Policies & action

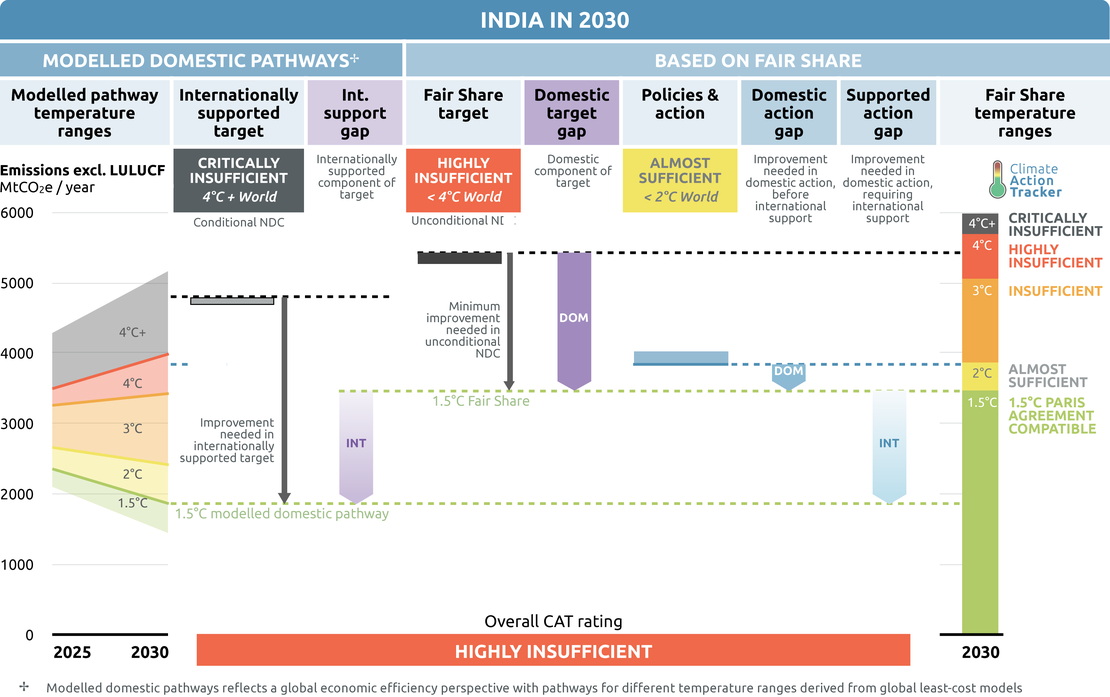

India’s emissions will be between 3.8 and 4 GtCO2e in 2020 under current policies and action. The CAT rates India’s policies and action as “Almost sufficient” indicating those are not yet consistent with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C temperature limit but could be with moderate improvements. The median value of emissions falls under the rating “Insufficient”, but the lower bound of this current policy emissions estimate falls just inside the ‘Almost sufficient’ range, when rated against a fair share contribution. We consider the lower bound to be more likely and use it as the basis for our ratings.

The economic standstill brought about by COVID-19 has hit the Indian economy heavily. The latest IMF data shows that GDP declined by 7% in 2020, impacting production, consumption and electricity demand (IMF, 2021). It is projected that GDP will increase by 8-12% in 2021 from its 2020 level, but as the pandemic is not yet over, uncertainty around such estimates remains. It is further predicted that the emissions from power generation will increase by 1.4% in 2021 following a rebound in coal demand to meet rising electricity demand (IEA, 2021a; IMF, 2021; World Bank, 2021b). An accelerated transition away from coal towards renewable energy in line with the Paris Agreement would come with large benefits for sustainable development, with increased employment, avoiding health impacts from air pollution, reducing imports from fossil fuels, and benefits for the environment avoiding impacts on water and biodiversity and reducing climate change damages (Climate Analytics, 2019).

To minimise the effect of COVID-19 on the economy, the Indian government has earmarked at least USD 325bn to fund the recovery measures (Garg, Schmidt, & Beaton, 2021).This corresponds to approximately 11% of GDP in 2019. India’s overall COVID recovery stimulus package mainly supports activities related to the industries likely to have high toll on the environment, such as increasing fossil fuel use. Its most recent stimulus measures are more climate-friendly, with two-thirds of the package as India announced roughly USD 3bn in battery development and solar PV, though support for coal and gas initiatives remains (Vivid Economics, 2021), undermining a green recovery.

India has strategic opportunities for economic recovery in the area of clean transport by enhancing public transport, expanding non-motorised transport infrastructure, faster adoption of electric vehicle and making India an export hub of electric vehicle (NITI Aayog, 2020). Together, such measures could save a cumulative 1.7 GtCO2 by 2030.

In the power sector, major opportunities of green recovery include a more efficient power sector, with improved electricity distribution, enabling renewables and distributed energy resources, local manufacturing of renewable energy, and energy storage technologies (NITI Aayog, 2020).

Energy supply

Coal

There is significant uncertainty over the future of coal power capacity in India. In the recent Third Biennial Report to the UNFCCC, India highlighted its desire to continue with coal, citing its need for development growth and energy security (MoEFCC, 2021). Coal capacity is projected to increase from 202GW in 2021 to 266GW by 2029-30 (CEA, 2020). However, the National Electricity Plan 2018 includes a timeline of retiring coal power plants older than 25 years in two phases, and there are plans to reduce around 48 GW of coal capacity between 2017 and 2027 (CEA, 2018) .

While India has been reducing its share of global coal power development, it remains the second largest coal pipeline globally, behind China (Montrone, Ohlendorf, & Chandra, 2021), and has over 200 GW of coal-fired capacity in operation (a share of 11% of global capacity). The CEA projects this will increase to almost 266 GW over the next few years (CEA, 2020). However, given the number of coal projects in the pipeline, this could potentially increase by up to 300 GW (Global Energy Monitor, 2020). This increase is despite a shrinkage of India’s coal fleet by 0.3GW and the cancelling or shelving 573 GW of coal-fired power projects between 2010 and June 2018 (Global Energy Monitor, 2021).

Expectedly, this planned increase is not consistent with the Paris Agreement. To produce a Paris Agreement compatible pathway, India’s coal power generation would need to decrease immediately to a share of 5-10% by 2030 and be phased out before 2040 assuming that India is supported to do so (Climate Action Tracker, 2020a).

Coal power share in total electricity generation

There is a significant risk that India’s coal assets will be stranded, especially when considering that two thirds of India's coal-fired power plants were built in the last 10 years (Malik et al., 2020; Montrone et al., 2021), which may cause further economic fallout in a post-COVID recovery phase. The coal-fired power sector in India accounts for a significant financial loss due to the falling price of solar and wind. Project cancellations are coming faster in the face of a lack of financial viability and the increase in low-cost renewable capacity installations (Buckley & Shah, 2018). The COVID-19 pandemic is set to further weaken the already strained health of the power sector (Kanitkar, 2020a).

The pandemic induced stress is likely to exacerbate the issue of low utilisation rates of coal power plants, impacting their profitability and threatening to compound the already perilous financial position of distribution companies (Dubash, Kale, & Bharvirkar, 2018; Kanitkar, 2020b) Other drivers of stranding risk include coal shortages, water scarcity and air pollution regulation (Worrall, Roberts, Viswanathan, & Beaton, 2019).

India’s coal production is increasing and is on track to produce a record high 700 Mt of coal in 2020/21 (The Economic Times, 2020). In a move to create a privatised, commercial coal sector in India, 40 new coalfields in some of India’s most ecologically-sensitive forests are to be opened up for commercial mining (Ellis-Petersen, 2020). At the same time, thermal coal imports increased by 12.6% in 2019-20 (198 MT), contributing to the import bill by approximately INR 1.25tn (USD 17bn) (Varadhan, 2020; Verma, 2020).

In India, subsidies are available for both fossil fuels and renewable energy in the form of direct subsidy, fiscal incentives, price regulation and other government support. While coal subsidies have been largely unchanged since 2017, they are still approximately 35% higher than subsidies for renewables (Garg et al., 2020). Coal-fired power generation receives indirect financial support from the government through an exemption from income tax and land acquisition at a preferential rate (Garg et al., 2017).

A tax on coal (“coal cess”) was introduced in 2010-11, when the government set up the National Clean Energy Fund (NCEF) to provide financial support to the clean energy initiatives and technologies. However, the purpose of the NCEF has changed over time. Since 2017, this fund has been used to support losses incurred by states due to the introduction of a Goods and Services Tax (Climate Transperancy, 2019).

Natural Gas

The National Electricity Plan assumes that, while 0.4 GW of additional gas capacity will be added in the period 2017–2022 to “support grid balancing with increased share of renewables”, which will increase the risk of lock-in of the investment. NEP also proposed that no additional gas-fired power plants will be commissioned after 2022, as the availability of gas is uncertain in India (CEA, 2018).

In line with that, in its 2029-30 projection, CEA has kept India’s gas capacity at the level of its 2020 level of around 25 GW (CEA, 2020). However, the import of piped natural gas and LNG is being encouraged (Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, 2020), and four LNG terminals across the west coast (3) and east coast (1) have been commissioned. The government has taken initiatives towards developing a nationwide grid for the transportation of natural gas (Petroleum and Natural gas Regulatory Board, 2015).

Renewables

India’s commitment to the expansion of renewable energy has not been affected by the economic contraction due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Installed capacity of renewables has increased to 98.8 GW in July 2021, up from 39 GW in 2015 (CEA, 2021a) . This includes 41 GW of solar and 39 GW of wind energy, with net capacity additions of 12.4 GW of solar and 3.2 GW of onshore wind between 2019 and 2021(CEA, 2019, 2021a).

There is also a significant renewable energy pipeline. While positive, these developments are likely not sufficient to reach the country’s 2022 renewable energy target of 175GW. The government has a 2030 target of 450GW (IEA, 2020a). Our current policy emissions projection covers a range of possibilities of India coming close to - or exceeding - that target.

In past seven years India has invested INR 5.2tn (USD 70bn) in renewable energy. While investment in fossil fuel industry dropped by 4% between 2015-19, it still receives up to INR 245 trillion (USD 3.3 trillion) (Jayashree Nandi, 2021; PTI, 2021).This is an important development, as the Paris Agreement implies the need for a major shift in investments. According to the IEA, reaching net zero emissions by 2050 will require annual global clean energy investment to more than triple by 2030, to around USD 4tn (IEA, 2021b)

Solar and wind have become the lowest-cost electricity sources in India, even without a subsidy. Large-scale auctions have contributed to swift renewable energy development at rapidly decreasing prices (Schlissel & Woods, 2019). The solar tariff has declined by 17% annually between 2016 to 2019 (from USD 0.0786/kWh to USD 0.0447/kWh), mainly because of falling capital costs (IRENA, 2020). This solar tariff is 20% cheaper than the National Thermal Power Corporation Ltd. (NTPC)-generated coal-fired power tariff (Bhushan, 2017). The tariff dropped to an all-time low of INR 1.99/kWh (USD 0.027/kWh) in November 2020 (Bhaskar, 2020).

Wind power is supported via a Generation Based Incentive, while state-level feed-in tariffs apply for all renewables. Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) are in place that promote renewable energy and facilitate Renewable Purchase Obligations (RPOs), which legally mandate a percentage of electricity to be produced from renewable energy sources. The National Tariff Policy was amended in January 2011 to prescribe solar-specific RPO be increased from a minimum of 0.25% in 2012 to 3% by 2022.

Competitive bidding is also used to promote wind power projects but has faced setbacks as the Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI) cancelled 2 GW of wind tenders and reduced the upcoming tranche of bidding to 1.2 GW from the original proposal of 2.5 GW (Chatterjee, 2018). In May 2018, the Indian government announced a National Wind-Solar Hybrid Policy to promote large grid-connected wind-solar photovoltaic (PV) hybrid systems as well as new technologies and methods for combining wind and solar (Economic Times India, 2018).

The government is urging states to provide incentives for setting up designated manufacturing hubs for renewable energy in India and is providing support for renewable energy stressing the “must-run” status of wind and solar projects and extending the timelines for renewable energy projects affected by the lockdown (Mohanty, 2020).

Although installed capacity of renewables have increased to 98.8GW in July 2021 from 39GW in 2015 (Central Electricity Authority, 2021), coal-based power generation has still been increasing, at an annual average rate of 6% since 2015 (Central Electricity Authority, 2020a). On a Paris Agreement consistent pathway, emissions intensity needs to - and can - be reduced much more drastically, with a fully decarbonised electricity generation by 2050 (Climate Action Tracker, 2020a).

Industry

The main instrument to increase energy efficiency in industry is the Perform, Achieve and Trade (PAT) Mechanism, which is implemented under the 'National Mission on Enhanced Energy Efficiency’. PAT resembles an emissions trading scheme (ETS) and has been in place since 2012. PAT differs from traditional cap-and-trade systems as it sets intensity-based energy targets.

Installations that exceed their targets can sell Energy Saving Certificates to installations that did not meet their target (EDF, CDC Climat Research, & IETA, 2015). The first cycle of the PAT scheme resulted in savings of 5.6 GW and 31 MtCO2e between 2012 and 2015 (BEE, 2018). The second cycle of PAT (2016-17 to 2018-19) resulted in total savings of approximately 61.34 MtCO2e emissions, resulting in savings of INR 800bn. Other energy efficiency initiatives in the Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSME) sector have led to total avoided emissions of 0.124 MtCO2 in 2018-19 (MoEFCC, 2021).

In addition to the PAT mechanism, India seeks to launch a pilot carbon market mechanism for micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) and the waste sector. These sectors have been chosen because they are not covered by existing climate policies and currently rely on outdated technologies, meaning they have a large emissions reduction potential. COVID-19 has severely impacted these small industries. India’s November 2020 package extends USD 35bn support increased production, and to attract investments in SMEs (Vivid Economics, 2021).

India is driving forward the ‘Leadership Group for Industry Transition’, a group including other countries such as Sweden, Argentina, France and Germany, and companies, which aims to engage in an ambitious public-private effort to ensure that heavy industries meet the goals of the Paris Agreement (Kosolapova, 2019). It remains to be seen whether this will facilitate India’s low carbon transition in the industry sector. Key needs in the cement sector, for instance, include clinker substitution to facilitate decarbonisation of the cement sector (Biswas, Ganesan, & Ghosh, 2019).

Transport

Research suggests that up to 1.7GtCO2e can be avoided by 2030 if India adopts greener policies in its passenger and freight transport sectors (NITI Aayog, 2020). India has a target of a 30% share of electric vehicles (EV) in new sales for 2030 (Clean Energy Ministerial, 2019). The government is working on plans to require all two-wheelers to be electric by 2026 (Carpenter, 2019). According to a study by CEEW-Centre for Energy Finance, the Indian EV market will grow at a compounded annual rate of 36% until 2026 (Bhardwaj, 2021). To be compatible with the Paris Agreement, the share of EV sales (including two and three wheelers) needs to be between 80-95% by 2030, and 100% by 2040 (Climate Action Tracker, 2020b).

The Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Electric Vehicles in India (FAME) scheme is a key component of India’s EV strategy. It came into effect in April 2019, with financial support of INR 100bn (USD 1.35bn) to provide incentives to purchase electric vehicles, while also including provisions to ensure adequate charging infrastructure (Business Today, 2019). These incentives include subsidies to reduce the upfront cost of electric vehicles, along with other incentives such as tax concessions (Ministry of Road Transport and Highways, 2018). The Ministry of Power aims to ensure that there is at least one charging station available in a grid of 3 km2, and ensure that the electricity tariffs paid by EV owners and charging station operators is affordable (Ministry of Power, 2019). This scheme has been further extended for two more years until 2024 as it has fallen behind its targets, and only a fraction of the intended number of EVs have been sold under the programme so far (Chaliawala, 2021).

Several national programmes, including the National Urban Transport policy and the Smart Cities Mission, have been established to reduce vehicle traffic and increase transport efficiency. Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been significant changes in the urban mobility trends observed in India. People are shifting to private vehicles and the lower income group is opting for two-wheelers. Usage of non-motorised modes of transport such as cycle and rickshaw has also increased (TERI, 2020).

Bharat Stage (BS) IV standards (based on Euro IV) were applied to all new vehicles nationwide in April 2017. BS VI standards (based on Euro VI) standards, which have been applied since April 2020, establish an important precedent for leapfrogging from Euro IV-equivalent directly to Euro VI-equivalent standards (DieselNet, 2021). BS VI is applicable to all vehicles with a Gross Vehicle Weight (GVW) of more than 3,500 kg, including commercial trucks, buses and on-road vocational vehicles such as refuse haulers and cement mixers.

The Indian government has advanced different targets and policy frameworks to introduce alternative fuels in the transport sector to reduce emissions. Blending of 20% ethanol in petrol is part of such an initiative, for which the target year was slashed to 2025 from the earlier target of 2030 (NITI Aayog, 2021). Similarly, hydrogen is also seen as a potential clean energy source for the transport sector, with hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles (Kukreti, 2021). India has laid out a detailed plan for energy storage systems for increased grid integration of renewable energy, and in that context, fuel cells play an important role (NITI Aayog, 2019).

In July 2020, India railways announced plans to achieve net zero emissions by 2030. This follows a target to achieve complete electrification of its network by 2023 (Cuenca, 2020).

Agriculture

Given that well over half of India’s population generates an income from agriculture, this sector is particularly important. It is also intricately linked to the power sector, as electricity is used for water pumping in modern irrigation. The heavily-subsidised power supply to agriculture in India has contributed to the use of inefficient pumps and a resulting excessive use of both water and power (Sagebiel, Kimmich, Müller, Hanisch, & Gilani, 2015).

The agricultural sector constitutes around 18.5% of India’s total energy consumption (Gütschow, J.; Günther, A.; Jeffery, L.; Gieseke, 2021). The total power consumption in the sector is expected to rise by an estimated 54% between 2015 and 2022. Demand Side Management (DSM) has been recognised as one of the major interventions to achieve energy efficiency in India’s agricultural sector (MoEFCC, 2021).

Improvement of water use efficiency has resulted in an emissions reduction of 12 MtCO2 during the period 2017-18 to 2018-19 (MoEFCC, 2021). A recent initiative, the PM-KUSUM (Pradhan Mantri Kisan Urja Suraksha evam Utthan Mahabhiyan) scheme aims at setting up 10 GW decentralised grid-connected solar capacity in barren land, along with 17.5 million solar pumps to reduce use of diesel in agricultural activity (MNRE, 2020). This scheme will result in savings of 27 MtCO2 emissions per annum (MoEFCC, 2021).

Urea use as a chemical fertiliser is one of the main sources of agricultural N2O emissions. When urea is coated with neem, it has a higher use efficiency and slows the release of nitrogen due to inhibition of the nitrification process in soil compared to prilled urea. Since 2016 all urea in India, both imported and indigenously produced, is neem coated, which helped avoid emissions of 7.5 MtCO2 between 2017-18 and 2018-19 (MoEFCC, 2021).

India’s National Bank for Agriculture and Development (NABARD) also has a number of initiatives facilitating climate change mitigation and adaptation, e.g. by educating farmers on the impacts of climate change. Programmes such as Rural Infrastructure Development Fund and the bank’s Infrastructure Development Assistance support, in part, projects with emission reduction potential including through biogas digesters, rural energy management, renewable energy, and improving energy efficiency (NABARD, 2019).

The National Mission for Sustainable Agriculture (NMSA), adopted in 2012, seeks to climate-proof and reduce emissions in the agriculture sector, but is falling behind on implementation of planned schemes. The government has not been able to spend a large portion of the funding allocated to the Mission’s various components (e.g. soil health management, increasing tree cover, and enhancing productivity of crops) (Rattani et al., 2018).

Forestry

The Indian Ministry of Environment Forest and Climate Change has recently released the draft National Forest Policy (in November 2019) for Cabinet to make a final decision on (Kukreti, 2019). However, this decision had not yet been made, as of July 2021. The draft calls for a minimum of one-third of India’s total geographical area to be under forest or tree cover and supports the NDC target of creating an additional (cumulative) carbon sink of 2.5–3 GtCO2e by 2030. The policy is set to guide forest management in India for the next 25 to 30 years. Corresponding regulation and rules will be amended or developed going forward.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter