Country summary

Assessment

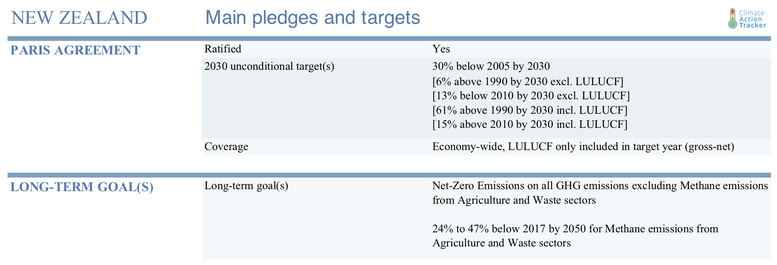

New Zealand is one of the few countries to have a zero emissions goal enshrined in law, its Zero Carbon Act, but short-term policies cannot yet keep up with that ambition. Noteworthy is the fact that the 2030 greenhouse target was not updated in the newly-submitted NDC; only a hint was included that this could happen in 2021. Methane from agriculture and waste (over 40% of New Zealand's emissions) is exempt from the zero emissions goal, and has a separate target not yet covered with significant policies. The government’s economic stimulus to recover from the lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic includes elements that could - but do not have to - prevent support for emission intensive projects. CAT rates the 2030 target as “insufficient”. It now may be met under pessimistic economic assumptions.

We expect that GHG emissions in 2020 will be 12% to 22% lower than 2019. New Zealand experienced a brief period of lockdown which is projected to shrink GDP in 2020 by between 7.2 and 34 percent and reduce activity in emissions-intensive sectors, particularly transport.

New Zealand’s rapid response to COVID-19 has helped the country deal with the health and economic crisis. Some stimulus funds have addressed both the COVID-19 crisis in tandem with the climate crisis, through environmental projects. The government’s committed NZ$20 billion funds for economic stimulus offer an unprecedented opportunity to kickstart New Zealand’s pathway to net zero emissions. New legislation for fast-tracking projects to boost employment and economic recovery have optional environmental safeguards, these safeguards need to ensure emissions-intensive projects are not approved.

The adoption of the Zero Carbon Act in 2019 was a step forward, but implementation is key and the methane exemption weakens the target considerably. The Act aims to achieve net zero emissions of all greenhouse gases, except for methane emissions from agriculture and waste, by 2050. Methane emissions from these two sectors represent over 40% of New Zealand’s current emissions. They are covered by a separate target of at least 24-47% reduction below 2017 levels by 2050, with an interim target of 10% reduction by 2030., The lion’s share of these methane emissions is from agriculture. A true commitment to net-zero would require a further reduction of 18-25 MtCO2e in 2050, corresponding to the residual methane emissions that would remain unmitigated by the 2050 target. These would need to be achieved in other sectors, in particular through full decarbonisation of energy and industry emissions by 2050.

New Zealand lacks strong policies, despite its Zero Carbon Act. The Act does not introduce any policies to actually cut emissions but rather sets a framework. The Zero Carbon Act established an independent Climate Change Commission to oversee a five-year carbon budgeting process to drive the required emission reductions.

In June 2020, the government reformed the Emissions Trading Scheme, continuing to exempt the country’s largest greenhouse gas sector emitter – agriculture - from a price on its emissions until 2025, when it was originally proposed to cover all sectors. The amendment sets a cap on emissions that can be traded, which will decrease from 2021. The reform phases out free industrial allocations of carbon units, and lifts the cap on the price of carbon from NZ$25 (US$17) to NZ$35 (US$23) per New Zealand unit (equal to one tonne of CO2 equivalent).

New Zealand has a renewable electricity target of 90% by 2025 and 100% by 2035. The government plans to develop policies to support a Renewable Energy Strategy work programme to meet these targets. The government has sought consultation for a national hydrogen strategy, with a vision paper in support of opportunities for domestic use and export of green hydrogen.

The CAT’s New Zealand emissions projections for 2030 are 8% to 17% lower compared to CAT’s previous projections in December 2019, and the 2020 projections are 14% to 23% lower. This difference in projections account for the impact of the pandemic on emissions and changes to government policy projections. The projected drop in emissions brings New Zealand closer to meeting its 2020 target, and within range of meeting the 2030 target. However, the COVID-19 impact is not a sustained reduction in GHG emissions and as the economy recovers emissions are expected to increase in 2021/22 if there is no strong push for a green recovery shifting investments towards lower carbon projects.

The CAT rates the 2030 target as “insufficient”. Under current policy projections, New Zealand may meet its “insufficient” 2030 target under pessimistic economic assumptions due to COVID-19. The updated NDC of April 2020 does not change this target. The government has, instead, stated that it has requested the Climate Change Commission to provide advice on whether and how the NDC should be changed to make it consistent with 1.5°C. This advice is expected in early 2021, but there is no commitment from the government to accept it.

To reach its net zero target for 2050, New Zealand plans to use the land use, land use change, and forestry (LULUCF) sector as an emissions sink, utilise carbon market mechanisms and exempt methane emissions (with a separate methane target).

Alongside the development of the Zero Carbon Act, the government established the New Zealand Green Investment Finance Ltd. The purpose of the institution is to catalyse investment in low-emissions initiatives, but has no investments announced yet.

New Zealand’s main instrument to reduce greenhouse gas emissions is an emissions trading scheme (NZ-ETS). The government passed major reforms to the ETS in June 2020. Despite an election pledge and coalition agreement to bring agriculture into the ETS, emissions from the sector will not be included until 2025, and farmers will be exempt from 95% of emissions charges, i.e. they will be required to meet the costs of only 5% of their emissions. This is a major backdown, as agricultural emissions represented 48% of the country’s GHG emissions excluding LULUCF in 2018, thus leaving it up to the rest of the economy to meet the target.

Amendments to the NZ ETS include introducing a cap while previously there was no emissions limit for emitters. The cap is reduced annually restricting the amount of carbon units that can be traded. It also lifted the cap on the price of carbon from NZ$25 a tonne to NZ$35 a tonne.

After agriculture, transport is the second largest source of emissions in New Zealand. The nation has one of the oldest passenger vehicle fleets in the developed world and no emissions standards. In August 2019, in response to the Productivity Commission report, the Government announced its Climate Action Plan which included a backdown on its announced pledge to make its own vehicle fleet fully electric by 2025. The Government now aims that all new vehicles entering the Government fleet are fully electric by mid-2025. The government released a draft national rail plan, which was open for public feedback earlier this year. The budget for 2020 (termed “Budget 2020”) allocated the majority of transport funds towards rail, but this allocation was far smaller than the New Zealand Upgrade Programme with huge sums earmarked for road infrastructure.

The government aims to achieve 90% renewable energy by 2025 and 100% by 2035. Currently, there are very few policies in place to meet these targets, but there are plans for a Renewable Energy Strategy work programme. In addition, the government plans to revise the National Policy Statement for Renewable Energy Generation (NPS-REG) and is considering the development of National Environmental Standards on renewable energy. The government sought consultation in 2019 on developing a national hydrogen strategy, with a vision paper in support of opportunities for domestic use and export of green hydrogen. Green hydrogen can assist in decarbonisation in a number of ways, particularly with respect to the industry sector.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter