Country summary

Overview

As this year’s G20 president, Japan could be in a prime position to take a leadership role on global climate action in 2019, but unfortunately recent policy developments suggest it prefers to take a back seat. The draft long-term strategy to reach net zero emissions “as early as possible during the second half of the 21st century”, which just got adopted by the Cabinet on 11 June, 2019, is far from the ambition required to achieve the Paris Agreement’s long-term temperature goal, especially in the light of Japan’s common but differentiated responsibilities. The draft long-term strategy also shies away from committing to a complete phase-out of coal-fired power generation, even in the long term.

The Japanese government appears to have declined to co-lead with Chile on the mitigation strategy workstream for the UN Climate Summit in September 2019 (see difference between February and May reports and announcements). This is in stark contrast to what Prime Minister Shinzo Abe urged in an article for the Financial Times in September 2018 that countries need to take “more robust action” on climate change.

Japan adopted its Basic Energy Plan in July 2018, but there is no vision nor strategy on how it can go beyond its 22–24% by 2030 renewable electricity target, which is likely to be achieved with existing policies. Instead it focusses on whether new nuclear reactors could be constructed toward 2050 and how to reduce the economic costs resulting from the renewable electricity support scheme.

- Japan's coal plant construction plans, which could add a possible 15 GW of coal power, remain a major concern. We project that coal could continue to supply a third of Japan’s electricity in 2030 without a further push for renewables, This level of coal is not consistent with the findings of the IPCC Special Report on 1.5°C, which shows that coal-fired power needs to be phased out by 2050 globally to keep warming below 1.5°C with limited or no overshoot.

Japan has also been a major funder of coal-fired power plants overseas, alongside China and South Korea. While Japan’s public finance institutions haven’t changed their stance on coal, the private sector is showing a sign of change: since May 2015 several major firms in the financial sector have announced a shift away from investing in coal power plants.

One major positive policy development is in the transport sector—the Government, together with all major car manufacturing companies, is planning to set a long-term target of reducing tank-to-wheel CO2 emissions by 90% below 2010 levels by 2050 for new passenger vehicles, assuming a near 100% share of electric vehicles. Other positive developments include the proposed stricter regulations on the HFC recovery from end-of-life appliances as well as the stricter implementation of environmental impact assessment process on new coal-fired power plants. It is also worth noting that the draft long-term strategy reiterates Japan’s commitment to develop hydrogen as a major decarbonised fuel, for which a national strategy was established in 2017.

Subnational and non-state actors are also becoming increasingly active—the Japan Climate Initiative was launched in October 2018 with more than 360 member organisations as of April 2019 to accelerate the transition toward decarbonisation.

Japan will overachieve its 2020 pledge regardless of the future role of nuclear power, but might fall short of achieving its 2030 target in the NDC if no additional measures are implemented. The lower end of the range for current policy projections misses the NDC target by less than 5 MtCO2e/yr.

Japan’s future emissions are challenging to predict, owing to uncertainty around the future role of nuclear, coal and renewable energy. Nevertheless, the Government’s current energy policy could bring its NDC target within reach, highlighting the fact that it could be more ambitious. Implemented policies will lead to emissions levels of 10–15% below 1990 levels in 2030, excluding LULUCF. Under current policies, Japan will overachieve its 2020 pledge regardless of the future role of nuclear power.

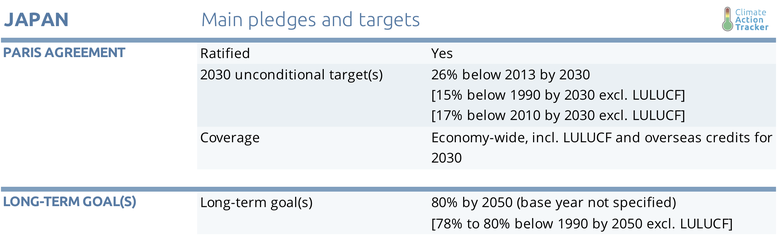

Japan’s proposed Kyoto Protocol-like accounting of sinks (land use change and forestry) in its NDC reduces its effective target by about 3% below 1990 levels, resulting in a target of 15% below 1990, excl. LULUCF. We rate the target “Highly insufficient,” meaning that if all countries were to adopt this level of ambition, global warming would likely exceed 3–4°C in the 21st century. This is in stark contrast to Japan’s claim that its NDC is in line with a pathway consistent with the Paris Agreement’s long-term temperature goal.

The 2030 electricity mix assumed in Japan’s NDC is based on the 2015 Long-Term Energy Demand and Supply Outlook that foresees 20–22% of electricity being supplied by nuclear energy, 22–24% by renewable energy and the remaining 56% by fossil fuel sources. The 2018 Basic Energy plan reiterated this target. This strategy stands in strong contrast to what would be compatible with a long-term, 1.5 °C-compatible strategy, let alone a 1.5 ℃ pathway.

Two important aspects highlight why this is the case:

First, the energy strategy foresees a relatively large share of base load power plants (i.e. nuclear and coal fired power plants) of 46–48% in 2030 of total electricity production. Decarbonisation strategies in most countries foresee a significant increase of variable renewable energy resources, which requires a paradigm shift in how energy systems are structured and managed, and will increase their complexity. Such shifts take time and require the development and rollout of new technologies such as differently designed distribution networks (see e.g. Bloomberg (2015)).

Second, in the Outlook, fossil fuel power plants would play an important role in Japan’s energy mix in 2030 (56%), with 26% of total electricity generation expected to come from coal-fired power plants. This share could increase even further as the strong public opposition to nuclear power in the wake of Fukushima brings a challenge to foreseen nuclear contribution. There have already been a few district court rulings to halt the operation of the restarted reactors (JAIF, 2018). We project that the coal share could further increase to 34% by 2030 from 32% in 2015 if the nuclear reintroduction fails without a further push for renewables.

Further on Japanese coal plants, it is uncertain whether the full 15 GW capacity currently in coal-fired power plant planning would actually be built because new coal-fired power plant constructions are becoming increasingly difficult in Japan. One reason is economic: in April 2018, J-POWER, an electric utility, cancelled its plans for two coal fired power plants due to decreasing electricity demand in the region. Stricter environmental regulation has also played its part: the mandatory environmental impact assessment (EIA) process that includes the need for consistency with the NDC, has also been a safeguard against some new coal-fired power plants. Some plants that received negative EIA results in recent years were forced to cancel (e.g. Ichihara and Soga) , while others (Taketoyo no.5 and Misumi no.2) went on to complete construction.

In March 2019, MOEJ announced three new actions towards decarbonisation of the power sector, including the stricter enforcement of EIAs. Cancellation requests would be issued to new coal-fired power plant construction plans without a justification for the need for the plant other than economic feasibility, or a clear explanation of the role the new power plant would play towards achieving the 2030 electricity mix target. Coal-fired power plants already under construction will not be affected by this action.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter