Country summary

Overview

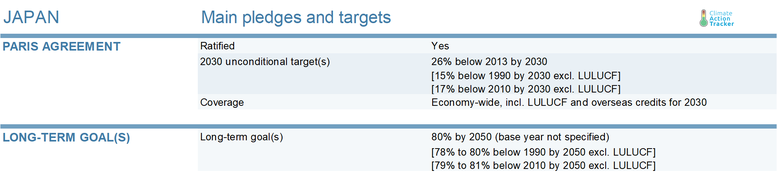

NDC update: In April 2021, Japan proposed updated NDC targets. Here is our analysis of the announcement.

The COVID-19 crisis continues to have a significant effect on Japan’s economy. The nation’s energy and industry CO2 emissions for the first six months of 2020 are estimated to have dropped by 7.5% compared to the same period in 2019. The impact of COVID-19 comes up on top of an already declining trend in GHG emissions, which dropped, on average, 2.5%/year between 2013 - 2018 and 3.9% in 2018. Together with recent announcements to phase out inefficient coal-fired power plants and boost offshore wind power, the government's current policies are projected to overachieve its "Highly insufficient" 2030 NDC target, an outcome that will still be far from the Paris Agreement-compatible transition pathways.

For the first six months of 2020, the impact of COVID-19 on CO2 emissions was estimated to be the largest in the aviation sector (-29% compared to the same period in 2019), followed by the industry (-12%) and the ground transport sector (-8%). By contrast, CO2 emissions from the electricity sector are estimated to have dropped by less than 3%. The Climate Action Tracker estimates that overall GHG emissions in 2020 will be 6‑11% lower than 2019.

The Japanese government’s implemented response measures to address COVID-19 so far include few measures that would be considered as “green recovery”. The government plans to discuss medium- to long-term “green recovery” measures during its process of revising the country’s Basic Energy Plan, its target 2030 energy mix and the new GHG reduction target; started on 1 September 2020. It plans to conclude the revision process by mid-2021. The subsequently-revised NDC is expected to be submitted before COP26 in 2021, replacing the current NDC recommunicated to the UNFCCC in March 2020.

In the context of the Basic Energy Plan revision, the Japanese government recently announced two important changes in its policy related to coal-fired power plants: one is to retire the large majority of old and inefficient plants by 2030, and the other is to restrict coal power finance overseas only to countries that are committed to long-term decarbonisation. The effectiveness of the announced policies is under scrutiny. The former does not affect the construction and operation of high-efficiency coal-fired power plants. The latter is somewhat contradictory because any country with a decarbonisation plan will not be investing in new coal plants, given the average lifetime of such plants being 46 years; this also goes against the urgent need for all regions to phase out coal by 2040. Despite the potential loopholes and limitations to the effectiveness of these policy announcements, they – together with the recent plans to boost offshore wind power deployment by installing 10 GW capacity by 2030 — may indicate a major (albeit reluctant) shift in Japan’s climate policy and that the Japanese government is at last officially acknowledging there’s no bright future for coal.

We assess that the implemented policies will lead to emissions levels of 18–29% below 1990 levels in 2030, excluding LULUCF. Our latest projections are 5% to 13% lower in 2030 compared to our previous projections in December 2019 due to the estimated long-term impact of COVID-19, the update of the GHG inventory data that showed a 4% reduction of emissions in 2018 compared to the previous year, as well as the downward revision of fossil fuel-fired power generation in 2030 following recent government announcements. Our projections also show that that Japan would meet its NDC target (15% below 1990 levels) even without the estimated impact of COVID-19 taken into account.

The CAT rates the existing Japan NDC target under the Paris Agreement “Highly Insufficient”, as it is not stringent enough to limit warming to 2°C, let alone 1.5˚C. If all countries were to follow Japan’s approach, warming could reach over 3°C and up to 4°C.

According to our analysis, Japan will meet its proposed targets with currently implemented policies. We assess that the implemented policies will lead to emissions levels of 18–29% below 1990 levels in 2030, excluding LULUCF and considering the impact of the COVID-19. This means Japan will significantly overachieve its NDC target with current policies.

Japan’s proposed Kyoto Protocol-like accounting of sinks (land use change and forestry) in its NDC reduces its effective target by about 3% below 1990 levels, resulting in a target of 15% below 1990, excl. LULUCF. We rate the target “Highly insufficient,” meaning that if all countries were to adopt this level of ambition, global warming would likely exceed 3–4oC in the 21st century. This is in stark contrast to Japan’s claim that its NDC is in line with a pathway consistent with the Paris Agreement’s long-term temperature goal.

The 2030 electricity mix assumed in Japan’s NDC is based on the 2015 Long-Term Energy Demand and Supply Outlook that foresees 20–22% of electricity being supplied by nuclear energy, 22–24% by renewable energy and the remaining 56% by fossil fuel sources. The 2018 Basic Energy plan as well as the recently adopted long-term strategy reiterated this target. These targets stand in strong contrast to what would be compatible with a long-term 2°C, let alone 1.5 °C Paris Agreement pathway. Following the recent developments on coal-fired power and offshore wind power described above, we expect Japan will introduce some substantive changes in its 2030 energy mix target in the next revision of the Basic Energy Plan which it plans to communicate by mid-2021.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter