Targets

Paris Agreement targets

NOTE: Our assessment of New Zealand's NDC update is here.

NDC description

New Zealand’s NDC contains an emissions reduction target of 30% reduction below 2005 levels by 2030 (New Zealand Government, 2016). We estimate that the emissions level excluding LULUCF targeted by the NDC is 68 MtCO2e in 2030.

In April 2020, New Zealand submitted an updated NDC (New Zealand Government, 2020b). The submission did not contain a stronger 2030 economy-wide target. The updated NDC references the country’s 2050 net zero target adopted in 2019, and the establishment of a Climate Change Commission. Further details on the April 2020 NDC submission can be found on the CAT Climate Target Update Tracker page.

The Paris Agreement requires each NDC to represent a progression on the previous submission as stated in the Paris Agreement Decision 1/CP.21 (UNFCCC, 2015). New Zealand still has time to resubmit a stronger NDC before COP26 to honour this historic occasion for the environmental movement, and to put the country on a trajectory to limit global warming to 1.5°C. The government has stated it plans to do so.

The NDC - and the CCC - makes a logical error by using the gross - net approach for its emissions projections. New Zealand excludes LULUCF emissions in the base year (2005) but accounts for them in the target year (2030) (see assumptions section). The use of this “gross net” approach raises many questions in terms of the environmental integrity of the target (Rocha et al., 2015). This flawed approach results in a system that allows net emissions to continue to increase. Under the present NDC construction, the country's net emissions could be 4% above 2005 levels in 2030, and more than 44% above 1990 net emissions.

Lawyers for Climate Action NZ Incorporated (LCANZI) is a not-for-profit group consisting of lawyers supporting climate action. LCANZI finds the current accounting method is not 1.5°C compatible as required by law in the Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act 2019, as legally the NDC needs to take into account net figures to account for carbon removals from forestry and compare “apples to apples” (LCANZI, 2021a).

The claim is supported by a coordinating lead author of the section relating to emissions reduction pathways compatible with 1.5°C of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) who finds that the CCC budget is not compatible (Daalder, 2021). The Ministry for the Environment and Statistics NZ use the same methodology as they do to calculate emissions required for a 1.5°C pathway for 2030 and 2050 following a net emissions approach rather than gross emissions (LCANZI, 2021a).

The New Zealand Government plans to meet its NDC target through a combination of domestic emissions reductions, use of market mechanisms, and removal of carbon dioxide by forests (Ministry for the Environment, 2019). Legislation reforms have ruled out using emissions carryover to meet the NDC (New Zealand Government, 2020a).

We have further analysed the implications of New Zealand seeking to continue to apply a Kyoto-type accounting system as described in the NDC (New Zealand Government, 2016), despite having not signed up to the second commitment period (CP2). For a more detailed description of the methodology and assumptions used in previous reports to estimate the potential impacts of a Kyoto-type accounting system for New Zealand’s NDC target see our 2015 country report (Rocha et al., 2015).

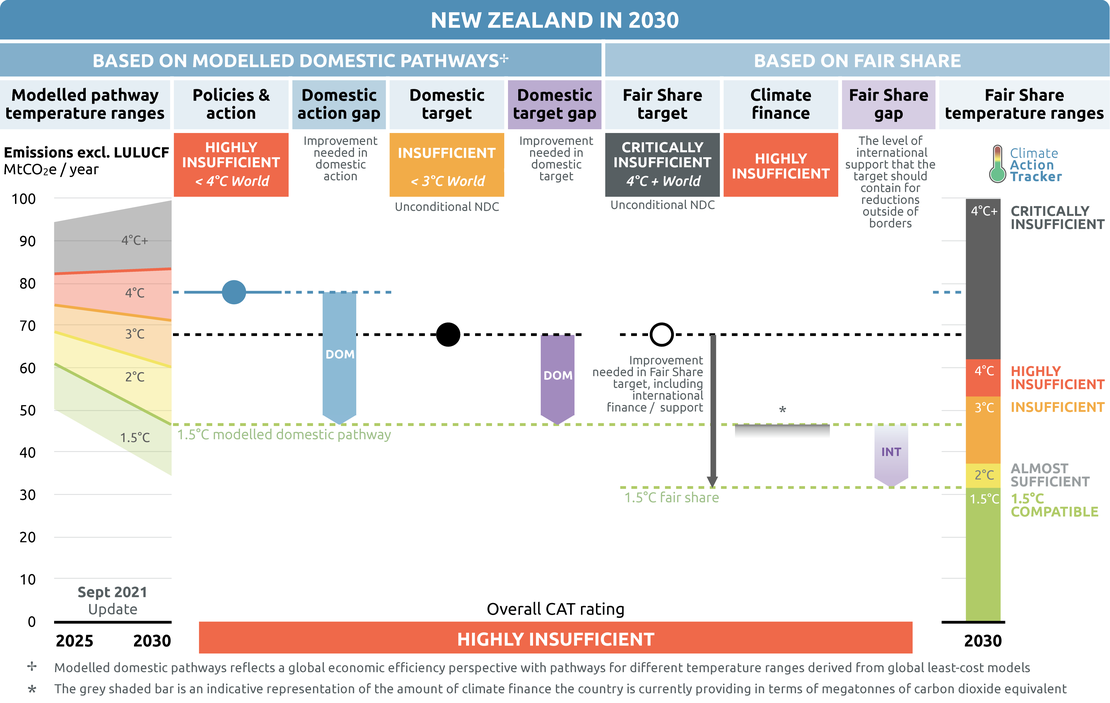

The CAT rates New Zealand's target as "Insufficient" when rated against modelled domestic pathways ("domestic target"), and "Critically insufficient" when rated against the fair share emissions allocation ("fair share target"). New Zealand does not specify an international element in its NDC, so we rate its NDC target against the two rating frameworks.

The “Insufficient” rating indicates that New Zealand’s domestic target in 2030 needs substantial improvement to be consistent with the 1.5°C temperature limit. The Climate Change Commission (CCC) advice to government in June 2021 draws a similar conclusion.

The CCC recommends the NDC should be “much more than 36%” (including LULUCF) but failed to recommend a specific number (Climate Change Commission, 2021a). The CAT calculates the 1.5°C domestic emissions pathway for New Zealand is 44% below 2005 emissions in 2030 (excluding LULUCF).

The NDC is equivalent to 67 MtCO2e whereas a 1.5°C domestic emissions pathway (least cost modelled pathway) is 32% lower in 2030 at 46 MtCO2e (excluding LULUCF). If all countries were to follow New Zealand’s approach, warming would reach over 2°C and up to 3°C. To be 1.5°C compatible, New Zealand needs to strengthen its 2030 target and adopt policies and measures that ensure that their emissions reductions meet such a target. Critically, all sectors, including agriculture, should be included in any target update.

We rate New Zealand’s target as “Critically insufficient” when compared with its fair-share emissions allocation. The “Critically insufficient” rating indicates that New Zealand’s fair share target in 2030 reflects minimal to no action and is not at all consistent with the 1.5°C temperature limit. The NDC target is not in line with any interpretation of a fair approach to meeting the 1.5°C limit. The target would need to be 53% lower to be a 1.5°C compatible in terms of New Zealand’s fair share. The current target is equivalent to 67 MtCO2e in 2030 where as a 1.5°C compatible fair share target would be around 32 MtCO2e. Substantial improvement is needed. Some of these improvements should be made to the domestic emissions target itself, others could come in the form of additional support for emissions reductions achieved in developing countries in the form of finance. If all countries were to follow New Zealand’s approach, warming would exceed 4°C.

The CAT’s previous rating for New Zealand was categorised as “Insufficient” which was based on the fair share target. The CAT rating methodology has changed and New Zealand is now “Critically insufficient”. The update of our fair share calculations for New Zealand causes the required fair share contribution to result in lower emissions levels, mainly because the upper bound of the fair share is more stringent under the new methodology. In addition, the temperature levels are now evaluated with a 66% chance of staying below. The fair share contribution of New Zealand is still relatively less stringent in comparison to other developed countries (e.g. Germany), because New Zealand’s historic responsibility, in terms of cumulative emissions, is not as high when compared to some other developed countries.

While New Zealand’s finance rating is poor, it is one rating level better than New Zealand’s "Critically insufficient" fair share target rating and can therefore improve the overall fair share rating. Taking both New Zealand’s emissions reduction target and climate finance into account, we rate the overall fair share contribution as “Highly insufficient”.

New Zealand’s international public climate finance contributions are rated “Highly insufficient.” The country remains committed to climate finance in the period post-2020 but contributions to date have been very low compared to its fair share. To improve its rating New Zealand needs to improve climate finance commitments and make explicit commitments to prevent investments in fossil fuel finance abroad.

Reported contributions fall short of New Zealand’s fair share contribution to the USD 100bn goal and show no clear trend of increasing. A big disbursement in 2014 distorts the trend. Annual contributions with climate as the main component have been less than a third of 2014 values – but have increased in recent years.

New Zealand expects to meet its commitment to deliver a total of NZD 300m in climate finance between 2019 and 2021, but this target is still insufficient. A clear and sustained increase in international finance contributions is fundamental in the period post-2020.

Although New Zealand does not finance fossil projects overseas, there are also no explicit commitments to refrain from doing so in the future.

In April 2021, New Zealand passed legislation which mandates climate risk reporting for banks, asset managers, and insurers, making it the first country in the world to implement such mandatory climate risk reporting. Financial institutions are required to annually report on governance, risk management as well as strategies for climate change mitigation.

Net zero and other long-term target(s)

We evaluate New Zealand' net zero target as: Poor.

New Zealand passed its Zero Carbon Act in 2019 as an amendment to the Climate Change Response Act. It sets a target for all greenhouse gases except for biogenic methane – methane from agriculture and waste – to reach net zero by 2050. There is a separate target for biogenic methane emissions to be 24-47% below 2017 levels by 2050.

The Act established an advisory body – the Climate Change Commission – that reviews and, if “significant change has occurred,” propose changes to the net zero target. Interim emissions budgets are also mandated by the Act, which must be accompanied by supporting policies and strategies that draw on the Commission’s advice. The government has set a provisional emissions budget which is subject to change. In June 2021, the CCC recommended three five-year emissions budgets to 2035 to chart New Zealand’s course to meet the 2050 targets (Climate Change Commission, 2021a). However, the CCC’s budget to 2030 has been criticised as unlawful by LCANZI as it found the budgets do not align with a 1.5°C pathway (LCANZI, 2021b).

While the legal architecture of New Zealand’s net zero target is relatively strong, it does not follow good practice on a number of elements. In addition to biogenic methane, international aviation and shipping are also outside the target’s scope, and the government reserves right to use of international offset credits to meet its net zero target in the case of “a significant change of circumstance”.

The transparency of the target is also poor, with unclear assumptions of the role of carbon dioxide removal or the land sector, and no clarity on how the government has assessed the net zero target to be a fair contribution, nor on what measures and sector-specific strategies will be used to achieve this target.

For the full analysis click here.

2020 pledge

In brief, New Zealand has an unconditional target of reducing emissions 5% below 1990 by 2020, and a conditional target of 10 to 20% below 1990 emissions levels by 2020. The CAT calculates New Zealand will not meet its 2020 pledge when excluding LULUCF. The unconditional target is calculated to be 62 MtCO2e in 2020 excluding LULUCF. The conditional target is calculated to be 52-59 MtCO2e excluding LULUCF. Emissions are estimated to be 82 MtCO2e in 2020, which is 26% above 1990 levels or 65 MtCO2e (excluding LULUCF). However, the government suggests the target will be met, a conclusion determined by a number of emissions accounting practises.

New Zealand's Kyoto Protocol target for the first commitment period (CP1) (2008–2012) was to return its GHG emissions excl. LULUCF to 1990 levels (Quantified Emission Limitation and Reduction Obligation, QELRO, of 100% of 1990 emissions).

Under the Kyoto Protocol accounting rules applicable to New Zealand in CP1, certain land-use change and forestry activities provided credits that were added to allow GHG emissions excl. LULUCF to rise during this commitment period. In CP1, these activities resulted in extra emission allowances for New Zealand of, on average, 14 MtCO2e per year (equivalent to about 23% of base year emissions in 1990).

As a consequence of its large volume of LULUCF credits, New Zealand had a substantial surplus of unused emission units at the end of CP1. In addition to LULUCF credits, New Zealand used a large amount of Emissions Reduction Units (ERUs). There have been concerns over the environmental integrity of the units purchased to meet a significant part of its CP1 target (Sustainability Council of New Zealand, 2014).

As explained below, New Zealand proposed using these surplus emission allowances from CP1, which are derived in part from Kyoto LULUCF credits and acquired emission units from other countries, to meet its 2020 reduction target under the Convention.

In 2013 New Zealand put forward an unconditional pledge to reduce GHG emissions excluding LULUCF by 5% below 1990 levels by 2020. This pledge is complemented by an earlier conditional pledge from 2009 to reduce emissions 10–20% below 1990 levels by 2020 (Government of New Zealand, 2013). The government provided further details, including its plans to apply Kyoto-type accounting rules governing the second commitment period (2013–2020) (Ministry for the Environment, 2016).

New Zealand’s unusual decision to adhere to the Kyoto rules and subsequently ratifying the Doha amendments without signing up to the CP2, raises a number of legal issues, as the Protocol provides certain benefits only to Parties that have emission reduction commitments for CP2.1

New Zealand publishes a net position update to report on progress towards the emissions reduction target for 2013 - 2020. New Zealand’s April 2021 update anticipates the unconditional target will be met. The target to reduce emissions to 5% below 1990 levels by 2020 is calculated as a budget for 2013-2020, amounting to 510 MtCO2e. To meet the 2020 target New Zealand intends to use 109.2 million units from forestry activities and 23.1 million available units from CP1 (out of a total surplus of 123.7 million units), where one unit represents one tonne of greenhouse gas emissions as carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e) (Ministry for the Environment, 2021b).

1 | The Kyoto rules New Zealand seeks to apply, broadly relate to: (i) The carry over of surplus emission units and allowances from the first commitment period; (ii) The ability to generate LULUCF credits during the CP2 period; (iii) The ability to purchase and sell Kyoto emission units from other Kyoto Parties during CP2; and (iv) Provisions relating to the carryover of any surplus from earlier commitment periods to the post-2020 period.

Further analysis

Latest publications

Stay informed

Subscribe to our newsletter