Pledges And Targets

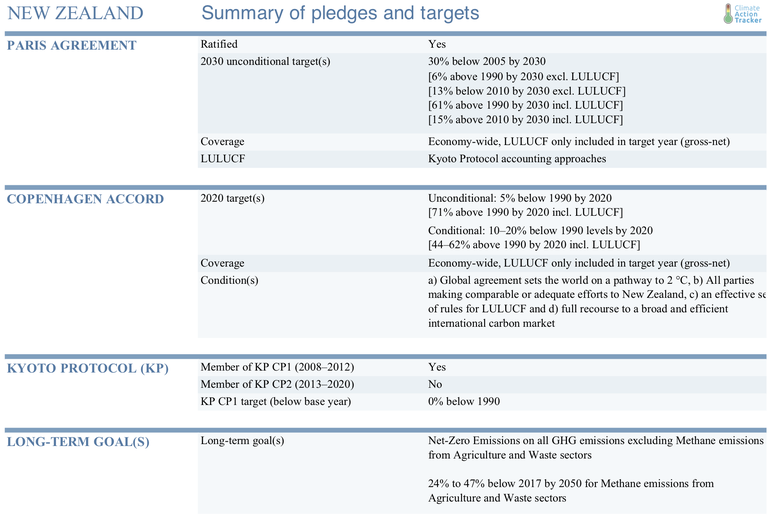

Summary table

2020 Pledge and Kyoto target

New Zealand's Kyoto Protocol target for the first commitment period (CP1) (2008–2012) was to return its GHG emissions excl. LULUCF to 1990 levels (QELRO of 100% of 1990 emissions).

Under the Kyoto Protocol accounting rules applicable to New Zealand in CP1, certain land-use change and forestry activities provided credits that were added to allowed GHG emissions, excl. LULUCF, to rise during this commitment period. In CP1, these activities resulted in extra emission allowances for New Zealand of, on average, 14 MtCO2e per year (equivalent to about 23% of base year emissions in 1990). As a consequence of its large volume of LULUCF credits, New Zealand had a substantial surplus of unused emission units at the end of CP1. In addition to LULUCF credits, New Zealand used a large amount of Emissions Reduction Units (ERUs). There have been concerns over the environmental integrity of the units purchased to meet a significant part of its CP1 target (Sustainability Council of New Zealand, 2014).

As explained below, New Zealand proposed to use these surplus emission allowances from CP1, which are derived in part from Kyoto LULUCF credits and acquired emission units from other countries, to meet its 2020 reduction target under the Convention.

In 2013 New Zealand put forward an unconditional pledge to reduce GHG emissions excluding LULUCF by 5% below 1990 levels by 2020. This pledge is complemented by an earlier conditional pledge from 2009 to reduce emissions 10–20% below 1990 levels by 2020 (Government of New Zealand, 2013). The government provided further details, including its plans to apply Kyoto-type accounting rules governing the second commitment period (2013–2020) (Ministry for the Environment, 2016).

New Zealand’s unusual decision to adhere to the Kyoto rules and subsequently ratifying the Doha amendments without signing up to the CP2 raises a number of legal issues, as the Protocol provides certain benefits only to Parties that have emission reduction commitments for CP2.1

Its 2020 net position update shows that New Zealand is projected to meet its unconditional target to reduce emissions to 5% below 1990 levels by 2020 (calculated as a budget for 2013-2020), through 108 million units from forestry activities and making use of 14.6 million available units from CP1 (out of a total surplus of 123.7 million units), where one unit represents one tonne of greenhouse gas emissions as carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e) (Ministry for the Environment, 2020a).

The New Zealand net position 2020 update translates the target into an emissions budget for the 2013-2030 period of 64 MtCO2e average annual emissions (Ministry for the Environment, 2020a). The CAT calculates the 2020 target (5% reduction compared to 1990 levels) to be 60 MtCO2e (excluding LULUCF) based on the latest historical data provided by the government (Ministry for the Environment, 2020b). For comparison, the conditional 10% and 20% targets are estimated to be 57 to 51 MtCO2e, respectively.

Using current policy projections, the CAT calculates New Zealand does not need to use the planned CP1 surplus (14.6 million units). According to historical and projected emissions for 2013-2020 (including the impact of COVID-19), New Zealand may meet its 2013-2020 emissions budget. Current projections indicate New Zealand needs to abate up to 3 MtCO2e or may overachieve the budget by 5 MtCO2e.

1 | The Kyoto rules New Zealand seeks to apply, broadly relate to: (i) The carry over of surplus emission units and allowances from the first commitment period; (ii) The ability to generate LULUCF credits during the CP2 period; (iii) The ability to purchase and sell Kyoto emission units from other Kyoto Parties during CP2; and (iv) Provisions relating to the carryover of any surplus from earlier commitment periods to the post-2020 period.

Paris Agreement targets

New Zealand’s NDC contains an emissions reduction target of 30% reduction below 2005 levels by 2030 (New Zealand Government, 2016a). In April 2020, New Zealand submitted an updated NDC (New Zealand Government, 2020). The submission did not contain a stronger 2030 economy-wide target. The updated NDC references the country’s 2050 net zero target adopted in 2019 and the establishment of a Climate Change Commission. It confirms that it has requested the Commission to provide advice and recommendations “in early 2021” on whether and how the NDC target should be updated to make it consistent with the Paris Agreement 1.5°C temperature limit. However, there is no commitment to updating the NDC.

The CAT rates the current NDC target as “insufficient”. While the net zero target and the review of the NDC target are a step forward, New Zealand needs to strengthen its 2030 target and adopt policies and measures needed to put its emissions reductions on track to meet a strengthened target. We estimate that the emission level excluding LULUCF targeted by the NDC is 67 MtCO2e in 2030.

Failure to submit a stronger 2030 target contravenes the Paris Agreement’s requirement that each NDC should represent a progression on the previous submission as stated in the Paris Agreement Decision1/CP.21 (UNFCCC, 2015). New Zealand still has time to resubmit a stronger NDC in 2020 to honour this historic year for the environmental movement, and to put the country on a trajectory to limit global warming to 1.5°C.

The NDC target falls within the current policy projections range (including the impact of COVID-19), indicating New Zealand could meet its 2030 target (see assumptions section for projection details). The current policy projections for 2030 are between 65 to 72 MtCO2e (excl. LULUCF) (compared to the 67 MtCO2e NDC target). Similarly, the target falls within the planned policy projections range of 64 to 71 MtCO2e (excl. LULUCF). New Zealand will possibly overachieve its insufficient NDC target.

Considering the target is rated “insufficient,” New Zealand should scale up its target and climate policy, as the current target is not ambitious based on current policy effort.

New Zealand’s LULUCF accounting uses a gross-net approach. The target for a 30% reduction below 2005 levels is equivalent to a reduction of 11% from 1990 levels, confirmed in the Fourth Biennial Report (Ministry for the Environment, 2019b). The Report shows that New Zealand is planning to exclude LULUCF emissions in the base year but account for them in the target year (see assumptions section). The use of this “gross net” approach raises many questions in terms of the environmental integrity of the target (Rocha et al., 2015).

The New Zealand Government plans to meet its NDC target through a combination of domestic emissions reductions, use of market mechanisms, and removal of carbon dioxide by forests (Ministry for the Environment, 2019b). Recent legislation reforms have ruled out using emissions carryover to meet the NDC (Climate Change Response (Emissions Trading Reform) Amendment Act 2020 No 22, Public Act , 2020).

We have further analysed the implications of New Zealand seeking to continue to apply a Kyoto-type accounting system as described in the NDC (New Zealand Government, 2016a), despite having not signed up to the second commitment period (CP2). For a more detailed description of the methodology and assumptions used in previous reports to estimate the potential impacts of a Kyoto-type accounting system for New Zealand’s NDC target see our 2015 country report (Rocha et al., 2015).

Long-term goal

The Zero Carbon Act adopted in 2019 is a legislated commitment to meet the “net-zero” 2050 target and provides a framework to develop policies consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels (Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act 2019 No 61, 2019). The Act sets a target to achieve net zero emissions of all greenhouse gases, except for methane emissions from agriculture and waste (which it terms ‘biogenic methane’) by 2050. These methane emissions represent over 40% of New Zealand’s emissions today (excluding LULUCF) and will be reduced by at least 24-47% below 2017 levels by 2050 as set out in the Act (Ministry for the Environment, 2020b).

The independent Climate Change Commission, established under the Act, will advise on five-yearly carbon budgets, future revisions of the 2050 target and the use of international credits. The Act allows the government to use international market credits; however, only as a last resort. The Commission has been tasked with setting a limit on emission reduction credits that can be purchased from overseas mitigation actions.

The CAT estimates the 2050 target translates to emissions levels of between 49 and 68 MtCO2e in 2050 excluding LULUCF, and net emissions (with LULUCF) between 18 and 25 MtCO2e. CAT’s current policy calculations based on government projections show that 2050 emissions will be 56 to 63 MtCO2e (excl. LULUCF). Depending on the extent of uncertain LULUCF removals, New Zealand could reach the 2050 target without any additional effort. The 2050 target is not truly net zero as it does not include methane emissions. A true commitment to net-zero would require a further reduction of 18-25 MtCO2e (i.e. the 24-47% residual methane emissions that would remain unmitigated by the 2050 target) including full decarbonisation of energy and industry emissions by 2050.

However, similar to the 2020 and 2030 targets, uncertainty is added by the accounting approaches suggested by New Zealand for the achievement of this target. The new Act states that “Emissions budgets must be met, as far as possible, through domestic emissions reductions and domestic removals.” And that “offshore mitigation may be used if there has been a significant change of circumstance” (Ministry for the Environment, 2020b).

Previous analysis found that a net zero target for all domestic GHG emissions in 2050 could be consistent with the Paris Agreement (Hare et al., 2018). An overwhelming majority of the 15,000 submissions received (91%) during the consultation process for this act supported achieving net zero emissions for all greenhouse gases (Ministry for the Environment, 2018).

The New Zealand Productivity Commission developed a number of scenarios to show net zero by 2050 is possible, and the least cost transition involves a policy driven approach (New Zealand Productivity Commission, 2018). The Productivity Commission has undertaken modelling (including methane emissions) to examine pathways from current levels to two alternative long-term targets: a 60% reduction from 1990 levels around 26 MtCO2e including a LULUCF sink over 20 MtCO2e, and a more ambitious target of net-zero emissions by 2050 with a LULUCF sink of over 40 MtCO2e. The main conclusion of the modelling exercise is that under all scenarios modelled both targets are feasible, but immediate action is needed (Productivity Commission, 2018).

The findings of the Productivity Commission confirm previous results by other modelling groups that conclude that in order to be on a trajectory toward emission-neutrality around mid-century, substantial strengthened action in the agriculture and forestry sectors (including methane emissions) is needed in addition to efforts to decarbonise the energy system further (Vivid Economics, 2017).

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter