Policies & action

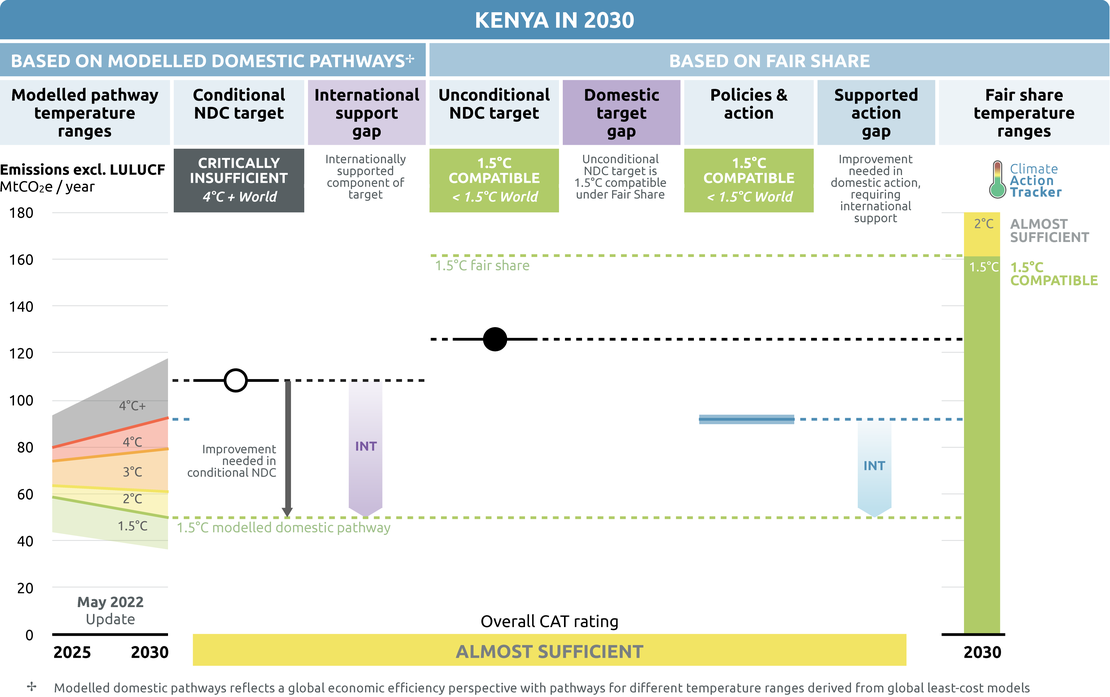

We rate Kenya’s policies and action as “1.5°C compatible” compared to its fair share. The “1.5°C compatible” rating indicates that Kenya’s climate policies and action are consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C when compared to Kenya’s fair share contribution. Kenya’s emissions still increase under our projections, and Kenya should receive international support for further mitigation action to go beyond what is necessary through its own resources.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, our projections indicated that Kenya was on track to meet, and even overachieve its NDC target of 108 MtCO2e in 2030 (excl. LULUCF). While it is challenging to project the eventual impact of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic on future emissions, the CAT estimates that Kenya’s 2030 emissions under current policy projections are around 3% to 5% below our pre COVID-19 projection.

While Kenya’s updated NDC submission does not provide sectoral mitigation targets, the NCCAP 2018-2022 includes sectoral emissions reduction targets based on the 2016 NDC, which we refer to as sectoral targets.

Although the Ministry of Energy’s latest electricity supply plan (2020-2040 LCPDP) does not include emissions scenarios, the 2017-2037 iteration projects electricity emissions to be reduced to almost zero in 2030 (Republic of Kenya, 2021c). Although the sector will partly miss its target of retiring three thermal plants by 2022, the sector is still on track to exceed its 2030 emissions reductions target.

Kenya has also published sectoral plans for reaching emission reductions targets for the transport and agriculture sectors. The Transport Sector Climate Change Annual Report(s) and Climate Smart Agriculture (CSA) Strategy focus on the implementation of the priority mitigation actions outlined in the NCCAP to ensure the sectors’ emissions reduction efforts are in line with achieving the 2030 NDC target (Government of Kenya, 2020a; Ministry of Agriculture, 2018).

Provided Kenya achieves its transport and agriculture targets and does not proceed with plans to build a new coal-fired power plant, it will overachieve its updated NDC. The pandemic puts even further downward pressure on this emissions trajectory.

Policy overview

Although climate mitigation is not prioritised in President Uhuru Kenyatta’s Big Four Agenda, nor in the country’s Vision 2030, the Kenyan Government had already adopted the Climate Change Act (2016), which provides a framework for the promotion of climate-resilient low-carbon economic development (Government of Kenya, n.d., 2020b; Republic of Kenya, 2016b).

The Act mandates the government to develop a National Climate Change Action Plan (NCCAP) and update it every five years (Republic of Kenya, 2016b). The second and most recent NCCAP covers the period 2018-2022 and its main objective is to guide climate action during that time and support the implementation of Kenya’s NDC. Under the NCCAP, sector representatives define priority mitigation actions that are designed to ensure that sectors achieve their sectoral targets (Government of Kenya, 2018).

The CAT’s current policy projections for Kenya covers a range of GHG emissions pathways.

Due to a lack of clarity around climate policies and the state of their implementation, the CAT uses the IEA Africa Energy Outlook Stated Policies Scenario and U.S. EPA projections as the upper bound of its current policy scenario.

The lower bound of the current policy projections uses the 2017 update of Kenya’s emissions baseline projections, but includes the current emissions reductions pathways and/or targets laid out in sectoral plans for the electricity, transport and agriculture sectors (see assumptions section).

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the CAT’s current policy projections for Kenya were estimated to reach emissions levels of 82 to 83 MtCO2e in 2020, excluding LULUCF. For 2030, the current policy analysis estimated emissions to be 93 to 99 MtCO2e pre-COVID, excluding LULUCF. Post-COVID, current policy projections estimate 2030 emissions to be 90 to 94 Mt MtCO2e, excluding LULUCF.

The COVID-19 pandemic and accompanying restrictions have impacted Kenya’s developing economy. The demand for Kenya's main export commodities (e.g. horticultural produce, cut flowers) declined, resulting in decreased output, but export earnings proved to recover quite quickly. Tourism is an important component of Kenya’s economy, and the sector faced a sharp decline in earnings and employment (Onsomu et al., 2021).

The pandemic has set back Kenya’s poverty reduction goals. Across 2020, poverty increased by 7% due to unemployment and a greater reliance on savings. Short-term poverty has remained above pre-pandemic levels, with rates stagnating in rural areas (World Bank Group, 2021). Recovery efforts focused on health care, social protection, and fiscal measures, while climate change-related aspects were not explicitly covered (MyGov, 2020). International sources estimate that annual GDP growth slowed to -0.3% in 2020 and rebounded to 7.2% in 2021 (IMF, 2022).

Our analysis indicates that the forestry and waste sectors are on track to meet their 2030 sectoral emissions reductions targets, provided the mitigation actions outlined in the NCCAP are implemented and integrated into public policy. Priority mitigation actions proposed for the energy demand and industrial processes sectors may be, however, insufficient to comply with their respective 2030 targets.

During the pandemic, Kenya has introduced the National Energy Efficiency and Conservation Strategy in 2020 and the Sustainable Waste Management Act in 2021. Although implementation plans are still unclear, the policies will address priority mitigation actions outlined in the NCCAP for the energy demand and waste sectors, respectively.

Sectoral pledges

In Glasgow, four sectoral initiatives were launched to accelerate climate action on methane, the coal exit, 100% EVs and forests. At most, these initiatives may close the 2030 emissions gap by around 9% - or 2.2 GtCO2e, though assessing what is new and what is already covered by existing NDC targets is challenging.

For methane, signatories agreed to cut emissions in all sectors by 30% globally over the next decade. The coal exit initiative seeks to transition away from unabated coal power by the 2030s or 2040s and to cease building new coal plants. Signatories of the 100% EVs declaration agreed that 100% of new car and van sales in 2040 should be electric vehicles, 2035 for leading markets, and on forests, leaders agreed “to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030”.

NDCs should be updated to include these sectoral initiatives, if they aren’t already covered by existing NDC targets. As with all targets, implementation of the necessary policies and measures is critical to ensuring that these sectoral objectives are actually achieved.

| KENYA | Signed? | Included in NDC? | Taking action to achieve? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methane | Intends to join | N/A | N/A (non-member) |

| Coal exit | No | No | N/A (non-member) |

| Electric vehicles | Yes | No | Not clear |

| Forestry | Yes | No | Neutral |

- Methane pledge: Kenya has not signed the methane pledge. There are reports that it intends to sign it, but has not yet approved a plan to do so (Adepoju & Fletcher, 2021). Methane makes up around half of Kenya’s total emissions. Becoming a signatory can have significant emission reductions implications for the country.

- Coal exit: Kenya has not signed the coal pledge. While Kenya has not yet deployed coal power generation, the long-term energy supply plan outlines coal as 12% of the country’s power supply by 2040 (Republic of Kenya, 2021c). While the plans to build the Lamu coal plant have been cancelled, the construction of the Kitui power plant in 2034–36 is still viable. Refer to the Energy supply (Coal) section of the policies tab for more information on coal generation in Kenya.

- 100% EVs: Kenya adopted the electric vehicle pledge at COP26. While it did not commit to the 2040 target, Kenya agreed that it will accelerate the transition to zero emissions vehicles in their market. Electric vehicles are not a significant component of the country’s National Climate Change Action Plan (NCCAP).

- Forestry: Kenya signed the forestry pledge at COP26. This is significant, given Kenya’s high share of LULUCF emissions, which made up one-third of Kenya’s total emissions on average over the last 20 years. Refer to forestry section of the policies tab for more information on actions taken in the sector.

Energy supply

Electricity supply

As of 2021, the installed grid capacity in Kenya was 2,984 MW, with the peak load reaching a record high of 2,036 MW in November (EPRA, 2021; KenGen, 2021). The energy mix in Kenya is dominated by renewable energy technologies (over 92.3% of electricity generation in 2020/2021) with geothermal and hydro accounting for 43.6% and 36.5% of electricity, respectively.

Wind power generation significantly increased from 0.3% in 2018 to 11.5% in 2020 (EPRA, 2021). This is mainly attributed to the additional wind power from Lake Turkana Wind Farm, Africa’s largest wind power project and the single largest private investment in Kenya’s history (Swedfund, 2017).

In 2018, the government announced that the country will be powered entirely by green energy by the end of 2020. This goal was not fully achieved as thermal plants still accounted for 6.5% of electricity generated in 2021 (Capital FM Kenya, 2018; EPRA, 2021). However, these announcements are in stark contrast to plans to explore the use of fossil energy resources in the future.

In Kenya, the government has the distinct ability to steer electricity generation projects, as most of the country’s energy sector institutions are either fully or partially state-owned. The Least Cost Power Development Plan (LCPDP), which is coordinated and published by the Energy and Petroleum Regulatory Authority (EPRA), is the major planning process in the electricity supply sector in Kenya and deals with capacity planning, demand projections and transmission investment requirements summarised in a 20-year rolling plan on a biennial basis (Republic of Kenya, 2018). The latest publicly available edition covers the period 2020-2040.

Our lower bound for current policy projections still uses the GHG emissions scenario from the 2017-2037 plan since the newest iteration of the LCPDP does not include an updated scenario (Republic of Kenya, 2021c).

Compared to the 2017-2037 LCPDP, the 2020-2040 plan accounts for changes in the load forecast due to the COVID-19 pandemic, changes in market dynamics that influence future power expansion, and accommodates government policy guidance on renewable energy expansion. The extent of planned coal capacity has decreased compared to the previous report. In the 2017 LCPDP, the planned capacity for coal in 2037 was 19.5% of total installed capacity, while this decreases to 12% in 2040 in the latest LCPDP (Republic of Kenya, 2018, 2021c). This indicates that new emissions scenarios for the electricity sector based on the 2020-2040 LCPDP would likely be lower than those used by the CAT in current policy projections.

In 2019, Kenya’s new Energy Act was passed into law. The Energy Act 2019 consolidates laws relating to the promotion of renewable energy (anchoring the Renewable Energy Feed-in-Tariff-System), matters related to geothermal energy, and the regulation of petroleum and coal activities, among others. The Act contains neither a target for sectoral emissions reductions nor a reference to climate mitigation (EPRA, 2019b). In 2020, EPRA published draft solar PV regulations for public review and comment, which seek to update the regulatory regime to account for developments in the sector including the maturation of the solar PV industry (EPRA, 2019a).

The government’s Finance Act 2021 reinstated the VAT exemption on clean cooking and solar energy products, further supporting access to modern energy for all (Republic of Kenya, 2021a). Initially, the bill was meant to introduce a tax on clean cooking and solar energy products. Manufacturers estimate that this tax would have reduced the growth of the clean cookstoves sector from 30% annually to 10%, causing corresponding job losses in the sector (The Standard, 2020).

Coal

Kenya has coal resources which have not been exploited thus far. To date, coal-based power generation has not been deployed in East Africa (Mpungu, 2019). The Kenyan government had plans to build the Lamu coal power plant, a 981 MW power plant to be commissioned by 2024, and a 960 MW coal-fired power plant in Kitui, which was scheduled for 2034-36 (Republic of Kenya, 2018). The most recent iteration of the LCPDP (2020-2040) still includes the Lamu and Kitui coal power plants in its long-term energy planning, although financing for Lamu has already been discontinued by the developers (Republic of Kenya, 2021c).

The implementation of the Lamu coal power plant has been embroiled in controversy and court cases and suffered many setbacks in recent years (BankTrack, 2020; Praxides, 2022). In June 2019, environmental activists scored a big win against the power plant when the Kenyan National Environment Tribunal withdrew the plant’s Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) licence. Potential funders including the African Development Bank (in 2019) and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) (in 2020) both announced that they would not finance the project, the latter citing environmental and social risks associated with the project (Save Lamu, 2020; Winning, 2019). General Electric (GE), the American conglomerate meant to design, construct, and maintain the power plant announced its intention to exit the new-build coal power market, which would include the Lamu power plant (Business Daily Africa, 2020).The Lamu power plant plans suffered their final blow when China announced in 2021 that it would stop building and financing coal-burning plants overseas, putting to rest any plans to revive discussions surrounding its inception (Sengupta & Gladstone, 2021). The future of the Kitui coal power plant is unclear.

Across Africa, existing coal power generation would need to be phased-out by 2034 to be compatible with the Paris Agreement (Yanguas Parra et al., 2019). Clearly, building new coal-fired power plants in Kenya would be inconsistent with that goal.

Any new coal fired power stations built in Kenya will be underutilised due to a lack of demand. Under the most recent 20-year power plan, the proposed Lamu coal-fired power plant will have an average capacity factor of 7%, due to its economic disadvantages compared to other planned generation options and significant downward revisions in demand projections compared to previous versions of the planning document (Republic of Kenya, 2021c). According to the 2018-2022 National Climate Change Action Plan (NCCAP), the priority mitigation action for the electricity supply sector is developing 2,405 MW of new grid-connected renewable electricity generation and retiring three thermal plants, with a total abatement potential of 9.89 MtCO2e by 2030 at a 70% completion rate (Government of Kenya, 2018).

The planned increase in grid-connected renewable electricity generation is reflected in the most recent LCPDP (Republic of Kenya, 2018, 2021c). However, the government’s plans to retire three grid-connected thermal plants (Kipevu: 120 MW in 2019; IberAfrica: 108.05 MW in 2019 and Tsavo: 74 MW in 2021) are not entirely reflected in the 2020-2040 LCPDP. So far, only the diesel fired IberAfrica 1 with a net capacity of 56 MW and the oil-fired Tsavo plant with a net capacity of 74 MW have been retired in 2019 and 2021, respectively. IberAfrica 2 (52.5 MW) is due for decommissioning in 2034. Also, the decommissioning of the oil-fired Kipevu plant is not on track, with Kipevu 1 (60 MW) and Kipevu 3 (115 MW) due in 2023 and 2031, respectively. While the former is entering its final stages of decommissioning, the construction of a new pipeline and oil terminal makes the transition to clean energy process unclear (Kwame, 2020; Mwita, 2021).

Notwithstanding the partly missed target for retiring thermal plants, the electricity sector is on track to exceed its goal to reduce emissions by 10 MtCO2e below BAU by 2030, corresponding to 22% of the overall abatement task (Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, 2017a). This is mainly due to the much lower demand projections as well as the restricted amount of generation from new coal capacity. The current pathway for electricity supply emissions under the 2017-2037 LCPDP projects emissions to decrease to 0.3 MtCO2e in 2030 compared to an anticipated increase to 44.7 MtCO2e in 2030 in the original NDC baseline (Republic of Kenya, 2018). This development would ultimately ensure that Kenya reaches or even overachieves its NDC target.

Energy demand

Energy demand is divided among three main types of energy carriers: fossil fuels, biomass and electricity. Fossil fuels and biomass are used to produce heat. Kenyans rely on the traditional use of biomass as the primary energy source for heating and cooking. Around 75% of all Kenyan households use fuelwood or charcoal for cooking, while about 93% of the rural population relies on firewood or charcoal as their primary fuel (NewClimate Institute & EED Advisory, 2021).

In 2020, the Ministry of Energy released the Kenya National Energy Efficiency and Conservation Strategy. It establishes energy efficiency targets in the buildings, industry, agriculture, transport, and power sectors to meet the goal of reducing the national energy intensity by 2.8% per year. The strategy also aims to ensure that energy efficiency measures contribute to the achievement of the NDC by keeping GHG emissions due to energy supply and consumption from 7.4 MtCO2e in 2015 to a target of 8.2 MtCO2e in 2025. The implementation status of the strategy is currently unclear and the strategy awaits the release of the corresponding Implementation Action Plan (Ministry of Energy, 2020).

The government, in partnership with stakeholders, has launched several energy efficiency and conservation initiatives. The Ministry of Energy has worked with the Kenya Association of Manufacturers (KAM) to establish a Centre for Energy Efficiency and Conservation that promotes energy efficiency in private sector companies and public institutions such as government buildings. The estimated energy savings from the programme in 2020 were equivalent to running the 230 MW hydroelectric Gitaru Power Station for one year (Ministry of Energy, 2020). The Ministry of Energy has further implemented improved cookstoves programmes and developed regulations that influence the uptake of climate-related technologies, such as solar water heating, solar PV systems and cookstoves. Kenya Power, a national electric utility company, has implemented a programme to distribute compact fluorescent lights (Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, 2017b).

EPRA has developed updated energy management regulations which are still going through the bureaucratic approval process. The Draft Energy Management Regulations 2020 propose changes for energy audits by, inter alia, suggesting the introduction of accredited Energy Service Companies (ESCO) and energy savings certification which can be traded under the Energy Act 2019 (EPRA, 2020).

The priority mitigation actions for the energy demand subsector are related to the development and distribution of improved biomass (charcoal and biomass) and clean energy (LPG, biogas and ethanol) stoves with a total abatement potential of 7.64 MtCO2e by 2030 (Government of Kenya, 2018). The sector’s target is to reduce emissions by 6.5 MtCO2e by 2030, corresponding to 14% of the overall abatement task (Government of Kenya, 2018).

The uptake of clean biomass and clean cooking is low compared to what needs to be achieved for the NCCAP target. As of June 2020, only 280 households had adopted clean cookstoves relative to the four million households outlined in the target (Ministry of Environment and Forestry, 2021a).

Industry

Industrial processes

Kenya’s industrial sector is the largest in the Eastern African region, underscoring the importance of the sector to the economy of Kenya and neighbouring countries. In 2020, the industrial sector contributed 17% to Kenya’s GDP, the third-largest after agriculture and services (Statista, 2022). Industrial process emissions in Kenya are dominated by the cement and charcoal manufacturing industries (Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, 2017b). The manufacture of cement is identified as a core industrial sector, with a growing demand for cement from within Kenya and from neighbouring countries. Charcoal production uses mainly traditional inefficient technologies and the sector remains largely informal (Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, 2017b).

The only priority mitigation action for the industrial processes sector indicated in the NCCAP 2018-2022 relates to the implementation of the Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Action (NAMA) for Kenya’s charcoal sector with an abatement potential of 1.2 MtCO2e by 2030 (Government of Kenya, 2018). Cement manufacturers have been shifting to coal to reduce costs, making the sector a significant potential consumer of domestic coal if Kenya begins to mine its own reserves. This development wipes out the potential for reducing emissions through energy efficiency improvements in the cement sector, which was previously estimated at 0.23 MtCO2e. This action has therefore not been prioritised in the NCCAP 2018-2022 (Government of Kenya, 2018).

According to the original NDC baseline, absolute emissions from the industrial processes sector are projected to grow from 3.3 MtCO2e in 2015 to 5.9 MtCO2e in 2030 while the contribution of industrial process emissions to total national emissions is expected to roughly remain at 6% (excl. LULUCF) (Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, 2017a). Under the current lower bound policy projections, absolute emissions are projected to grow to 6.7 MtCO2e in 2030 (Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, 2017a).

The sector’s target is to reduce emissions by 0.8 MtCO2e by 2030, corresponding to 2% of the original overall emissions reduction target of 30% by 2030 (Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, 2017b).

Transport

Kenya has experienced high rates of urbanisation and development, but transport systems and infrastructure development have not kept pace. Traffic conditions in Nairobi and other major cities are characterised by congested and unsafe roadways that contribute to local air pollution and significant economic losses (Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, 2017b).

Four priority mitigation actions were identified by sector experts in the NCCAP 2018-2022. The option with the largest mitigation potential is the implementation of the Mass Rapid Transport System for Greater Nairobi with an abatement potential of 2.47 MtCO2e. Construction is underway for one bus corridor and a pilot bus service is expected to commence in June 2022, while another line out of the planned five will start construction in 2023 (NAMATA, 2022). As of 2020, the construction of the commuter rail stations was substantially completed and 30% of existing tracks have been rehabilitated (Government of Kenya, 2020a).

The other mitigation options include a transfer of freight from road to rail between Nairobi and Mombasa (1.18 MtCO2e), improvement of the heavy-duty truck efficiency (1.04 MtCO2e) and the electrification of the SGR line between Nairobi and Mombasa, which is currently run by diesel rail cars (0.34 MtCO2e) (Government of Kenya, 2018). The assumption behind the above-mentioned abatement potentials is that Kenya’s electricity mix was to remain dominated by renewable energy technologies, such as geothermal or hydropower.

All priority mitigation actions together have an abatement potential of 5.04 MtCO2e, against a sectoral target of 3.7 MtCO2e (Government of Kenya, 2018).

The implementation of the NCCAP 2018-2022 transport mitigation actions is on track. As of June 2020, over 33 km of non-motorised transport facilities (e.g. pedestrian and bike paths) have been built, corresponding to 22% of the NCCAP target. Over 4.6 Mt of freight of Mombasa to Nairobi shifted from road to rail, representing 17% of the target (Ministry of Environment and Forestry, 2021a).

The transport sector, with support from GIZ, was the first and so far the only sector to meet the regular reporting and progress tracking requirements of the Climate Change Act (Government of Kenya, 2019). This collaboration, however, ended in 2021. It is unclear whether the reporting and progress tracking will continue for the sector.

Absolute emissions in the transport sector are projected to grow from 11.4 MtCO2e in 2015 to 23.4 MtCO2e in 2030 according to the baseline scenario. This is mainly attributed to an increase in the number of passenger and freight vehicles on the road. To meet the sectoral emissions target, 2030 emissions from the transport sector should not exceed 17.54 MtCO2e (Government of Kenya, 2020a; Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, 2017b).

If the sector successfully implements the measures from the NCCAP 2018-2022 and the sector’s Climate Change Annual Report, it is likely that the sectoral target can be met.

Buildings

Buildings represented around 67% of Kenya's total final energy consumption in 2019. This high value is mainly attributed to the reliance of biomass for residential cooking, where biomass accounted for 64% of total energy supply. Electricity consumption, meanwhile, only accounts for around 4% of energy use, with buildings using 47% of electricity generation capacity. About 33% of electricity use is attributed to residential buildings, while 15% is attributed to commercial and public buildings (IEA, 2022).

Around 75% of Kenyan households use wood fuel as their primary cooking fuel. Residential cooking fuels accounted for an estimated 24.8 MtCO2e of GHG emissions, or around a quarter of Kenya’s total emissions, and resulted in 21,500 premature deaths from diseases caused by air pollution from cooking (NewClimate Institute & EED Advisory, 2021). While clean cooking isn’t specifically prioritised as a mitigation action in the NCCAP, the plan acknowledges that improving biomass cooking efficiency is an important measure to reach the recommended emission reduction target for the energy demand sector (Government of Kenya, 2018).

The 2019 Energy Act puts responsibility on the Ministry of Energy to continue implementing Minimum Energy Performance Standards for appliances and devices and to integrate energy efficiency requirements into building codes (EPRA, 2019b).

Building codes in Kenya are now transitioning to European construction guidelines (Eurocodes). The code specifies that buildings must consider energy efficiency, passive and natural cooling methods, and the use of natural daylight. New housing developments should have solar hot water in bathrooms and to consider PV and wind as energy sources (C2E2, 2018).

Kenya's National Energy Efficiency and Conservation Strategy aims to develop Minimum Energy Performance Standards for more product categories, including cookstoves. While not implemented yet, the government aims to ban the least efficient products (e.g. bottom 10% in each category) from the market. The strategy also aims to develop Minimum Energy Performance Standards for new buildings and adopt a nationwide program for retrofitting existing buildings with energy efficiency upgrades (Ministry of Energy, 2020).

The Draft Energy (Management) Regulations 2020 builds on the requirements laid out by the 2012 iteration of the regulations. All facilities whose energy consumption exceeds 180,000 kWh per year are required to develop an energy management policy, perform an energy audit every four years, submit an energy investment plan that implements at least 50% of the energy savings measures identified in the audit, and designate an energy manager who is responsible for executing energy efficiency and conservation programmes (EPRA, 2020).

While the buildings sector as a whole is not outlined in the NCCAP, it is an important component of reaching Kenya’s mitigation targets related to energy demand and energy efficiency.

Agriculture

Agriculture is the largest source of Kenya’s emissions and accounted for 50% of its total GHG emissions (excl. LULUCF) in 2019 (Gütschow et al., 2021).

A sound agriculture sector is a priority of the Kenyan government because of its importance for food security, rural livelihoods and poverty alleviation. Agriculture is the most important sector for Kenya’s economy, directly accounting for 23% of the GDP or over 50% when considering indirect linkages, and 54% of employment in 2020 (Statista, 2021, 2022).

The main policy goals of the sector, comprised under the Agriculture Sector Development Strategy 2010-2020 and the Kenyan Climate Smart Agriculture Strategy (CSA) 2016-2027, are related to increasing agricultural productivity and production and promoting commercialisation as well as promoting sustainable land and natural resource management (FAPDA, 2013; Ministry of Agriculture, 2018).

The CSA Strategy is considered a tool to implement sectoral activities in contribution to Kenya’s NDC (Ministry of Agriculture, 2018). It aims to enable adaption to climate change, build the resilience of agricultural systems for enhanced food and nutritional security and improved livelihoods, and at the same time minimise emissions. The Strategy formulates the goal of reducing sectoral emissions to 32.2 MtCO2e in 2026 relative to 39.8 MtCO2e in the BAU scenario in the same year (conditional to domestic and international support) (Ministry of Agriculture, 2018). Since the strategy was adopted, agriculture emissions have continued to increase, reaching 40 MtCO2e in 2019 (Gütschow et al., 2021).

The priority mitigation actions for the agriculture sector are agroforestry (with an abatement potential of 3.99 MtCO2e by 2030), increased farm area under sustainable land management (0.83 MtCO2e) and the implementation of Kenya’s Dairy NAMA via increased productivity (0.74 MtCO2e) (Government of Kenya, 2018). Agroforestry has by far the highest abatement potential and can be considered the interface between agriculture and forestry and encompasses mixed land-use practices. It is distinct from forestry mitigation actions as it targets lands that are currently in use for agriculture. This mitigation action encourages compliance with the Agricultural Farm Forestry Rules that require every land holder to maintain a compulsory farm tree cover of at least 10% on any agricultural land holdings (Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, 2017b).

All mitigation actions together have an abatement potential of 5.56 MtCO2e by 2030, compared to the sector’s target of reducing 3 MtCO2e by 2030 (Government of Kenya, 2018; Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, 2017b).

The implementation of climate-smart agriculture practices has had mixed results. As of June 2020, 52,075 ha of degraded land has been reclaimed via sustainable land management practices, meeting 87% of the NCCAP’s 2022 target. Only 10,286 ha of agricultural land, or 4% of the 2022 target, has been put under soil nutrient management while 20,050 ha of land, or 8% of the 2022 target has begun applying conservation agriculture practices (Ministry of Environment and Forestry, 2021a).

According to the NDC baseline, absolute emissions from the agriculture sector are projected to grow from 34 MtCO2e in 2015 to 41.6 MtCO2e in 2030 while the contribution of agricultural emissions to total national emissions is expected to decrease from 59% in 2015 to 32% in 2030 (excl. LULUCF) (Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, 2017a). With implementation of the CSA strategy, absolute emissions would reach 31.6 MtCO2e in 2030 (Republic of Kenya, 2018).

If the sector successfully implements the measures from the NCCAP 2018-2022 and the sector’s CSA Strategy, it is likely that the sectoral target can be met.

Forestry

Kenya’s emissions from Land-use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF) have contributed to almost one third of the country’s total emissions on average over the last 20 years. The major reasons for deforestation are the conversion of forest land to agriculture, unsustainable utilisation of forest products (including charcoal), forest fires and shifting cultivation.

Considerable deforestation has occurred in Kenya over the last 20 to 30 years, though there is high uncertainty regarding the exact forest coverage in the country and the rates of deforestation. Between 1990 and 2000, forest land in Kenya decreased by 27% from 4,724,000 ha to 3,437,000 ha; though it had increased again to 4,037,000 ha in 2010 (FAO, 2015).

In 2020, Kenya lost approximately 17,200 ha of natural forest (Global Forest Watch, 2022), caused largely by the conversion of forest land to agriculture, unsustainable utilisation of forest products (including charcoal), forest fires and shifting cultivation (Gichu & Chapman, 2014).

Kenya’s LULUCF target is put at risk by the introduction of the Forest Conservation and Management (Amendment) Bill 2021. The bill seeks to delete a clause from the 2016 act that mandates authorities to veto anyone attempting to alter forest boundaries and forest activities that would put threatened species at risk. The amendment would weaken the role of the Kenya Forest Service and opens the door for deforestation and allocation to the private sector for development (Muiruri, 2022; Republic of Kenya, 2021b).

Sustainable and productive management of land and land resources is enshrined in the country’s Constitution, adopted in 2010, which establishes a tree cover target of at least 10% of the country’s land area. In 2017, tree cover was estimated to be 7% of Kenya’s land area (Kimanzi, 2017). The Constitution further states that land in Kenya shall be held, used and managed in a manner that is equitable, efficient, productive and sustainable, and entrenches sound conservation and protection of ecologically sensitive areas (National Council, 2010).

The Forest Conservation and Management Act 2016 provides guidance for the development and sustainable management of all forest resources. The Act classifies forests as public, community or private forests. Public forests are vested in the Kenya Forest Service (KFS), community forests are vested in the community, and each County Government is responsible for the protection and management of forests and woodlands under its jurisdiction (Republic of Kenya, 2016a).

The Act also indicates that indigenous forests and woodlands are to be managed on a sustainable basis for, inter alia, carbon sequestration.

According to the NDC baseline, the LULUCF sector is the second largest contributor to Kenya’s GHG emissions after agriculture, largely as a result of deforestation. Absolute emissions from the LULUCF sector are projected to decrease from 26 MtCO2e in 2015 to 22 MtCO2e in 2030 and the contribution of this sector to total national emissions is expected to drop from 31% in 2015 to 14% in 2030 under BAU (Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, 2017a).

In the NDC Sectoral Analysis, the forestry sector’s target is to reduce emissions by 20.1 MtCO2e below BAU by 2030, corresponding to 47% of the overall abatement task (Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, 2017b). However, Kenya’s updated NDC does not specify a sectoral target for the LULUCF sector (Ministry of Environment and Forestry, 2020).

In the NCCAP 2018-2022, the priority mitigation actions for the LULUCF sector are the restoration of forests on degraded lands (with a total abatement potential of 14 MtCO2e by 2030), afforestation and agroforestry (4.8 MtCO2e) and reducing deforestation and forest degradation by the rehabilitation and protection of natural forests (2 MtCO2e) (Government of Kenya, 2018). All mitigation options together have an abatement potential of 20.8 MtCO2e.

The NCCAP 2018-2022 proposes to restore around 40,000 ha of land per year, resulting in a total of 480,000 ha to be restored by 2030. This is significantly less than the 1.2 million ha that was assumed in the previous NCCAP 2013-2017 (Government of Kenya, 2018). The reassessment of the number of hectares of land to be restored per year correspondingly affected the estimated abatement potential of this mitigation action, reducing it from 32.6 MtCO2e (NCCAP 2013-2017) to 14 MtCO2e (NCCAP 2018-2022) by 2030.

As of June 2020, 3,699 ha of land were afforested or reforested, including agroforestry, which is far from the NCCAP target of 100,000 ha by 2022. This has been attributed to financial constraints, limited capacity, and the lack of adequate seedlings. For the other NCCAP targets, 20,121 ha of forest was put under improved management and 41,117 ha of degraded forest has been restored, both representing approximately 20% of the 2022 target (Ministry of Environment and Forestry, 2021a).

Despite the downward adjustment of abatement potential from restoration of forest on degraded lands, the abatement potential of the remaining priority mitigation actions would be sufficient to meet the sectoral target from Kenya’s original 2016 NDC, provided they are implemented.

Waste

In 2020, the waste sector accounted for 3% of Kenya’s total GHG emissions (excl. LULUCF). The need for adequate waste treatment is accentuated by the growing industrialisation of the Kenyan economy. Waste management in Kenya is regulated at the national level by the Environmental Management and Co-ordination (Waste Management) Regulations 2006 (Republic of Kenya, 2006). The regulations stipulate measures and standards that counties are to comply with in managing waste.

In February 2021, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry introduced the Sustainable Waste Management Act. While there is no mention of GHG emissions reduction measures, the bill would establish take back schemes, extended producer responsibility, and materials recovery facilities. It would also close open dumpsites and introduce sorting receptacles for organic, plastic, and general waste so that it can be eventually composted or recycled (Ministry of Environment and Forestry, 2021b).

In March 2017, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry introduced a ban on the manufacture, use and importation of plastic bags use for commercial and household packaging. Waste produces GHG emissions mainly through the processes of disposal, treatment, recycling and incineration (Government of Kenya, 2018; Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, 2017b).

According to the NCCAP 2018-2022, there is only one mitigation action for the waste sector which is related to the ongoing Solid Waste NAMA concerning the creation of recycling points and composting facilities and landfill gas capture and its utilisation for energy. The NAMA has a goal of 30% waste recovery and 70% controlled dumping by 2022, with an abatement potential of 0.49 MtCO2e (Government of Kenya, 2018).

According to Kenya’s NDC baseline, absolute emissions from the waste sector are projected to grow from 2.6 MtCO2e in 2015 to 5.2 MtCO2e in 2030 while their contribution to total national emissions is expected to remain at 4% (excl. LULUCF) (Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, 2017a). Under the lower bound of the current policy projection, absolute emissions in the waste sector are projected to grow to 5.1 MtCO2e in 2030 (Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, 2017a).

With the priority mitigation option fully implemented, the waste sector would be able to deliver 0.49 MtCO2e by 2030 and meet its 2030 sectoral emissions reduction target, outlined in the NDC Sectoral Analysis Report 2017, of reducing emissions by 0.4 MtCO2e (Government of Kenya, 2018; Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, 2017b).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter