Policies & action

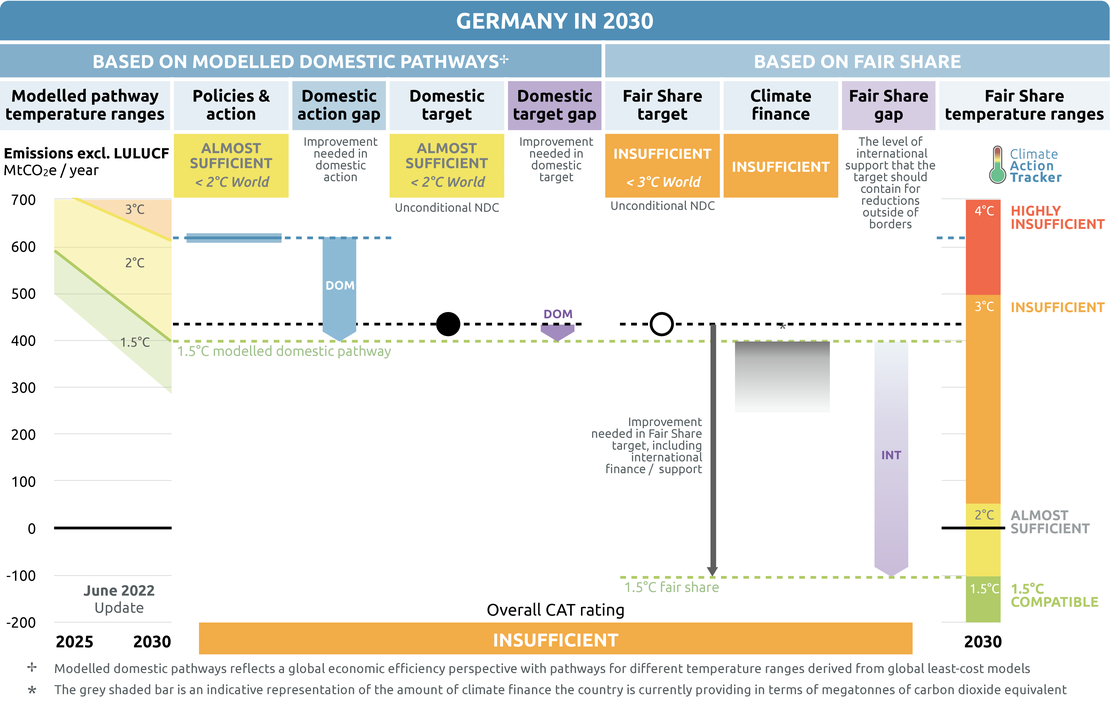

We project that implemented policies and actions will lead to emissions reductions of between 49% - 51% below 1990 levels by 2030 excl. LULUCF. This falls short of Germany’s 2030 target of at least a 65% reduction below 1990 levels.

Our recent estimate of the implemented legislation (not the plans) projects higher 2030 emissions than our previous assessment, despite progress in policy making. Reasons are a smaller impact of the COVID-19 crisis on the economy than expected, a corrected estimate for industry and higher electricity demand. Already the 2021 emissions were higher than expected last year. We rate Germany’s policies and actions until 2030 “Almost sufficient”.

In addition, we provide an estimate of “new government plans”, as the new German government is providing an increasing number of detailed plans in different sectors to reach the 2030 target, which are not yet implemented in legislation. If these planned measures detailed in the coalition contract and legislative proposals were effectively implemented, Germany would reduce emissions to 57% to 63% below 1990 according to the Climate Action Tracker quantification, and thus get close to its 2030 target. The CAT rating would remain “Almost sufficient”; it would require at least a 69% reduction for 1.5°C compatibility.

Further information on how the CAT rates countries (against modelled pathways and fair share) can be found here.

Policy overview

The new German government, in power since December 2021, is significantly accelerating domestic climate policy implementation.

It has restructured the ministries and their staffing: there is now one Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate, which lifts climate policy up on the agenda. The Ministry of Foreign Service is now responsible for climate change negotiations, giving it prominence. Baerbock, the Minister of Foreign Affairs ran as candidate for chancellor for the Green party. The ministry for transport and for finance in turn have ministers from the Liberal Party, which has a far more lenient approach to climate policy than the Greens.

In the coalition contract, the new government decided not to raise the ambition of the mitigation target, but promised at the press conference announcing the agreement that the measures adopted in the coalition agreement would overachieve the target (ARD, 2021).

With a “programme for immediate climate action”, the government wants to quickly advance legislation in favour of renewable energy, building renovations, industrial innovation and the development of a green hydrogen industry. The “Easter package”, that the cabinet has agreed on and that is expected to pass parliament before the summer, foresees a substantial push for renewable energy. The government has also revised its funding for efficient buildings, with the idea of increasing the effectiveness of the finance with regards to emissions reductions. For more detail, see the sector information below.

To cope with the Russia’s unlawful invasion of Ukraine and related energy security issues, Germany has introduced a set of measures, some of which are counterproductive to climate policy. This includes measures related to transport, a sector that is already lagging in climate action, but also the planned fast expansion of LNG import infrastructure, which risks a lock-in of fossil fuels, and brings into question Germany’s long-term ambitions for GHG neutrality.

Germany has, over decades, imported a substantial amount of its natural gas supply from Russia (55% of the demand before the crisis), and also through its engagement in the Nordstream pipelines, actively contributed to locking itself in to Russian gas supply, strengthening the position of the Russian government. As a result of the Russia’s Ukraine invasion Germany needs to urgently find ways to reduce its gas consumption as fast as possible and safeguard not only to the country’s energy security but also geopolitical stability in Europe.

Renewable energy is a priority for the German government and it has already increased its targets originally agreed on in the coalition agreement. Energy efficiency is also addressed in some areas, although at lower intensity than the measures for renewable energy. The economics ministry issued plan for efficiency of activities, which is indeed a plan that is - for now - non-binding, and not yet translated into legislative proposals (BMWK, 2022a). Avoiding overconsumption is currently not a focus of German policy making.

The new government is also looking into ramping up LNG import capacities and “long-term energy partnerships” with other suppliers. Most recently, Chancellor Scholz announced his intention to support fossil gas extraction in Senegal with the intention of importing LNG to Germany. With this aim, he suggests rolling back the Germany’s COP26 commitment to no longer finance fossil fuels abroad.

Energy supply

According to the German government targets legislatively anchored in the climate law, the energy sector (electricity and heat supply) will have to limit its GHG emissions to 108 MtCO2e by 2030. This is a reduction of 62% below 1990 levels. In 2021, total emissions from the energy supply sector stood at 247 MtCO2e, an increase of 27 MtCO2e or 12.4% compared to the previous year. After falling by 16% in 2020, emissions from electricity generation only also rose again by 26 MtCO2e or 14% in 2021 and resulted in a total of 214 MtCO2e emitted (Agora Energiewende, 2021b; Ember, 2022).

The significant rise in emissions in 2021 is due to increased use of coal and decreased use of natural gas in the second half of the year, driven by the sharp rise of gas prices. The main reasons for the increased use of fossil energy sources for electricity generation is the much lower level of electricity generation from renewables (– 17.5 TWh) compared to the previous year, particularly lower wind power generation, and an increase in gross electricity consumption by 13.5 TWh (Federal Environment Agency, 2022a).

Overall, Germany’s electricity mix is still heavily dependent on fossil fuels. In 2021 half of electricity was generated by fossil sources. Coal generation had halved since 2015 but its share in total electricity generation rose again to 29% in 2021 (23% in 2020), while natural gas currently makes up 16% of Germany’s electricity mix (Ember, 2022).

The currently legislated slow and gradual coal phase-out by 2038, large new investments into gas infrastructure, and difficulties with the expansion of renewable energy capacity pose a risk to Germany’s ability to reach its longer-term targets for 2030 and 2045, and a burden to global emissions budgets which require a coal phase-out by 2030. The new government intends to phase out coal by 2030 by supporting renewables and making coal power obsolete, but not through changing the phase-out schedule, which remains at 2038.

Measures adopted up to September 2020 would lead to a remaining 183 - 186 MtCO2e by 2030 for the energy sector according to the last official government estimation, leaving an emissions gap of between 75-78 MtCO2e to reach the updated target (Federal Environment Agency, 2020).

We calculate that the new government’s plans (Easter package) would lead to 95 – 127 MtCO2e in 2030, meaning that in the best case, the planned measures would overachieve the electricity sectoral target (see assumptions for further details).

Prices for CO2 emission allowances in the EU emissions trading system (EU ETS) that also apply to German coal power plants have risen more or less continuously over the course of 2021. In May 2021, the EUR 50/tCO2 mark was reached for the first time; in the period from September to November, prices hovered at a level of around EUR 60/tCO2 and exceeded EUR 80 in December (BDEW, 2022b). On an annual average in 2021, emission allowances cost around EUR 54 /tCO2 compared to 25 €/t CO2 in 2020, an increase of about 120%. With such high prices, coal becomes very unattractive compared to renewables, but with current high gas prices, coal is more attractive than gas (Gray, 2022).

Coal phase-out

Around two-thirds of the emissions from electricity generation in 2021 are attributable to lignite and hard coal-fired power plants. Coal-fired power generation has halved over the past five years, but still contributed 29% of total electricity generation in 2021 (Agora Energiewende, 2021a; Ember, 2021b). That means that in 2021 about 18% of total German emissions still came from power and heat generation from coal-fired power plants. Roughly one third of CO2 emissions from coal-fired electricity generation in Europe is from Germany (IEA, 2021a).

In July 2020, the German government adopted a coal exit law that stipulates the last coal-fired power plant will be closed by 2038 at the latest. The compromise was found only by compensating the affected regions (with EUR 40bn) and the affected companies operating the coal-fired power plants (with additional EUR 4.35bn) (Agora Energiewende, 2019; Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie, 2019). In November 2020, the European Commission approved the proposed competitive coal phase-out tender mechanism under the coal exit law (European Commission, 2021). In the first rounds of auctions between September 2020 and March 2022 the Federal Network Agency awarded bids with a combined capacity of around 9.7 GW (Bundesnetzagentur, 2022b). The operators received up to EUR 165,000 for each MW of installed capacity that will be phased out by the end of 2022 at the latest and, in 2021, a total of 5.8 GW coal capacity was retired (Bundesnetzagentur, 2021, 2022b; Global Energy Monitor et al., 2022).

The new government coalition now aims to phase out coal by “ideally” 2030 and has moved its review of the phase-out date forward to 2022, which the coal exit law originally prescribed for 2026 (Federal Ministry of Economics and Climate Protection, 2022a). The formal phase-out plan has not yet been changed, but the government expects that CO2 prices and availability of renewables will drive coal out earlier than in the phase-out law.

The government's plans would have a significant impact on emissions. Germany is the largest coal operator in Europe and the EU’s total coal-fired power generation would drop from 282 TWh to 118 TWh in 2030, equal to emissions savings of about 148 MtCO2e (Ferris, 2021). Moving forward the phase-out date to 2030 is sorely needed - projections show that coal-fired power plants operating as planned under the German coal exit law would emit almost 2 GtCO2e cumulatively between 2030 - 2038 (DIW, 2020). This is roughly half of Germany’s carbon budget under the CAT’s estimation of Germany’s “fair share” contribution towards limiting global warming to 1.5°C.

Research shows the German government is overcompensating the coal companies by almost EUR 2bn when comparing the difference between a generous, rule-based compensation and the actual proposed lump-sum compensation (Matthes et al., 2020). A study even shows that when correcting for problematic assumptions taken by the Economic ministry, compensation could be reduced to EUR 343m (Ember, 2021a). Coal-fired power plants will probably not be economically viable in the short run anyway, due to increased prices of CO2-certificates, which are expected to further increase in the context of the European Green Deal (Fraunhofer ISE, 2020; Matthes et al., 2020) .

Natural gas

Natural gas is currently providing 16% of the electricity in Germany and its share in total energy supply has increased over the last decade to about 27% in 2020 (Ember, 2022; IEA, 2021b). Besides the electricity sector, much fossil gas is used for heating and in industry, as a source of energy and as a feedstock in the chemicals sector.

In the power sector, in recent years, the gas fleet has operated at below 50% of its capacity(Ember, 2022). The need for expansion of gas-fired electricity is unclear, but increasing the capacity of renewables does not generally cause more demand for natural gas. If renewables are expanded as planned and coal and nuclear phased out, the existing gas-fired power plants could provide the remaining electricity, if they run on a higher load. This is, however, unlikely, as with the large share of variable renewables, the flexibility of other sources in the system will need to increase and they will need to cover peaks in demand, rather than run long hours. Building new gas peaker plants is expensive. While power plants that operate as combine heat and power (CHP) generation are more efficient, they are much less flexible, and are only able to react to variations in the grid to a limited extent.

Studies on the need for the expansion of gas diverge. There is currently no public government document that describes a plan to tackle this issue. An EWI study shows expansion of additional 23 GW (Gierkink et al., 2021). This study is based on the Dena Leitstudie (2021), which has been criticised for its assumption of a high gas demand (Germanwatch et al., 2021). Another study supported by the Federal Association for Renewable Energy estimates additional 10 GW by 2030, all of which are CHP plants (Böttger et al., 2021). The German government should carefully consider which combination of storage capacity, grid investments, demand management and additional gas peaker plants is most (cost) efficient when moving to a high share of renewable energy, while phasing out coal and nuclear energy.

As a reaction to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the need to reduce dependency energy imports from Russia, the German government is pursuing partnerships with other potential suppliers. These include Qatar, the US and, most recently, Senegal (Tagesschau, 2022). Such long-term partnerships not only risk a lock-in of the German economy into the unsustainable use of a fossil fuel, but also threatens the necessary transition in the partner countries and raises questions around international justice and geopolitical risks.

German gas imports from Russia have remained largely at stable levels since the invasion started and storage is at roughly 45% currently (end of May 2022) (Bundesnetzagentur, 2022a).

Renewables

Pushing renewable energy is a priority of the new German government and is approached in a very comprehensive manner through increased targets and planned legislative measures, that aim at overcoming very specific challenges for renewable energy in Germany. This approach, if implemented effectively, will be a game changer for renewable energy in Germany, and could serve as a good example for other countries.

Germany's binding target of an 18% share of gross final energy consumption under the EU's Renewable Energy Directive (RED) for the year 2020 was exceeded (19.3%) and in 2021 continued to rise slightly (19.7%) (Federal Environment Agency, 2022b).

Electricity generation from renewable energy declined by seven percent in 2021 due to a comparatively poor wind year. At the same time, the expansion of onshore wind energy plants stagnated in recent years (see Figure 1). The renewable share of gross electricity consumption fell accordingly from 45.3% in 2020 to 42.6% (Federal Ministry of Economics and Climate Protection, 2022a).

The German government aims to raise the share of electricity generated from renewable energy to 80% of gross electricity consumption by 2030 compared to the earlier 65% target set in the Climate Action Programme 2030 (Federal Ministry of Economics and Climate Protection, 2022a). This goal is not yet fully aligned with the Paris Agreement but is getting close: studies suggest that the share of renewable electricity in total generation needs to reach 85-100% by 2030 to be compatible with a 1.5°C pathway (Figure 2).

Accordingly, the government has increased the targeted capacity additions for solar PV, wind onshore and offshore. In its “Easter package”, the government even increased the targeted capacity further than the original plans of the coalition, to a total of 360 GW cumulative installed capacity by 2030 (30GW offshore wind, 115 GW onshore wind, 215 GW solar PV)(Federal Ministry of Economics and Climate Protection, 2022b). To reach these targets, a fourfold increase of the annual capacity additions for solar is needed, and the annual capacity additions for wind need to increase by 7.5 by 2030.

The Easter package (Federal Ministry of Economics and Climate Protection, 2022b) also comes with comprehensive legislative proposals to revise the Renewable Energy Law (EEG) and the wind energy offshore law (WindSeeG) that support the targets, for example through determining that renewable energy installations are of public interest so they can be prioritised over other issues, particular support for rooftop solar PV, increasing the focus on participatory models for citizens, supporting storage and redirecting biogas towards flexible power generation.

The latter point can be highlighted: in recent years Germany has promoted electricity generation from biomass through financial support per unit of electricity produced. As a result, biogas plants have run at almost full capacity throughout the year, without any consideration of contributing to the flexibility of the grid or seasonal storage (Fraunhofer ISE, 2022). Biogas as a resource for system integration of a high share of variable renewables is a much more effective and sustainable use of a good that is often at competition with food production.

Additional revisions of legislation are planned that would increase the area available for renewable energy capacity additions, protect end users of price volatility and facilitate the grid expansions required for a high share of renewable electricity.

In June 2020, Germany released its National Hydrogen Strategy (German Government, 2020f) that focuses on “green” hydrogen produced by using renewable energy. The strategy sets out 38 measures for the period up to 2024 to support hydrogen production and to identify fields of application (German Government, 2020f).

The government hopes to establish hydrogen as an alternative energy carrier to enable the decarbonisation of hard-to-abate sectors, like industry and aviation (Amelang, 2020). In addition to existing government programmes, the COVID-19 stimulus package includes a further EUR 9bn investment into supporting the technology development and hydrogen production in both Germany and partner countries, and to support a switch in industry processes. Planning with “green” hydrogen also implies an increased need for renewable energy.

Industry

The industry sector is responsible for more than a fifth of Germany’s total emissions. Sectoral emissions declined by 30% from 1990 to 2008 and have been stable since. However, emissions still need to be reduced by 59 MtCO2e to meet the new sectoral target of 119 MtCO2e/year by 2030. The measures introduced until September 2020 would lead to a level of 143 MtCO2e/year by 2030, leaving a gap of 24 MtCO2e (Federal Environment Agency, 2021a).

In 2021, emissions from the industry sector stand at 148 MtCO2e, an 5.5% increase from 2020 levels and just below the sectoral emissions budget of 182 MtCO2e (Federal Environment Agency, 2022). According to the German Federal Environment Agency, the rise in emissions is mostly due to catch-up effects in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and an increased use of fossil fuels. The most significant percentage increase was in the steel industry, where crude steel production rose by roughly 12% while emissions in the manufacturing industry rose by around 6% (Federal Environment Agency, 2022).

(see Assumptions sections for further details).

A large share of direct emissions in industry goes back to the use of fossil gas. A third of the gas in Germany is used by industry. 55% of that is used for process heat, 20% for electricity production for own use, 11% as raw material for ammonia (mostly for fertilisers), hydrogen and methanol and 7% for heating buildings(Zukunft Gas, 2022) .

So far the actions of the new German government on industry have been vague and not very concrete. The most tangible measure is that the economics ministry wants to offer “Carbon Contracts for Difference” to interested companies (BMWK, 2022b), which guarantee a certain fixed price for a product if the market should not reach this level. This innovative policy would allow industry to make significant investments in new CO2 free technologies, without the risk that the product will fail on the market.

In 2021, the previous German government introduced numerous measures aimed at accelerating decarbonisation of the industry sector. The measures included a EUR 2bn financial aid scheme supporting research on innovative technologies for decarbonising heavy industry, a strategy for climate-friendly steel production and an additional EUR 5bn on the climate-friendly restructuring of the steel industry between 2022 and 2024 (German Government, 2020d; German Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, 2021; German Ministry of the Environment, 2021). While these are steps in the right direction, they are unlikely to be enough to achieve the full decarbonisation of the sector by 2045. For this purpose, clear implementation plans, targets, and incentives as well as technology breakthroughs are required.

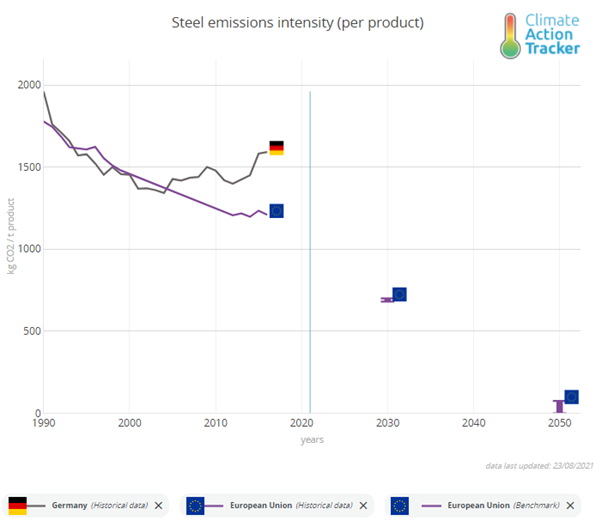

For steel production, the largest emissions source within Germany’s industry sector, the CAT’s analysis indicates that to be compatible with the Paris Agreement the emissions-intensity of steel would need to be reduced by 45% by 2030 below 2015 levels for EU countries (Figure 3). Reaching these benchmarks requires a clear policy framework, including, for example, carbon contracts for difference, green hydrogen quotas, and investment security (Agora Energiewende, 2020).

Transport

The transport sector is responsible for about 20% of Germany’s emissions. According to the German government targets, transport sector emissions need to be reduced by 44% below 1990 levels, meaning they would have to fall to no more than 85 MtCO2e in 2030. While at 148 MtCO2e in 2021, they are still close to 1990 levels today and roughly 3 MtCO2e above the sector’s emissions budget for 2021 (Federal Environment Agency, 2022a).

The transport sector is responsible for well over a quarter of total energy consumption and in 2021 only 6.8% of total final energy consumption in the sector came from renewable sources (Federal Environment Agency, 2022a). In 2020, transport sector emissions decreased by 11.4% compared to 2019 mainly due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic (Federal Environment Agency, 2021b).

While traffic from passenger cars continues to be lower in 2021 than pre-pandemic levels, the sector’s emissions have again increased by 1.2% compared to 2020 (Federal Environment Agency, 2022a). The main reason for that is freight traffic which has risen back to slightly above 2019 levels (Federal Environment Agency, 2022a). Measures adopted up to September 2021 will lead to greenhouse gas emissions of 126 MtCO2e by 2030, leaving a gap of 41 MtCO2e over the rest of the decade (Federal Environment Agency, 2021c). This is the largest gap of all sectors in Germany.

The new government’s plans include specific targets for the transport sector, including 15 million electric vehicles on the road, one million public charging points, doubling the volume of passenger rail transport and a 25% modal split share of rail freight (Federal Ministry of Economics and Climate Protection, 2022a). However, the new government has not designed policy instruments for achieving those targets and the overall emissions budget set in the climate law. Most of the funding announcements are also still subject to funding reservations (Öko-Institut e.V., 2022).

Besides these specific targets, the new German government intends to support the European Commission's Fit for 55 package to adjust CO2 fleet target values for new passenger cars and light commercial vehicles, including an increase in the ambition level in 2030 (emissions reductions by 55% compared to 2021) and a continuation to 2035 (emissions reductions of 100% compared to 2021) (Öko-Institut e.V., 2022). From 2035 onwards, only CO2-emission-free passenger cars and light commercial vehicles can be newly registered in the EU without incurring any penalties. With its decision to back the EU proposal, Germany now could sign up to the Glasgow declaration of clean transport, which it has not yet signed(UK COP 26 Presidency, 2022). Additional measures include a toll for trucks above 3.5 t which is dependent on CO2 emissions as well as an adjustment of existing environmental bonuses and premiums for electric vehicles.

The CAT estimates that these measures would lead to emissions levels of between 96 and 122 MtCO2e in 2030 under the “new government plans”, leaving a gap of 11 to 38 MtCO2e to the sectoral emissions budget set in the climate law (see Assumptions sections for further details). It should be noted that the ongoing crisis and inflicted uncertainty around fuel prices make it particularly difficult to project emissions for the transport sector.

The coalition agreement largely ignores any measures to equalise the costs between road and rail transport and explicitly excludes a speed limit. According to Federal Environment Agency research, a speed limit on highways of 130, 120 or 100 km/h would result in emissions savings of 1.5, 2 and 4.3 MtCO2e/year, respectively, which is equal to 5-14% of emissions from passenger cars and light commercial vehicles on highways (Federal Environment Agency, 2022c).

In light of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, gas prices for households roughly doubled in the first months of 2022 compared to the previous year (BDEW, 2022a). Gasoline for cars also got more expensive. As a reaction, the German government adopted two relief packages in March and May 2022. For the transport sector these included lowering the fuel tax for gasoline and diesel to the European minimum, which will reduce the price by 30 EUR ct/litre and 14 EUR ct/litre, respectively.

Such a wholesale subsidy undermines climate action and mostly rewards those consuming the most. A targeted support to those who cannot afford high energy prices in the form of independent payments, combined with development of low carbon alternatives, especially public transport, would be much more effective and fairer approach.

As part of the overall package the coalition also agreed on a EUR 9 monthly bus and rail pass for local public transport that will be available for every citizen for a period of three months from June to August 2022 (German Government, 2022).

Public transport

The plans of the new government include doubling the volume of rail passenger transport by 2030 compared to today’s level, increasing the capacity and attractiveness of public transport, and raising the share of journeys undertaken by bicycle or on foot, but remain vague when it comes to specific instruments and finance for achieving these goals (Federal Ministry of Economics and Climate Protection, 2022a). To date, rail accounts for only 8% and cycling plus walking for only 6% of total passenger transport (Federal Ministry of Economics and Climate Protection, 2022a).

As part of the Climate Action Programme 2019 Germany has increased its budget for the improvement and expansion of the public transport system to EUR 1bn per year from 2021 and EUR 2bn from 2025, which, while welcome, is small in size compared to overall infrastructure investment needs for decarbonising the transport sector. Deutsche Bahn, the national rail company, and the government further plan to invest EUR 86bn into the rail network by 2030. Additional measures include the reduction of the value added tax from 19% to 7% on long-distance tickets from January 2020 and the support of model projects, including an annual public transport ticket for EUR 365 (German Government, 2019).

The impact of these measures is difficult to quantify but it can be assumed that they will contribute to emissions reductions and modal shift to some extent. It seems unlikely that the measures will lead to a substantial transformation of the sector. As part of the COVID-19 recovery package the government has pledged to provide additional financial support for public transport in the order of EUR 2.5bn to municipalities and to inject further EUR 5bn into Deutsche Bahn for railway modernisation, expansion and electrification (CarbonBrief, 2020; German Government, 2020a).

Electrification of passenger vehicles

The new German government has set a goal of 15 million electric passenger vehicles in its fleet by 2030, which was previously set at seven to 10 million and is less than a third of the 48 million cars on the road today (Federal Ministry of Economics and Climate Protection, 2022a). While the registration of new electric vehicles has significantly increased, by January 2022 only 618,500 EVs were on the road (Emobil, 2022).

The government target of 15 million electric vehicles by 2030 is not sufficient to meet the sectoral emissions budget for passenger transport (52 MtCO2e by 2030) set in the climate law but would still lead to levels of 64 MtCO2e in 2030 (Koska & Jansen, 2022). The target would need to be increased to at least 20 million electric vehicles to meet the emissions budget. Research finds that the measures in the coalition contract are too weak to meet the 15 million target (Koska & Jansen, 2022). Consequently, additional measures are needed to accelerate EV uptake, including the introduction of a registration tax for CO2-intensive cars, bringing the ban on new registrations of cars with gasoline and diesel engines forward from 2035, a higher CO2-price or a comprehensive reform of company car taxation.

In Germany, registrations of alternatively powered vehicles increased by 30% in the first quarter of 2022 compared to 2021 despite disruptions in the supply chain due to the Russian invasion (ACEA, 2021). Overall, new car registrations fell by 4.6% in the first quarter of 2022 compared the previous year (ACEA, 2022) . The share of electrically chargeable vehicles in total registrations increased from 3% in 2019 to almost 24% in the first quarter of 2022 (ACEA, 2022). 55% of these vehicles were purely battery electric vehicles (BEV’s), an increase from the 45% share in the same period in 2021 (ibid).

In 2019, the government agreed with the German car industry to increase the financial incentive for newly-purchased BEVs from EUR 3,000 to EUR 6,000 (EUR 3,000 from the Government and EUR 3,000 from manufacturers). The incentive was also expanded to cover vehicles above EUR 40,000, which were previously not eligible. However, the premium may lead to hidden price increases, given half of it is covered by the producers themselves. Small start-ups cannot cross-subsidise this premium from other business and may need to raise the price of the EVs, potentially cutting the premium in half. In addition, as part of the COVID-19 stimulus package, the government has decided to exempt EVs from vehicle tax until 2030 and has doubled the state’s share of the buyer’s premium for EVs until the end of 2021 from EUR 3,000 to EUR 6,000 (German Government, 2020b).

In 2020, the COVID-19 stimulus package introduced a EUR 2bn programme for investments into new technologies by car manufacturers, and another EUR 2.5bn for expanding EV charging infrastructure and supporting electric mobility research.

Although more than 13,000 new charging stations were installed in 2021, with a total of 49,000 chargers in the grid by December 2021, the government still falls short of its target of 50,000 public charging stations by the end of 2020 (BDEW, 2022b; German Government, 2019). The Climate Action Programme also stipulates that the number of public charging points for electric vehicles should increase to one million by 2030, which was reinforced by the new government in 2022 with a focus on developing fast-charging infrastructure. All petrol stations will be required to have EV charging stations and if the set goal cannot be achieved through market mechanisms, the government is considering further regulatory measures. On a per capita level, this would result in 604 chargers/million people in 2030, still significantly lower than Norway, where there are 3,400 public chargers/million people by August 2021 (NOBIL, 2021).

The number of private charging stations has also increased significantly since the Government introduced a financial support scheme in November 2020. Since then, more than 300,000 requests for support have been registered and the initial funding pot has been increased from the original EUR 200m to EUR 400m (BDEW, 2021). This is an important development since nine out 10 charging processes take place at home or at work (BDEW, 2021).

Carbon price

As of 2021 emissions trading was introduced on transport fuels in Germany. Certificates were distributed for a fixed price of EUR 25/tCO2 in 2021, have been increased to EUR 30/tCO2 in 2022 and will be rising to EUR 55/tCO2 in 2025. After 2025 new allowances will be auctioned in a corridor of EUR 55 to EUR 65/tCO2e (German Government, 2020e). All proceeds from the pricing system will be re-invested into climate protection or returned to citizens. If more allowances are needed than available, additional allowances can be purchased from other EU member states. Hence the effectiveness of the instruments also depends on the stringency of measures in other member states.

The impact of this new system is very difficult to predict. An initial price of EUR 25/tCO2e will only have limited effect. If demand supersedes the amount that is provided at a fixed price and allowances need to be purchased from other member states, this could see prices reaching relatively high levels.

Aviation and shipping

The new German government plans to include the support of ambitious electricity-based fuel (PtL) quotas in the aviation and shipping sectors in order to stimulate a market ramp-up in line with the EU Fit for 55 package (BMWK, 2022b). To meet the set targets, production capacities for green hydrogen and green synthetic kerosene are planned to significantly increase.

To avoid airlines from offering “dumping prices”, the Climate Action Programme of the old government stipulates that tickets must not be cheaper than the costs of taxes, surcharges and other fees combined. In April 2020, the German government further increased the aviation levy and almost doubled taxes on short-haul flights. For flights up to 2,500 km the levy increased from EUR 7.50 to EUR 13.03, from 2,500 – 6,000 km from EUR 23.43 to EUR 33.01 and for flights above 6,000 km from EUR 42.18 to EUR 59.43 (Entwurf Eines Gesetzes Zur Änderung Des Luftverkehrsteuergesetzes, 2019). Compared to the UK where the levy for flights above 2,000 km is EUR 83.35, this is still quite low.

In May 2020, the German government agreed on a EUR 9bn pandemic rescue package for the largest German airline Lufthansa. In sharp contrast to bailout packages by other European countries, this bailout came without any additional environmental requirements (Wilkes, 2020). As part of the COVID-19 stimulus package the government has put forward EUR 1bn for modernising aviation, accelerating a shift towards more efficient aircraft fleets, and another billion for modernising shipping (German Government, 2020a).

Buildings

In 2021, the buildings sector was responsible for 15% of Germany's total emissions. Although emissions have decreased by 3.3% compared to 2020, now standing at 115 MtCO2e, the sector has again exceeded its annual emissions budget in 2021 (113 MtCO2e) as defined in the climate law (Federal Environment Agency, 2022b). Emissions have declined by 22% from 2010-2021 and still need to reduce further to meet the new sectoral target of 67 MtCO2e/year by 2030. The measures introduced until September 2020 would only lead to a level of 91 MtCO2e/year by 2030, leaving a gap of 24 MtCO2e (Federal Environment Agency, 2020; Kemmler et al., 2020) .

To close this gap, half of the additional funds from the Climate Emergency Programme 2021 have been earmarked to promote the energy-efficient refurbishment of buildings and the installation of energy-efficient heating systems (German Government, 2021b). The programme also includes plans to raise the minimum energy standards for new buildings. The impact of these additional measures on emissions in the sector has not yet been quantified. A recent Climate Action Tracker report stresses the importance of a comprehensive approach to increasing efficiency and speeding up decarbonisation, particularly in the buildings sector (Climate Action Tracker, 2022; German Ministry of Finance, 2022; SPD/ DIE GRÜNEN/ FDP, 2021).

In 2022, the new government has announced a series of instruments for the transformation of the buildings sector, either explicitly mentioned in the coalition agreement or included in the second energy cost relief package (German Ministry of Finance, 2022; SPD/ DIE GRÜNEN/ FDP, 2021). The most relevant measures are the 65% renewable requirement for new heating systems from 2024 onwards, an announced heat pump campaign as well as the requirement that the EU EH-70 standard should apply to the refurbishment of existing buildings (Federal Ministry of Economics and Climate Protection, 2022a; Öko-Institut e.V., 2022) .

Other important instruments are the abolishment of the renewable energy levy, the commitment of the German government to actively support the Fit-for-55 legislative proposals of the European Commission for the buildings sector, and the introduction of municipal heat planning (Federal Ministry of Economics and Climate Protection, 2022a; Öko-Institut e.V., 2022).

The plans of the new government are, however, unlikely to put the buildings sector on a pathway compliant with the climate law. It lacks a clear concept on how private renovation activity in the building stock is to be increased to the target of a 2% renovation rate and in most areas, there is no sign of an improvement in the funding and incentive landscape, which has so far failed to achieve its goals (DIW Econ GmbH, 2021). The CAT estimates that these measures would lead to emissions levels of between 69 and 91 MtCO2e in 2030 under the “new government plans”, leaving a gap of 2 to 24 MtCO2e to the sectoral emissions budget set in the climate law (see Assumptions sections for further details).

The German government is committed to reducing the carbon footprint of the buildings sector by about 40% by 2030 below 2015 levels. However, to be 1.5°C-compatible, the CAT benchmark analysis for EU countries indicates that by 2030, emissions in the German buildings sector should be around 60% lower in residential buildings, and 75% lower in commercial buildings compared to 2015 levels.

Carbon price

As of 2021 emissions trading was introduced on fuels in the buildings sector in Germany. Certificates were be distributed for a fixed price of EUR 25/tCO2 in 2021, have been increased to EUR 30/tCO2 in 2022 and will be rising to EUR 55 /tCO2 in 2025. After that, new allowances will be auctioned in a corridor of EUR 55 to EUR 65/tCO2 (German Government, 2020e). If more allowances are needed than available, additional allowances can be purchased from other EU member states. All proceeds from the pricing system will be re-invested into climate protection or returned to citizens. To ensure that the costs of climate protection do not put a burden on people with low incomes, housing allowances were increased by ten percent from January 2021 onwards (German Government, 2019).

The impact of this new system is very difficult to predict. The initial prices will only have limited effect. For the purchase of natural gas, the EUR 30/tCO2 means a surcharge of 0.650 EUR ct/kWh (incl. VAT). In the long term, prices could reach quite high levels, if demand superseded the amount that is provided at a fixed price, but again, this is difficult to predict (BDEW, 2022b).

Building retrofits

Germany has a long tradition in providing low interest loans for renovation of buildings and support of renewable heating systems, especially for new buildings. As part of the COVID-19 recovery package the German government is providing an additional EUR 2bn for energy-efficient renovations of buildings, and another EUR 4.5bn as part of the Emergency Program 2022 (German Government, 2020c, 2021b)(German Government, 2020b).

As a new measure of the Climate Action Program 2020, energy-efficient retrofits of buildings used by the owner became tax-deductible in 2020. In addition, a scrap premium of 40% is paid on exchanging an oil heating system by a new one based on renewables or gas with a share of renewables.

According to the plans of the new government, from 2024, all newly installed heating systems must run 65% on renewable energy. While the details of this threshold are yet to be developed, they could lead to an effective ban of gas heating system also for retrofitted buildings.

Agriculture

Since 1995 emissions from the agriculture sector have remained almost unchanged. The sectoral target for the agriculture sector is to emit no more than 56 MtCO2e/year by 2030. In 2021, emissions stood at 61 MtCO2e, well below the sectoral emissions budget of 68 MtCO2e for that year. Livestock numbers continued to fall - cattle livestock decreased by 2.3% and swine by 9.2% compared to 2020, resulting in less emissions from manure management (a 4% decrease from 2020 levels) (Federal Environment Agency, 2022a).

However, the significant reduction in total sectoral emissions is mainly due to methodological improvements in the calculations rather than actual policy action. With the measures introduced in September 2020, emission levels are expected to still stand at 63 MtCO2e in 2030, leading to a gap of approximately 7 MtCO2e/year to the sectoral target of 56 MtCO2e (Federal Environment Agency, 2021c, 2022a).

After the change in government in December 2021, the agriculture ministry is now led by Green politician Cem Özdemir. He has used his maiden speech in parliament to outline an ambitious climate protection plan, including countering the use of energy-intensively produced pesticides and mineral fertilisers, and aiming for 30% of food in German supermarkets to be organic by 2030 with a strategy to follow (Bateman, 2022; German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture, 2022b). The coalition contract has also set a target of 30% of all farming to be organic by 2030, which was previously set at 20%, but is missing a strategy or concrete measures to reach this goal (SPD/ DIE GRÜNEN/ FDP, 2021).

Further, the new government wants to strengthen plant-based alternatives and advocate for the approval of innovations such as alternative protein sources and meat substitutes in the EU, and is planning to introduce mandatory animal husbandry labelling, including transport and slaughter, in 2022 (SPD/ DIE GRÜNEN/ FDP, 2021). However, important financial incentives such as exempting animal products from the reduced VAT rate, which could motivate a change in behaviour towards reduced consumption of animal products, are not included (DIW Econ GmbH, 2021).

Overall, the plans of the new government do not yet include enough new and concrete policy measures to expect a clear improvement compared to current emissions projections (DIW Econ GmbH, 2021; Öko-Institut e.V., 2022). For the “new government plans” the CAT therefore estimates that emissions in the agriculture sector will reach a level of 57 - 63 MtCO2e in 2030, leaving a gap of 1 - 7 MtCO2e/year to the sectoral target (see Assumptions sections for further details).

In June 2021, the German parliament passed a legislative package for the national implementation of the EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), taking the first steps in the move away from area-based farming subsidies to payments made depending on the environmental and climate performance of farmers in a new system of so-called eco-schemes (Deutscher Bundestag, 2021).

Germany will redirect 25% of the money from direct payments into eco-schemes, while the European Parliament and other actors had advocated for a minimum of 30% (Appunn, 2021). The package has been met with criticism from the German farmers association and environmental organisations alike, not being substantial enough to ensure meaningful climate action and even disadvantaging grassland and eco farms in its current set up (Koch, 2021; Lehmann, 2021).

In February 2022, one of the first official actions of the new minister was to hand in the strategic plan on the distribution of the EUR 30bn in subsidies from the CAP in the 2023-2027 funding period to the European Commission (German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture, 2022a). While about half of the subsidies were earmarked for “environmental, climate and biodiversity protection objectives”, German environmental organisations still warn that the strategic plan is too weak to meet the targets for climate protection and biodiversity, would miss the 30% target for organic farming specified in the new government’s coalition agreement and would likely not be approved by the European Commission (Appunn, 2022b).

Forestry

Forests cover approximately 11.4 million hectares in Germany, which equates to one third of Germany's national territory. The LULUCF sector has been a net sink of CO2 emissions. However, in 2020, the removal of CO2e has been reduced by 60% compared to 1990 (11 MtCO2e compared to 27 MtCO2e) while forests are increasingly suffering from the impacts of climate change. Even with the measures introduced up until September 2020, the sector would turn into a net emissions source and emit 22 MtCO2e/year by 2030, clearly missing the target of being an emissions sink of 25 MtCO2e by 2030 set in the updated climate law (Federal Environment Agency, 2022a; German Government, 2019, 2021a). The new government’s plans do not add any additional measures but state that “existing measures must be consistently pursued and further complemented” (Federal Ministry of Economics and Climate Protection, 2022a).

In January 2022, the new environment minister Steffi Lemke announced a ten-year EUR 48m funding programme for peat soil protection, focusing on areas in the largest moorland regions, which will be rewetted and alternative cultivation will be tested (Appunn, 2022a; Federal Ministry for the Environment Nature Conservation Nuclear Safety and Consumer Protection, 2022).

In 2021, the German government set up a EUR 1.5bn support programme for reforestation, managing damage and adjusting forests to the changing climate after the Forest Condition Report found that more trees died in 2020 than any year before (German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture, 2020; Nijhuis, 2021). The support programme includes EUR 500m for climate action premiums that award forest owners who, for example, increase the CO2 storage capacity of their forests or ensure harvested wood is used in durable wood products (German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture, 2021).

Measures previously proposed in the Climate Action Programme 2019 include increasing efforts for reforestation and the adaptation of forests to changing weather patterns, increasing the capacity of soils as carbon sinks and better protection of moors and wetlands, in a general effort to make carbon sinks more resilient to extreme weather events (German Government, 2019). The COVID-19 recovery package further included an additional EUR 700 million for the conservation and sustainable management of forests (German Government, 2020a).

Waste

In 1990 the German waste sector emitted 38 MtCO2e (3% of total emissions). By 2021, emissions were at just 8 MtCO2e - a decrease of 78% and contributing only about 1% of total emissions (Federal Environment Agency, 2022a). This was achieved mainly by ending the disposal of untreated residential waste and the increased utilisation of energy and materials from waste (Federal Environment Agency, 2017). Since 2005 landfilling of biodegradable waste is prohibited in Germany. The continued downward trend in 2021, minus 4% compared to 2020, is essentially determined by decreasing emissions from landfilling (Federal Environment Agency, 2021a).

The Climate Action Programme 2019 proposed three additional measures for the waste sector: 1) continued support of small landfill aeration projects, 2) additional support for large landfill aeration projects and 3) optimised landfill gas capture (German Government, 2019). If these measures were to be implemented emissions in the sector would reach 5 MtCO2e in 2030 leaving a gap of 1 MtCO2e for meeting the sectoral target of 4 MtCO2e set in the climate law.

To close this gap the new government wants to develop a National Circular Economy Strategy and adapt the current legislative framework for waste management (Federal Ministry of Economics and Climate Protection, 2022a). Since these measures are rather vague the CAT assumes a range of 4 to 5 MtCO2e in 2030 for the “new government plans” (see Assumptions sections for further details).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter