vehicles

Zero emission fuels for domestic transport

One of the options available for car manufacturers to reduce the average emissions of their cars is to increase the availability and sale of zero and low-emissions vehicles. The emission standards regulation also includes a mandatory quota for the share of zero- and low-emission vehicles (ZLEV) defined as emitting less than 50 gCO2/km for new passenger cars and light commercial vehicles. According to the regulation, in 2025 at least 15% of passenger cars and light vans must be ZLEV. By 2030 this share should increase to 35% for passenger cars and 30% for light vans (European Parliament 2019a).

In 2020, the share of new electrically chargeable vehicles in the EU reached 10%, driven mostly by additional subsidies, decreasing costs, and increasing opportunities for EV charging. However, only 52% of these vehicles were battery-only vehicles, a decrease from 64% in 2019 (ACEA 2020b, 2021). The remaining electrically-chargeable vehicles were plug-in hybrids that can still largely run on petroleum, while benefitting from significant state subsidies.

In the first half of 2021 the share of electrically chargeable vehicles increased to 15%, but with significant differences between the member states: with a 40% EV share in Sweden, 28% in Finland, and 27% in Denmark, the Nordic countries recorded the highest levels of EVs, followed closely by Germany with 22% and the Netherlands with 20%. At only 1.7%, Lithuania recorded the lowest share of EVs, but Cyprus (1.8%), Romania (1.9%), Croatia (2.1%), Slovakia and Slovenia (2.6% each), Estonia (2.7%), and Poland (2.9%), were not far ahead.

However, the increase was driven mostly by the sale of plug-in hybrids: only 44% of EVs sold in the first six months of 2021 in the EU were battery-only vehicles. In Belgium and Finland (26% each), and Denmark (29%), their share was among the lowest. At the same time, all EVs sold in Lithuania and Romania were battery-only vehicles (ACEA 2021).

The EU is trying to stimulate deployment of clean vehicles market by introducing binding quotas for clean vehicles procured by public authorities. In February 2019, the EU Parliament and Council agreed on an amendment to the Directive on promoting clean and energy efficient vehicles. The Directive requires public authorities procuring vehicles (e.g. for public transport) to take their CO2 emissions and the emissions of other pollutants into account in their investment decisions. It also sets a minimum share of clean heavy-duty vehicles (trucks and buses) in the total number of heavy-duty vehicles contracted by member states.

These shares differ depending on the member states and types of vehicles. For example, in the period 2021-2025, between 24% (Romania) and 45% (majority of the EU member states) of buses procured by public communities should be clean or zero emissions. For the period 2026-2030, these shares increase to between 33% and 65% (European Parliament 2019b).

The European legislation, combined with the additional funding from both national and European sources, has led to a significant increase in the number of charging points in the EU27, from 48,00 in 2015 to almost 275,000 in mid-2021. An increasing share of these charging stations are fast charging stations (>22 kW): their share increased from 7% in 2015 to over 9% in 2021. However, the speed of increase in the number of EVs exceeded that of the charging points. As a result the number of the number of EVs per charging point kept increasing from five in 2017 to 11 in 2021 (European Alternative Fuels Observatory 2021).

Underdeveloped charging infrastructure remains a major hindrance to the uptake of electric vehicles. In July 2021 the Commissions tabled a proposal that would replace the Directive on the Deployment of Alternative Fuels Infrastructure from 2014 with a regulation that includes a number of mandatory national targets, e.g. for for each battery electric light-duty vehicle registered in their territory, a total power output of at least 1 kW must be provided through publicly accessible recharging stations. For plug-in hybrids this factor amounts to 0.66 kW for each vehicle. There should also be a recharging pool every 60 km of TEN-T corridors consisting of fast charging points—at least 300 kW from 2025 and at least 600 kW from 2030.

Additional targets are specified for hydrogen charging stations, charging stations for heavy-duty vehicles. The proposal also requires the development of charging stations for LNG for heavy duty vehicles and ships “unless the costs are disproportionate to the benefits, including environmental benefits“. This requirement could significantly increase dependency of the transport sector on natural gas (European Commission 2021o).

Modal Shift

The EU aims to strengthen the position of railways in comparison to the other modes of transport, by increasing competition between the operators and investing in rail transport infrastructure, as well as other measures. However, these efforts still did not have an impact on shifting freight transport from road to rail: between 2013 and 2018, the share of freight transported by rail remained constant at 18.7% (Eurostat 2020).

To improve the situation, the European Commission proposed an amendment of the 1992 European Combined Transport Directive in 2017. However, the negotiations between the Parliament and the Council did not make any progress since the proposal was tabled (European Parliament Think Tank 2019). A revised proposal of the Directive on Combined Transport will be presented in 2021 as part of the European Green Deal (European Commission 2019a).

Whereas in passenger transport the number of passenger-kilometres increased slightly over the last decade, this increase was much faster than in the case of rail. This is especially the case in Eastern European countries, where a shift from train to plane could be clearly observed with more passenger-kilometres travelled by plane than by train in most of the countries. Due to the massive investment in new motorways, co-financed to a large degree from European sources, the popularity of passenger cars increased significantly. This has been accompanied by only a modest improvement in railway infrastructure (Climate Analytics et al. 2020).

The increase in the role of aviation has been strongly undermined by the COVID-19 related limits on international travel and it remains to be seen how soon and whether it will fully recover. In the meantime, the funding to be made available on climate action in the framework of the Multiannual Financial Framework and NextGenerationEU Recovery Fund presents the opportunity to replace domestic and, in some cases, intra-EU flights with rapid train connections.

Buildings

After a decrease by 3.6% in 2018, direct emissions from fuel consumption in households decreased by only 1.8% in 2019. The share of these emissions in the EU total EU remained relatively stable, at around 9% (Eurostat 2021b). However, this excludes indirect emissions, e.g. from electricity generation. With indirect emissions and including commercially used buildings, this sector is responsible for 36% of emissions of the EU’s emissions and 40% of energy consumed (European Parliament 2021).

In 2019 the majority of these emissions were coming from natural gas consumption, which accounted for 32% of the EU final energy consumption in households, as much as electricity and derived heat combined. Petroleum satisfied almost 12% of energy needs, whereas coal was still responsible for almost 3% of final energy combusted with low efficiency in households, almost all of it in Poland. The share of energy from renewables in energy consumed in the households increased to 28% in 2019 (Eurostat 2021a).

The Energy Performance Buildings Directive (EPBD Directive), first adopted in 2010 and amended in 2018, regulates emissions from the buildings sector and obliges member states to introduce minimum energy performance requirements and ensure that, from 2021, all new buildings are “nearly zero energy buildings” (NZEB). While defining an NZEB as a building with a very high energy performance, whose energy needs are covered largely from renewable sources of energy, the EU left the definition of the exact energy consumption level of such buildings to its member states (European Parliament and the Council of the European Union 2010).

However, the directive failed to significantly accelerate the renovation rate, which remained at around 1% of the buildings stock (European Parliament 2021).To increase the renovation rate, in October 2020 the Commission launched its ‘Renovation Wave’ with a number of goals and measures to reduce emissions and energy consumption in the buildings sector e.g. providing more adequate and targeted funding, increasing the availability of energy-efficiency and recycled buildings materials, introduction of stricter and mandatory minimum energy performance standards, and increasing the role of digitalisation and renewables.

As a result, by 2030, at least 35 million buildings are to be renovated and renovation rate doubled. These measures are to be implemented by the revision of the EPBD Directive, for which the Commission will table a proposal by the end of 2021, and further development of eco-design and energy efficiency measures (European Commission 2020c).

Meanwhile, a proposal amending the Energy Efficiency Directive, tabled by the Commission in July 2021, included some of the measures mentioned in the Renovation Wave Strategy, e.g. creation of a one-stop shops for the provision of technical, administrative, and financial knowledge about increasing energy efficiency and house renovation.

Member states should also ensure that a mechanism is introduced that would ensure that both, tenants and home owners benefit from the implementation of energy efficiency measures. It also encourages national governments to set up Energy Efficiency National Funds to implement energy efficiency measures (European Commission 2021i). The proposed amendment of the Renewable Energy Directive, tabled simultaneously, proposes that member states adopt indicative targets for the share of renewables in the buildings sector consistent with the share of renewables at 49% for the EU as a whole (European Commission 2021g).

An additional tool that should facilitate emissions reduction in the buildings sector is the proposal to adopt an adjacent EU ETS for the buildings and transport sector. The Commission’s proposal, also presented in July 2021, suggests creating such an EU ETS (“ETS2”) to start operating in 2025. It should result in emissions reductions from these two sectors by 43% below 2030: 18 percentage points below the emissions reduction in the already-existing EU ETS covering electricity and industry sectors (European Commission 2021h).

At the same time, emissions from the buildings are also to be covered by the amended Effort Sharing Regulation which includes binding emissions reduction targets for sectors not covered by the initial EU ETS. These targets result in average emissions reduction at 40% - instead of 30% in the initial regulation (European Commission 2021j).

Buildings emissions intensity (per floor area, residential)

Agriculture

In 2019 emissions from agriculture constituted slightly less than 11% of the EU’s total emissions—a share that increased modestly from 10% in 1990 due to a slower rate of emissions decrease than overall emissions. After a significant decrease in the early 1990s especially in the Eastern European countries, emissions from this sector decreased much slower in the 2000s and remained relatively stable in the 2010s (Eurostat 2021b).

Currently, emissions from the agricultural sector are covered by the Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR), which covers all sectors, except for those covered by the EU ETS and LULUCF. According to the Regulation, the combined EU emissions from the ESR sectors are set to decrease by 30% by 2030 in comparison to 2005, with different goals for different EU member states (European Parliament and the Council of the European Union 2018). In July 2021 the Commission presented a proposal that increases this goal to 40% to reflect the higher overall emissions reduction goal. According to the proposal of the ESR regulation, the emissions from agriculture should be climate-neutral by 2035 (European Commission 2021l).

Furthermore, in its proposal the Commission suggested to increasingly deploy carbon farming schemes and certification for carbon removals through 2030. These schemes will especially promote the creation of new business models that are focused on increasing carbon sequestration in agriculture and other land types. Land users (i.e. farmers and foresters) are expected to avoid further depletion in their carbon stock, especially in soils. The carbon farming initiative will be introduced by the end of 2021 and the proposal for carbon removals will be introduced in 2022.

Forestry

The land use, land-use change and forestry sector (LULUCF) has since 1990 constituted a sink of emissions averaging around 300 MtCO2e. The only countries for which LULUCF does not constitute a sink are Denmark (average 4.4 MtCO2e), Ireland (4.8 MtCO2e), and the Netherlands (5.8 MtCO2e). At the same time, Spain, France, Poland, and Sweden reported sinks between 30 and 40 MtCO2e (Eurostat 2021b).

The EU Regulation for the Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry regulates the accounting of the GHGs emissions and removals from the LULUCF sector. It allows the use of net removals from this sector to comply with the targets in the non-EU ETS sectors by up to 280 MtCO2 from 2021–2030 (European Commission 2016). The Regulation includes a no-debit rule meaning that emissions from deforestation could be offset by either afforestation or improved management of existing forests (European Commission 2016). However, this target is weakened by the possibility of using 2021-2025 LULUCF emissions reductions to offset emissions in the second half of the decade.

In July 2021, the Commission tabled a proposal amending the LULUCF Regulation, under which the flexibility on the accounting of emission reductions from managed forests will still be in place in the period 2021 - 2025 and will be adjusted in 2026 in line with the European Climate Law. The proposal also included a goal of increasing the sinks to 310 MtCO2e equivalent in the LULUCF sector in 2030.

This target will be distributed among the Member States as annual targets trajectory based on the reported greenhouse gases inventory for the years 2021, 2022, and 2023 (European Commission 2021l). According to the European Climate Law, only 225 MtCO2e can be used to account for meeting the new EU Emissions reduction goal. Should the 310 MtCO2e goal be adopted, this would mean that the EU has an additional, separate target for LULUCF sink of around 85 MtCO2e. This constitutes a step in the right direction in terms of separating emissions reduction and emissions sinks.

Waste

Emissions from waste management decreased by a third between 1990 and 2019 – much faster than total emissions. As a result, their share in total emissions also decreased: from 3.6% to 3.2% (Eurostat 2021b). Waste is covered by the Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR), next to transport, buildings, and agriculture. According to the currently binding legislation, combined emissions from these sectors need to decrease by 30% between 2005 and 2030. The Commission’s proposal amending this regulation increases this emissions reduction goal to 40% (European Commission 2021j).

The main legislation influencing EU’s waste management policy is Waste Framework Directive which aims at reducing the amount of waste that lands on the landfills and contributes to climate change by promoting recycling and reuse of products (European Parliament and Council 2008). In addition, the EU is facilitating a transition towards circular economy. In 2015 it adopted respective action plan with a list of 54 actions that would i.e. make products more durable and make it easier to repair, upgrade, or remanufacture after their use. Products’ labeling should also make it easier for the European customers to make more informed decisions when taking into consideration products’ environmental impact (European Commission 2015).

In March 2020 the EU adopted new Circular Economy Action Plan. The plan adapts EU’s waste policy to the climate neutrality goal by 2050 goal by building on and concretizing many of the suggestions made in the initial action plan from 2015. It also suggests integrating life cycle assessment in public procurement. The impact of circularity on climate change mitigation should also be reflected in modelling tools applied at the national and European levels, and taken account for in the revisions of the National Energy and Climate Plan (European Commission 2020g).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter