Policies & action

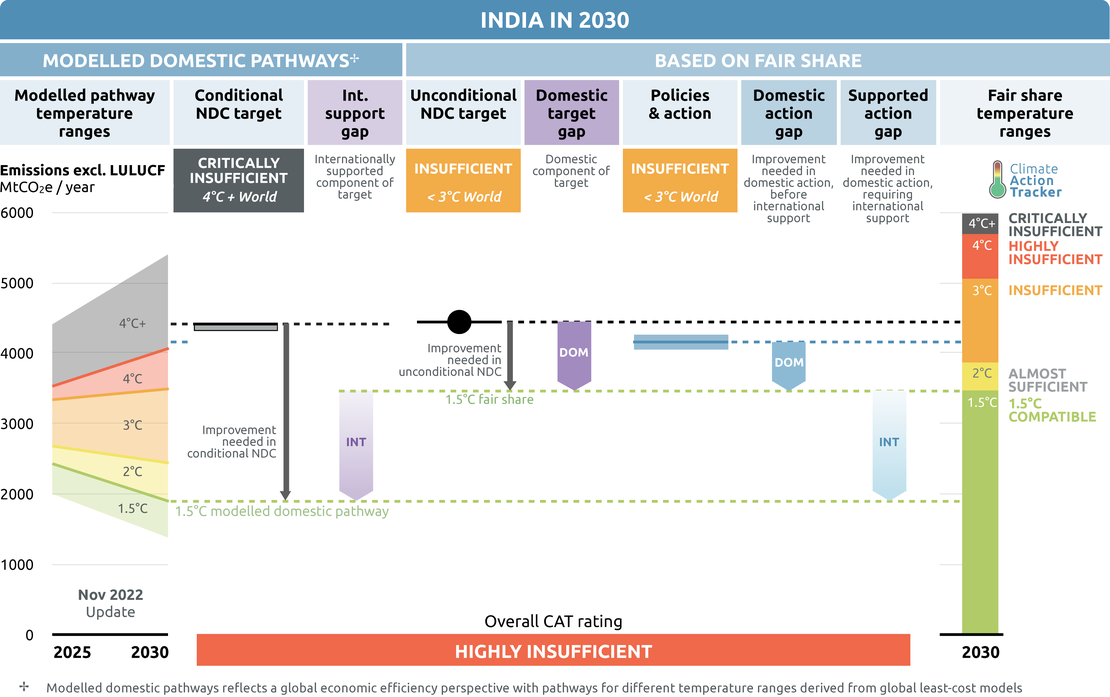

CAT rates India’s current policies and action as “Insufficient” when compared to its fair share contribution. The “Insufficient” rating indicates that India’s climate policies and action in 2030 need substantial improvements to be consistent with the 1.5°C temperature limit. If all countries were to follow India’s approach, warming would reach over 2°C and up to 3°C.

India’s current policies are not in line with its fair share contribution. India will need to implement additional policies with its own resources but will also need international support to implement policies for 1.5°C compatibility.

Further information on how the CAT rates countries (against modelled domestic pathways and fair share) can be found here

Policy overview

The CAT estimates that India’s emissions will be around 4.1-4.3 GtCO2e in 2030 under current policies. This estimate is 219-234 MtCO2e higher than our assessment last year, largely due to the faster rebound and higher historical emissions, but the projected growth rate of emissions between today and 2030 is less than last year’s assessment.

The Indian economy has started to bounce back from its COVID-19 lows, resulting in increased energy demand, particularly in the industrial sector. The impact of COVID-19 on emissions was not as deep as we had anticipated, with total GHG emissions in 2021 exceeding pre-pandemic levels.

At COP26, as part of the Glasgow Climate Pact, India supported the weakening of the final agreement to a coal “phase down” not “phase out” (Reuters, 2021). However, India’s policy direction towards achieving this is still unclear. On the one hand India is considering a proposal to halt construction of new coal-based power units, on the other hand the government is continuing its support for coal in various forms (Financial Express, 2021; Shah, 2022a).

The government is also planning to increase the share of fossil gas in the primary energy mix when 1.5°C compatible pathways for India require the phase out of fossil gas from the primary energy mix by 2050 (Climate Action Tracker, 2022).

In terms of recent developments on cross-sectoral policies, India has adopted a green hydrogen policy to scale up the green hydrogen production and increase the use of green hydrogen in industries. The government is providing policy push to improve energy efficiency in industries, building and transport sector by amending the Energy Conservation Act. The Ministry of Power has released the draft National Electricity Plan (NEP2022) highlighting its ambitious plan for renewables along with continuous capacity addition for coal. Further details of these policy developments are discussed in the section below.

Sectoral pledges

In Glasgow, a number of sectoral initiatives were launched to accelerate climate action. At most, these initiatives may close the 2030 emissions gap by around 9% - or 2.2 GtCO2e, though assessing what is new and what is already covered by existing NDC targets is challenging.

For methane, signatories agreed to cut emissions in all sectors by 30% globally over the next decade. The coal exit initiative seeks to transition away from unabated coal power by the 2030s or 2040s and to cease building new coal plants. Signatories of the 100% EVs declaration agreed that 100% of new car and van sales in 2040 should be electric vehicles, 2035 for leading markets. On forests, leaders agreed “to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030”. The Beyond Oil & Gas Alliance (BOGA) seeks to facilitate a managed phase out of oil and gas production.

NDCs should be updated to include these sectoral initiatives, if they aren’t already covered by existing NDC targets. As with all targets, implementation of the necessary policies and measures is critical to ensuring that these sectoral objectives are actually achieved.

| INDIA | Signed? | Included in NDC? | Taking action to achieve? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methane | No | N/A | N/A |

| Coal Exit | No | N/A | N/A |

| Electric vehicles | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

| Forestry | No | Yes | Yes |

| Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance | No | N/A | N/A |

- Methane pledge: India has not signed the Global Methane Pledge. Around 15% of its GHG emissions are from methane, primarily from the agriculture and waste sectors. If India were to adopt the global methane of a 30% reduction from 2020 level, this would cut emissions by about 150 MtCO2e from its 2020 level of methane emissions by 2030 and around 180 MtCO2e reduction from what it would be under current policies in 2030.

- Coal exit: India has not committed to phasing out coal. It is projected that share of coal in power mix will be 28% in 2030, down from its current share of 52%. To be 1.5°C compatible, India's coal power generation would need to reduce significantly by 2030 and be phased out by around 2040. A major opportunity exists for India to take advantage of the falling cost of solar and accelerate the exit of coal and scaling up of renewable energy. This would benefit the Indian economy with job creation and improved health.

- 100% EVs: At COP26, India signed the 100% EV declaration with a focus on two and three-wheeler auto-rickshaws. The government is working on plans to require all two-wheelers to be electric by 2026, much sooner than the COP26 timeline. Two and three-wheelers are the fastest-growing mode of transport in India in terms of sales.

- Forestry: India had committed to increasing the size of its land sink by 2.5-3 GtCO2e as part of its first NDC targets by creating additional forest cover and did not strengthen this goal as part of its NDC update this year. But between 2019 and 2021 forest cover has only increased by 0.2%. Forest area in the country has been increasingly diverted for non-forestry purposes in the last three years, mainly for the mining activity, road construction and irrigation.

- Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance: This alliance was created with the aim to restrict any kind of fossil fuel expansion by ending licensing of new projects and phasing out existing oil and gas projects. India has not joined this alliance. India has a high import dependency on both oil and gas, and domestic production of both oil and gas is insignificant. India has a target to end all kind of energy imports by 2047. Previously, in 2015, India had set a target of reducing crude oil import by 10% by 2022. This target is far from being met and the country’s import dependency has only increased. Also, recently India has announced to increase use of fossil gas in energy mix. India also planning to increase its investment in overseas oilfields in Russia and Brazil.

Energy supply

Coal

Coal power

The Indian government does not provide a clear direction on decreasing coal in the electricity sector. Under the Glasgow Climate Pact from COP26 India signed a commitment to phase down coal. An expert committee has been appointed by the Ministry of Power to develop a plan to stop building any new coal capacity in India after 2030 (Shah, 2022a). But in the recently-released draft National Electricity Plan (NEP2022) the government projects an increase in coal capacity by 18% between 2031-32 and 2021-22. This would result in a 40% increase in coal consumption between 2021-22 and 2031-32.

NEP2022 scheduled a retirement plan for 4.6 GW of coal capacity between 2022 and 2027. NEP2018 also scheduled the retirement of 22.7 GW of coal capacity and only 33% was actually realised.

While India has been reducing its share of global coal power development, it remains the second largest coal pipeline globally, behind China (Behl, 2022). India has over 200 GW of coal-fired capacity in operation (a share of 11% of global capacity), 32 GW under construction and 25 GW of announced and permitted projects, similar coal capacity addition is also projected in NEP2022 (Global Energy Monitor, 2022a; Ministry of Power, 2022c). These plans stand not only in conflict with the Glasgow Climate Pact but also with the shrinkage of India’s coal fleet and the cancelling or shelving 586 GW of coal-fired power projects between 2010 and June 2022 (Global Energy Monitor, 2022a).

The planned increase is also inconsistent with the 1.5°C temperature limit. To be 1.5°C compatible, India's coal power generation would need to reduce significantly by 2030 and be phased out by around 2040 assuming that India will receive international support to do so (Climate Action Tracker, 2020).

In this context it is important to mention that access to modern energy in India is challenging. According to government records, 96% of Indian household are now connected to the grid but there’s caveats in the definition of electrification (Agrawal et al., 2020). Also, stability of the electricity supply and affordability of modern energy are an important concern for many parts of India.

Coal power share in total electricity generation

There is a significant risk that India’s coal infrastructure will become stranded assets, especially when considering that two thirds of India's coal-fired power plants were built in the last 10 years (Malik et al., 2020; Montrone et al., 2021). The coal-fired power producers and distribution companies in India are facing a significant financial loss due to the falling price of solar and wind. Project cancellations are coming faster in the face of a lack of financial viability and the increase in low-cost renewable capacity installations(Buckley & Shah, 2018; Business Standard News, 2021).

The IEA projects that under the “stated policies scenario” coal demand in India could increase by around 30% by 2030, while some of the increase comes from power generation, it is largely driven by industrial use (IEA, 2021b).

Coal supply

In the past few years, extreme heat has pushed electricity demand to record highs, causing severe power outages, as coal stock reached a critical level in most power plants (The Financial Express, 2022a). Several studies have shown that mounting debts are a major problem in the power sector and have also contributed to this crisis (Das, 2022). However, to weather this crisis, the Indian government increased domestic production and imports of coal (Baruah, 2022; Varadhan, 2022).

India’s coal production is increasing and is on track to produce a record high 778 Mt of coal in 2021-22 compared to 716 Mt in 2020-21 (Ministry of Coal, 2022). In a move to create a privatised, commercial coal sector in India, 40 new coalfields in some of India’s most ecologically-sensitive forests will be opened up for commercial mining (Ellis-Petersen, 2020). At the same time, thermal coal imports increased by 7% in 2022 compared to 2021and expected to increase by 3% by 2023 (Times of India, 2022c).

Taxes and subsidies

In India, subsidies are available for both fossil fuels and renewable energy in the form of direct subsidies, fiscal incentives, price regulation and other government support, but subsidies for fossil fuels are nine times higher than renewables (IISD, 2022). While coal subsidies have been largely unchanged since 2017, they are still approximately 35% higher than subsidies for renewables (V. Garg et al., 2020). Coal-fired power generation receives indirect financial support from the government through an exemption from income tax and land acquisition at a preferential rate (V. Garg et al., 2017).

A tax on coal (“coal cess”) was introduced in 2010-11, when the government set up the National Clean Energy Fund (NCEF) to provide financial support to the clean energy initiatives and technologies. However, the purpose of the NCEF has changed over time. Since 2017, this fund has been used to support losses incurred by states due to the introduction of a Goods and Services Tax (Climate Transperancy, 2019).

Natural Gas

Gas is a fossil fuel and not a viable ‘bridge’ for the energy transition. Yet, the Indian government has announced that it plans to increase its share of gas consumption, and transform the country into a “gas-based economy”. It has set a target to increase the share of gas in its energy mix from 6% in 2021 to 15% by 2030 (Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, 2021).

With the planned increase in gas consumption, India will likely need to significantly increase gas imports, as domestic production has remained stagnant (Petroleum Planning and Analysis Cell, 2021), and invest in capital-intensive gas infrastructure. This exposes India to risks such as a carbon lock-in, stranded assets, and increased energy import dependencies.

The government has taken significant initiatives to support the expected import growth through the expansion of LNG terminals and re-gasification capacity, and infrastructure development to facilitate LNG transportation (The Economic Times, 2020; Times of India, 2020). More than 18,000 km of gas pipelines are under development, double the existing network. India is further developing 67.5 MTPA of import capacity, compared to the current 47.5 MTPA in operation (Global Energy Monitor, 2022b).

Industry is the biggest consumer of fossil gas in India where, apart from being used for energy purposes, it is used as a feedstock for manufacturing fertiliser and petrochemicals. While fossil gas only accounted for 5% of industrial final energy consumption in 2020, the current policies scenario, based on IEA STEPS, shows a five-fold increase in gas use by 2050, reaching 13% of industrial final energy consumption (IEA, 2021b).

India’s fossil gas plans are not consistent with a 1.5°C world. Early this year, the CAT found that if India aligned with a 1.5°C compatible pathway, it would lead to gas import savings of USD 9-24 bn in 2030 under various price and import assumptions (Climate Action Tracker, 2022). This would result in average annual import savings of USD 5-12 bn between 2021-2030.

Renewables

In September 2022, Central Electricity Authority (CEA) released a draft version of its National Electricity Plan 2022 (NEP 2022). This plan highlights that India is planning to add considerable solar and wind capacity by 2031-32, of 333GW and 134GW, respectively. But coal will continue to play a significant role in the country’s energy mix.

The lower end of the CAT’s current policy projections for India incorporates the draft NEP for power sector emissions.

By September 2022, India had reached a cumulative installed capacity of renewables (excluding large hydro) of more than 118 GW (29% of total capacity), which has doubled since 2016 (CEA, 2022). This includes 58 GW of solar and 41GW of wind energy, with net capacity additions of 22.5 GW of solar and 3 GW of onshore wind between 2020 and 2022, implying that the pandemic has not affected India’s commitment for renewable energy expansion (CEA, 2019, 2022). India ranked third in renewable energy installations in 2021, after China and USA (REN21, 2022).

Solar and wind have become the lowest-cost electricity sources in India, even without subsidies. Large-scale auctions have contributed to swift renewable energy development at rapidly decreasing prices (Schlissel & Woods, 2019). The solar tariff has declined by around 60% between 2016 to 2021 (from USD 0.0786/kWh to USD 0.028/kWh), mainly because of falling capital costs (IRENA, 2020). Wind is the second cheapest energy source after solar with a tariff range of INR2.8-3.3/kWh (USD 0.034/kWh to USD 0.04/kWh) in 2022 (GWEC, 2022).

It is expected that the solar tariff could increase by 20% in the next year due to an increase in the goods and services tax (GST) on renewable energy equipments and a proposed customs duty of 40% on imported solar modules and 25% on solar cells from China (IEEFA, 2022a). These duties seek to protect the domestic solar module manufacturers and secure market competition from Chinese manufacturers (Shah, 2022b). However, it will remain lower than the thermal electricity tariff. And it is anticipated that increase in blending of imported coal in electricity generation will push up the thermal electricity tariff by 4.5% (Times of India, 2022b).

Wind power is supported via a Generation Based Incentive, while state-level feed-in tariffs apply for all renewables. Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) are in place that promote renewable energy and facilitate Renewable Purchase Obligations (RPOs), which legally mandate a percentage of electricity to be produced from renewable energy sources. The Ministry of Power has revised the RPO rate of 24.6% in 2023 to 43.33% in 2030. The RPO rates are for wind 0.81-6.94%, hydro 0.35-2.82% and for solar 23.44-33.57% (Business Standard News, 2022).

While as positive as the growth and future plans for renewables are, they were not sufficient to reach the country’s 2022 renewable energy target of 175 GW which the government set in 2018.

The growth is also not fast enough for 1.5°C compatibility. To be 1.5°C compatible, renewable energy should reach 55-79% by 2030, with a fully decarbonised electricity generation by 2050 (Climate Action Tracker, 2020). At COP26, India announced a 2030 target of 500 GW non-fossil capacity, which it didn’t make part of its NDC update but included in NEP2022 renewable capacity projection. According to Bloomberg, India will need USD 223bn of investment to meet its 2030 renewable capacity target (The Hindu, 2022). The CAT current policy emissions projection covers a range of possibilities, with India either slightly missing or exceeding this target.

Energy storage

Grid-scale energy storage technology will play a critical role in meeting India’s 500 GW renewable capacity target. According to NEP2022, to meet the 2031-32 peak demand India will need 70 GW of storage capacity (18.8 GW pump storage and 51.5 GW battery storage).

Along with the Renewable Purchase Obligation (RPO), India has also introduced an Energy Storage Obligation. The Energy Storage Obligation (ESO) specifies that energy storage should be set at 1% in the 2023-2024 and gradually rise to 4% by 2029-2030 of total energy consumed from solar and wind (Colthorpe, 2022).

The National Green Hydrogen Policy (more below) also envisages using green hydrogen as a storage option. Because of this policy push from government, many large corporations in India are taking interest in green hydrogen and battery manufacturing (IEEFA, 2022b). The government is also seeking to promote battery production through production-linked incentive schemes, big battery storage capacity tenders and improving the market structure to be more competitive (IEEFA, 2021).

Green hydrogen policy

In 2021, the National Hydrogen Mission was launched to meet climate targets and to turn India into a “green hydrogen hub” (Ministry of Power, 2022b). In February 2022, the Ministry of Power launched the Green Hydrogen/Green Ammonia Policy for production of hydrogen or ammonia using renewable sources of energy. The policy has set a target of five million tonnes per annum (MTPA) of green hydrogen production by 2030, more than 80% of the current hydrogen demand in the country (Koundal, 2022).

One of the main components of this policy is to waive the inter-state transmission charge for 25 years for green hydrogen producers. India’s largest oil refiner, Indian Oil Corporation, estimates that these policy measures will help to reduce the cost of green hydrogen production by 40-50% (Business Standard, 2022). According to an assessment by NITI Aayog, the adoption of green hydrogen (produced domestically) has a cumulative mitigation potential of 3.6 GtCO2 by 2050 compared to the use of grey hydrogen (Raj et al., 2022).

Industry

In 2019, industrial process emissions accounted for 8% of total emissions (excl. LULUCF) and have been increasing since 1990 at an annual rate of 4% (Gütschow et al., 2021). The industrial sector of India accounts for the largest share of total primary energy demand, at 38% in 2019, growing at an annual rate of 5% during the last 10 years. 1.5°C compatible pathways show the share of electricity in the industrial energy mix increasing between 30-31% by 2030 compared to 2019 (Climate Analytics, 2021). Electrification of industry is essential to decrease the use of fossil gas and limit the need for green hydrogen, which requires various conversion steps, leading to a much lower efficiency in the process compared to using renewable electricity directly.

Energy efficiency

The Indian government has adopted an amendment of the 2001 Energy Conservation Act in 2022, after the last amended had taken place in 2010. This act regulates energy consumption by equipment, appliances, buildings and industries. The major amendments includes:

- Obligation to use non-fossil sources of energy for industries, transport, buildings

- Carbon trading

- Energy conservation code for buildings, both commercial and residential

- Standards for vehicles and vessels

- Allotment of regulatory powers of State Electricity Regulatory Commissions

- Changes in the governing council of the Bureau of Energy Efficiency

This act mandates the use of non-fossil fuel sources for industries, such as mining, steel, cement, textile, chemicals and petrochemicals. The amendments also allow industries to buy renewable energy directly from the producers enabling renewable energy producers price certainty.

The main instrument to increase energy efficiency in India’s industry is the Perform, Achieve and Trade (PAT) Mechanism, which has been in place since 2012 and is implemented under the 'National Mission on Enhanced Energy Efficiency’. It covers 13 energy intensive sectors and nearly 25% of the energy use.

In addition to the PAT mechanism, India is planning to launch a pilot carbon market mechanism for micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) and the waste sector. These sectors have been chosen because they are not covered by existing climate policies and currently rely on outdated technologies, meaning they have a large emissions reduction potential (Ministry of Power, 2022a).

The IEA estimates that current and announced industry EE policies will result in an annual improvement of 2%, but further EE policies could bring that to 3-4% and lower direct CO2 emissions by 20% (IEA, 2021b).

Industry is the biggest consumer of fossil gas in India where, apart from being used for energy purposes, it is used as a feedstock for manufacturing fertiliser and petrochemicals. While fossil gas only accounted for 5% of industrial final energy consumption in 2020, the current policies scenario, based on IEA STEPS, shows a five-fold increase in gas use by 2050, reaching 13% of industrial final energy consumption (IEA, 2021b).

The government is planning to introduce a mandatory ‘green hydrogen purchase obligation’ for the industrial users. The Ministry of Power has already mandated a gradual increase in the use of green hydrogen by replacing fossil fuels in refineries and fertiliser plants (Verma, 2021).

The developments in hydrogen are a positive start for India but not fast enough and continued support for expansion of gas use in industries risks slowing down the transition of this sector.

1.5°C compatible pathways for India show the share of electricity in industrial energy mix to reach between 30-31% by 2030 from the 2019 level of 19% (Climate Analytics, 2021). However high industrial electricity prices in India often act as a barrier to the adoption of technologies that could enable the electrification of industries (IEA, 2020).

Transport

In 2019, transport sector consumed 17% of total primary energy and 1.5% of electricity. India’s transport sector is completely dominated by fossil fuels (96% in 2020), mostly oil (93%). 1.5°C compatible pathways which require a rapid electrification of the sector show a share of electricity in total energy mix reaching 10-60% by 2030 and 44-89% by 2050.

Several national programmes, including the National Urban Transport policy and the Smart Cities Mission, have been established to reduce vehicle traffic and increase transport efficiency. Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been significant changes in the urban mobility trends observed in India. People are shifting to private vehicles and the lower income group is opting for two-wheelers. Usage of non-motorised modes of transport such as cycle and rickshaw has also increased (TERI, 2020).

Electric vehicles

India has a target of a 30% share of electric vehicles (EV) in new sales for 2030 (Clean Energy Ministerial, 2019). At COP26, India signed the 100% EV declaration with a focus on two and three-wheeler auto-rickshaws. The government is working on plans to require all two-wheelers to be electric by 2026, much sooner than the COP26 timeline (Pnadya, 2022). According to a study by CEEW-Centre for Energy Finance, the Indian EV market will grow at a compounded annual rate of 36% until 2026 (Bhardwaj, 2021). To be compatible with 1.5°C, the share of EV sales (including two and three wheelers) needs to be between 80-95% by 2030, and 100% by 2040 (Climate Action Tracker, 2020).

The Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Electric Vehicles in India (FAME) scheme is a key component of India’s EV strategy. It came into effect in April 2019, with financial support of INR 100bn (USD 1.35bn) to provide incentives to purchase electric vehicles and support for establishing the necessary charging infrastructure (Business Today, 2019). The Ministry of Power aims to ensure that there is at least one charging station available in a 3 km2 grid, and that the electricity tariffs paid by EV owners and charging station operators is affordable (Ministry of Power, 2019). In 2021 this scheme has been extended until 2024, as it has fallen behind its targets, and only a fraction of the intended number of EVs have been sold under the programme so far (Chaliawala, 2021).

Fuel standards

India strengthened its fuel/emissions standards in April 2020, when it adopted Bharat Stage VI emissions standard for vehicle (same as Euro VI standards) (DieselNet, 2021). BS VI is applicable to all vehicles with a Gross Vehicle Weight (GVW) of more than 3,500 kg, including commercial trucks, buses and on-road vocational vehicles such as refuse haulers and cement mixers.

The Indian government has advanced different targets and policy frameworks to introduce alternative fuels in the transport sector to reduce emissions. Blending of 20% ethanol in petrol is part of such an initiative, for which the target year was slashed to 2025 from the earlier target of 2030 (NITI Aayog, 2021). Similarly, hydrogen is also seen as a potential clean energy source for the transport sector, with hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles particularly for long distances for ships and potentially trucks which cannot always be electrified (Kukreti, 2021; Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, 2021).

In contrast to these steps forward, the government is developing plans to use LNG in long-haul heavy-duty trucks and other similar automotive in its draft LNG policy 2021.

The Government has also launched a voluntary vehicle scrappage policy in April 2022 to phase out old vehicles from Indian roads (A. Garg, 2022).

Rail

In July 2020, India railways announced plans to achieve net zero emissions by 2030. This follows a target to achieve complete electrification of its network by 2023 and as of 2022 80% of its network has been electrified (The Financial Express, 2022b). Indian railway is also planning to increase use of renewable energy and will install 20 GW of solar capacity (Awasthy & Mishra, 2021). 111 MW solar capacity installation already been executed on rooftops of various stations and administrative buildings.

Buildings

As of 2021 per capita building-related emissions in India are nearly four times lower than the G20 average, reflecting low energy consumption in building sector due to lack of access to the modern appliances (CTR, 2022). But energy consumption from residential buildings in India is predicted to rise by more than eight times by 2050, hence it is of vital importance for India to develop energy-efficiency strategies focused on the residential sector (Climate Analytics, 2021).

In the last few years, space cooling has become a major source of energy demand from the urban building sector as summer temperatures increase. Governmental initiatives like the Energy Conservation Building Code (ECBC), voluntary initiatives on green building guidelines and a push for the adoption of thermal performance in building design, and construction materials can help reduce the internal heat load and lower space cooling requirements in buildings (BEE, 2021).

The Energy Conservation Act 2022 amendment has expanded the scope for the buildings sector as it now includes offices and residential buildings, with a minimum connected load of 100 kW. The amendment of Energy Conservation Act has changed ECBC to “Energy Conservation and Sustainable Building Code”, which specifies norms and standards for energy efficiency, use of renewable energy and other sustainability-related requirements for different types of buildings.

Energy Efficiency Services Limited (EESL), an initiative of the Ministry of Power, is implementing the Buildings Energy Efficiency Programme to retrofit commercial buildings in India with energy efficiency devices. This programme has delivered an estimated cumulative energy savings of 790 GWh, with avoided peak demand of 75.64 MW, cumulative emissions reduction of 0.65 MtCO2 per year and an estimated cumulative monetary savings of INR 6.8 bn in electricity bills (Ministry of Power, 2022d).

Agriculture

Agriculture is the second highest emitting sector in India after energy, contributing around 15% of total emissions (Gütschow et al., 2021). Given that well over half of India’s population generates an income from agriculture, this sector is particularly important. It is also intricately linked to the power sector, as electricity is used for water pumping in modern irrigation. The heavily-subsidised power supply to agriculture in India has contributed to the use of inefficient pumps and a resulting excessive use of both water and power (Sagebiel et al., 2015).

The agricultural sector constitutes around 6% of India’s total oil and 17.5% of electricity consumption (IEA, 2021a). The total power consumption in the sector is expected to rise by an estimated 54% between 2015 and 2022. Demand Side Management (DSM) has been recognised as one of the major interventions to achieve energy efficiency in India’s agricultural sector (MoEFCC, 2021). The PM-KUSUM (Pradhan Mantri Kisan Urja Suraksha evam Utthan Mahabhiyan) scheme aims at setting up 10 GW decentralised grid-connected solar capacity in barren land, along with 17.5 million solar pumps to reduce use of diesel in agricultural activity (MNRE, 2020).

The government has also implemented measures to reduce N2O emissions associated with fertiliser (urea) use and has programmes in place to assist farmers in reducing emissions and building resiliency (Department of Fertilizers, 2022).

The National Mission for Sustainable Agriculture (NMSA), adopted in 2012, seeks to climate-proof and reduce emissions in the agriculture sector, but is falling behind on implementation of planned schemes. India’s National Bank for Agriculture and Development (NABARD) also has a number of initiatives facilitating climate change mitigation and adaptation, e.g. by educating farmers on the impacts of climate change.

Forestry

India’s first NDC set a target of 2.5-3 GtCO2e of additional carbon sink by 2030, which was reconfirmed in its 2022 update. To achieve that target a comprehensive forest policy is essential. In 2019, a draft of a revision of National Forest Policy was released, but it has still not been adopted. This revision reiterates India’s 1988 National Forest Policy target of achieving 33% forest cover.

The National Mission for a Green India was launched in 2014 to protect, restore and enhance India’s forest cover as a response towards climate change. Under this mission, the aim is to convert 10 mha of forest and non-forest land for increasing the forest cover and to improve the quality of existing forest. It is expected to enhance carbon sequestration by about 100 MtCO2e (Ministry of Environment, 2022).

As of 2021, forest and tree cover accounts for 24.6% of India’s land mass. Between 2019-2021, India added about as much forest cover as it lost. (Ministry of Environment Forest and Climate Change, 2022). Mining, road construction and irrigation all contribute to forest cover loss. (CNBCTV18, 2022).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter